From a boat on Lake Erie, scientists have launched what they hope will soon be an early warning system to protect locals from a threat lurking in the water.

Dangerous, slimy mats of blue-green algae are plaguing Lake Erie and other lakes across North America, not only interfering with ecosystems and recreational activities, but also complicating municipal water treatment processes.

Blue-green algae are microscopic bacteria found in freshwater, also called cyanobacteria. When certain types of cyanobacteria multiply under the right conditions, they can form thick toxin-producing scum.

Toronto

Leamington

Cyanotoxins can be deadly if they’re consumed by dogs and other animals. In humans, exposure can lead to symptoms ranging from mild to life-threatening: rashes, eye irritation, headaches, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, and liver or kidney damage.

There’s mounting pressure to tackle the threat, as blooms encroach on lakes across the country including in British Columbia, the Prairies, the Great Lakes, Quebec and Nova Scotia, where cyanobacteria blooms likely killed two dogs. Blue-green algae blooms have also popped up in unusual spots like Lake Superior and beaches in Hamilton, where local authorities say blooms used to be rare — if not unheard of.

The problem is well-known in waterfront communities in Southwestern Ontario. The amount of cyanobacteria in Lake Erie has been getting worse since the 2000s, according to the U.S National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

In Lake Erie, the main culprit of the blooms is phosphorus-rich runoff from agriculture and urban pollution — the bulk of it coming from the United States. That, combined with the lake’s shallow, warm waters creates the perfect habitat for the dangerous scum to thrive.

Canada and the U.S. have strived to improve Lake Erie’s water quality since the 1970s, and most recently committed to reducing phosphorus loads by 40 per cent from 2008 levels.

Yet the pollution persists, and the recurring blooms threaten a lake relied on by about 12 million people for drinking water.

Do you have issues with water quality or water shortages? Are you working on an innovative solution around drinking water? We’d like to hear from you. Send an email to ask@cbc.ca.

In 2014, a severe bloom turned into an emergency when toxins infiltrated the water supply in Toledo, Ohio. Half a million people couldn’t use their tap water for two days.

Rather than wait on authorities to fix the root of the problem, one water utility in Kingsville, Ont., is taking matters into its own hands to make sure the tap water won’t be compromised.

Yellow smart buoys bobbing on the surface of Lake Erie are at the heart of a mission to protect the drinking water.

The goal is to create an early warning system for algae blooms, through a collaboration between water operators and scientists.

Scientist Aaron Fisk is overseeing the project.

“We take it for granted that we have all of this water,” he said, gesturing to the lake around him.

“We need to be more serious about it. It is not an inexhaustible thing.”

Fisk is the science director of the Real-Time Aquatic Ecosystem Observation Network (RAEON) and the Canada Research Chair in Changing Great Lakes Ecosystems at the University of Windsor.

In the worst case scenario, a severe toxic bloom could force a shutdown of water utilities. Even if it didn’t come to that, the blooms could disrupt the water treatment process, making it more costly and complex.

That’s where the buoys come in.

Each one is essentially a self-contained weather station, equipped with sensors that monitor everything from water temperature and oxygen levels to currents, chlorophyll and wind speeds.

On a hot day in August, scientists from RAEON and Environment and Climate Change Canada deployed from a marina in Leamington, Ont., to check on the water quality.

Lake Erie is the most densely populated of the Great Lakes, making it vulnerable to pollution.

From the boat, scientists hoisted one of the buoys on board, hosing it off and removing invasive mussels that were blocking its sensors.

By the end of this year, the early warning system is expected to transmit live water quality data directly to the Union Water Supply in Kingsville.

The water utility provides drinking water to 70,000 people in the municipalities of Leamington, Lakeshore, Kingsville and Essex.

About half the water it produces between the spring and fall feeds Leamington’s multibillion dollar agribusiness sector: the largest concentration of greenhouses in North America.

There’s hope that the innovative project could inspire other regions to follow suit, as climate change is expected to increase the likelihood of blue-green algae blooms.

Fisk said it’s satisfying for him as a scientist to have such a direct impact on people’s lives.

