The water plant’s general manager, Rodney Bouchard, is partnering with researchers to analyze concentrations of forever chemicals in the water he supplies to about 70,000 people — and the largest concentration of greenhouses in North America.

Forever chemicals, also called perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), are ingredients in everything from waterproof outdoor gear to makeup and stainproof carpets.

Initially promoted as stable and safe, the class of more than 15,000 synthetic compounds have been largely unmonitored and unregulated for decades, spreading into the environment through municipal and industrial wastewater, landfills and from contaminated sites.

That’s all changing as evidence of serious health risks mounts.

Regulators are pivoting, including the Canadian government, which dramatically reduced the recommended limits for PFAS levels in drinking water and is planning to add PFAS to the official list of toxic substances.

Now municipal water providers are on the hook to figure out how to treat and remove the chemicals. Operators across the country are investigating whether they have the contaminants in their water, at what concentrations, and if so, what sort of upgrades will be required to get rid of them.

“We need to know what we’re dealing with before we can adapt,” Bouchard said.

The human-made compounds are used in a variety of products, ranging from waterproof clothing to fast food containers, and studies have linked some of them with cancer, reduced vaccine response, reproductive issues, delays in child development, hormonal issues and increased cholesterol levels.

More than 98 per cent of Canadians have forever chemicals in their blood, according to Statistics Canada.

Previous federal limits for safe concentrations of PFAS in drinking water only applied to PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonate) and PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid), allowing for up to 600 nanograms per litre and 200 nanograms per litre, respectively.

One nanogram is about the weight of a single human cell.

The new recommendations, which are not enforced, drastically reduce those limits to 30 ng/l total, a sum of 25 types of PFAS.

The good news for Rodney Bouchard’s utility is that sampling last fall at Union Water Supply found levels that are well within the new standards — a total sum of 13 ng/l.

That testing was done by University of Waterloo chemistry professor Scott Hopkins, who is screening for PFAS at water utilities across southern Ontario.

He said average results across all the water utilities he’s tested have ranged from five to 15 ng/l, which he compares to a Coca-Cola bottle’s worth of water in Lake Erie.

“No alarm bells, but definitely worth monitoring and trying to come up with some sort of strategy for how we would handle this in the future,” Hopkins said.

Since forever chemicals can take hundreds of years to break down, scientists aren’t just concerned about what’s in the water today — but also in the future as forever chemicals continue to build up.

“Those concentrations that we have in the environment I don’t think are going to drop unless we force them down. We put the molecules there. The environment is not able to handle it. It’s up to us to take them out.”

Other places in Canada are already facing obstacles in removing PFAS from drinking water. Towns such as Bagotville, Que., North Bay, Ont., and Torbay, N.L., are among those with PFAS contamination in their drinking water, which can cost millions of dollars to address.

That’s because when water utilities do find themselves with levels above 30 ng/l, the task of cleanup is expensive — and extremely difficult.

The fact is, if a water treatment plant or a private well owner isn’t already using specialized technologies, any forever chemicals in the source water are likely passing through.

“It’s going to be challenging for some municipalities out there, because they just don’t have the resources,” Bouchard said.

Health concerns spark global crackdown

“Conventional drinking water treatment is not effective for removing PFAS compounds,” said Polytechnique Montréal professor and environmental engineer Sarah Dorner.

Dorner, an expert in water quality, has been supervising research into PFAS in water in the Montreal area.

While treatment is possible with the right technology, she said the best approach is preventing pollution in the first place.

“Control at the source is really important,” she said.

Many countries are trying to tackle the issue from both sides, by cracking down on the use of forever chemicals while also setting limits for drinking water.

France recently voted to limit the use of PFAS, and the European Union has an overall limit of 100 ng/l for the sum of 20 types of PFAS in drinking water.

In Denmark, the limit for four types of PFAS in drinking water is two ng/l and in Sweden the maximum is four ng/l.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency introduced new rules in 2024 under president Joe Biden, including a legally enforceable limit of four ng/l for PFOA and PFOS individually.

At the time those rules were announced, the EPA also recommended a goal of zero for both PFOA and PFOS, because “there is no level of exposure to these contaminants without risk.”

President Donald Trump’s government announced plans to roll back some of those rules, though it’s keeping the limits on PFOA and PFOS while giving utilities more time to meet them (they now have until 2031).

In Canada, the federal government has announced plans to expand its restrictions on the manufacture, use, sale and import of PFAS, which currently only apply to three types: PFOS, PFOA and long-chain perfluorocarboxylic acids (LC-PFCAs). Though that process is expected to take years.

Hopkins said he’d like to see that process move along more quickly.

“Chemicals don’t care about borders,” he said.

“It’s starting to be phased out, but all of those products that we’ve brought in for the last 30, 40 years — if they’re not in your closet, they’re in the landfill and those molecules aren’t going away. They’re going to get out into the environment somehow.”

A group of 13 Canadian scientists have signed a letter calling on the federal government to take more concrete action on PFAS — and faster. Their recommendations include making the 30 ng/l limit a legally enforceable standard, and instituting a more systematic approach to testing drinking water near known PFAS-contaminated sites.

University of Toronto environmental chemist Miriam Diamond, who wrote the letter, said she’s worried about future generations.

“While we’re taking time to respond, PFAS is being produced, developed, used and released — increasing the environmental burden,” Diamond said.

While calls mount for urgent action, others have voiced doubts that the new drinking water recommendations aren’t realistic.

“I’m not sure this is feasible at all,” said Grant Carey, who is an adjunct professor at both Carleton University in Ottawa and the University of Toronto.

Carey, who runs an Ottawa-based PFAS remediation consulting company called Porewater Solutions, said some water utilities might not be able to meet the 30 ng/l threshold.

“I think the regulations in Canada are far more strict [than U.S. regulations],” said Carey, who works mainly on U.S.-based contaminated sites.

He said the issue with the Canadian approach is that it applies to both long- and short-chain forever chemicals. The “chains” in the name refers to the length of the carbon chain in the compounds.

Has your water tested positive for PFAS or would you like to report a case of contamination? We’d like to hear from you. Send an email to ask@cbc.ca.

The issue, Carey said, is that the most common approaches for treating PFAS aren’t as effective with the short-chain varieties.

Short-chain PFAS, such as PFBA, became more common as industry started to use them as substitutes when long-chain forever chemicals, such as PFOA and PFOS, were regulated or banned.

Short-chain forever chemicals have been less studied and were initially thought to be safer. But recent research has suggested they could have toxicological potential in mice and may disrupt immune function in alligators.

Who will pay?

Robert Haller, executive director of the Canadian Water and Wastewater Association, said it’s too early to say whether the 30 ng/l objective will be feasible.

Many utilities don’t even know what level of forever chemicals they have in their water, let alone how much of that, if anything, is removed through their current treatment process.

He said it’s not like utilities can just “throw another filter on” to solve the problem.

The technology required to treat forever chemicals for public water supplies can cost millions of dollars in upgrades.

That’s why whatever standard governments decide to enforce, Haller said it must come with funding.

“It’s one thing to make a regulation at a desk, it’s quite another thing to implement it and fund the upgrades,” Haller said.

So far, most methods for dealing with PFAS in water remove it rather than eliminating it, which leaves the problem of where and how to store the toxins once they’re filtered out.

Kela Weber, professor and director of the Environmental Sciences Group at the Royal Military College of Canada, said the fact there is no proven, commercially available, economically viable solution to destroying PFAS is limiting action.

“Everyone’s in this risk mitigation mode. And, perhaps, I-don’t-want-to-know mode, in some cases,” Weber said.

“As soon as solutions get out there, things will move.”

The good news is there has been progress around developing new approaches, including the use of burnt wood chips by researchers at the University of British Columbia.

Weber is developing a solution as well, one that’s successfully destroyed not only long-chain but also short-chain PFAS in the lab.

