March 3, 2021

Shane Burridge and his wife Colleen walk hand-in-hand on a trail in Portugal Cove-St. Philip’s, just outside of St. John’s. It’s a sunny, warm fall day, and the couple is beaming.

Looking at Shane now, it’s hard to believe he’s the same man who first spoke to CBC News in 2017.

Since then, Burridge says, he has lost weight, switched to a plant-based diet, and is feeling fantastic. And, the biggest development of all — he no longer has to do dialysis.

Burridge, 46, who’s originally from Elliston, on Newfoundland's Bonavista Peninsula, received a long-awaited kidney transplant about a year and a half ago.

“We're both very happy that we have a new lease on life,” he said.

Burridge is now speaking with CBC Newfoundland and Labrador as part of its series This Is My Story, where we check in with people who have gone through some trying times, and to see where they are today.

His health issues started in 2009. Burridge saw a gradual decline in his energy, and eventually he noticed inflammation and a dramatic weight loss of about 25 pounds in a matter of weeks.

“We found out it was lupus — lupus nephritis,” he recalled.

Lupus is an autoimmune disease that causes the immune system to produce proteins that attack tissues and organs. Lupus nephritis occurs when those proteins affect structures in the kidneys, which filter waste.

It causes kidney inflammation, and can lead to kidney failure.

Burridge was able to keep his symptoms at bay for four years with immunosuppressant drugs and steroids. But in February 2013, he decided it was time to start dialysis treatments at St. Clare’s Mercy Hospital in St. John’s.

“I didn't have much of a choice,” he said. “Things were looking pretty terrible at that point.”

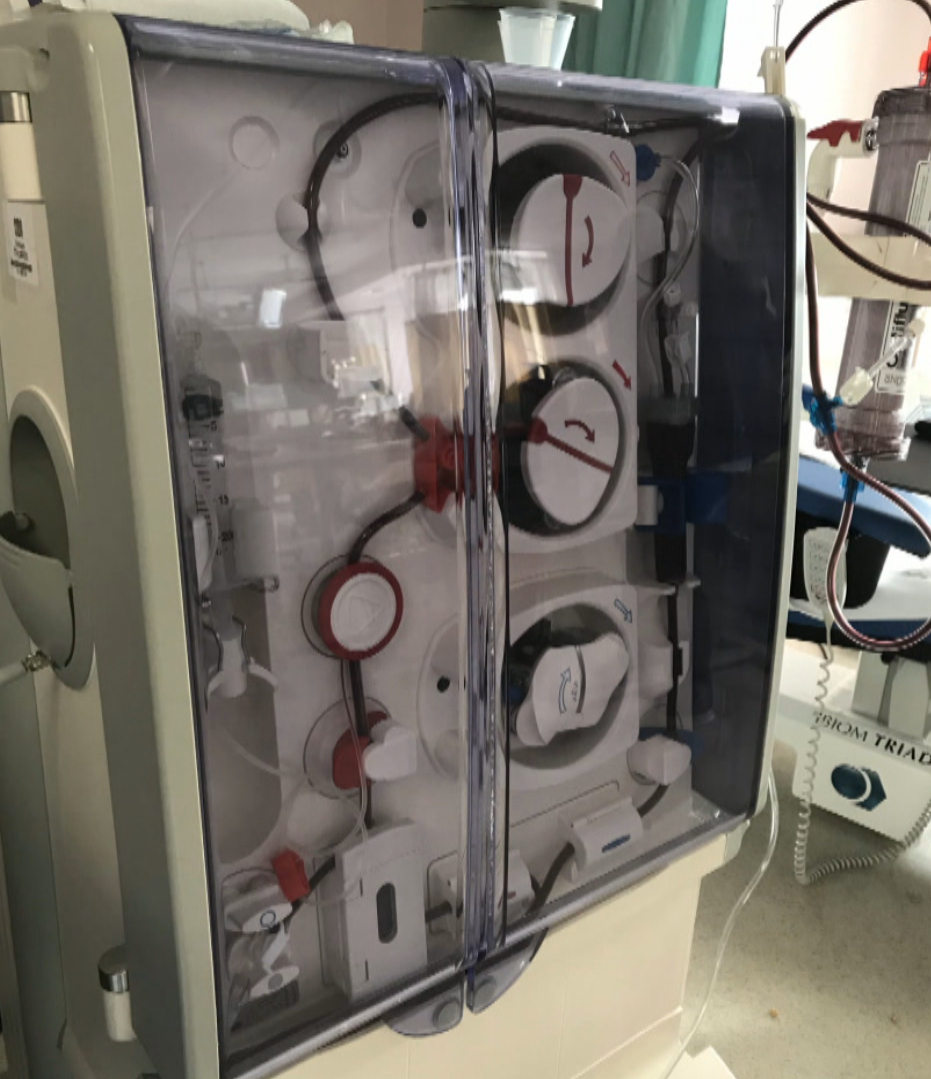

Burridge started with hemodialysis, where a machine does the work your failing kidney can’t handle anymore. His blood was pumped through a dialysis machine that removes waste and excess fluid, before returning the cleaned blood to the body.

