June 21, 2021

This summer will mark 100 years since a treaty party traveled up the Mackenzie River signing the last of Canada’s numbered treaties with the Dene, Tłı̨chǫ and Gwich’in communities of the N.W.T.

While communities across the territory will be marking the occasion with anniversary celebrations this summer, many others see the centenary as a moment for reflection on Canada’s broken promises to Indigenous people.

CBC North will be carrying coverage of those events and more on the legacy of Treaty 11 over the coming weeks.

In the buggy backcountry of the Northwest Territories in the summer of 1920, not far from what was then called Fort Norman, a group of Canadian prospectors squatted on unceded Indigenous land.

For some time already, they had been searching for oil first spotted oozing from the earth by the explorer Alexander Mackenzie some 150 years before.

On Aug. 25, they struck it rich — for 10 straight minutes, oil spouted 23 metres in the air, pouring an estimated 600 barrels onto the surrounding earth.

This discovery in the summer of 1920, and the “exploration mania” that followed, was the genesis of Treaty 11, the last of Canada’s numbered treaties, for Canada and its government.

Treaty 11 territory encompasses more than a dozen Gwich’in, Sahtu Dene, Dehcho Dene and Tłı̨chǫ communities in the Northwest Territories — spanning an area twice the size of Germany.

But it would be decades after it was signed before northern Indigenous people would see the government’s version of the treaty, which included words they never agreed to.

It would be even longer before judges acknowledged the truth of elders’ testimony regarding the treaty — that no land was ceded — empowering a modern treaty process that’s still underway.

As communities across the N.W.T. prepare to acknowledge 100 years since its signing, Treaty 11 and its story stands as a testament to the Canadian government’s covetousness, paternalism and disregard for northern Indigenous people.

But equally, Treaty 11 is an important agreement — one intended to establish for all time the friendship and interdependence of Indigenous and settler communities in the North.

“Treaty 11 is a sacred document not to be touched, to be protected [for] our elders who made that treaty,” said Dene National Chief Norman Yakeleya.

“This is our path to self-determination, and [to] reconcile with Canada the wrongs of the past.”

SETTLERS ENCROACHING

In the years leading up to the discovery at Fort Norman, the people of the North were facing unprecedented pressure on their way of life.

Since 1900, when Treaty 8 was signed by communities in the southeastern part of the territory, hundreds of white settlers had poured into the North, chasing first gold, then furs, then oil.

These settlers didn’t consider their impact on the land and animals. They laced traplines with poison and over-hunted game to the point where, in 1910, the caribou failed to pass by Fort Rae (today’s Behchokǫ̀) for the first time in 42 years.

These changes alarmed leaders in Treaty 8 territory, who led a boycott of treaty payments in 1916 and again in 1920 over the government’s failure to protect them from white encroachment.

Disease, imported by the settlers, was also running rampant. A plague killed 70 of 600 people in Fort Rae in 1910. Waves of smallpox, influenza and measles decimated small communities.

While the Indigenous population of the Northwest Territories was estimated at more than 5,200 in 1913, by 1919, it was just 3,700.

In his seminal work on the history of Treaty 8 and 11, Rene Fumoleau, a Roman Catholic priest and northern historian, documents how these conditions concerned local colonial officials.

When Henry A. Conroy, then a “treaty inspector,” traveled the non-treaty regions of the Mackenzie Valley, Fumoleau writes, “everywhere he went he found destitution, starvation, and sickness.”

It was those conditions that led Conroy, in 1907, to write to the Department of Indian Affairs pleading that a treaty be made with the Dene.

A DISINTERESTED GOVERNMENT

For Conroy, an agreement would make clear Canada’s responsibility to offer relief to northern Indigenous people whose way of life had been disrupted by white settlement.

But Canada had its own list of reasons to seek a treaty, and few could be found in the North.

For Sir John A. MacDonald, Canada’s first prime minister, it mattered more that the Indigenous people of the Northwest were “held down with a firm hand until the country is overrun, owned and operated by White settlers.”

“The expected solution of the Indian problem was the gradual disappearance of the Indians themselves,” Fumoleau writes. “This was indeed the situation in the Northwest Territories by the turn of the century.”

But the discovery of oil in the summer of 1920 changed everything.

