March 31, 2021

Hayley Redmond lines up her shot, squeezing one eye closed, before releasing the ball. She hits the jack square-on, despite the glare of studio lights and a camera watching her every move.

She’s used to tuning out onlookers. Their expectations, she tells us later, never really stopped her.

Redmond’s athletic feats — and her advocacy with Easter Seals, a group of charitable organizations that supports the development and advancement of persons with disabilities — have landed her on the news several times since she was young.

Born with cerebral palsy, Redmond can’t walk or run, but still managed to appear at a wide array of newsworthy events: summer camps, sailing races, accessible dodgeball games.

In 2002, on one of her first appearances on CBC News, Redmond, then 10, opened up about how athletics saved her from a lifetime of confinement to a wheelchair.

“I feel like I can do anything other children can do,” she told a reporter, just after a sailing class. Now, we’re checking back in with Redmond, 29, as part of CBC Newfoundland and Labrador’s series, This Is My Story, to see what life is like for her today.

’Our little surprise’

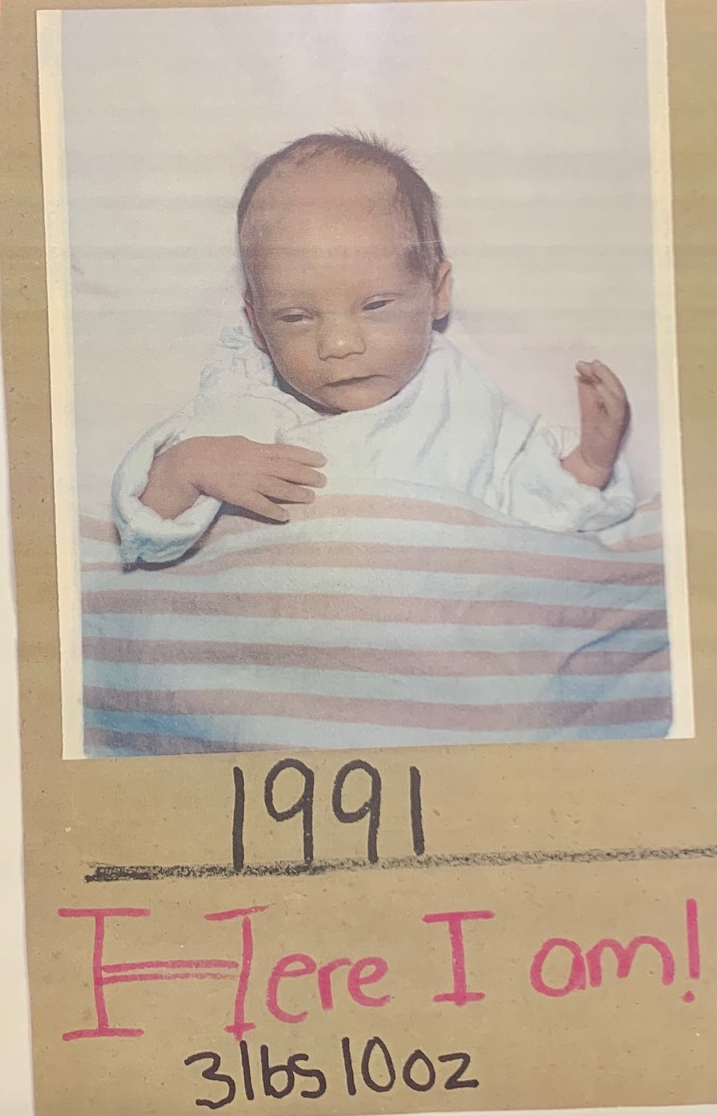

Redmond’s hurdles started early. Really early. She was born premature, and weighed only three pounds.

“That was our little surprise,” her mother, Lindsey Redmond, recalled.

At first, Hayley thrived. But as she hit the six-month mark, Lindsey noticed her daughter’s rigid muscles.

“She was very stiff,” Lindsey Redmond said. “That sometimes is common with preemies, but eventually it came to light that, yes, she did have CP.”

Abnormal brain development or damage in the womb can cause cerebral palsy. Its impact ranges from mild to severe. Hayley has the spastic quadriplegic type, which affects all four limbs, plus her fine motor skills. She uses a wheelchair to get around.

Hayley's diagnosis meant that, in those early years, she often felt left behind. Surgeries left her in lengthy recovery, and when she wasn’t convalescing or in physiotherapy, Lindsey Redmond tried everything to loosen up her daughter’s limbs, to guarantee Hayley had a full childhood.

Hayley Redmond says it wasn’t always easy. “[In elementary school, I] wasn't bullied per se, but I wasn't always included in what could be done. And I always felt like I could do anything,” she said. “Sometimes, the teacher would say, ‘No, that's not safe.’ My thought was, ‘How is it safe for the other kids, but not safe for me?’”