Those treatments each lasted for about 3½ hours, three times a week.

Four months later, he switched to peritoneal dialysis — treatments where a cleansing fluid flows through a catheter, into your abdomen, to remove waste products from the blood — which he could do at home. It would take about half an hour, but had to be done four times a day.

Shane Burridge describes his journey in this video:

“Dialysis took a physical toll as well as an emotional toll,” Burridge said.

“With these … fluid changes every six hours, there's not much time for anything else, because by the time you get to go somewhere, you've got to turn around and go back, and do another change.”

Burridge did this type of dialysis for almost four years, before having to go back to his previous treatments at a clinic — which were for longer periods: more than four hours at a time, three days a week.

The call that changed his life

Time slowly ticked by while he waited for news about a new kidney.

It took Burridge four years to get on the deceased organ donor transplant list, which tracks people who agree to donate their organs or tissues at the time of their death to someone in need.

According to the Kidney Foundation of Canada, the length of time a person has to wait for a transplant is hard to predict, because it depends on how difficult it might be to find an appropriate match, and how many kidneys become available.

- 'Frustrating process': Patient says Eastern Health hampering efforts for new kidney

- RCMP officer anxiously awaiting life-altering kidney transplant

In early August 2019 — after years of waiting for a new kidney — the call finally came.

“We were at Costco, my wife and I, and it was approaching lunchtime.… [We were] going to have a few people over for a barbecue the next day,” he recalled.

“We had a cart full of items, and my phone rang.… It was the transplant co-ordinator basically saying, ‘We've got a kidney for you, and you've got to get to Halifax.’”

They abandoned their shopping cart at Costco. It was time to move.

Burridge had to do one final round of dialysis at the local clinic before heading to the airport.

Burridge checked into Victoria General Hospital in Halifax later that night, and then waited for the life-changing surgery that came the following afternoon.

“I woke up about 3½ hours later in recovery, with a new lease on life,” he said, beaming.

He wouldn’t call his family before the procedure, afraid that anything could go wrong at the last minute. But once it was a done deal, he was excited to share the news.

“I was happy. [It was] more emotional for them,” he said. “I was more focused now on, ‘OK, I got this done. Let’s see how things are.’”

Meeting Dan

Burridge wasn’t the only person at Victoria General who was getting an organ transplant that weekend.

That first night in Halifax, his wife Colleen met a woman from Moncton, N.B., in the waiting room. The two got to talking, and the woman’s last name happened to be McLaughlin — which was also Colleen’s maiden name.

But that wasn’t the only thing they had in common: the women discovered that both of their husbands were getting new kidneys.

Dan McLaughlin started doing dialysis in September 2016, and got on the transplant list around that same time.

He started with peritoneal dialysis at home, and later switched to doing it overnight.

“Just before I got my kidney, I was doing 12 hours every night — and it still wasn't enough,” McLaughlin said. “I was connected to a machine … so that meant life ended at 8:30 p.m, and started again at 8:30 a.m.”

But luckily, after three years of waiting, the call came — in similar fashion to Burridge’s. McLaughlin and his wife were preparing for a shared 60th birthday celebration.

“So Friday, around 10 a.m., we were preparing stuff for the party, which was to be on Saturday, and all of a sudden, the phone rang,” he said.

“And [the person on the other line] said, ‘You have to be in Halifax in four hours.’ And then we broke down. We were totally stunned.”

They packed up the car, and his wife started the drive to Halifax, while McLaughlin texted family and friends to say the party was off.

“Four hours later, we were at the hospital checking in.… It all happened so fast, that it’s almost like it was a dream,” he said.

“It's difficult to verbalize how you feel when something potentially life-changing is going to happen to you and you see it coming, but you don't believe it.”

McLaughlin went in for surgery the following morning.

“When I woke up, it was immediate. I took a deep breath. It felt easier to breathe. For some reason, the colours in the room seemed brighter,” he said. “I just felt more energetic immediately.… It was amazing.”

A few days after the surgery, as both men recovered, McLaughlin and Burridge finally met.