“We’re making sure that the greenhouses can grow their food to feed people. We’re making sure that people don’t get sick from water. We’re making sure that people have access to water,” he said.

A critical window to protect the water

Union Water Supply’s general manager Rodney Bouchard is well-acquainted with the threat of blue-green algae blooms.

In 2011, his first year on the job, the bloom was so thick he said Lake Erie looked like a golf course.

“It’s a concern,” he said. “I think they’re going to get worse and worse.”

Not every algal bloom is toxic, but Bouchard said they have to treat every bloom as if it could be.

The water utility currently monitors blooms by relying on forecasts and by using sensors that can detect algae at its two intake pipes — but that only gives them 30 minutes to react.

“That’s not much lead time,” Bouchard said.

“It’s caught us by surprise in the past, where all of a sudden you see algae coming in and we have to react quickly,” he said.

This past summer, a blue-green algae bloom spread across the lake, producing a toxin called microcystin.

The levels were low enough that Union Water Supply’s operators could treat it by adjusting their doses of powdered activated carbon, coagulants, and chlorine.

The situation didn’t reach a crisis level, but Bouchard said the extra treatments are still complex, costly, and can cut into the supply of available drinking water.

A severe enough bloom could force a major disruption to the water supply, as it did in Quebec’s eastern townships this summer, compromising the tap water for thousands of people.

To avoid that kind of worst case scenario, Bouchard decided to invest in RAEON’s project.

“We thought it would be best to get ahead of it,” Bouchard said.

Bouchard said that while blue-green blooms tend to form more often on the U.S. side of Lake Erie, all it takes is a switch in the wind direction for the problem to end up on his doorstep.

The early warning system would be a major improvement on the current 30 minute window operators have to adapt — giving them as much as 12 hours advance notice of an incoming bloom.

That would give operators a critical window to adapt their treatment process or even shut off an intake valve to prevent toxins from infiltrating the system.

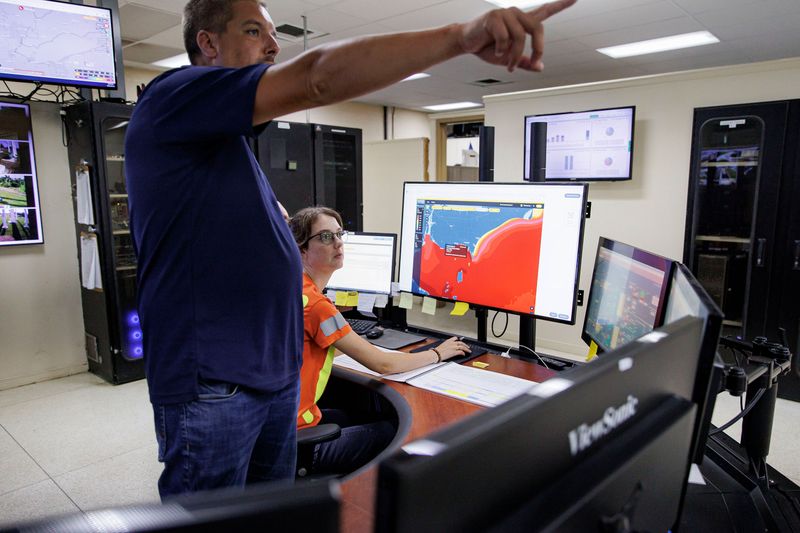

In the control room, water utility operators pull up an interactive map of Lake Erie on a large monitor.

It’s a demonstration of how the early warning system could work, once it’s up and running by the end of the year.

The map shows Lake Erie’s water conditions, measured by the buoys every 10 to 30 minutes. In early August, the monitor revealed the water temperature was a balmy 27 C.

The water utility is also planning $130 million worth of upgrades over the next five years to adapt treatments to mounting threats including algae, and to meet increasing demands from the expanding greenhouse industry.

One of the four clarifying domes has been retrofitted to treat algae using a dissolved air flotation system and powdered activated carbon.

The three other clarifiers are slated to be retrofitted in the same way and a new 30 million litre reservoir will more than double the plant’s capacity by 2026.

It’s not just the Kingsville treatment centre that’s looking to adapt.

