Forever chemicals are contaminating the largest surface freshwater system on Earth.

There has been evidence for a few years that levels in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence were higher than the national average, but not high enough to cause immediate alarm.

But what is considered safe is evolving, as research increasingly links forever chemicals to an array of potential health risks, such as cancer and reproductive issues.

Health Canada recently lowered the recommended drinking water limit for forever chemicals to a total sum of 30 nanograms per litre. A nanogram is one billionth of a gram.

The previous limits applied to just two types of the chemicals, allowing up to 600 ng/l of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and up to 200 ng/l of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA).

That change has prompted calls for more oversight of forever chemicals in the Great Lakes, which supply drinking water to one-fifth of the Canadian population.

Forever chemicals, which can last for hundreds or even thousands of years in the environment, are a group of more than 15,000 human-made compounds also known as perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

The water- and grease-resistant chemicals were first used in the late 1940s to make Teflon non-stick cookware. It wasn’t until the late ’90s that concerns over health effects emerged.

Today, a growing body of research has linked some PFAS to a range of potential health risks, including cancer, reduced vaccine response, reproductive issues, delays in child development, hormonal issues and increased cholesterol levels.

The chemicals have leached into the environment over decades of use and they are expected to continue to increase.

Has your water tested positive for PFAS or would you like to report a case of contamination? We’d like to hear from you. Send an email to ask@cbc.ca.

Quebec toxicologist Marc-André Verner said the current thinking is there may be no safe level of exposure.

“The lower the exposure, the lower the risk,” he said.

Université de Montréal environmental chemistry professor Sébastien Sauvé, one of the scientists at the forefront of PFAS research in Canada, has analyzed hundreds of tap water samples for contamination.

Sauvé said his 2018 study found median concentrations of 15 ng/l PFAS in tap water from the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence, compared to a median of four ng/l in tap water from the rest of Canada.

Sauvé said elevated levels in the region could be cause for concern, especially if they increase or if the 30 ng/l objectives are reduced.

“Most of the time, as we accumulate more toxicological information, more epidemiological studies, we end up lowering and lowering the criteria and making them more severe,” he said.

If that happens, Sauvé said, then “all of the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes system is becoming a problem, because they’re at two-thirds of their [current] allowance.”

Around eight million Canadians rely on the system for drinking water, and about 40 million people total if you include people living in the U.S.

Compared to Canada’s broad recommended limit of no more than 30 ng/l total PFAS in drinking water, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency takes a more targeted approach.

For instance, it recommends that PFOS and PFOA, two of the most well-known types, be below zero in drinking water, with an enforced limit of no more than four ng/l each. Since coming into power, Donald Trump’s administration has given utilities more time — until 2031 — to meet those standards.

Verner, who is an associate professor at the school of public health at l’Université de Montréal, pointed out that Health Canada’s guidelines don’t mean that 30 ng/l of PFAS is necessarily safe.

That limit is not solely based on risk, but also takes into account what’s technologically feasible in terms of filtering the chemicals from water.

He said what matters is people’s overall exposure to PFAS — not just through drinking water but also through the food they eat.

“The risk can be different for two people drinking the same water but with different dietary habits,” Verner said.

CBC News reached out to major cities that draw drinking water from Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River to ask them what they’re doing to address PFAS.

Toronto, Montreal and Quebec City said they don’t use treatments specifically designed to remove PFAS, but so far, their levels are within the recommended limits.

The City of Hamilton said forever chemicals in its raw water supply are generally below detection levels, and it also uses granular activated carbon in its water treatment process, which helps to remove PFAS.

Where are the chemicals coming from?

Scientists generally attribute the elevated levels in the Great Lakes to the concentration of industry and people living there.

Master’s student Ignacio Martin Ceballos has been working with Dorner’s lab, the Industrial Chair on Drinking Water at Polytechnique, to compare PFAS in the raw source water to PFAS in treated drinking water in the Greater Montreal area.

The research, which has not yet been peer reviewed, found that the St. Lawrence is contaminated with forever chemicals and that conventional water treatment isn’t removing them.

“What comes in is what comes out,” Dorner said.

That’s in line with a recent federal report that concluded most PFAS is not removed by most conventional water treatment processes and requires advanced technology, such as granular activated carbon.

The good news is that the PFAS levels Dorner’s lab found in the raw water supply all met Health Canada’s objectives.

But as long as the chemicals continue to pollute the environment, there’s a concern they will accumulate.

“These are very persistent compounds,” Dorner said.

“If the focus can be put more on the upstream aspect of it, reduction at source … It’s better for everyone downstream.”

Forever chemicals can spread from sources like landfills, industrial and municipal wastewater, as well as from firefighting training sites.

Cosmetics, waterproof clothing, stain-resistant carpeting and non-stick cookware are just a few examples of the range of products that contain PFAS.

“They still don’t degrade very quickly. So anything that we just release into the St. Lawrence system will stay there and just flow along the river into the ocean, for the most part,” Sauvé said.

A cautionary tale

Other scientists have noticed similar trends in the Great Lakes watershed — and share Sauvé’s concerns about the long-term consequences.

PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyls, were widely used in coolants and lubricants in electrical equipment.

Even though they were banned across North America by the late ’70s due to potential health risks, the chemicals are still found in the environment 40 years later.

McGoldrick, the head of Great Lakes water quality monitoring and surveillance for Environment and Climate Change Canada, said PCBs are still responsible for the majority of fish consumption advisories in the Great Lakes.

Forever chemicals take even longer to break down than PCBs.

“It’s why we’re worried about them. They’re more persistent,” McGoldrick said.

The latest U.S.-Canada binational State of the Great Lakes Report underscores that concern, noting that while PCB contamination in fish has decreased, PFAS contamination is a new concern.

In fact, the Ontario government has issued advisories due to forever chemical contamination in several fish species in Lake Superior, Lake Huron, Lake Erie, Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River.

Like playing a game of whack-a-mole

One hopeful sign: regulations seem to be working.

Sauvé said concentrations of certain types of forever chemicals in the St. Lawrence River seem to be very slowly decreasing or staying stable.

On the other hand, he said, “the types of PFAS are changing and we have not done a proper survey of ultrashort-chain PFAS.”

It’s why scientists have dubbed it the whack-a-mole problem.

When specific forever chemicals have been mostly banned or phased out in North America, namely long-chain PFOA and PFOS, industry has responded by replacing them with new, less studied ones called short-chain.

In other words, while some PFAS are declining in the environment, others are taking their place — and it remains to be seen what that means for ecosystems and human health.

A 2024 peer-reviewed study co-authored by Dove found that PFOS and PFOA appear to be decreasing in the Great Lakes, while newer short-chain forever chemicals are remaining high or increasing.

Dove also pointed out that even the PFAS that appear to be decreasing in the lakes aren’t necessarily disappearing — they could be breaking down into other types of PFAS, or migrating elsewhere.

Dove said it’s critically important to continue monitoring the chemicals in the Great Lakes, and even expand their work to better track specific sources of the pollution.

“We just don’t have a really good handle on what’s coming down in tributaries,” Dove said.

“There’s a lot that we know, but there’s a lot that we don’t know,” she said.