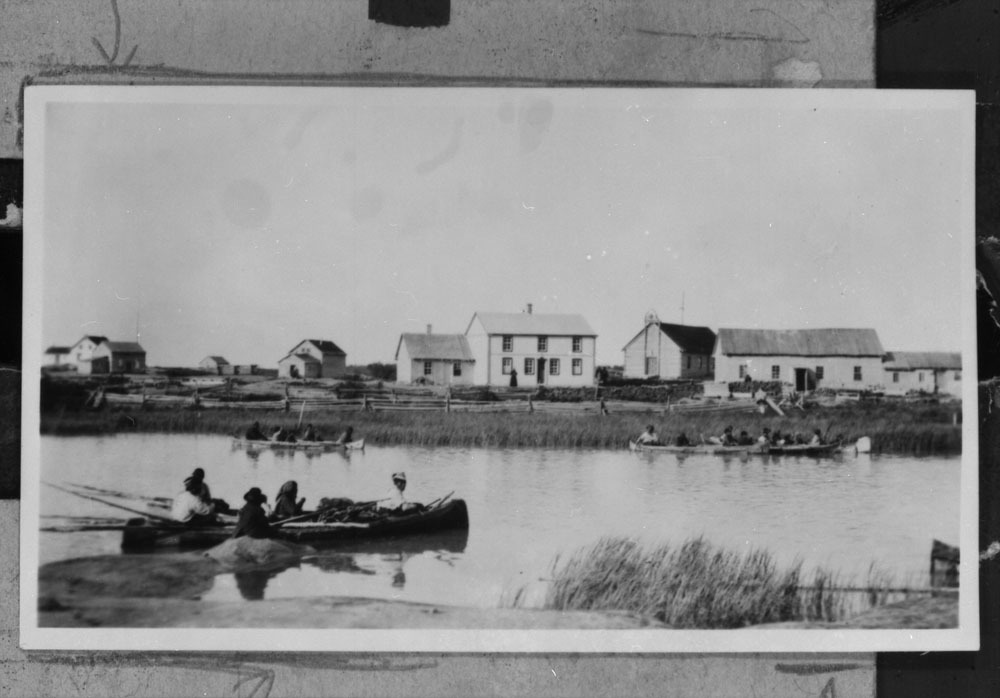

A rush of speculators — first dozens, then hundreds — made the journey down the Mackenzie River. Oil leases on unceded land were sold, and a territorial government was established to offer assistance to would-be prospectors.

“The necessity for a treaty … was [never] considered by the territorial administration,” Fumoleau writes. “It was as though the Indians had ceased to exist.”

These developments were alarming for Conroy, who had pushed almost annually for a treaty in missives to the Department of Indian Affairs.

“The rapid and unprecedented encroachment of white people means that the Indians, unless protected, will be robbed of their fair share of the best land,” he wrote in October 1920.

To his latest plea, Conroy attached a map of a possible Treaty 11 territory that extended to the shores of the Arctic Ocean, incorporating the traditional lands of Gwich’in and Inuit alongside the Dene.

That territory encompassed one of the world’s largest reserves of oil. It was enough to pique the government’s interest.

In the words of Tłı̨chǫ Elder James Wah-Shee, “the treaty was signed when it was discovered that our land was more valuable than our friendship.”

