July 17, 2021

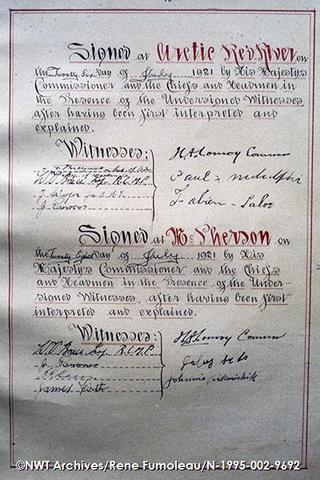

One hundred years ago, Paul Andrew’s relatives were travelling along the banks of the Keele River in the N.W.T.’s western mountains when they came across a wooden post, inscribed with news that a treaty had been reached.

That was the first time they heard of Treaty 11, which defined a new relationship between the Crown and Andrew’s people.

They were later told the treaty was for peace and friendship. The Crown would respect the traditional Dene way of life and provide education, healthcare and housing. For their part the Dene agreed to let settlers move through the land peacefully, so long as their work “does not interfere” with their traditional way of life.

“The unfortunate part is, we trusted [the settlers],” Andrew said. “Our elders trusted them.”

The ratification of Treaty 11 affected Dene life in ways still felt today.

Made homeless on their own land

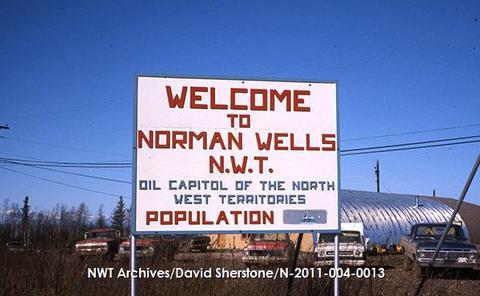

It was the discovery of oil in 1920 near Norman Wells that awakened the Crown’s interest in a treaty with Indigenous people of the Northwest Territories.

The Blondins lived, hunted and survived for generations on that land in their traditional territory. They used a special yellow-brown substance seeping through the water at a nearby creek to grease their dog sled runners in the spring, and waterproof canoes in the summer.

Scottish explorer Alexander Mackenzie saw the same substance during his 1789 voyage down the Deh Cho River, which was later named after him. He recognized it for what it was — bitumen.

The Blondins continued to use their oil resources for 200 years after Mackenzie’s discovery without any disturbance.

By 1914, things started to change.

Uninvited by the family, biologist T.O. Boswell staked three claims on Blondin land and named a nearby creek after himself.

Imperial Oil bought Boswell’s stakes in 1919. That summer, the company brought a rig, a crew of workers and an ox to the creek to start exploration.

While the Blondins visited relatives on Great Bear Lake, the crew took over the family’s three log cabins and warehouse, according to written testimony* by Walter Blondin.

Blondin wrote that Imperial Oil staff drove the family out of their homes when they returned, saying they were no longer welcome on their traditional lands.

Raymond Yakeleya, a descendant of the Blondin family, said it was the beginning of a very hard time for his relatives.

“They had nothing, they were homeless,” he said. “We’d never seen the invasion of the white man, taking over people’s homes.”