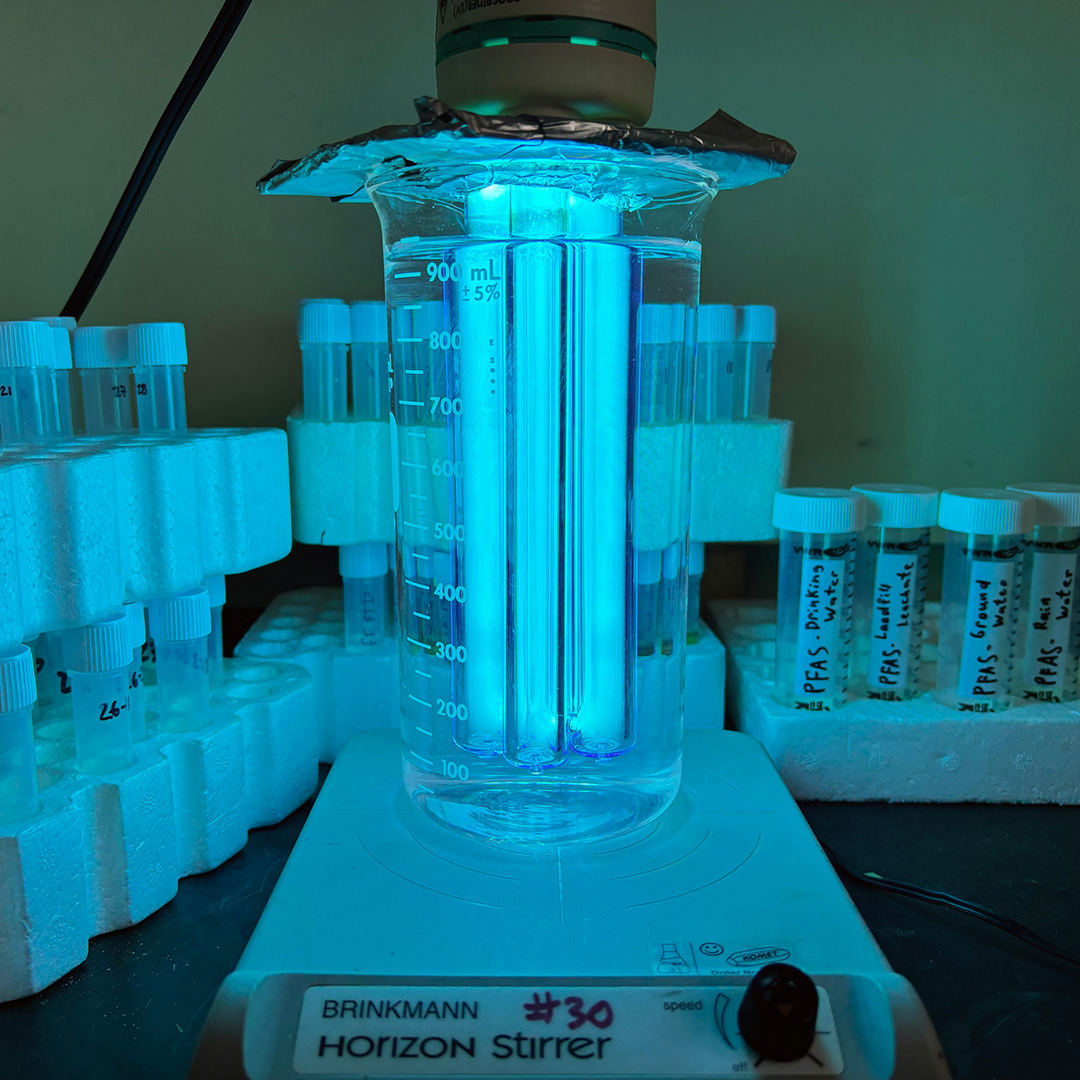

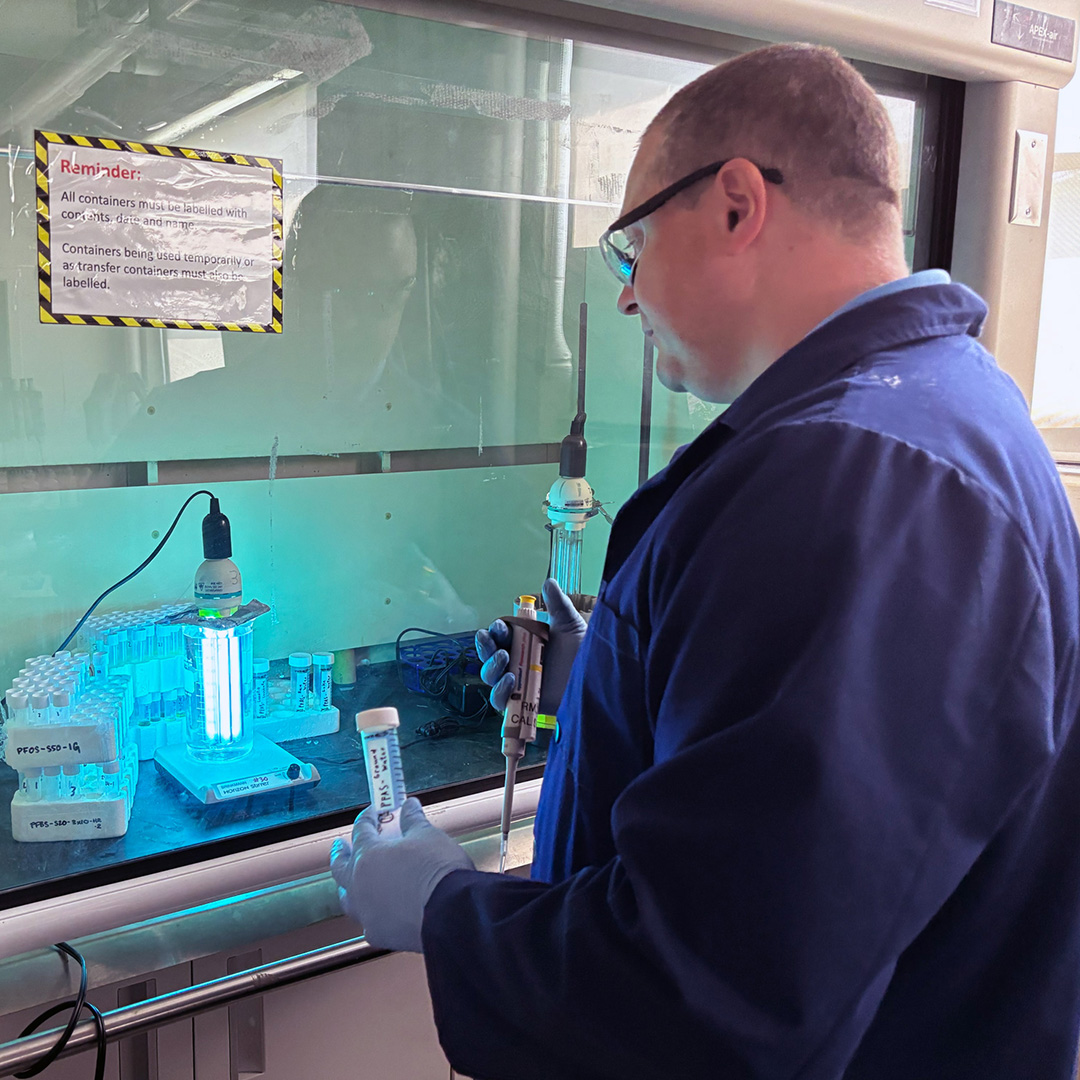

It’s called RADIANT, which stands for Reactive Activation of Iodide and Sulphite through UV-Natured Treatment. It does exactly what its name suggests, combining sulphite and iodide with ultraviolet light to eliminate PFAS in water.

Now Weber’s team is testing the technology in the real world, partnering with the Ontario Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks to see if RADIANT works on groundwater samples.

The federal recommendations are, for now, interim goals and non-binding. It will be up to the provinces and territories to decide what to enforce.

Some regions have previously established standards for PFAS that might need to be revised; Ontario, for example, limits concentrations to a total of 70 ng/l.

As for people who rely on private wells — Health Canada has guidance on at-home solutions, including tap-mounted activated carbon filters, reverse osmosis systems and ion exchange systems.

Costs range from $50 to hundreds of dollars, depending on the level of filtration needed.

Forever chemicals have no scent or taste, so homeowners wouldn’t likely know their well water is contaminated unless they’ve had it tested.

Quebec toxicologist Mark-André Verner, an associate professor with l’Université de Montréal’s school of public health, said most Canadian communities actually have relatively low levels in their water.

Though there are cases of drinking water contamination in the country, research so far suggests that on average, PFAS levels in drinking water are secondary to concentrations in certain foods like fish, seafood and other types of meat.

People can also be exposed through dust and contact with products like stain-resistant carpets, waterproof makeup, nonstick cookware and microwave popcorn bags.

“They’re just everywhere now. So we’re being exposed every single day,” Verner said.

So why limit PFAS in drinking water? The thinking, according to Verner, is that contamination in water can be controlled with some success.

“Drinking water is something we can act on,” he said.

“The lower the exposure, the lower the risk.”

MORE

Footer Links

My Account

Contact CBC

- Submit Feedback

- Help Centre

- Audience Relations, CBC

P.O. Box 500 Station A

Toronto, ON

Canada, M5W 1E6 - Audience Relations, CBC

Toll-free (Canada only):

1-866-306-4636 - TTY/Teletype writer:

1-866-220-6045

Services

Accessibility

- It is a priority for CBC to create a website that is accessible to all Canadians including people with visual, hearing, motor and cognitive challenges.

- Closed Captioning and Described Video is available for many CBC shows offered on CBC Gem.

- About CBC Accessibility

- Accessibility Feedback