THE FLYING BISHOP

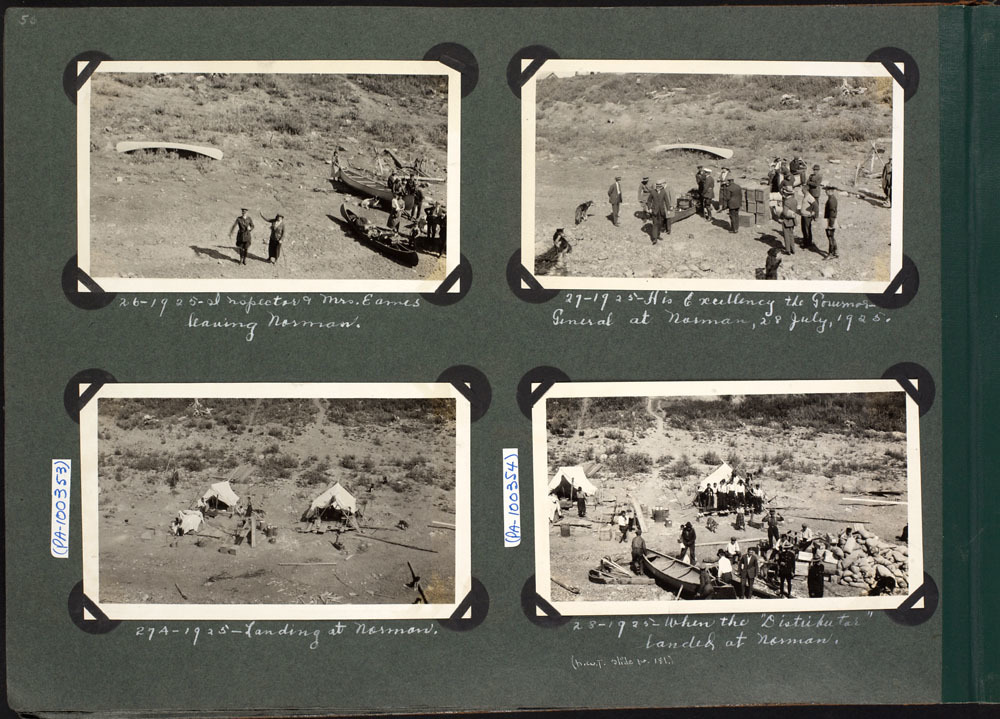

Conroy was given instructions to assemble a treaty party and travel the Mackenzie River collecting signatures in the summer of 1921.

But from the outset, this was no ordinary treaty. The text was drafted entirely in Ottawa, and Conroy was told in no uncertain terms that “no outside promises should be made” during the signing.

“The entire process actually involved little, if any, negotiation,” wrote historians Kenneth Coates and William Morrison in a 1986 research paper on Treaty 11 for the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs. “The federal government … proceeded with Treaty Eleven in a particularly single-minded fashion.”

