August 16, 2021

This is the first of a four-part series examining how one company came to dominate rental housing in Canada's North. Read Part Two here, Part Three here and Part Four here.

Editor's Note: One of the reporters involved in the creation of this series lived in Northview-owned housing.

It was one of Canada's biggest real estate deals, and most of the country barely noticed.

In November 2020, the completion of a deal selling Northview Apartment Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT), the North's largest landlord, to two Toronto real estate investment companies for $4.9 billion was announced. The agreement included about 27,000 residential units and 1.2 million commercial square feet.

If you don't live in the North, or a handful of smaller, largely resource-dependent communities across Canada, you may have never heard of Northview.

But for residents of Yellowknife and Iqaluit, where Northview controls roughly 80 per cent of the multi-unit private rental housing stock, the company is hard to avoid.

In 2019, Northview controlled 26,723 rental units, including 2,654 in the North. It also owned 746,000 square feet of commercial space in the North, part of 1,157,000 square feet it owned across the country. In October 2020, the company counted 1,726 private rental apartments in Yellowknife.

"People have to rent from them because there's literally nothing else here, and they own so much," Amy Badgley, a tenant in Northview's Bison Estates in Yellowknife, told CBC News.

Posts in Yellowknife community Facebook groups asking about tenants' experiences with Northview elicited dozens of warnings and complaints.

But renters have few other options when it comes to rental housing in the North. Decades of policy-makers ignoring mergers and acquisitions that gave one company an ever-greater hold on the property market have left tenants increasingly dependent on Northview for market housing.

"We were aware that there were few options for people in terms of housing," said Wendy Bisaro, a Yellowknife MLA from 2007 to 2015, during which time Northview doubled the number of units it managed in the territory. "But it wasn't something that we talked about in terms of, as a government, what are we going to do?

"I was not seeing that they were going to take over 80 per cent of the market," she said. "I guess I was naive in that regard."

Northern beginnings: Ninety North Construction

Northview began life in 1986 as Ninety North Construction and Development, a partnership of Jim Britton, a former N.W.T. deputy minister, and Kenn Harper, a former teacher and entrepreneur. (Harper declined interviews for this piece, and Britton could not be reached for comment.)

At that time, and in the decade or two that followed, much of the infrastructure that makes up today's North was still being built — mostly on the government's dime.

"We were basically tendering construction projects that could be [anything] from warehouses to schools to health centres," said Bo Rasmussen, who worked with the company from 1994 until its sale last year.

These multimillion-dollar government construction projects fuelled contracting companies, such as Ninety North, which could be trusted to navigate the challenges of building in a harsh environment.

"A lot of the projects that we were doing, if not all of them, were all done on sealift or barge," Rasmussen said. "You basically had to order your foundation all the way to your finishing nails that would go on that one ship … and then you would have to race against the weather … in order to get your structure up."

For companies like Ninety North, these complex logistics were second nature — and communities could transform into a kind of company town practically overnight.

Rasmussen oversaw one three-year span of building in Gjoa Haven, Nunavut, during which the company built the health centre, the RCMP station and a new addition to the school. It also came to own several houses and the local hotel, which it used to house construction workers.

In those early days, Rasmussen said, contracts from the N.W.T. government made up the majority of the company's work. But early on, the company's founders recognized the potential of the rental housing market in the North.

"We could see that there was … not a lot of rental supply," Rasmussen said. "And we … had some great success just for the sake that there were not enough housing units there at the time."

Rapid growth: Urbco Inc.

In 1997, the year Ninety North broke ground on its second condominium project in Yellowknife, the company generated just $2.7 million in rental income. Five years later, it collected nearly 10 times that amount and managed more than 350 units in Iqaluit alone.

Those years also saw the northern contractor's transformation into a publicly traded corporation through a partnership with Calgary-based Urbco Inc.

The company's new-found access to capital fuelled a "buying spree," as the Globe and Mail put it in 2003, "from smaller developers throughout the North."

Ninety North, the construction division, continued to be awarded lucrative government contracts, such as the construction of Inuvik's new hospital in 2002. But the company's reporting showed an increasing focus on extracting value from existing northern rental housing through retrofitting.

Gordon Van Tighem, the mayor of Yellowknife from 2000 to 2012, remembers how, at the beginning of his time in office, "one of the real benefits … was that you did have local families that were investing locally and building up our buildings and setting down roots."

"But then as time has gone on, their families grew up … in most cases, moved away and sold out," he said. "[Northview] were interested purchasers, and it all moved into one pot."

Financialization: Northview Apartment REIT

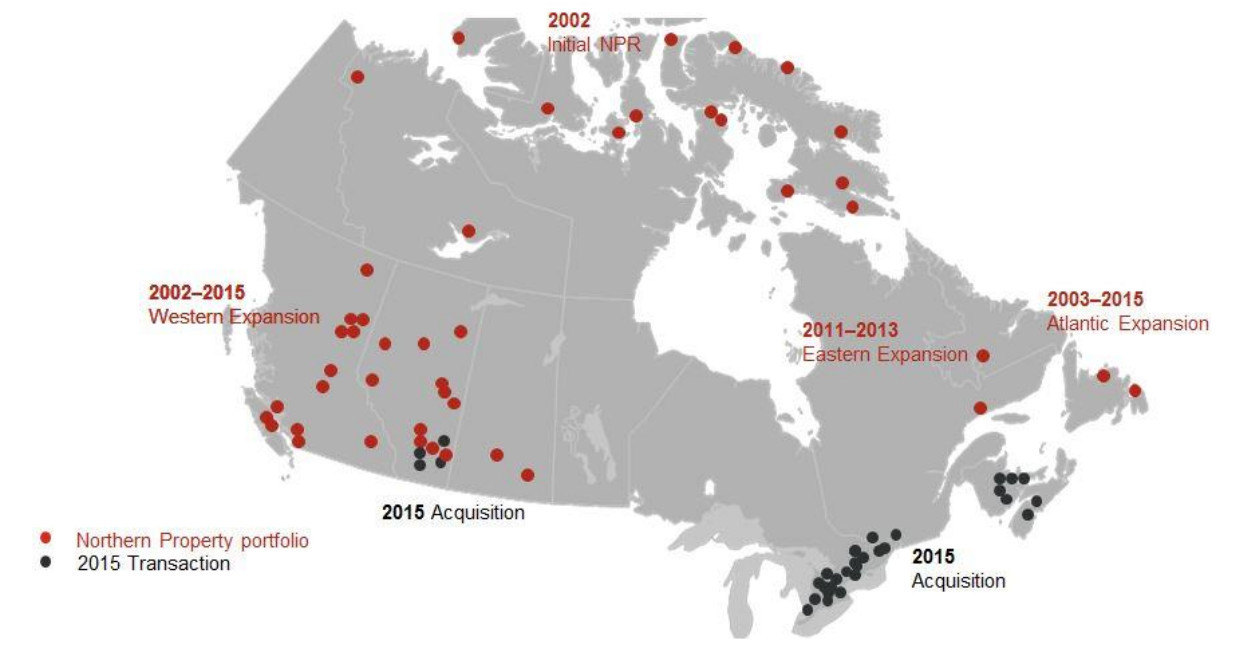

Urbco's rapid growth was supercharged by the conversion of the company to a real estate investment trust, called Northern Property REIT, in 2002.

REITs allow investors to buy shares in a diverse portfolio of rental real estate in exchange for a guaranteed piece of rental income each quarter. That income is then taxed at a much lower rate than corporate profits.

Since Canadian governments began actively encouraging the growth of REITs in the early 2000s following their success in the United States, the investment trusts have come to control huge swaths of rental housing across the country.

Because REITs are required to pay out nearly all of their rental income as dividends, to deliver on the promise of high returns to shareholders, experts say REITs are particularly incentivized to keep costs low and rents high.

In a response to CBC News, Northview contested this idea.

"Those suggesting that neglecting properties or actively allowing them to fall into a state of disrepair is strategic to a REIT do not understand the industry, our business or the expectations of Northview's investors," it wrote.

But the new corporate structure did allow investment from further afield.

"Suddenly, you have investors, really from anywhere, that can start to make money, in new ways, off of housing in the North," said Martine August, an assistant professor and REIT researcher at the University of Waterloo in Waterloo, Ont.

"This shifts the way that businesses are operated … [to] really prioritizing profit-making above all else."

