November 11, 2019

CBC Saskatchewan, CBC Manitoba and CBC North embarked on a months-long project to speak with elders, elders-in-training and youth from across their vast territories to learn how these knowledge keepers view their role today — and why they're more critical than ever before.

Read other stories from the Walking With Elders series.

Yvonne Maurice winced as she recalled the day, decades ago, that she was badly burned.

"I was getting wood, and at that time, there was no electricity, no running water, no nothing. I put wood in my dress, and I shoved it in the stove and my dress caught on fire," said the 72-year-old, Cree elder, who lives in Saskatchewan's north.

She had been doing chores alone with her younger sister. There was no help.

After the flames ravaged her eight-year-old body, months of brutal isolation in hospital followed.

"I never got a phone call, no visits, no nothing," she said. "And then when I came home, I started getting teased by kids because of my scars."

Maurice said this is where she believes the trouble in her life started.

The school years that followed were miserable. She dropped out at 15 to work.

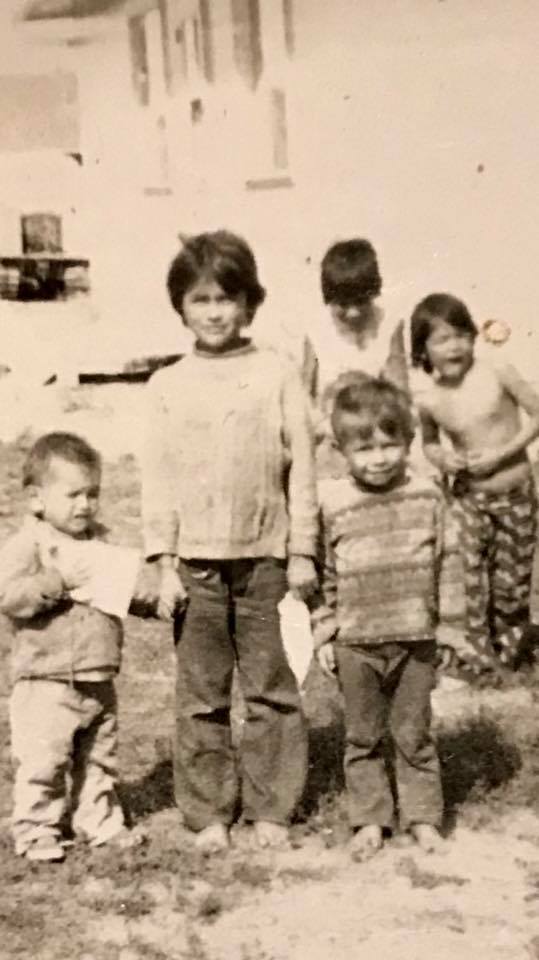

A few years later, she married Robert, a trapper from Patuanak, a village that sits on the edge of Lac Île-à-la-Crosse, nearly 200 kilometres north of her home in Pinehouse, a primarily Métis village of around 1,000 about 500 km north of Saskatoon. She spent decades hunting and trapping on the land with Robert while raising eight children.

When her kids were young, she drank. She said this remains her life's biggest regret.

"I should've stayed home and taught them everything that I know instead of drinking," she said.

The pitfalls Maurice has encountered have motivated her to ensure any teen she meets won't stumble in the same ways she did — especially in the face of bullying.

"Now, I try to make it up," she said, which means sharing her journey with children who are struggling.

Above all, be honest

Maurice has worked with children at Pinehouse's Minahik Waskahigan School for more than two decades. Her work there has ranged from being an attending officer (or "chasing after kids," as she puts it) to a school co-ordinator.

More recently, she has run sharing circles at the high school, baring her own wounds, including the 2018 suicide of her youngest son, in the hopes that her trials will help teens who are on rough journeys themselves.

- A culture not lost but disconnected: Colonialism has left some young Inuit in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, struggling to connect with their culture. But a group of grandmothers is fighting to change that

"Talk to the kids and give them your own experience," she said, explaining her approach. "I don't hide anything from them. I don't lie to them. I am open when I talk to them."

Cyberbullying is a major problem, according to a 2017 report on youth suicide in northern Saskatchewan from the province's Advocate for Children and Youth.

The report referenced a 2016 provincial survey of teens that found female students in Grades 7 to 12 were nine times more likely than boys at that age to experience cyberbullying.

As someone who was bullied herself, Maurice knows how hard it is to ignore the taunts and be resilient. "It took me a long time to accept that ... I [shouldn't] take anything seriously," she said.

The report found many bullied teens felt they had nowhere to turn for help, and identified a lack of emotional support as one reason why youth might think about or follow through with suicide.

"Many youth reported feeling invisible to their families and communities, feeling ignored at school and that losing loved ones, friends or relationships contributed to social isolation and loneliness," the report said.

Avoiding screens

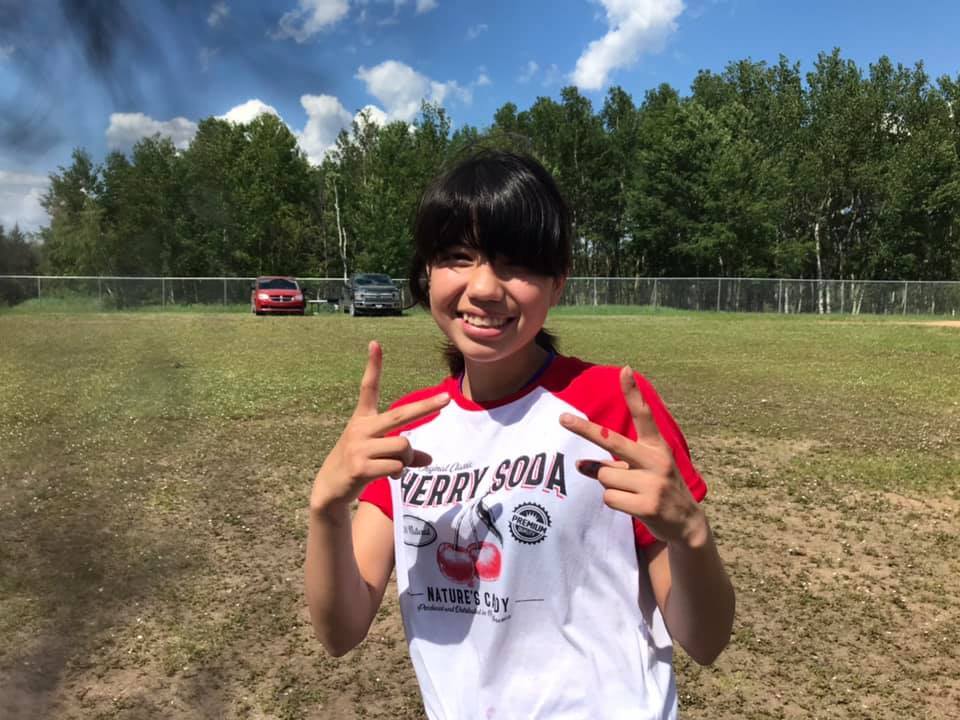

Keira Natomagan knows what that's like.

The 12-year-old said she experienced cyberbullying at her school in La Ronge, Sask. The situation got so bad that she had to move in with her grandmother in Pinehouse, where she lives now. Natomagan plans to avoid social media, saying she'd prefer to play outside.

"It's very dangerous to get Facebook [at] a young age," she said. The online taunts were hurtful, and trying to engage with bullies in a reasonable way didn't make it any better. "Talking to people on the internet doesn't actually help what they say."

Overall, she said she is more comfortable talking to people in real life.

With many teens, it's not that simple. For some, their identities and self-worth are wrapped up in a social media ecosystem that feels worlds away from the physical one.

Maurice said she sees how disconnected kids can become behind screens, because it happened with her own children. The difference is that the screen they were entranced with, growing up in the 1980s and '90s, was television.