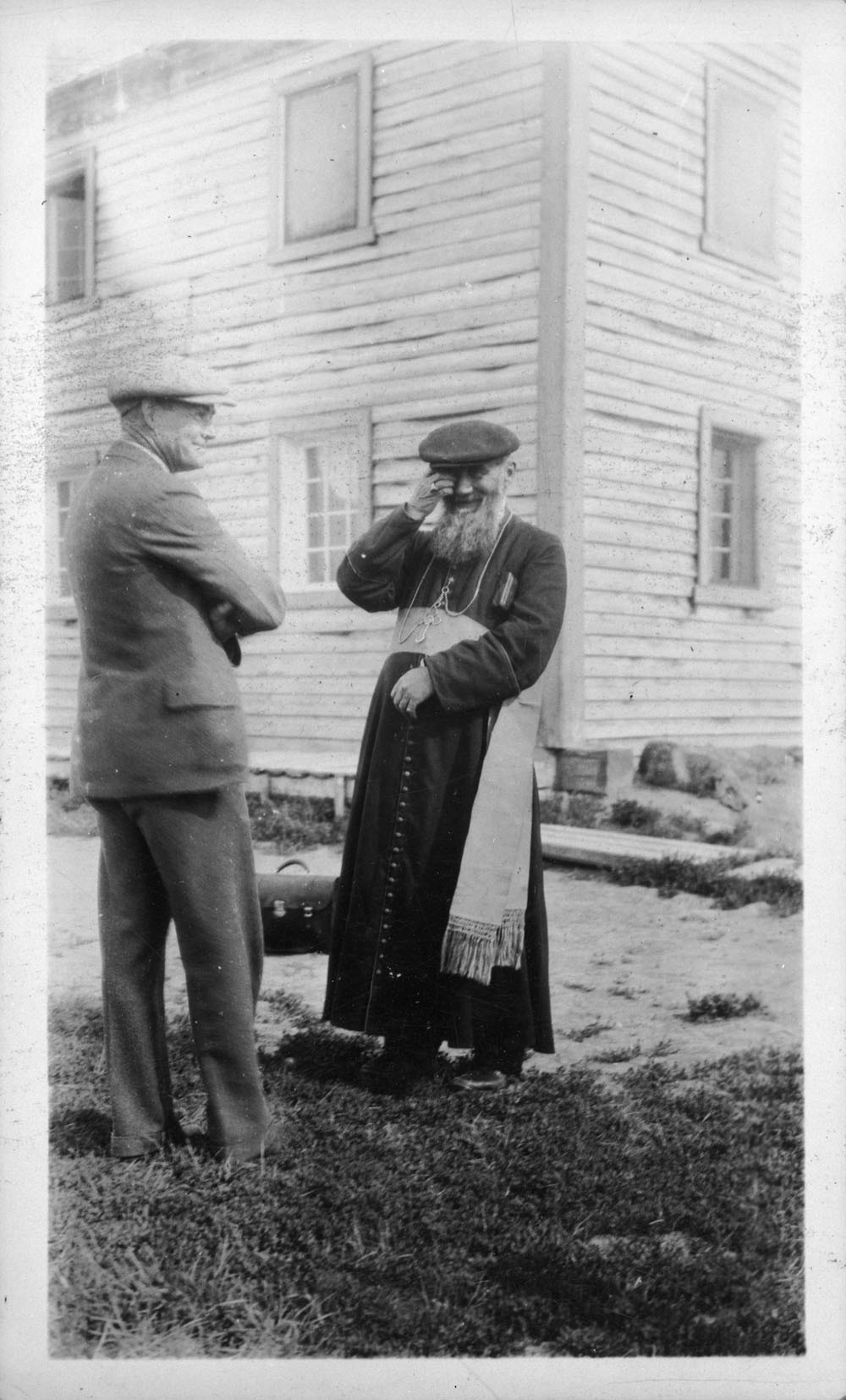

To win over the people, Conroy was given the assistance of the “Flying Bishop” of the Mackenzie, Gabriel Breynat.

Breynat earned his fame during the negotiations of Treaty 8 at the turn of the century. Well-known and trusted throughout his vast diocese, he was key in securing the signatures of chiefs, vouching for the promises of treaty commissioners that would later go unfulfilled.

“The Indian people respected and trusted the missionary,” writes Fumoleau, who is generally sympathetic to Breynat. “To what extent this influence bordered on control, or remained in the realm of guidance and advice, is a question that could only be answered by [those] who were present for the signing of the treaty.”

Since at least 1909, Breynat had joined Conroy in pressuring the federal government for a treaty in the Mackenzie Valley, hoping, in part, that it would bring relief to those dying of famine and disease.

“Conroy and Breynat, both committed to assisting the Native people of the Mackenzie, demonstrated the paternalism typical of the day,” Coates and Morrison write. “They ‘knew’ what was best for the Native people and … used what tactics were required to secure their signatures.”

But Breynat had other motives for joining the signing party in the spring of 1921.

A 1996 research paper on Treaty 11 produced by Rene Lamothe for the Dene Nation and the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples ties Breynat’s advocacy to the obvious financial benefits for the diocese, which owned churches and residential schools in the region.

Breynat’s school in Treaty 8 territory was given $72 per pupil, per year — more than 12 times what a child’s family would receive in treaty payments each year.

In accepting the offer in the spring of 1921, Breynat himself said he was swayed by the promise of free travel through his diocese, and flattered by the role he could play.

“My signature will be seen forever, together with those of our great chiefs,” he wrote, “to bear witness, for future generations, to the good faith of the contracting parties.”

A COLD RECEPTION

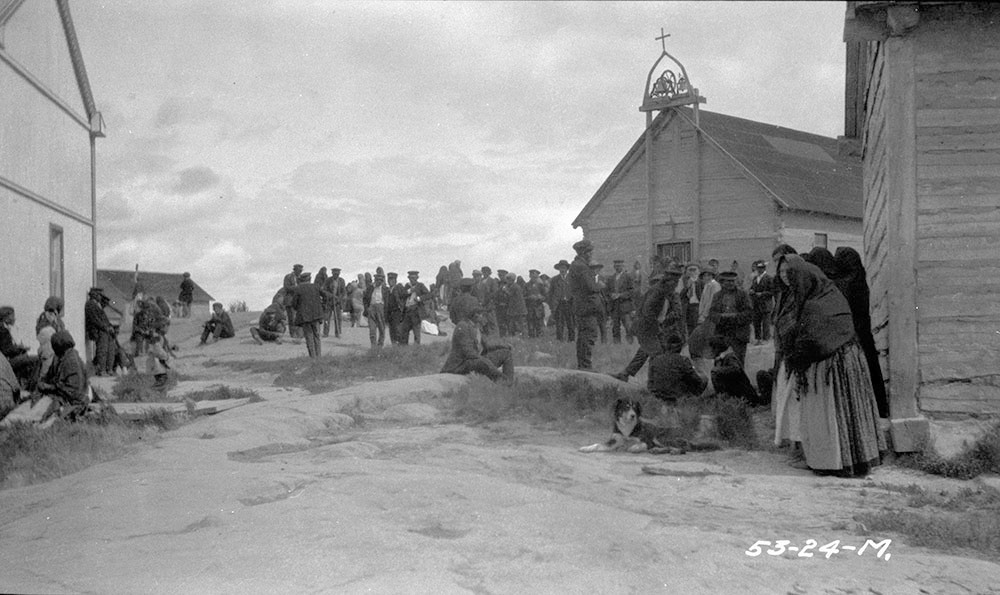

The treaty party arrived in Fort Providence, its first stop, on June 24, 1921. There Conroy met not people desperate to make a treaty but a community deeply wary of the commissioners.

