November 11, 2019

CBC Saskatchewan, CBC Manitoba and CBC North embarked on a months-long project to speak with elders, elders-in-training and youth from across their vast territories to learn how these knowledge keepers view their role today — and why they're more critical than ever before.

Read other stories from the Walking With Elders series.

On a sunny day under a canopy of soaring evergreens, Annie Natomagan, a 75-year-old, Cree elder, is surrounded by children. Their moonya (white) teacher has brought them to meet Natomagan, who is teaching them how to prepare wild meat.

As the group waits for buckets of fresh catch from Saskatchewan's Pinehouse Lake to be brought to them, they study dozens of frozen ducks. It's a mess of twisted, feathered limbs and wayward beaks and feet.

"When you look at it every day, you'll get the hang of it," Natomagan said.

She's been doing this work since she was six, and now, she's demonstrating for kids the same age.

In front of her audience, she moves with grace and grit. She ignores the eruption of horseplay that spills out as the birds' frozen bodies are dumped onto a table. The children watch her mastery with fascination.

As the children wait for the fish to come, they begin to sing in Cree. A small smile transforms Elder Annie's stern concentration.

Her philosophy is children see, children do.

"I want the parents to teach their children to do everything the old way — even to tell them the way to wash their clothes. I've got scrub boards at the cabin," she said, smirking.