Northern Property REIT used its new-found access to investment capital to fund even more consolidations, expanding in Iqaluit, the capital of newly created Nunavut, and taking advantage of bidding incentives put in place for locally based companies, according to Rasmussen.

Between 2002 and 2008, the company more than quadrupled the number of units it managed and tripled its commercial holdings. Revenue went from roughly $40 million to more than $127 million in five years.

But the company was rapidly spreading beyond its northern roots. While it added nearly 600 units in the territories between 2002 and 2008 — and $57 million worth of downtown Yellowknife commercial property, including the territory's courthouse — it added nearly 10 times as many units outside the North, expanding into similarly resource-dependent communities such as Fort McMurray, Alta., and Fort St. John, B.C.

Weathering the crash

That strategy backfired after the 2008 global financial crisis, which saw resource prices plummet and vacancies at the company's properties skyrocket.

In January 2009, "it became clear that the collapse in oil prices would have an important impact on the economies in Western Canada," Northern Property REIT's annual report from that year reads.

At the company's new acquisitions in Alberta and British Columbia, vacancies multiplied. Even its northern properties, which had previously boasted near 100 per cent occupancy, saw vacancy rates increase to as much as seven per cent.

The crash challenged the company's strategy of rapidly acquiring residential properties in low-vacancy resource boom towns — and revealed just how a lack of options for renters had allowed the company to skimp on maintenance over time.

In its 2009 annual report, Northern Property acknowledged that "during the boom years, it had been very difficult to keep buildings in the condition that Northern Property and its tenants expect."

The company hired a "small army of workers" to carry out "deferred maintenance tasks, which had been impossible to do" when apartments were being turned over to new tenants "back-to-back," it said.

But in what is partly an illustration of the appeal of REITs for investors, Northern Property weathered the 2008 crash fairly easily, relying on the long-term, government-backed leases for office space and public housing that made up the bulk of its northern portfolio.

By 2011, the company was back in fine form, boasting near 100 per cent occupancy and expanding to new remote communities in Labrador and northern Quebec.

Role of northern politics

Northern politicians from this time didn't acknowledge the growing monopoly that Northern Property held in their communities — or even their governments' increasing reliance on the company.

But the company inserted itself into northern politics in a big way in 2014, when it suggested it would stop renting to N.W.T. residents on income assistance, citing $250,000 in late rent payments.

"When we ran the numbers … we just can't keep losing that money," Lizaine Wheeler, vice-president of residential operations, said at the time.

In 2013, the company's rental income had for the first time surpassed $175 million. Net rental income after expenses was more than $100 million.

But the company still demanded that the government guarantee all rent payments for those on income assistance before renting to those tenants.

In 2014, Northview suggested it would no longer rent to people on income assistance. The company denies ever having implemented the policy.

The announcement eventually elicited a response — five months later — from the N.W.T. Human Rights Commission, which warned against discriminating on the basis of "social condition" but issued no binding decisions.

Politicians, too, took notice. In 2014, Bob Bromley, then the N.W.T. MLA for Weledeh, called out the territorial government for relying on the company for public housing.

"I have heard of [Northern Property] tenants without running water for months at a time being refused transfers to new apartments," he said in the legislature.

"Apartments are sitting empty here while people in treatment programs are being evicted."

A spokesperson for Northview told CBC News it never had a policy to deny housing to those on income assistance.

More money, more problems: Northview Apartment REIT

But the growth of Northern Property was only beginning. In 2015, the company acquired the residential holdings of True North Apartment REIT for more than $535 million and became Northview Apartment REIT.

The acquisition saw Northview go from managing just under 11,000 residential units to more than 24,000, including dozens of buildings in Ontario, Quebec and Western Canada.

"This REIT, at the time, became the third-biggest … multi-family investment trust in Canada," said the University of Waterloo's Martine August.

In the years that followed, the North accounted for an ever-diminishing part of the company's portfolio.

But in the same period, northerners became more vocal about worsening conditions at the company's buildings.

In 2015, a mother of two living in Northview's Fort Gary building in Yellowknife complained of a rampant beetle infestation. The public housing authority, which secured her the apartment, called it a "nuisance" and said it posed no harm.

The same year, at the company's Hudson House in Yellowknife, where apartments were leased for $1,300 a month, residents went public about a cockroach infestation that had gone unresolved for three years.