"All of my children talk Cree, [but] the last two don't talk Cree. They understand, but they don't talk, because that's when the TV came in," she said. "So then, the TV was my babysitter."

Of all her children, Maurice said she had the least amount of time to spend with the youngest kids. As a result, a big part of their socialization was people speaking to them, in English, on TV.

Kelly Kwan is an educator in Pinehouse who sees the benefits of less screen time. He works as a Grade 9 teacher at Minahik Waskahigan School, which has a no-cellphone policy.

Although it has faced opposition, the rule is something Kwan believes is helping his students. He said since the cellphone ban, grades have improved across the board and children seem happier.

"There's laughter again in the class. There's more socializing. It's nice to see kids talking to each other, to their teachers," he said.

Kwan said identity has become a more challenging issue in the age of social media, for individuals — both young and old — and the community as a whole.

"Our elders, they've experienced so much of the change and the history from when they were kids to how the technology has come into our world, and our native country, and we have to make these adjustments, and they have to as well," Kwan said.

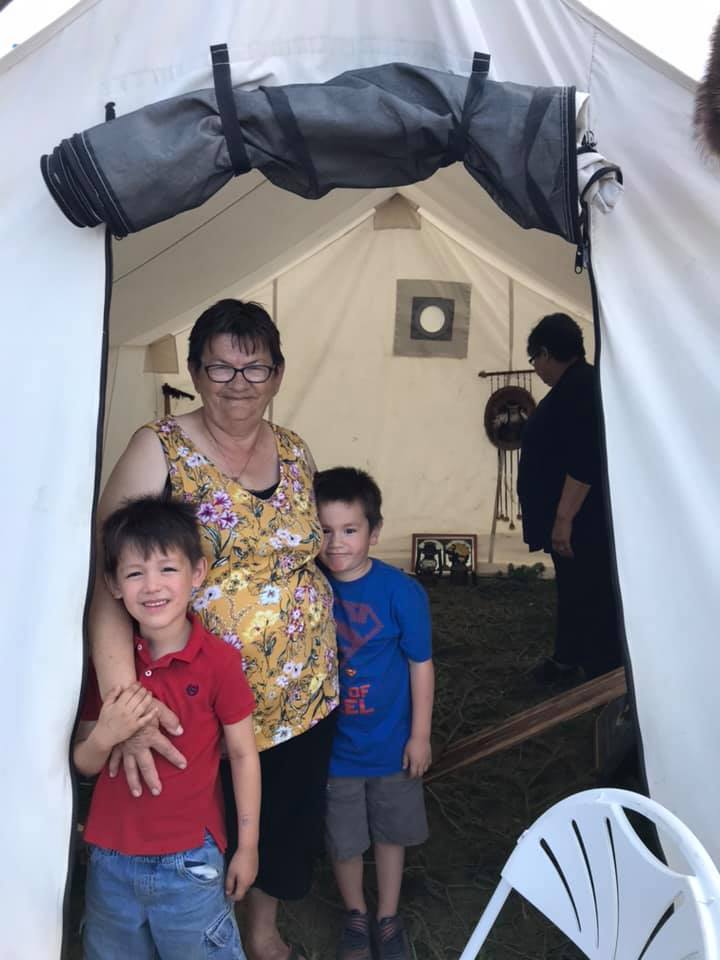

When Maurice sees young children carrying around phones, she worries it disconnects them even more from their language and culture. She hopes that by sharing her experience, including at a gathering of elders in Pinehouse this past summer that Natomagan and other school classes attended, parents will consider how much screen time their kids are getting.

After decades working with children, Maurice believes the most important thing an adult can do to help them is to include them and talk to them.

"No matter what you do, even if you're cutting wood, try to explain to the kids how you do that," Maurice said. "The kids are in the dark if you don't teach them nothing. Sit down and talk with your kids and explain things to your kids, even suicide — anything."