Her mother nods. “We had to fight just to let her participate in recess, outside with the other kids,” she said.

When Hayley was eight, she remembers her dad heading out to buy rollerblades for her two older sisters. “I wanted some too,” she recalled. “And my dad said, ‘I really don't know how that's going to happen.’”

Hayley Redmond and her mom, Lindsey Redmond, describe Hayley's journey in this video:

She tagged along anyway. "We found these rollerblades that went over my shoes, and I got in my walker and started rollerblading around the cul-de-sac where we lived," she said, grinning. "[I] turned around to my dad and said, 'See, I can do it!'"

Hayley Redmond later discovered accessible sailing and snorkeling. From there, her interests snowballed. Today, in an average week, she might find herself sharpshooting, rock-climbing, and fighting over a puck in her Saturday sledge-hockey games.

Any activity, her mom adds, helps cerebral palsy sufferers. So Hayley tried them all.

Making her mark on bowling

Not all sports are disability-friendly. Hayley Redmond learned that the hard way.

Around the same time she strapped on the rollerblades, she picked up bowling. She entered a youth tournament and won the gold medal. But not everyone was happy about that, she said.

“[Some people] didn't think that I should have won, because my dad was helping me,” Redmond explained.

Back then, bowling associations didn’t offer any options for people in wheelchairs. So Hayley Redmond and her supporters crafted their own, pitching in to develop an accessible ramp to allow her to bowl independently.

“There was a lot of controversy over that, because the equipment needed to be standardized … we had to do a fair bit of scrambling and research,” Lindsey Redmond said. “Pictures had to be sent, measurements had to be sent and [taken]. It took a fair bit of work.”

The Canadian 5 Pin Bowlers’ Association eventually approved the ramp. Now, Hayley Redmond says, anyone can use it.

“I don’t bowl anymore,” she said. “But I'm glad to have left a mark.”

A dream for the next Paralympics

These days, Hayley Redmond is busy mastering a sport designed specifically for people in wheelchairs: boccia, a cross between lawn bowling and curling. She was introduced to the sport in 2011.

“My first thought was, ‘Oh, this is like bowling, but I won't need my dad.’ It was a sport that I could be completely independent in. So I was all for that,” she said.

Hayley's team headed to the nationals in Montreal in 2013, and her mother says they took a beating. “It was an eye opener,” Lindsey Redmond said. “But you know what? We learned.”

Hayley practiced, her mom recounted, growing more competitive with each passing year.

“That's nail-biting. Any children that you have, that are in sports, [it’s] like, ‘Oh, can I watch it? Did she do OK?’ But you get past that, and then you just get out there and you... help them analyze their strong points and their weak points and work on it.”

Boccia connected Hayley Redmond to players, and now friends, in Scotland and Thailand. She’s travelled around the world to play, training hard enough — at least 12 hours on the court each week, plus swimming and core exercises — to score a spot on the national team.

She’s setting her sights on the 2024 Paralympics.

“Boccia became a major purpose for me and my life,” Redmond said, “and a reason to keep going.”

Breaking away

Hayley Redmond’s challenges, and her victories, aren’t confined to athletics.

Growing up, she depended on her parents for everything. At 15, Redmond wanted to break away, at least a little. So she booked herself a place in an Ontario summer camp.

Nine years later, she was finally able to go to the camp without her mom or dad, and live independently.

"Don't let your parents, your friends, anyone tell you you can't do it, because they’re probably wrong."

“It’s just taught me … how to survive alone,” she said. “You know, I remember having to call mom and ask, ‘What is this type of chocolate that I like?’”

She turns to her mom, smiling. “I think I called you at one point — ‘What size underwear am I?’ I didn’t even know! Because those things were done for you as someone with a disability, which is no fault of anyone else. It’s just the way it is.”

Redmond says this summer may be her last as a camper. After that, she’ll return as a counsellor with a recreation degree.

Eventually, she’s hoping that work experience will lead her to a career with Easter Seals, developing programming for the next generation of athletes.

Redmond says despite the hardships of her condition, she doesn’t long for its absence.

“I don't know any different. So it's awfully hard to imagine what life would be like without it, because I've never experienced that,” Redmond said.

“I don't think I'd be as involved in sports as I am today ... I think [cerebral palsy] gives back what you lose. It gives you lifelong friends, because you always need help in your life. You always need someone to be there for you.

“I think it makes you more of a thinker, a planner. You always try to figure things out.”

And it’s lent her words of wisdom for the children she one day hopes to teach.

“Go for it. Try it. Don't let your parents, your friends, anyone tell you you can't do it, because they’re probably wrong,” she said.

Correction

A previous version of this story incorrectly referred to Hayley's mother, Lindsey Redmond, as Gillian Batten.

This Is My Story

This Is My Story is a special series from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador, where we check back with people who have overcome some tremendous struggles in their lives.

Explore previous stories from this series: