January 16, 2019

With help from her coach, Elaine Dodge-Lynch gets into position at the Heavyweights gym in Donovans Industrial Park to do a deadlift.

Some of her gym buddies are sitting on a nearby workout bench, cheering her on as she prepares to lift a bar that's loaded up with about 115 pounds of weights.

Weightlifting is a challenge — but for Dodge-Lynch, it's even more so.

Four years ago, the Paradise woman lost her fingers and toes when she suddenly became very unwell, very quickly. Her unusual case attracted the CBC’s attention. As part of a new series — This Is My Story — we revisited Dodge-Lynch to see how her life has changed.

She has more to contend with than just the weight on the bar.

First, Dodge-Lynch had to find equipment to help her to be able to do it.

Since there aren't many customized devices on the market, Dodge-Lynch says, her coach had to get a few things together: a dip belt and TRX straps.

"It enabled us [to] take my hands out of the equation," she said.

"I do have straps with hooks that I use [but] there's a weight limit on what I can pull due to the mechanics, and it cuts off the blood supply... It's not that beneficial when I'm doing something heavier."

Watch Elaine Dodge-Lynch describe her journey:

Dodge-Lynch says she also has had to learn how to keep her balance for the different manoeuvres.

"When I do the deadlift, I have to keep myself from going forward. Same with the squat, because when you get that heavy weight on your back, if you teeter at all — you usually have your toes to save you," she said.

Her coach says Dodge-Lynch also has perfect form for her chest press. That's because she has no choice — without fingers, she can't rotate the bar forwards or backwards, so she has to balance it perfectly on her limb.

Dodge-Lynch says the training has really helped with strengthening her core.

"I've become much stronger and it's done wonders for my balance. Walking up and down my stairs, I can lift my kids... I can ride a bike. So it's helped a lot," she said.

"It's a huge benefit to my everyday life."

Dodge-Lynch says she loves pushing herself by lifting the heavier weights.

"You get a natural high when you can do things that you didn't think you could," she said.

"Especially if I have a squat bar on my back and I'm pushing weight — it's great."

But it's not just happening at the gym; Dodge-Lynch has been pushing herself endlessly since January 2015.

Losing her digits

Four years ago, Dodge-Lynch was working as a biochemist at Memorial University in St. John's when she quickly became ill, and her life changed forever.

The next day, she had a high fever, and her husband, Lloyd Lynch, brought her to emergency. She was diagnosed with influenza and sent home.

Twenty-four hours later, she was back at the hospital, and placed on a wide-spectrum antibiotic for an infection, which doctors later discovered was on one of her ovaries.

"I had to go into emergency surgery. And at this point, it looked like I may not be strong enough to survive the surgery — but if I didn't have the surgery, I wouldn't survive either," she said.

But Dodge-Lynch pulled through, and over the next few days, the medical staff discovered what had happened: a strep infection that led to toxic shock syndrome.

"I still don't know the source," she said.

She was on life support for a week in an induced coma, and later, she was on dialysis for kidney failure.

"When all this happened, I ended up with what they call gangrene," she said.

"Because of the medication they had to give me to save my vital organs, it took the blood from my extremities, and I ended up having to have four amputations."

Getting back home

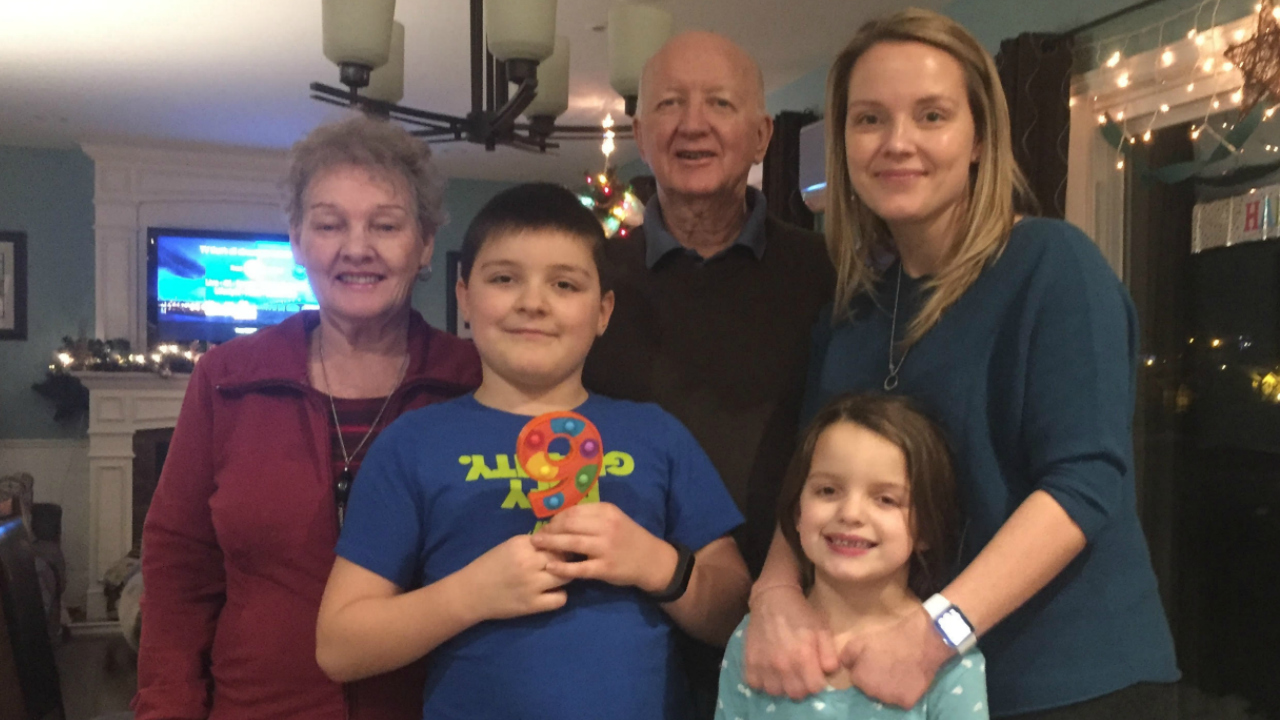

After 10 weeks at the Miller Centre in St. John's for physiotherapy and rehabilitation, Dodge-Lynch decided she had to get home to her husband, her two-year-old daughter and her six-year-old son.

She says it was a huge adjustment.

"The first thing was getting into the vehicle to come home. I could barely get into the vehicle," she said.

"I'm in a two-storey house, and I came home and my bed was upstairs... [Lloyd] had to carry me up the stairs.

"But being the type [of] person I am, that's the only time that happened."

Dodge-Lynch says at first she couldn't walk very well, or do much for herself, and she was on a lot of pain medication.

Everything was a challenge.

"I had to get someone to bag up my hands and feet to get a shower. I couldn't stand in the shower, because my balance was horrible," she said.

"My hands were super-sensitive, because when you have amputations, it's a lot of... cut nerves," she said.

"I couldn't even reach for a utensil in my drawer. It was just like reaching into a bag of nails... So I couldn't help in the kitchen."

Everyday things you take for granted

Dodge-Lynch says she's adjusting more and more each day, but she has to think five steps ahead.

"It has taken quite a long time to do my everyday things in the morning, and then my children are getting ready for school and my husband is there and we're all getting breakfast and doing lunches, and it tires me out," she said.

She says she can stand in the shower now — but there are other issues that presented themselves.

"Opening a shampoo bottle, opening your conditioner — trying to squeeze it out, when you don't have the hand strength," she said.

"I had to learn how to put on a pair of socks, because I can't grab them the way I would love to."

"All the everyday things that you take for granted mentally exhaust me, as well as physically."

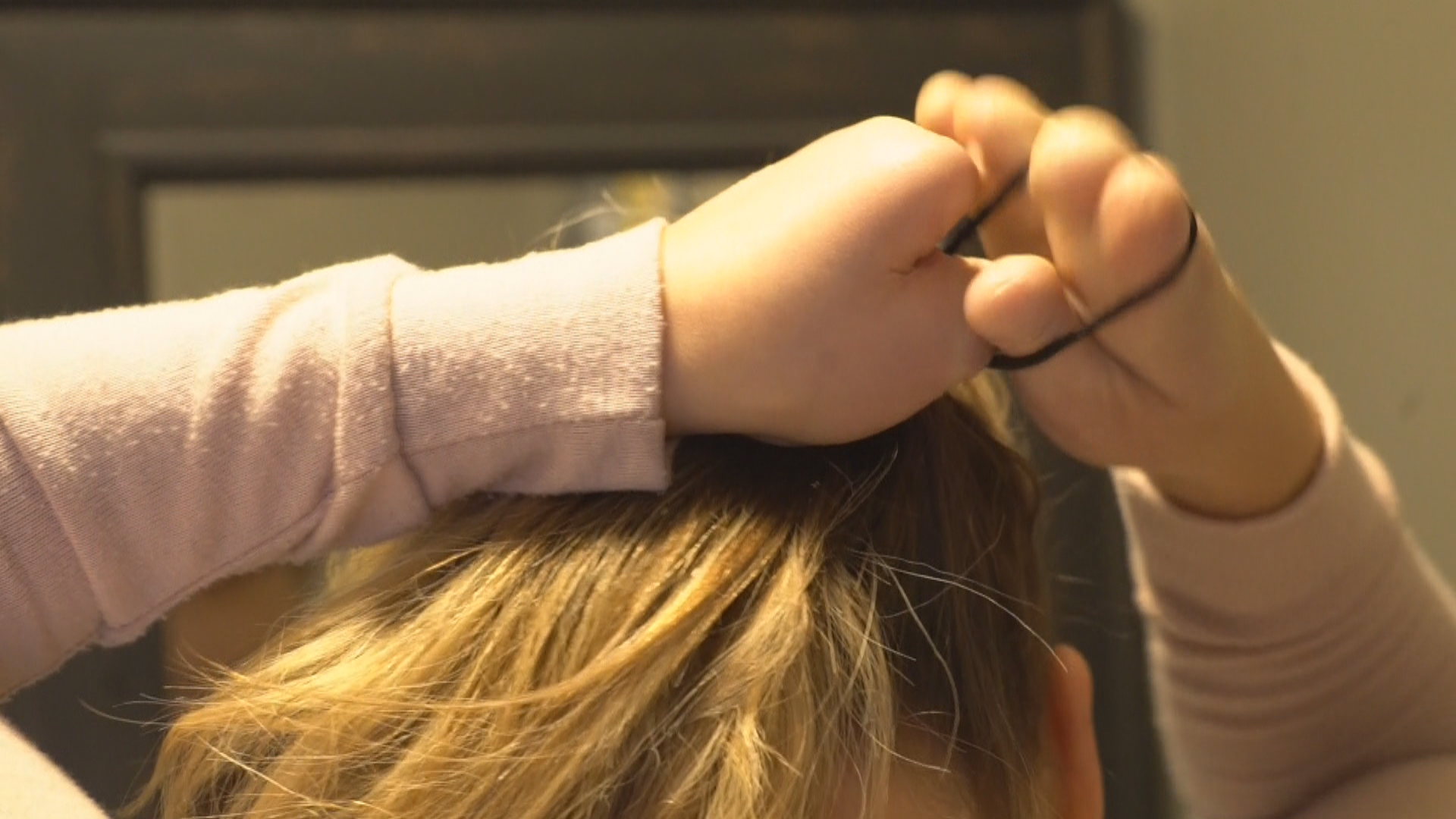

She says learning to do her hair again took a lot of practice, but it was something she was determined to do.

"Initially, when my fingers were so tender and so sore, the occupational therapist was trying to come up with some way for me to just do a ponytail. Because I didn't want to cut my hair off," she said.

But it's when she talks about her daughter that she tears up.

"She has long, beautiful hair and I need to be able to do her hair... I want to make her feel good; that her mom can do things."

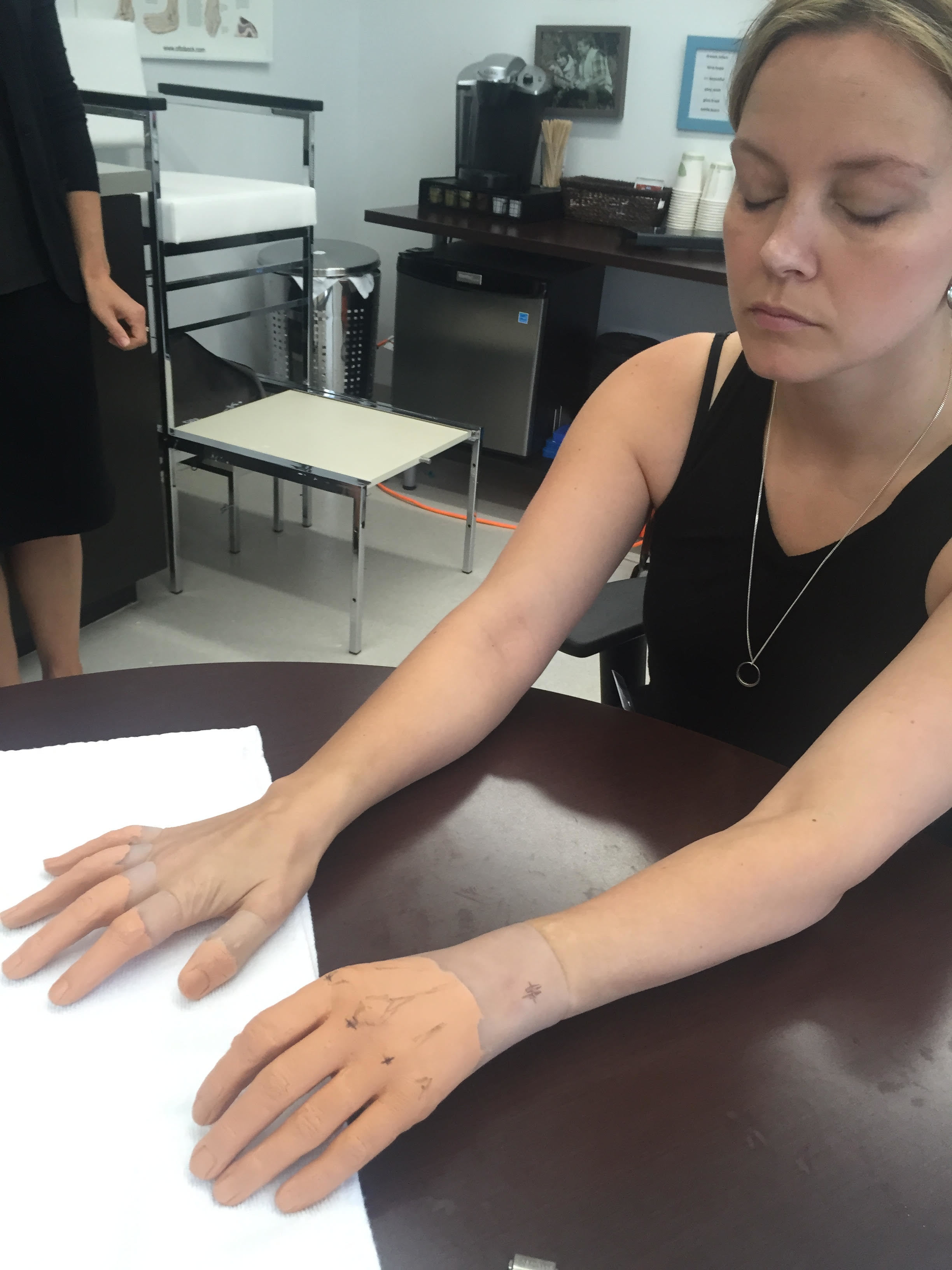

Getting her new hands and feet

Dodge-Lynch says her prosthetics were a long time coming — a full year and a half after her amputations, even though her husband had started investigating options when she was still in a hospital bed.

"We waited that long because your residual limb, it changes shape and all the swelling and all that stuff has to settle down before you can even think about getting prosthetics," she said.

The couple travelled to Ontario, and spent four full days in the silicone lab for Ottobock, the manufacturer, where they took castings of her limbs.

"I had to decide on the shape of my fingers and toes," she said, noting that she got to pick out the details, like nail size, colour, and shape.

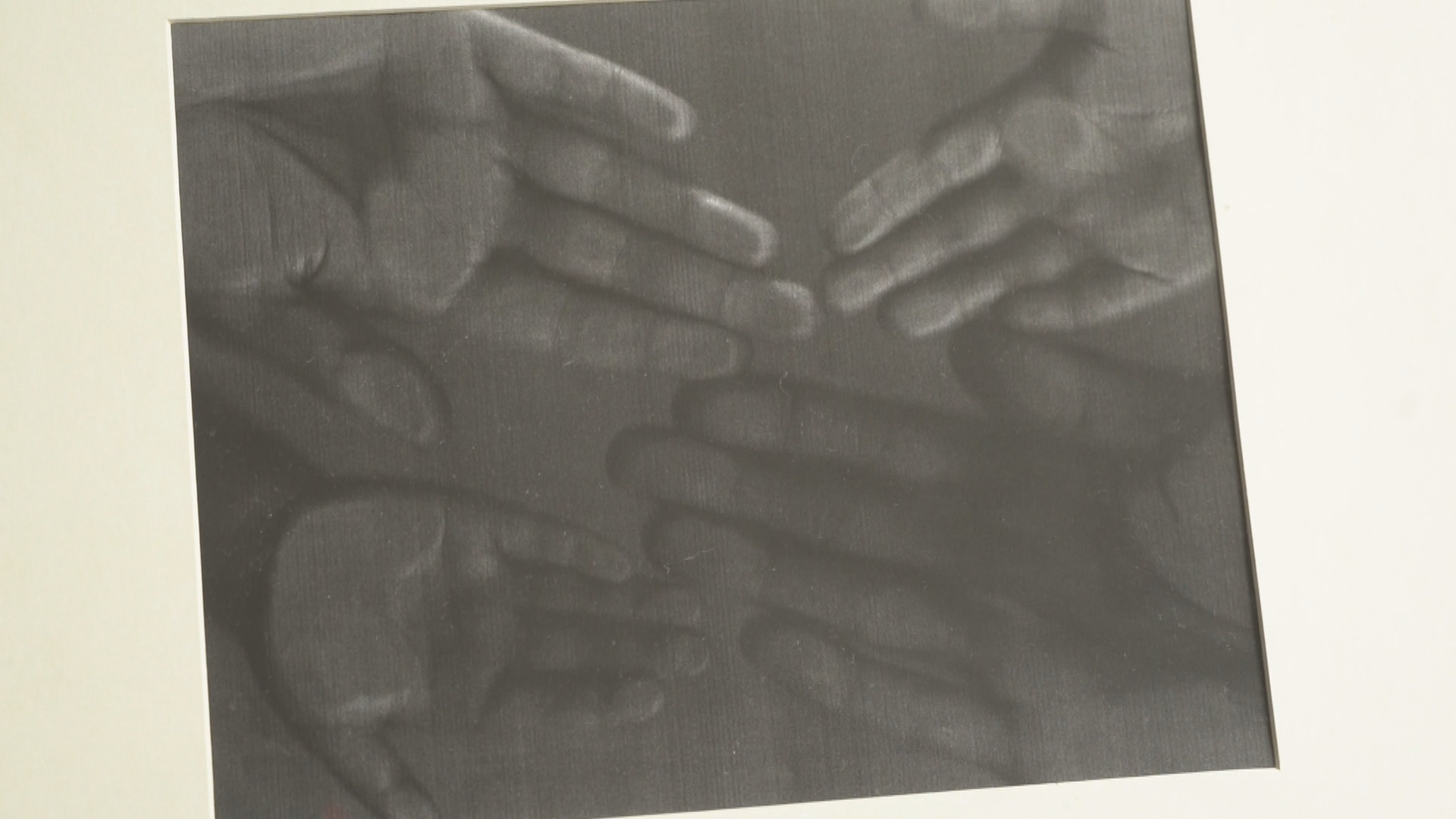

"But this shape for my hand and the length of my hand was done from a photocopy my kids wanted to do," Dodge-Lynch explained.