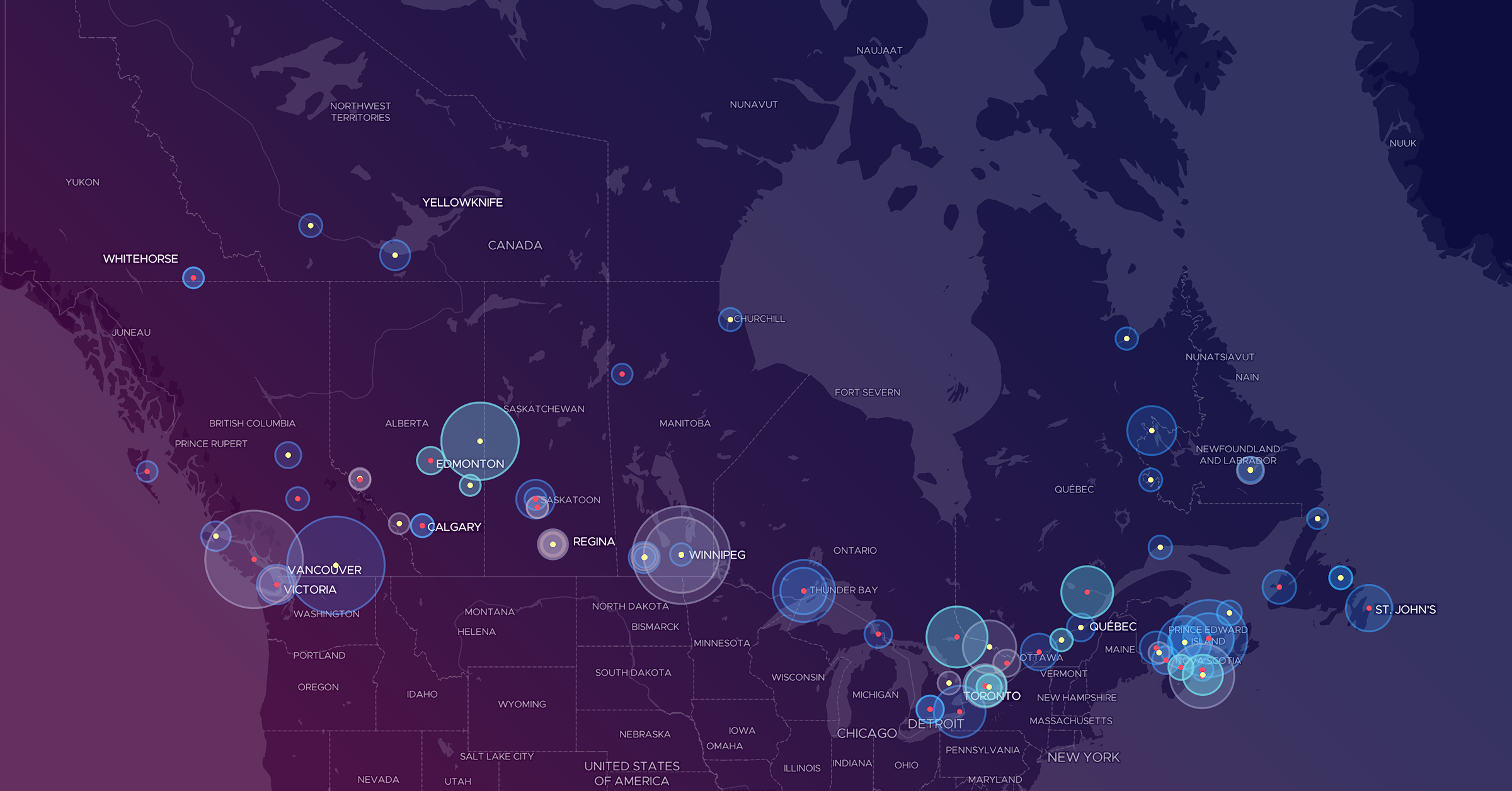

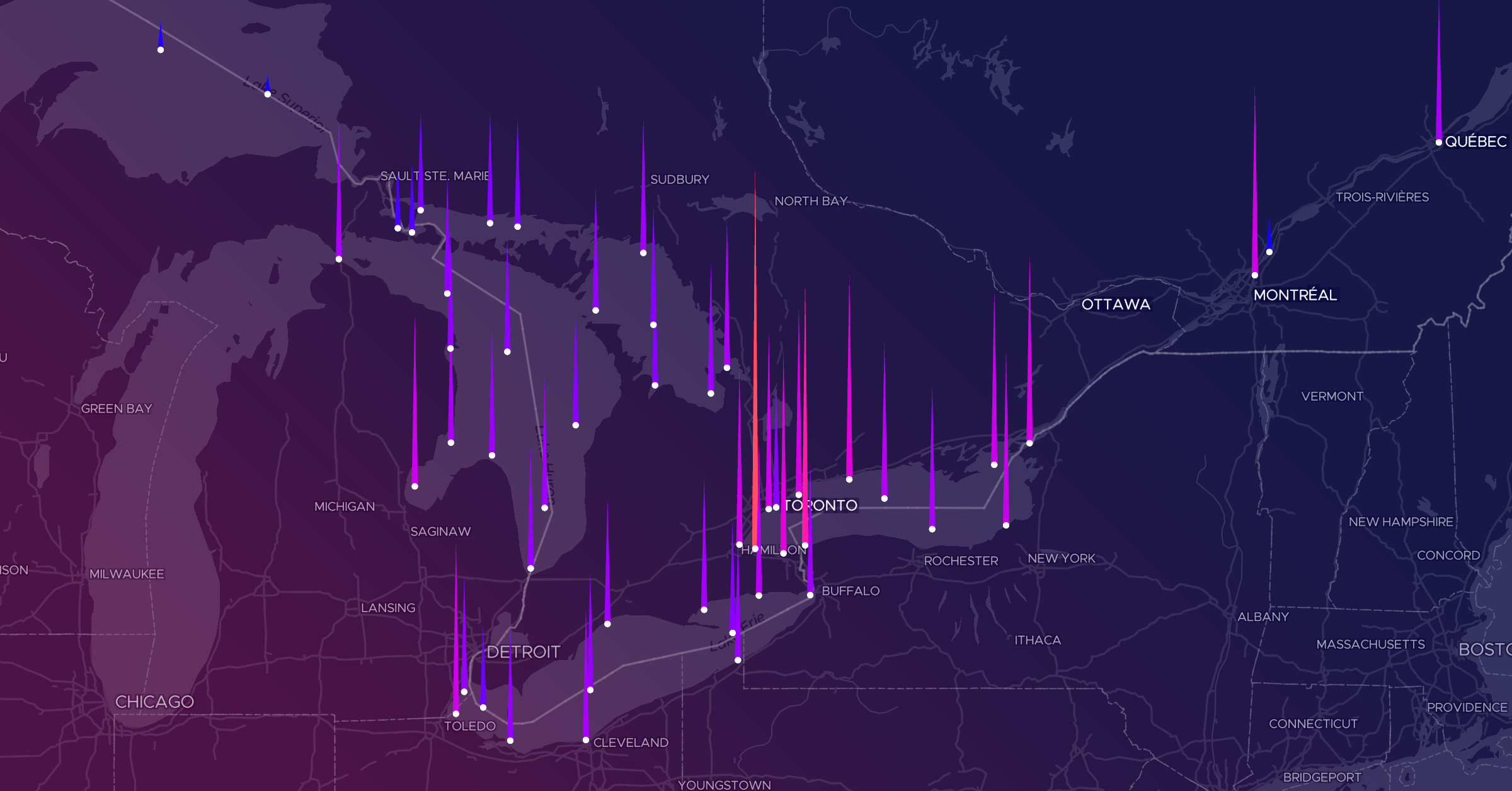

The map in this project shows snapshot-in-time PFAS concentrations from sampling carried out by Environment and Climate Change Canada between 2016 and 2024. The PFAS values are based on an analysis of the sum of the 17 most abundant PFAS detected in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. No data is shown for Lake Michigan because it’s located fully in the United States and not monitored by ECCC. (Source: Water Quality Monitoring and Surveillance Division/ECCC)

Map data from OpenStreetMap and OpenMapTiles.

MORE

Footer Links

My Account

Contact CBC

- Submit Feedback

- Help Centre

- Audience Relations, CBC

P.O. Box 500 Station A

Toronto, ON

Canada, M5W 1E6 - Audience Relations, CBC

Toll-free (Canada only):

1-866-306-4636 - TTY/Teletype writer:

1-866-220-6045

Services

Accessibility

- It is a priority for CBC to create a website that is accessible to all Canadians including people with visual, hearing, motor and cognitive challenges.

- Closed Captioning and Described Video is available for many CBC shows offered on CBC Gem.

- About CBC Accessibility

- Accessibility Feedback