Airports, military bases, former landfills and firefighting training sites across Canada are polluted with forever chemicals — and a CBC News analysis has revealed some of those sites could pose a threat to drinking water.

Forever chemicals, also called perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), have been used for decades in a variety of products.

In 2024, Health Canada updated its guidance to recommend limiting levels in drinking water to 30 nanograms per litre. A nanogram is a billionth of a gram, or about the weight of a single human cell.

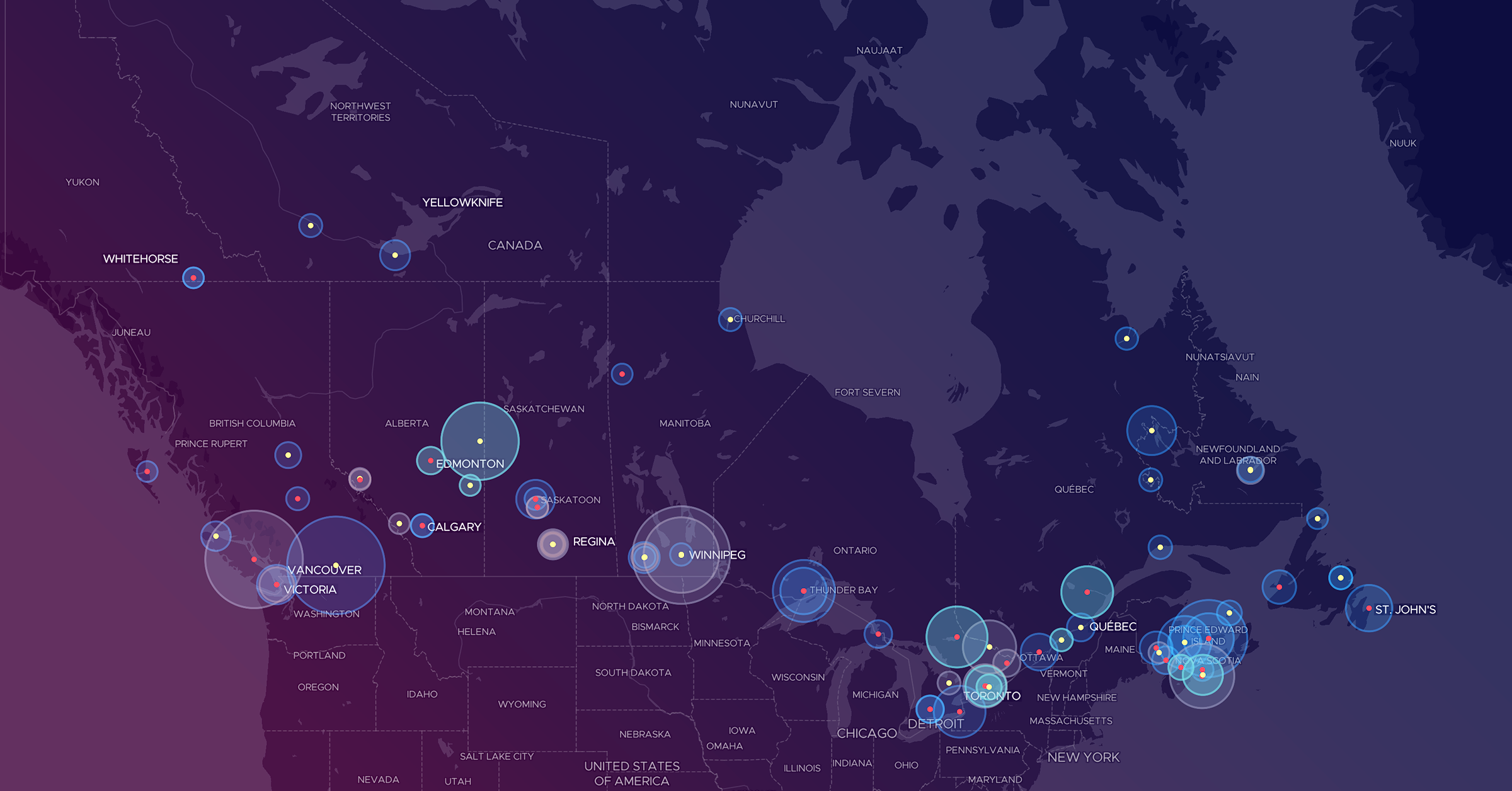

As federal and provincial authorities adapt to the new recommendations, which are not yet enforced, CBC News has put together an interactive map showing PFAS hotspots in Canada.

Every province and territory has sites contaminated with forever chemicals. These are all the locations listed where PFAS have been identified or are suspected, according to Canada’s Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory.

Some hotspots are well-known, others less so.

In locations where PFAS have seeped into the groundwater, the chemicals could spread to nearby wells in certain circumstances, depending on the direction of groundwater flow and other factors. CBC News cross-referenced PFAS-contaminated sites with provincial and federal well records to identify locations where drinking water wells are within a one-kilometre radius.

Wells within 1 km

No known wells within 1 km

At many of these sites, PFAS have spread to more than just water.

For the purposes of this project, “groundwater” is water found underground. “Surface water” refers to above-ground waterbodies such as rivers and lakes. “Soil” includes soil and earth down to a depth of 1.5 metres, as well as sediment settled at the bottom of water bodies.

Groundwater

Soil

Surface water

Forever chemicals are notoriously difficult to clean up once they spread beyond a contaminated site. Some hotspots are in cities, with more than 1,000 people living within one kilometre, while others are in far-flung locations with few — or no — neighbours.

250

500

750

1,000+

Let’s take a look at some examples.

PHASE

Suspected

Assessment

Remediation/risk management

Long-term monitoring

CONTAMINATED AREAS

Groundwater

Soil

Surface water

WELLS

Wells within 1 km

POPULATION

404 within 1 km

NOTES

- National Defence detected PFAS levels above 30 ng/l in four of 24 neighbouring wells sampled in 2023.

- City of Saguenay reported in 2024 that measures are working; PFAS no longer detected in water.

- National Defence contracted the removal of about 80,000 tonnes of PFAS-affected soil in 2025.

In 2022, Université de Montréal environmental chemistry professor Sébastien Sauvé was sampling tap water when he made a shocking discovery: forever chemicals had spread from the Bagotville military base to wells up to 10 km away.

The contamination resulted in PFAS levels up to six times the recommended limit in the public drinking water of La Baie, a borough of Saguenay, Que.

Since then, federal and municipal authorities have closed a contaminated municipal well and invested $11 million in temporary filters. According to the City of Saguenay, those measures are working; the latest round of testing found no traces of PFAS in treated drinking water.

The city is now searching for a new water source.

PHASE

Suspected

Assessment

Remediation/risk management

Long-term monitoring

CONTAMINATED AREAS

Groundwater

Soil

Surface water

WELLS

Wells within 1 km

POPULATION

524 within 1 km

NOTES

- National Defence has tested wells at 162 properties since 2023; 66 of those had levels above 30 ng/l.

- Alternate water supply provided to homes with levels above 70 ng/l, based on provincial limits.

- Fish consumption advisory in effect.

- City of North Bay began remediation of adjacent airport lands in Fall 2024 with federal financial support.

- Monitoring ongoing and work underway to determine potential remedial options.

In North Bay, Ont, forever chemicals from firefighting training exercises at the airport decades ago have seeped into Trout Lake, the source of the city’s drinking water.

The Department of National Defence told CBC News it found concentrations of PFAS above 30 ng/l in the wells of 66 out of the 162 homes it tested in the area.

The federal department said it is providing an alternate water supply, but only to homes that exceed Ontario’s provincial PFAS limits of 70 ng/l, more than double the latest federal guidelines.

As previously reported by CBC, the Department of National Defence covered most of the $20-million bill to remove and treat contaminated soil from the airport and the city is now exploring options to upgrade its water treatment plant to treat the PFAS that remains.

Some sites are quite remote — found as far north as the Arctic Circle.

PHASE

Suspected

Assessment

Remediation/risk management

Long-term monitoring

CONTAMINATED AREAS

Groundwater

WELLS

No known wells within 1 km

POPULATION

5 within 1 km

NOTES

- Independent research has found PFAS contamination in Resolute and Meretta lakes and local Arctic char population.

- Remediation and/or risk management completed.

- Sampling underway.

Even in Resolute, Nunavut, one of Canada’s northernmost communities, PFAS has leached into the environment.

A 2015 study found forever chemicals from firefighting training at the local airport had spread to both Resolute and Meretta lakes, contaminating Arctic char with PFAS levels more than 100 times higher than fish in neighbouring lakes.

Many sites with PFAS contamination are not well-known.

PHASE

Suspected

Assessment

Remediation/risk management

Long-term monitoring

CONTAMINATED AREAS

Groundwater

WELLS

Wells within 1 km

POPULATION

537 within 1 km

NOTES

- Fish consumption advisories issued for the Neebing River due to Thunder Bay Airport contamination.

There are actually two hotspots at the Thunder Bay airport: one at a former landfill site and one at a former firefighting training area. In both cases, forever chemicals have leached into the groundwater.

The Thunder Bay airport authority reported in 2012 that PFAS contamination had been contained. But according to the Lakehead Region Conservation Authority, the chemicals have spread off-site.

Contamination in nearby fish prompted the province of Ontario to issue a consumption advisory warning against eating any creek chub, rock bass and white sucker from the Neebing River.

Michelle Willows, an environmental planner with the conservation authority, connected the advisories to the airport’s former firefighting training facility.

A spokesperson for Transport Canada did not comment on whether nearby wells had been tested for contamination, but did say in an email that the government was evaluating the site on an ongoing basis and “has completed environmental studies and has implemented measures including remediation of the former firefighting training area containment basin.”

Some cases of contamination have sparked lawsuits.

PHASE

Suspected

Assessment

Remediation/risk management

Long-term monitoring

CONTAMINATED AREAS

Groundwater

WELLS

Wells within 1 km

POPULATION

334 within 1 km

NOTES

- Approximately 200 nearby homes potentially affected by PFAS-contaminated water.

- Transport Canada supplied bottled water to some nearby residents as of May 2024.

- Residents filed a lawsuit against federal government.

In Torbay, N.L. residents launched a class-action lawsuit against the federal government in 2024 for failing to warn residents of contaminated water.

As many as 200 homes could be affected by PFAS contamination from a firefighting training site at St. John’s International Airport.

Locals said they only learned there was PFAS in their water in 2024, after Health Canada officially lowered its drinking water guidelines for PFAS from between 200 and 600 ng/l to 30 ng/l.

Transport Canada would not comment on the specifics of the case, but a spokesperson said the department takes its responsibilities related to human health and the environment seriously and that it has arranged for bottled water delivery in cases where well water levels exceed guidelines.

Predicting if and how PFAS will spread from a contaminated site to nearby wells is tricky and depends on a number of factors.

PHASE

Suspected

Assessment

Remediation/risk management

Long-term monitoring

CONTAMINATED AREAS

Groundwater

Soil

Surface water

WELLS

Wells within 1 km

POPULATION

87 within 1 km

NOTES

- National Defence has sampled 15 wells and none exceeded 30 ng/l.

- Analysis of remedial options underway.

- Monitoring of groundwater and surface water ongoing as remediation options analysis is updated.

Even though there are wells within one kilometre of a contaminated site at Canadian Forces Base Edmonton, the National Defence Department said no wells tested nearby had levels above 30 ng/l.

Environmental factors, like the makeup of the soil and the direction of groundwater flow, can affect how far forever chemicals spread.

Federal agencies monitoring contaminated sites in Canada told CBC News they evaluate which wells to test around a contaminated site on a case-by-case basis.

This project is based on the best available national dataset for PFAS-contaminated sites, and does not currently include contaminated sites under private, provincial or municipal authority.

The 80 sites on this map are likely a vast undercount, because the chemicals have not been monitored and reported in a standardized way across Canada, though new requirements will strengthen tracking in the coming years.

As of June 1, 2026, facilities will be required to report quantities of PFAS that are released, disposed of or recycled.

In the meantime, this project offers a glimpse of known federal contaminated sites, most of them linked to the use or storage of a fire suppressant called aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF).

A 2018 research paper by Royal Military College chemical engineering professor Kela Weber estimated there could be as many as 152 airport and heliport sites in Canada contaminated with PFAS, possibly hundreds more, linked to fire suppressant.

That estimate doesn’t include other ways that PFAS can spread to the environment, through municipal wastewater; sewage sludge used as fertilizer; and discharge released by industries like petroleum refineries, paper mills, textile mills and plastics manufacturing.

CBC News reached out to every province and territory to ask for data on PFAS-contaminated sites. In most cases, governments had not been systematically monitoring PFAS contamination, or were unwilling to share that information without an access to information request.

This map will be updated as more information comes to light.

What should you do if you live near a contaminated site?

Research has linked certain PFAS with a variety of potential health effects, including cancer, reduced vaccine response, reproductive issues, delays in child development, hormonal issues and increased cholesterol levels.

Quebec toxicologist Marc-André Verner said the latest science suggests there may be no safe level of exposure to PFAS.

At the same time, the chemicals are so pervasive that it doesn’t take living near a hotspot to be exposed. In fact, the vast majority of Canadians have forever chemicals in their blood. The main way many people are exposed to them is through food, especially fish, seafood and meat.

But if you live near a contaminated site, your drinking water could also be a significant source of exposure.

“If it’s in the underground water and you’re on a private well with the same underground water, then it becomes a concern for you, that’s for sure,” Verner said.

His advice is to find out what levels are in your drinking water, and to find out what local officials are doing to address the issue.

Health Canada advises anyone concerned to reach out to local authorities for advice.

To remove PFAS from drinking water, the federal authority recommends installing an activated carbon filter, a reverse osmosis system or an ion exchange system designed specifically for PFAS removal.

Verner, who is an associate professor at the school of public health at l’Université de Montréal, said people shouldn’t have to pay for at-home filtration systems, which can cost hundreds of dollars.

“We shouldn’t have that burden on people,” he said.

Instead, he said, forever chemicals should be stopped at the source.

The toxic legacy behind forever chemical contamination

Seventy years ago, when forever chemicals first hit the commercial market, they were promoted as safe, stable ingredients used to make innovative Teflon skillets.

When concerns related to PFAS started to emerge in the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was a global push to strengthen control of the chemicals, and momentum has grown in recent years in response to public pressure.

Since 2012, Canada has banned three types of PFAS, with some exceptions, out of the more than 15,000 that exist.

In 2025, the federal government signalled a move toward tighter restrictions, starting with the elimination of PFAS in firefighting foams in the coming years. Health Canada has advised “the lower the levels of exposure to PFAS, the lower the risk.”

There are also plans to label all forever chemicals as toxic, except for one group called fluoropolymers.

On the industry side, U.S.-based manufacturer 3M has announced that it will stop producing PFAS by the end of 2025, in the wake of a multi-billion-dollar settlement with U.S. public drinking water providers.

Chemical giant DuPont told CBC News the company is “currently pursuing alternatives to PFAS where possible.”

Given that PFAS can take hundreds or even thousands of years to degrade, there are concerns they will leave behind a toxic legacy as long as they are in circulation.

Senior Canadian government officials have stated as much, warning that forever chemicals are expected to increase in the broader environment and cannot reasonably be removed once they’ve spread.

Has your water tested positive for PFAS or would you like to report a case of contamination? We’d like to hear from you. Send an email to ask@cbc.ca.

Industries and policy-makers now face a fork in the road: will they choose a future where chemicals continue to contaminate the food we eat and water we drink, or will they curb the toxic legacy of PFAS before it gets any worse?

- A text-based spreadsheet of the information available in this map can be downloaded here.

- This project draws data from the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory, which identifies sites under federal custodianship or that the Government of Canada has accepted some financial responsibility for, that are known or suspected to be contaminated with PFAS.

- For the purposes of this project, we only included groundwater wells that have been explicitly designated for drinking water use or otherwise labelled for public, municipal or domestic use. In Alberta and Newfoundland, only domestic wells are counted, because those provinces do not identify municipal wells in their databases. Well locations are based on the best available data from federal, provincial or territorial well registries, which may not be exhaustive.

- Wells counted were limited to a one-kilometre radius from a contaminated site, based on consultation with multiple experts and standard approaches to PFAS testing. The risk of well contamination is not solely based on proximity, and also depends on hydrogeological conditions, groundwater flow direction and rock and soil types.

- Contaminated sites deemed closed have been removed from the map as of the last update.

MORE

Footer Links

My Account

Contact CBC

- Submit Feedback

- Help Centre

- Audience Relations, CBC

P.O. Box 500 Station A

Toronto, ON

Canada, M5W 1E6 - Audience Relations, CBC

Toll-free (Canada only):

1-866-306-4636 - TTY/Teletype writer:

1-866-220-6045

Services

Accessibility

- It is a priority for CBC to create a website that is accessible to all Canadians including people with visual, hearing, motor and cognitive challenges.

- Closed Captioning and Described Video is available for many CBC shows offered on CBC Gem.

- About CBC Accessibility

- Accessibility Feedback