Many Dene communities did not have chiefs before the treaty, but the man elected to speak at Fort Providence was Paul Lefoin, a skilled hunter known for his generosity.

Lefoin refused to even touch the pencil used for signing until, after three days, Conroy had promised hunting and fishing rights would be respected, and Breynat had offered his assurance.

In Fort Simpson, which signed July 11, the story is repeated. The Dene had “no desire to accept the treaty,” the Catholic mission records. The first chief, Ehtsieh Norwegian, could not be swayed. When he leaves, the elder Nakehk’o is convinced to sign on behalf of the community.

“A great many things were promised,” Baptiste Norwegian told Fumoleau. But Coates and Morrison write that Breynat’s and Conroy’s promises were “couched in language sufficiently vague to leave the matter subject to misinterpretation.”

“If I could just get them to be more specific about what they mean," Norwegian is said to have said, before breaking off negotiations altogether.

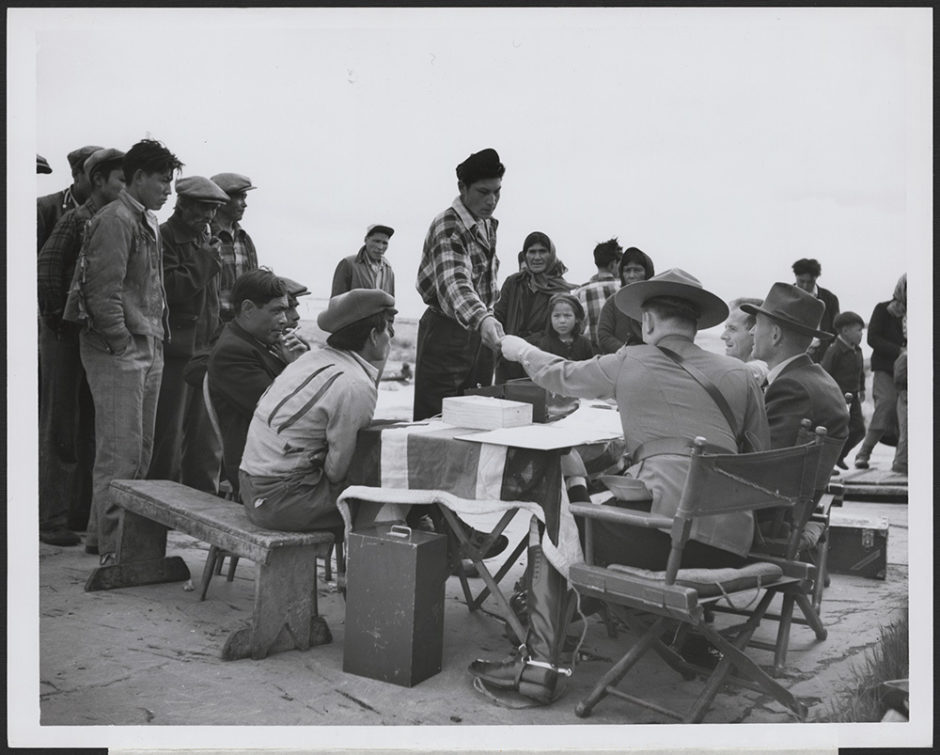

At Wrigley, Tulita, Fort Good Hope, Tsiigehtchic, and Fort McPherson, the story repeats itself. The party arrives to discover many people away and fishing. They appoint a chief, who is immediately skeptical of the offer. Conroy promises that nothing will change, and the testimony of Breynat certifies that these are no lies.

“The people believed everything the bishop said,” Gabriel Kakfwi told Fumoleau, “because bishops and priests are not supposed to lie.”

After the signing, though sometimes before, food and money were distributed. But Conroy and Breynat frequently reiterated that these exchanges did not constitute a purchase of Indigenous land.

“The land was never talked about in the treaties,” Francois Paulette, a Denesuline elder and former chief who would later lead a historic court challenge of the written text of Treaty 8 and 11, told the CBC.

“We talked about … building a relationship with the Crown, that they would not interfere with our mode of life.”

DOCUMENTS LOST

Most Dene people at that time could not read the text of the treaty, but they were not unsavvy. In several places, chiefs requested specifically that Conroy’s promises be written, with copies of the agreement kept in the community.

This was the case at Fort Rae, where Chief Monfwi demanded that the boundaries of Tłı̨chǫ territory actually be drawn on a map, within which they would be free to live as they had before, without interference.

But in many cases, these documents were trusted to local priests, who lost or destroyed them during waves of epidemics. In Fort Rae, there was even the suggestion from Monfwi’s descendants that priests stole the documents at his funeral.

When Conroy issued his final report on the treaty signing, he made no mention of the promises he had made in addition to the text of the treaty. Neither, initially, did Breynat. And when Conroy died in 1922, his promises died with him.

The treaty was ratified by the Canadian government on March 29, 1923. By September, the government had violated its promises by establishing game preserves and penalizing Indigenous hunters for “encroaching” on white settlements outside those areas.

Meanwhile, the territory’s economy was changing, too, to the benefit of white settlers. According to Fumoleau, by 1939, the trapping activity that had sustained northern Indigenous communities for generations had been surpassed by revenue from mining.

“Significantly, not one Indian was yet employed in mining or prospecting at that date,” Fumoleau writes.

A TREATY CONTESTED

For decades after it was signed, most of those subject to Treaty 11 had no idea what the text contained.

When the government’s version of the treaty was first translated and read to an assembly of Dene chiefs in 1969, it immediately caused outrage.

“It was shocking,” said Norman Yakeleya, today the Dene National Chief. “They [had] agreed to … a peace and friendship treaty” — but what they heard was something else entirely.

The government’s text of the treaty contains clauses that both cede Indigenous title to the land and empower settler governments to regulate hunting, trapping and fishing.

At the reading in 1969, chiefs who had been present for the signing, like Wrigley’s Julian Yendo, were still alive.

“They knew that they had not agreed to give up the land,” Lamothe’s paper for the Dene Nation reads.

“They decided to organize themselves and to force the government to accept that the written version of Treaty 11, as drafted by the government, contained fraudulent clauses which had to be corrected.”

That organizing produced the Indian Brotherhood of the Northwest Territories, later known as the Dene Nation.

In 1973, as Canada was trying to force the construction of a pipeline through Treaty 11 territory, 16 chiefs from the N.W.T. went to court in a case known as the Paulette Caveat, asserting that no title had ever been ceded to that land.

“Justice [William] Morrow traveled through the communities, taking testimony of elders that witnessed the treaties — what was said? What was not said?” said Paulette, the former chief for whom the case is named.

“His judgment said that the Dene had a prior interest to over 450,000 square miles [1.1 million square kilometres] of land… that we never extinguished,” Paulette said.

“It is almost unbelievable that the government party could have ever returned from their efforts with any impression but that they had given assurance in perpetuity to the Indians in the territories that their traditional use of the lands was not affected,” Morrow wrote.

While the case was eventually tossed on a technicality, those findings gave legal weight to the testimony of elders, and kickstarted a modern treaty process still underway in many parts of the territory.

THE TREATY TODAY

This summer, as Treaty 11 turns 100, many Dene and Gwich’in will not feel like celebrating. Its story is as much one of dispossession and deceit as it is an expression of Indigenous sovereignty.

But for Gwich’in Grand Chief Ken Kyikavichik, Treaty 11 should not be forgotten.

“I often think about the Gwich’in … on July 25th, [the day] before we signed treaty,” he said. “The government had to come to us to ask for permission, recognizing our sovereignty and our traditional land.”

“Treaty 11 was the foundation of our modern day treaty, one that acknowledged that the Gwich’in had a right to occupancy and use of the land, [that] we had inherent rights.”

Paulette agreed.

“To this day, I stand by those treaties and I will not move from there,” he said.

For Paulette, the oral version of the treaty shows how his ancestors “masterfully … negotiated” terms protecting their use of land and guaranteeing education, health care, and support for elders.

“You should just put that written text aside — that's come and gone, it's finished, we contested that in the courts,” he said.

“But we should honour and respect [our] forefathers and our ancestors that stepped up to keep their sovereignty.”

“It’s still intact today.”

Further Reading:

- Read the government’s text of Treaty 11 in full

- Rene Fumoleau, As Long As This Land Shall Last: A History of Treaty 8 and Treaty 11, 1870-1939

- Rene M.J. Lamothe, "It was only a treaty" : Treaty 11 according to the Dene of the Mackenzie Valley

- Kenneth Coates and William Morrison, “Treaty Research Report: Treaty 11”