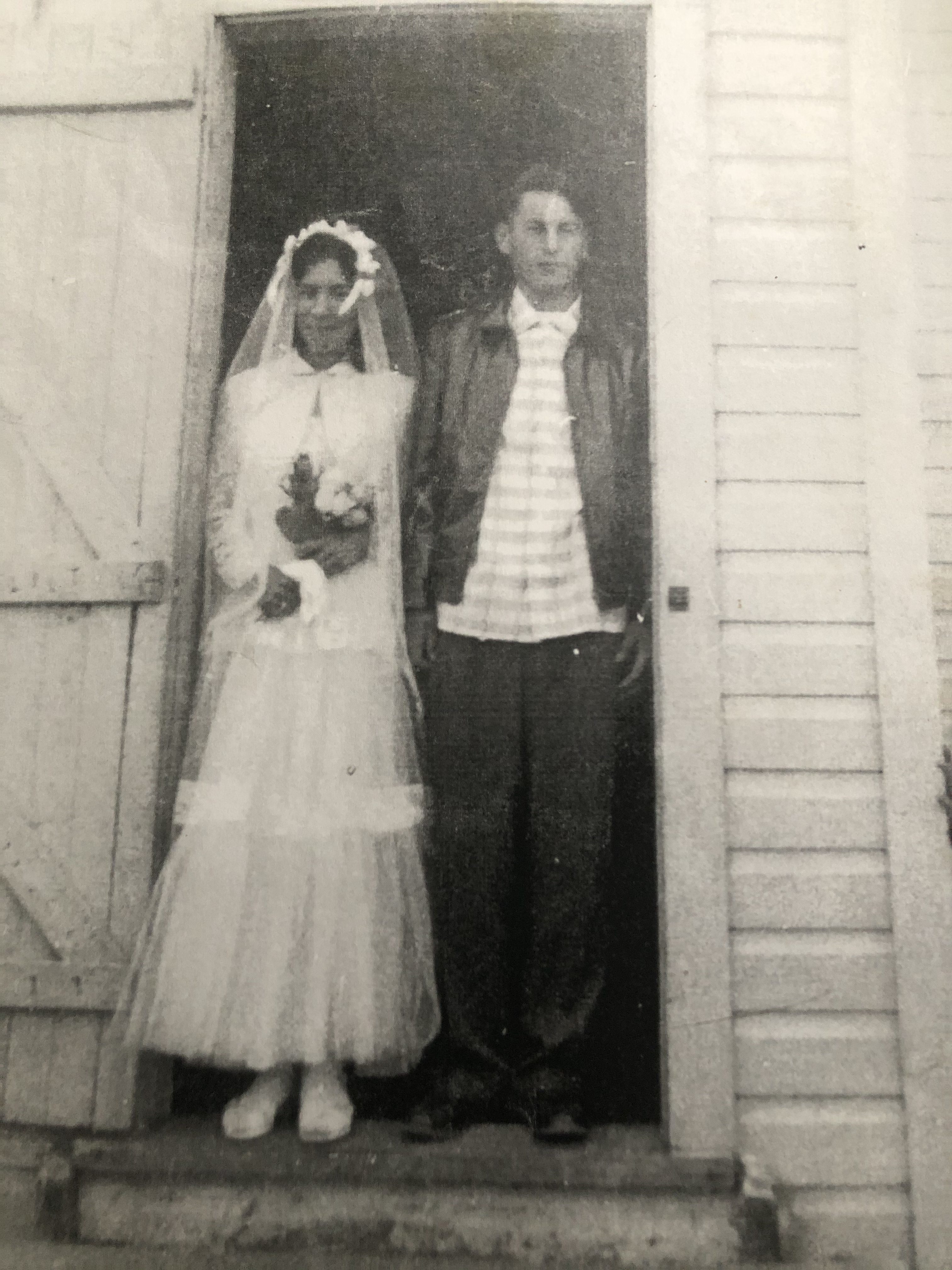

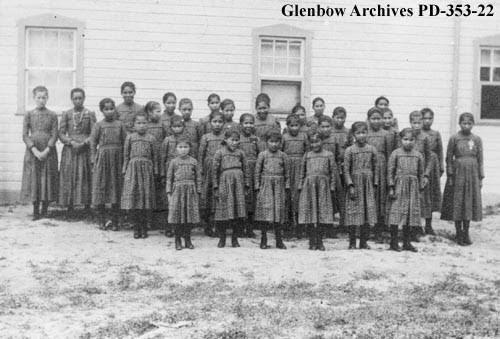

For her, the skills these modern kids need to survive are the same ones that helped her survive everything from residential school in the 1950s to the births of her 13 children, the miscarriage of one, and then the death of two, as well as nearly 60 years of marriage. The old ways: speaking Cree and living off the land.

"I think it would be nice if they went back ... [today] you push a button and everything comes to you," she said.

Children these days spend too much time with screens and devices, she said.

"When you see kids, some of them are too fat. They're busy on the phone, and they're unhealthy. They get sick," she said.

"Kids a long time ago, they were healthy. They didn't have too much candies. ... Then, they only drank water, and there was no tap water. The water was pure. It was clear. Nowadays, you have to boil your water."

Back to the old ways

Elder Annie was born in Pinehouse, a primarily Métis village of around 1,000 about 500 km north of Saskatoon, to parents who spent their lives tending trap lines. For two months each summer, she and her siblings would get to leave the mission school they attended and rejoin their family.

"We'd come back, we stay in the tents, we'd go out boating, canoe, me and my sisters," she recalled. "We'd help dad set the net, make fish, moose meat, dried meat — everything. Oh, we had lots of fun!"

Those precious summer memories have manifested in the lessons Elder Annie has shared with all of her children, who have, in turn, passed them on. It's a ripple effect with a reach that could easily rival that of Pinehouse Lake's 404 square kilometres.

Dreaming of a big moose

Elder Annie's grandson Jordan Smith was eager to graduate from high school. For the 20-year-old hunter, less time in a classroom meant more time in nature.

"When I got out there, it helps lots: the beauty out there, the rest, the meals."

Smith said being able to leave small village life behind to head out into the wilderness is a skill that has saved him.

"I learned a lot of stuff on my own, just by watching people. I was always around my Grandma Annie, watching her cut fish. … Both sides of the family are hunters and trappers. That's where I learned everything," he said.

In 2015, shortly after Pinehouse was evacuated because of wildfires, Smith's mother was diagnosed with Stage 5 colon cancer. She died from it a few months later.