When cleaning crews arrived, they left a tenant's apartment unlocked, resulting in the theft of the family's jewelry, television and religious books. The company billed the tenant $1,400 for pest control.

Two years later, another tenant went public about 80 complaint calls they made in a 10-month period about feces and vomit in the common areas of Yellowknife's Norseman Manor — also owned by Northview. The company offered to relocate the tenant.

Northview said it would not comment on previously published media stories.

In 2017, a tenant at Yellowknife's Norseman Manor went public about 80 complaint calls they made in a 10-month period. Northview said it does not comment on previously published media stories.

Decisions by an officer of the N.W.T.'s Rental Office from this time record repeated instances of the company overcharging fees, unlawfully withholding security deposits and leaving units to deteriorate from mould, water damage and infestations.

In some cases, the Rental Office issued decisions penalizing the company. At Hudson House, for example, one tenant was awarded just over $3,000 in rent reductions following the cockroach infestation, after painstakingly documenting Northview's efforts to eradicate it.

But even where there were building-wide issues, the rental officer could only compensate individual tenants who filed complaints and had documentation to prove a lack of maintenance.

While one tenant at Yellowknife's Lanky Court was compensated more than $4,000 after maintenance crews left mouldy, stinking holes in common areas when repairing a leaking water pipe, the Rental Office records no compensation for other tenants of the same building.

Meanwhile, the Rental Office was helping Northview recoup millions of dollars in unpaid rent. By 2018, its net income had surged past $150 million a year.

In a response to CBC News, a spokesperson for Northview said they would not comment on individual tenant stories or Rental Office decisions.

They did, however, note that the company has invested "more than $58 million" in its northern properties since 2015, "and continues to invest at per suite rates significantly higher than … rental peers in the south."

Swallowed whole: Northview Canadian High Yield Residential Fund

If the 2010s saw Northview's connection to the North erode through its aggressive southern expansion, the end of the decade completed the company's transition into an international rental behemoth.

In the fall of 2019, Northview was approached by Starlight Investments, a Toronto real estate investment company with more than $20 billion in assets, about an acquisition.

While other companies had made offers, none could beat Starlight's price of $2.5 billion — $700 million over Northview's most-recent valuation.

Ultimately, Northview was purchased by Starlight and KingSett Capital, also based in Toronto, for $4.9 billion.

The deal saw the transformation of Northview again, from a REIT to a high-yield residential fund. It retained its northern properties, lost much of the rest and became an even smaller part of a larger company's vast portfolio.

"It kind of took it back to … where we were when we were kind of starting out," said Rasmussen, who left the company with the acquisition last fall.

Yellowknife North MLA Rylund Johnson sees it differently. Northview's northern holdings, he said, are now "a small, tiny fraction" of Starlight's multinational empire. He questions whether northerners' rent money is funding southern expansion instead of investments in the local community.

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. data shows fewer than two dozen new rental units have been built in the North in the past five years.

"You haven't really seen Northview take an interest in building new units [in Yellowknife] either. So they're not even doing what they originally did, which was add a lot of housing stock."

Tenants, too, are beginning to organize against the company. Following a devastating fire in a Dartmouth, N.S., apartment owned by Northview, tenants filed a class-action lawsuit against the company, alleging it failed to respond to complaints of a careless smoker who started the fire and died. In July, the Nova Scotia Supreme Court allowed the case to proceed.

Northview says it remains committed to addressing "the critical housing shortages faced by the communities in which we operate."

"Since [1986], and without interruption, the company has provided rental accommodation for thousands of northerners in communities across the territories," a spokesperson wrote in an email.

For Northview's investors, the outlook, if anything, has improved.

- Read part 2 of the series here: Living with Northview in Yellowknife

According to the company's prospectus for the 2020 sale, two-thirds of its rental income now comes from long-term government leases, making it a safer bet than ever for investors. Building in the North has only become more expensive. And with apartments "at near full occupancy in markets from coast to coast, rent growth has … accelerated," it says.

Investors are told to expect 10 cents on the dollar, every year.

CORRECTION | A previous version of this story mistakenly said that in October 2020, Northview counted 1,726 private rental apartments in Yellowknife. In fact, the company counted 1,051 private rental apartments in Yellowknife in September 2020.