Robert Halle, executive director of the Canadian Water and Wastewater Association, said municipal water utilities across the country need provincial and federal support as they work to address pollutants like harmful algal blooms.

“Warmer temperatures accelerate and exacerbate the algal growth posing a serious threat to our drinking water supply,” he said.

Why the blooms keep coming back

Back on the boat on Lake Erie, Environment and Climate Change Canada scientist Daryl McGoldrick discussed the challenges of monitoring algal blooms — and their causes.

McGoldrick’s team investigates contaminants across the Great Lakes, including the resurgence of blooms in recent decades.

“It’s a really open area of research,” he said.

Harmful algal blooms used to be common in Lake Erie in the 1950s and 60s. In the 1970s, the situation improved after the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement limited phosphorus and other pollutants from entering the watershed.

But since the 2000s the blooms have cropped back up.

Oceanographer Richard Stumpf, who speaks for the U.S. scientific agency NOAA, said blue-green algae blooms used to peak quickly and die off in Lake Erie, but now the peaks happen several weeks earlier than they used to, typically spanning from early August to September.

In the 2024 season, the bloom started on June 24, the earliest one has ever been detected since NOAA started monitoring in 2002. It reached up to 1,700 square kilometres at its peak in August, extending through September and dwindling in October.

Stumpf said their current understanding is that while municipal sewage runoff was the main culprit of the Lake Erie blooms pre-1970s, agricultural runoff is now the more significant contributor.

The primary source of phosphorus in Lake Erie is the Maumee River, on the U.S. side.

But smaller waterways contribute too.

McGoldrick pointed to Sturgeon Creek, which flows through Leamington and runs past greenhouses, farmers’ fields, commerce and industry, carrying with it polluted runoff.

“Tributaries like this one around the whole basin of Lake Erie are the main source for nutrients to the lake that cause the algal blooms,” McGoldrick said.

Other influences including climate change, Stumpf said, aren’t likely to help.

“The jury is out on whether climate change is changing the blooms [in Lake Erie],” he said. “But the sorts of things that climate change is likely to cause have the potential of making the blooms worse.”

Across Canada, and the world, climate change is expected to contribute to bloom-friendly conditions: warming temperatures, more intense heavy rains increasing polluted runoff, and changes in wind patterns.

Despite NOAA’s records showing earlier and longer blooms, there are various ways of measuring what makes a bloom worse. Research scientists with Environment and Climate Change Canada said they have not detected significant increases in their Lake Erie bloom metrics, though they said severe blooms remain a recurring problem.

Understanding long-term bloom trends — and the combination of factors influencing them — is exactly why McGoldrick and Fisk say their field research is vital.

“When the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement was signed in the 70s, the lakes were in really bad shape and it’s been a monumental effort by all of the parties and partners and lakes to get to where we are now,” McGoldrick said.

While the state of the lakes have generally improved, McGoldrick said new issues are emerging and it’s not limited to toxic algae — invasive species, climate change and shifts in the ecosystems.

“Some of these things are starting to crop back up … so really now the focus is trying to understand what exactly is causing that and then trying to find new ways to reduce them.”

While the data gathered by the buoys feeds that research in the long-term, they will also help protect the drinking water supply in the short-term.

If successful, the early warning system could serve as a model for other water utilities across the country as municipalities look for ways to adapt.

Fisk said he hopes his work raises awareness around why water should never be taken for granted, even in the Great Lakes, the largest fresh surface-water system on Earth.

MORE

Footer Links

My Account

Contact CBC

- Submit Feedback

- Help Centre

- Audience Relations, CBC

P.O. Box 500 Station A

Toronto, ON

Canada, M5W 1E6 - Audience Relations, CBC

Toll-free (Canada only):

1-866-306-4636 - TTY/Teletype writer:

1-866-220-6045

Services

Accessibility

- It is a priority for CBC to create a website that is accessible to all Canadians including people with visual, hearing, motor and cognitive challenges.

- Closed Captioning and Described Video is available for many CBC shows offered on CBC Gem.

- About CBC Accessibility

- Accessibility Feedback