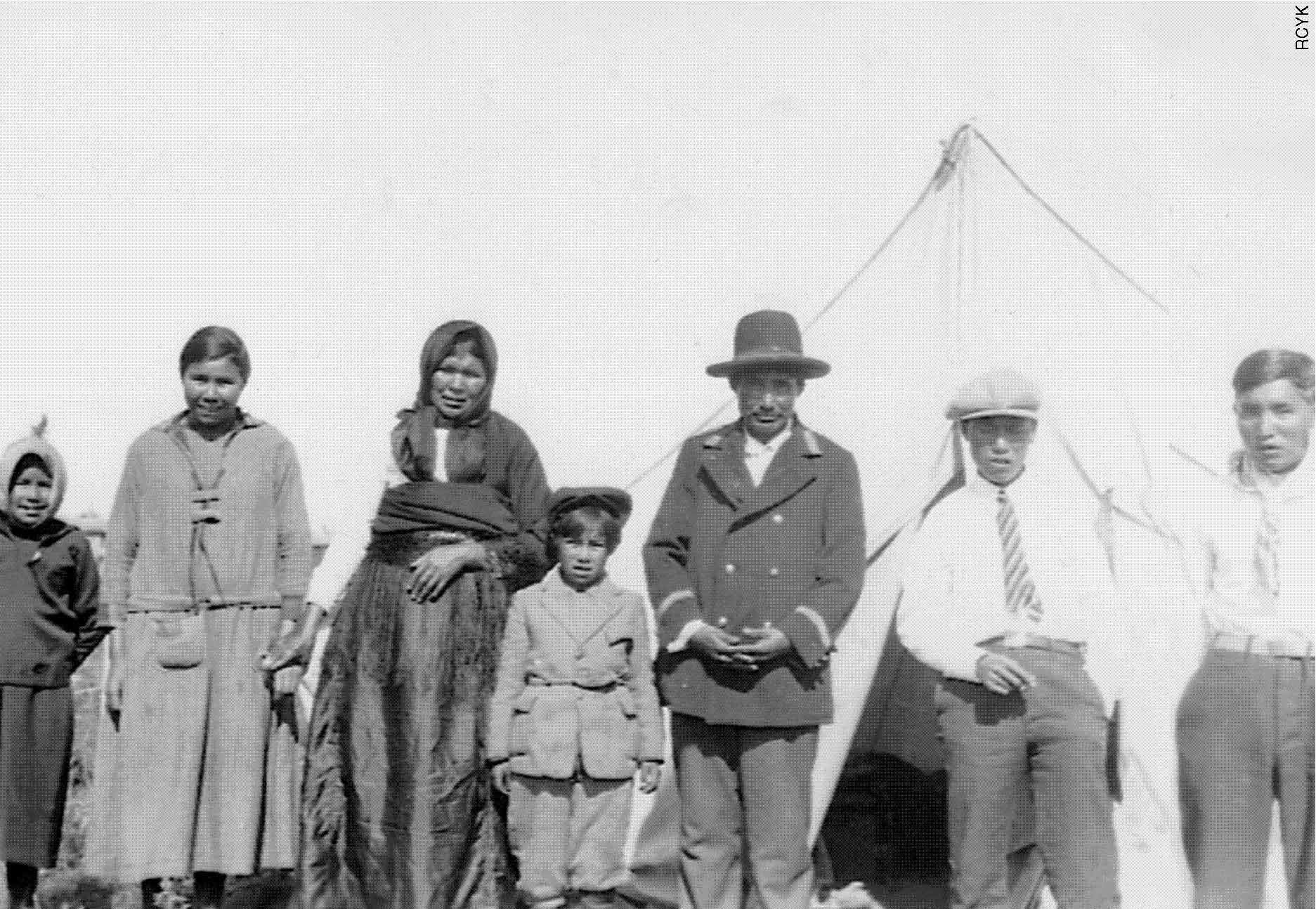

The family moved 50 kilometres south to Fort Norman, now Tulita, where they lived in tents.

So when settlers arrived with Treaty 11 in hand two years later, Yakeleya said they were not well received.

“The first thing that the people [wanted to] know was ‘What the hell are they bothering us for now?’” Yakeleya said.

Zaul Blondin, the appointed chief, did not want to sign the Treaty but was persuaded to by the Roman Catholic Church’s representative, Bishop Gabriel Breynat.

Signing Treaty 11 emboldened the oil company. A few winters later, the company demolished the Blondin’s homes, throwing the remains, with all their family possessions, over the riverbank, Yakeleya said.

The Blondins never lived on their ancestral land again.

Now, their descendants are calling for an apology for the way Imperial Oil, and the Crown, irrevocably changed their lives.

“It needs to happen, and it's going to happen,” Yakeleya said.

When contacted for comment, Imperial Oil directed the CBC to an article written on Imperial Oil’s website to celebrate their 100 years in operation. It does not specifically mention the Blondin family, nor the signing of Treaty 11.

A paragraph at the end notes the company’s relationship with Indigenous peoples “remains strong” after 100 years and often goes “far beyond business.”

Hunting on hold

John T’seleie used to watch his parents hide every waterfowl they harvested in Fort Good Hope, N.W.T.

They were protecting themselves from game wardens, who came to signatory communities to tell land users what they could and could not hunt.

“It … made life very difficult,” T’seleie said. “[They had a] fear of going to court or jail because of it.”

The Dene were concerned that signing Treaty 11 would mean game rules might be imposed on them, because that’s what happened to those who signed Treaty 8 several years before, according to Yakeleya.

“When they asked commissioner [Henry] Conroy about ‘can we use any animal we hunt’ and he said ‘yes you can hunt any animal,’” Yakeleya said.

“He lied to us from the very beginning.”

Yakeleya maintains that the 100th anniversary of Treaty 11 is nothing to celebrate today.

"What the hell is there to celebrate?" he said. "Nothing [but] bullshit lies, fraud, theft, embezzlement."

The written version of Treaty 11 gives Indigenous peoples the right to “pursue their usual vocations of hunting, trapping and fishing,” with some regulation — a caveat not explained to its signatories at the time.

Unbeknownst to the Dene, Canada had also signed the 1917 Migratory Bird Act, a deal with the United States and Mexico to protect migratory birds, their eggs and nests from destruction.

What that looked like in Tsiigehtchic, according to Lawrence Norbert, a descendant of treaty signatory Paul Niditchie, was that important sources of food, like ducks, could only be hunted a few times a year.

“There [were] just … more and more regulations you had to live by,” Norbert said.

“But I think what really bothered them was that they had no input into these regulations. It was … mostly white people telling them well, you can’t do these things.”

Authorities occasionally made arrests for breaches of the act. One infamous case is that of Yellowknife hunter Michel Sikyea, who was charged after shooting a duck out of season in 1962.

It wasn’t long until the game wardens extended their quotas to mammals too, like beavers and moose.

These quotas stayed in place long enough for T’seleie to remember how they regulated beaver trade in the 1950s.

“They used to issue … tags, little pieces of metal,” he said.

“Each adult was allowed only a certain number … and every [beaver] pelt traded at the Hudson’s Bay had to have this metal tag on it.”

Elsewhere, game wardens would say people could only hunt one moose per year, something Yakeleya said wasn’t “feasible” for his people.

All of these hunting quotas should be considered treaty violations, as far as T’seleie is concerned.

Livelihoods threatened

Elders say most mountain Dene and Gwich'in (the most northern Dene of North America) carried on their traditional lifestyles after the treaty was signed, despite the disruptions they started to see in their lives.

The promises made by Canada were only observed on Treaty Day, Norbert said, when everyone received their annual payments.

“It was a celebration,” Norbert said. “The Gwich’in [expressed] that they … intended to keep their side of the bargain.”

Between the 1930s to 1960s, white settlers flocked to the territory to work at the newly developed Giant Mine project outside Yellowknife. Others descended on the shores of Great Bear Lake in Deline, searching for radium. It was also a time during which Canada's notorious residential school system expanded its reach in the territory.

People started to ask why settlers were able to run these projects on their land, without asking them first or respecting their Treaty-guaranteed rights.

By the 1970s, the expansion of these projects started to directly threaten livelihoods. Paul Andrew, then a young N.W.T. government worker in Tulita, fielded many complaints about it at the time.

“I’d get people coming into the office saying some oil company ran over my trapline, what’s going on?,” he said. “We [found] out … someone in Yellowknife granted them permission and so we’d say, why? You can’t do that.

“They said, ‘yes we can, this is Canadian land.’”

The Dene and Gwich’in asked to see the written version of the treaty. When it was given to them, almost fifty years after its original signing, people were shocked at the terms they had unknowingly agreed to.

The Treaty forced the signatories to “cede, release, surrender, and yield” all of their land rights to the Dominion of Canada. In return, the “headman” would get a larger sum of money than other signatories.

In Fort Norman, chiefs were paid $50 and everyone else got $12. The next year, recollections from elders in Yakeleya’s book, We Remember the Coming of the White man*, say the payments whittled down to $5 each.

“Who in their right mind would give up land for five dollars a year?,” Andrew said.

But the treaty party never talked about land secession, according to descendents and testimony from Tsiighetchic elders in the book, Gwichya Gwich'in Googwandak.

“It is clear that this consequence of signing the treaty was never explained to the Gwichya Gwich'in, neither on July 26, 1921, nor at any time thereafter,” an excerpt from the book reads.

At the next regional assembly, Andrew said there was one unanimous message: there needs to be a new relationship with Canada.

They tried through conversation first, to no avail. Then, they took it to court.

“People were saying ‘enough is enough,’” Norbert said. “We’re going to give Canada a reminder that they’re not living up to their obligations.”

In 1973, Francois Paulette, chief of Smith’s Landing First Nation in Fort Smith, filed a caveat to the N.W.T. Supreme Court. He and 16 other chiefs wanted to legally gain back the land lost to Treaties 8 and 11.

Justice William Morrow held six weeks of hearings across the territory to figure out whether signatories understood the treaty’s terms. He ruled they did not, although the case was later overturned on a technicality.

Many credit this case as the first step toward a modern relationship with Canada, one that is still playing out today.

A new relationship

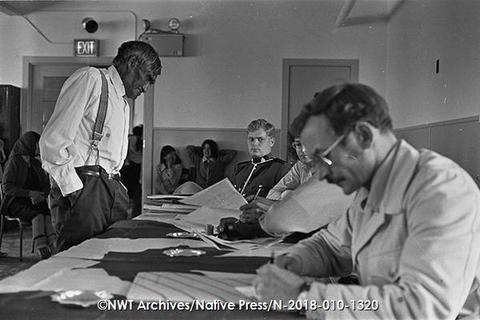

![Voting at the Dene National Assembly in 1978 in Tulita. Caroline Moses, Andre Jerome, Jonny Charlie, Nap Norbert, Charles Koe, Caroline Carmichael, Morris Cardinal, Ruth Furlong, [First name unknown] Veneltsi, Art Furlong, Raymond Yakeleya, Morris Blake, William Greenland, Mary Kendi, Barney Natsi. (NWT Archives/Rene Fumoleau fonds/N-1998-051: 1625)](https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/craft-assets/images/N-1998-051-1625_141.jpg)

Indigenous leaders in the N.W.T. continue the work of their ancestors, using the Treaty that deceived them as the backbone for a new nation-to-nation relationship with Ottawa.

Treaty 11, although misleading, did protect hunting, fishing and trapping rights on paper. In 1982, Section 35 of Canada’s newly repatriated Constitution codified these rights.

With it came a new era of negotiations in the Northwest Territories.

Between the mid-1990s to early 2000s, the Dene of the Sahtu, Gwich'in and Tlicho regions signed major land claim agreements with the federal government. These agreements include provisions that let Indigenous peoples own and co-manage their land and resources.

Other groups are still negotiating their own self-government agreements.

Ken Kyikavichik’s great-grandfather, Chief Johnny Kaye (Kyikavichik) Sr., signed the treaty on behalf of the Tetlit Gwich’in in Fort McPherson.

He’s taken on some of that work now, as chief of the Gwich’in Tribal Council.

The Gwich’in have been negotiating their self-government agreement for 24 years, Kyikavichik said, but they will keep going until they get it right.

“Fundamentally my job … is to ensure the rights and interests of our people are always protected, and we’re not signing away unduly any rights that we have today,” he said.

Even agreements signed long ago will take whole lifetimes to implement, according to John B. Zoe, advisor for the Tlicho government.

Zoe said communities need to invest in building the capacity of their young people, so they can keep doing the work started long before them.

“We need … our own young people to start training in management, in political science … be teachers and get into financing,” Zoe said.

“But at the same time, pushing your own relationship to your own land, language, culture and way of life.”

To Norbert, this new generation of Indigenous leaders is promising.

“I have a dream that one day we will have a Gwich’in government that’s no longer under the Indian Act,” he said.

“That we can make our own decisions about what happens on our own land, and within our own communities.”

*Stewart, Sarah, and Raymond Yakeleya, eds., We Remember the Coming of the White Man: Special Edition in Recognition of the 100th Anniversary of the Signing of Treaty 11. Calgary: DURVILE & UpRoute Books, 2021.

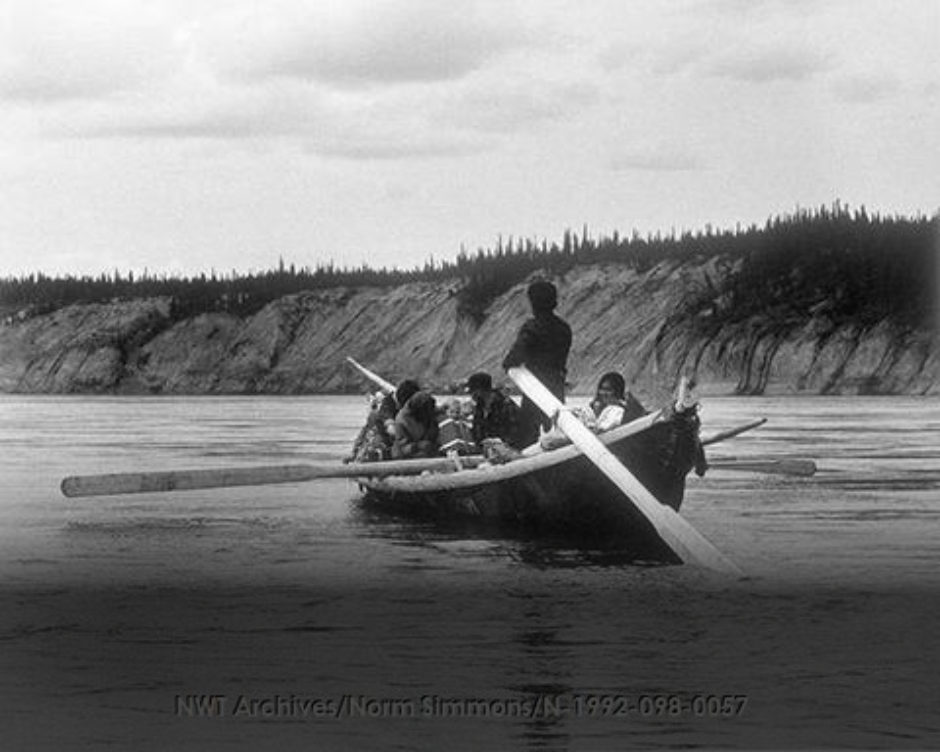

Main image: Moose skin boat on the Keele River, 1968. (NWT Archives/Norm Simmons fonds/N-1992-098: 0057)

Note: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Jonn T'Seleie's name and the date of Alexander Mackenzie's voyage down the Dehcho (it was 1789, not 1787).