"Before I got sick — I don't know why; we were just fooling around one day — and we all put our hands on the photocopier and photocopied our hands.

"So I brought the photocopy with me [to Ottobock], and they took those dimensions from my hands. And I'm like, 'Whoever thought I would have needed that?'

"And we have it framed on our wall [now] because it's really important."

There's an equally touching story about her prosthetic feet.

"I just couldn't describe how... I could picture my toes; I just couldn't show them," she said.

"So I got my mom to cast her feet for me — so I have my mom's toes."

Using her prosthetics

Dodge-Lynch puts some specialized gel on the bottom of her legs, and demonstrates how she slips on her prosthetic feet.

"[The gel] helps make a nice vacuum in my prosthetic," she said. "Slips on like a glove."

Dodge-Lynch also uses the gel to help her put on her full left prosthetic hand. She then does up a zipper that's hidden under a flap.

She applies more gel to her forearm, which she uses to put on the prosthetics for her right hand: a set of five separate fingers

"Honestly, I can handle the feet. The hands... I love the look of them. But realistically, they get in the way," she said.

"I tried to drive with them one time, and I looked at the wheel, and one finger was pointing [the opposite way because] they turn."

Dodge-Lynch says it's worthwhile for her to wear them if she's going out somewhere, but for day-to-day life, they don't function very well.

"They are pretty," she said. "But it almost feels like I have a Halloween costume on sometimes, because I have these big extensions on my fingers."

Dealing with chronic pain

Aside from the physical challenges, Dodge-Lynch says she also has to contend with chronic pain.

"There's always some kind of pain, from one day to the next," she said.

"When I get up in the morning, when I put my feet down on the floor, I don't know if they're going to hurt or not... I'm [either] like 'Oh, thank god,' or 'Oh, it's going to be one of those days."

Dodge-Lynch says she also feels pain in her left hand, because the amputation was below the knuckle level.

"I get a lot of phantom pain... so sometimes it feels like my fingers are still there."

"When all this happened, my fingers turned completely black and they were locked in a position — and that's the way it feels; it's like they're locked.

"So even when it feels like I have fingers, I can't move them. It's very frustrating."

The amputations and chronic pain have also meant that, for Dodge-Lynch, work is off the table. She has a PhD, and was working at MUN as a research scientist and a teacher, but her physical state has limited her capabilities.

"My job is a lot of hands-on. I worked in the laboratory. So I can't work with chemicals; I can't do the fine hand manipulation that I used to have to do," she said.

"I can't be on my feet five days a week. I can't type five days a week... Because of the way I walk, my back flares up, [and] I can't sit down at a computer and talk into a computer for five days a week."

'Your new normal'

Dodge-Lynch says she doesn't think about that life-changing moment too often anymore; it's something she tries not to dwell on.

"Sometimes, it seems like yesterday; sometimes, it seems like it was 20 years ago. Because, the sad part is, I can hardly remember what I was like before," she said.

"I had 37 years with fingers and toes, and I can't remember much of it."

"Every now and then, my daughter will ask, 'Mom, do you have any nail polish I could use?' ... Just little things like that kind of hit you hard."

Dodge-Lynch gets emotional when she talks about what pushed her during her rehabilitation.

"My kids, 100 per cent," she said.

"They needed a mom to do what a mom does. And I love them so much, and I can't be the type of person that just says, 'Well, do it yourself, or let someone else do it for you.' It was them."

When asked about what she'd say to someone in a similar situation, Dodge-Lynch stresses it's important to try your hardest, because it's a physical thing — not something more severe, like a chronic illness.

"What you have to focus on is who you're doing it for and not just yourself, because if everyone around you is your support system, then you'll be fine," she said.

"Just be tough and work through [the pain] and it will get better eventually... Things will turn around and your new normal will become normal."

This Is My Story

This Is My Story is a special series from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador, where we check back in with people who have overcome some tremendous struggles in their lives.