As a grieving teen, Smith found himself drinking to cope.

"When I kept on drinking, it generated a whole lot of anger after I lost my mom. I overdid it," he said.

It would have been easy for Smith to fall prey to the trap of alcohol addiction, but his ability to hunt set him free, he said, and made him an anomaly among his peers.

"I am always out there, and I am getting better every day. I feel the healing out there," he said.

"I only see the old elders out there. I think of myself as one of the youngest that's out commercial fishing, that's out hunting. I have friends that I invite. I show them what I know. They usually kill their first [animal] when I take them out there."

Jonah Natomagan is one of those friends.

When he first came out with Smith, he brought his camera. For him, hunting for a perfect snapshot of the aurora saved him during his turbulent teen years.

But learning how to hunt to provide food for his family has strengthened Natomagan's connection to nature.

"Knowing what Jordan knows, I know we wouldn't probably have gotten this knowledge if it wasn't for an elder, somebody who went out there themselves and experienced it," he said.

While Smith teaches Natomagan how to catch wild animals, Natomagan teaches Smith how to catch the light perfectly with a camera.

Both young men plan to live in Pinehouse and feed themselves with what they hunt. They see value in Elder Annie's knowledge because they know they'll need it to continue to live the life they want.

- Colonialism has left some young Inuit in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, struggling to connect with their culture. But a group of grandmothers is fighting to change that

- Elder Yvonne Maurice knows what it's like to be bullied, to struggle with drinking and to feel alone. Now, she uses her experiences to help teens in northern Sask.

In turn, Smith plans to keep sharing the knowledge elders are passing on to him.

"I want to share it early. Even while I am learning, I want to share it,” he said.

After all, nothing beats the feeling that comes from mastering an ancient skill.

"There was many times I saw my dad bring down a moose, but my first time I was really happy," said Smith. "He passed me the gun, and I took my first shot, dropped my first moose … by the time I got into town, my grandma Annie says, 'You're a man, you're a man.' Everybody was like this. I had a lot of pride there."

Now, his best friend has big dreams, too.

"A big, Yukon bull moose would be my dream," said Natomagan. "You can shoot those here. Me and Jordan have gone out quite a few times. Didn't really have any luck, but just being out there, it was mind-blowing."

In memory of 'the queen'

After a long, busy summer in Pinehouse, Elder Annie died suddenly on the Thanksgiving long weekend during a trip to Saskatoon. The 75-year-old had a heart attack while visiting her daughter.

Before she was Elder Annie, she had been known in the village as "the queen" because of a contest she won. And in many respects, she resembled one: She was a strong leader who always cared for her people.

"My mom made a big impact in a lot of people's lives."

Her daughter, Leeann Smith, said her mother's modest home was always a welcoming place where many people came to eat.

"We don't remember ever going hungry. When my dad had to go to work in Churchill, she would get the boat ready, go set a net, get the fish, bring it, prepare it and feed us. We were always grateful. I remember she used to work her butt off, just to feed her 13-plus kids.”

Smith said she still remembers that her mother would tell them, "If you’re hungry, just remember there's always food in the bush."

She remembers being a young teen when her mother taught her how to catch and skin a rabbit. The memory stuck with her, but she never quite mastered her rabbit stew recipe.

Smith said all of her siblings use the skills their mother taught them to live today, but no one works the way her mother did.

“One whole moose, in one whole day. Who does that? I can't do that," she said of her mother's incredible ability to prepare an entire kill.

"It takes me three, four days, my husband and I put together."

Smith said her mother knew she was nearing the end of her life and called her daughter the day she died.

"I always asked her, 'Mom, do you ever get tired?' she told me, 'Yep, that's when I go to Saskatoon.'"

Now. Smith is helping her father adjust to life without his wife. The couple would have celebrated 60 years of marriage on May 30, 2020.

"My mom made a big impact in a lot of people's lives."