“We became friends. We’ve stayed in touch ever since,” McLaughlin said.

Discovering the donor's identity

When it comes to organ donation, McLaughlin says information about the identities of donors and recipients are often kept confidential, to protect privacy.

“We had suspicions of the donated kidney having been from somewhere close to Halifax,” he said.

After he returned home to Moncton, McLaughlin said a woman contacted him on social media, and said she believed McLaughlin had received her deceased husband’s kidney.

At the time, he decided to take a “wait and see” approach.

“Because if this person's husband was our donor, we knew that she was grieving while we were celebrating. And it would have been rather difficult to relate to each other in that way,” McLaughlin said.

Later, the transplant clinic encouraged the recipients and the donor’s family to write letters to each other.

When they received each other’s letters, and spoke once again over social media, they confirmed that Chris Williams was in fact the donor.

Williams, 40, of West Chezzetcook, N.S., was in a single-vehicle crash on July 25, 2019, and died a week later.

According to his obituary, Williams was a member of the Royal Canadian Navy and had done numerous deployments. He received a medal for earthquake relief in Haiti, the General Campaign Star, and the UN medal for his time in Libya.

The obituary noted he was also a loving husband and the father of three young children.

“His family is comforted in knowing that in this terrible loss, Chris has helped others through the donation of organs and that a piece of him lives on to the benefit of others,” the obituary reads.

Burridge says he’ll forever be grateful to Williams.

“Chris had saved my life, he saved Dan's life. And with organ donation being so important, I mean, here it is laid out, right in front of you,” he said.

“As I've learned, he saved six lives that day.… What a tremendous thing to do. And I mean, he was a hero in his regular life. And he's a hero once he succumbed to his injuries and he made the ultimate sacrifice, saving so many people.… It's incredible.”

Newfound freedom

Once Burridge started recovering from the surgery, he slowly started getting back to having a normal life.

“Excellent. Feeling excellent. Blood work is good. Kidney is functioning at normal,” he said.

Burridge says a kidney transplant is a treatment, not a cure. There are immunosuppressant drugs to ensure your body doesn’t reject the organ, and there’s regular blood work to ensure everything is working smoothly.

“But, as I say, the leash is getting a little longer, and the freedom is there,” he said.

Freedom he has not known for a very long time.

He had to take a leave of absence from the RCMP in 2018. About a year ago, he returned to the force, and has since worked himself back up to full-time hours.

Burridge now enjoys kayaking, mountain biking, going for walks and motorcycle rides, and berry-picking — “things that I hadn't done in a long, long time,” he said.

“It's funny to get up in the morning and not be tired. And to go out and say … ‘OK, yeah, we can go out for dinner. Yeah, we can do this now, we can do that,’” he said. “And to go home without planning dialysis in Bonavista, or taking a truckload of equipment with you … it's unreal.”

Once the pandemic ends, Burridge says, he and his wife plan to travel more.

“There's a few places on our list that we want to knock off,” he said.

Looking back on his time of doing dialysis, Burridge says it’s like those difficult years didn’t exist.

“Once you get the transplant, it’s almost as if, ‘Did I do dialysis?’” he said.

“Dialysis was for six and a half years of your life, and it consumed your time. And it's unreal how with the new kidney … I don't have to get in the dialysis chair.”

Burridge has some advice for those who are still waiting patiently for that call: “Keep strong and keep yourself going, because the call will happen,” he said.

Words of thanks for Chris

When asked what he would say to his deceased donor, Chris Williams, if he had the chance, Dan McLaughlin was caught off-guard, and welled up.

“I’d say thank you, obviously. It's like a second life for me. I'm 61; I feel better now than I did at 50,” McLaughlin said.

“If I was to meet Chris, I would tell him what it's done for me and what it's done for my family. We don't worry as much.… I can travel now. I'm doing renovations around the house. I just retired. And so now, I'm looking forward to a nice, long retirement.

“My life expectancy is greatly improved, compared to what it would have been on dialysis. The quality of life is, as I said, better than I could have imagined. So I'd want him to know that.”

When asked the same question, Burridge pauses briefly.

“I would just say, 'Thank you, brother. You are truly a hero, and to make the ultimate sacrifice as you did and to save so many lives, there's a special place in heaven for you, and I hope you're sitting at the right hand side there,'” he said.

“'And I will see you and I will meet you. And I can't wait … but I got a bit of things to do first.'”

This Is My Story

This Is My Story is a special series from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador, where we check back with people who have overcome some tremendous struggles in their lives.

Explore previous stories from this series: