September 30, 2021

WARNING: This story contains distressing details that may trigger people who have lived through similar experiences.

Until recently, day school students were excluded from initiatives to repair generations of damage imposed on Indigenous communities by the federal government under the authority of the Indian Act.

That’s changing, says a woman who attended the Lennox Island Day School and is now supporting hundreds of other Mi'kmaq on Prince Edward Island as they prepare compensation claims. As part of a class-action settlement reached with the federal government in 2019, former day school students are eligible for between $10,000 and $200,000, with settlements based on the amount of abuse suffered.

“The only [difference] between residential school and day school is that you got to go home at night,” Tiffany Sark, a student at the Lennox Island school in the 1970s, told CBC News in a recent interview.

“The reports that we get from the day school, generally, without involving names, are a wide range of harms and abuses,” said Sark.

“No amount of money can change the fact that the abuses happened and that they had long-term effects on people.”

With the discovery of what appears to be unmarked graves at former residential school sites across Canada this year, it’s become harder for non-Indigenous Canadians to deny or downplay the horrors that occurred within the walls of those institutions over the generations.

The church-run, government-funded boarding schools operated in Canada for more than 100 years, with the stated goal of forcing Indigenous children to learn English, embrace Christianity and adopt the customs of the country's white majority. As part of the Indian Act, parents were forced to allow their children to be taken to the schools.

Islanders may have mourned the discoveries in other provinces without realizing that Prince Edward Island has its own stories of abuse and lost culture at educational facilities under federal regulation.

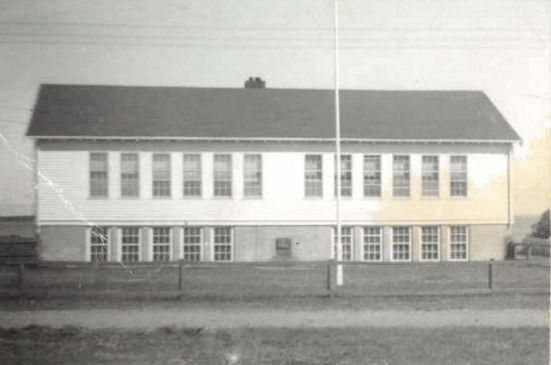

Two so-called Indian day schools operated in this province.

One was in Rocky Point, but for only a few years between 1915 and 1922. On Lennox Island, an Indian day school was in operation for 118 years, between 1869 and 1987.

Many survivors of this latter school remain today, and still carry trauma from their time as young students not allowed to speak their own language and in some cases abused by non-Indigenous teachers.

Support for claimants

Sark said she suffered both emotionally and physically during her time at the Lennox Island school. These days, she works to support both residential and day school survivors, as Health Resolution and Cultural Support Coordinator for the Mi’kmaq Confederacy of P.E.I.

Lately, she’s been extra busy helping more than 200 day school survivors as they apply for compensation under the class-action settlement before the deadline next July. Legal help is available free of charge as part of the process, but Sark offers emotional support to individuals preparing claims — whether that’s helping with the writing or arranging access to a computer to do the work.

“It's going good. It's hard work though,” says Sark, who said the hardest part of the process is that survivors have to relive, in vivid detail, the abuse and mistreatment from decades ago.

“I just look forward to the claims being completed and having some peace.”

As part of the day school settlement process, a $200 million legacy fund has been established for health and healing initiatives. Last month, a national organization — called the McLean Day School Settlement Corp. — was launched to support day school survivors. It will be in charge of the legacy fund to support day school survivors.

Sark is keen for more details on how those funds will be distributed, given how many people on Lennox Island continue to cope with fallout from the day school. She said, for some, that’s in addition to intergenerational trauma caused by time spent at residential school in Nova Scotia and families torn apart by the so-called Sixties Scoop.

“What's it going to be in the long term?” she wondered during an interview with CBC News. “What kind of programs, what kind of funding is going to be available in the long term, you know, for mental health, for education, for addiction?”

Apologies matter

Then there’s the question of an apology.

Day school students were not just excluded from the $1.9-billion Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement in 2006. They were also left out of former prime minister Stephen Harper’s formal apology to residential school survivors in 2008.

“In my personal opinion, it would be good to have an apology from the federal government,” said Sark.

Officials with Indigenous Services Canada say there are currently no plans to formally apologize to day school survivors, though a statement to CBC News acknowledged that the mistreatment of Indigenous children is a “tragic and shameful part of Canada’s history.”

“Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada understands that an apology can be important to class members in their healing and ability to move forward. We will continue to work with survivors, Indigenous partners and all Canadians to advance reconciliation, promote Indigenous languages and culture, and support the healing and commemoration for all those affected by Federal Indian Day Schools.”

The statement goes on to say that “the legacy of trauma inflicted by Indian Residential Schools has caused and continues to cause profound pain and will never be forgotten,” and the Federal Indian Day Schools settlement “represents a historic milestone in Crown-Indigenous relations efforts to address harms associated with attendance at federally run Indian Day Schools.”

For the former Lennox Island students, it is indeed a milestone. But they have waited a long time for this acknowledgement, and want meaningful reconciliation efforts.

“This was always swept under the rug,” said Patsy Gavin, who recently took to social media with a series of posts sharing her story of sexual and physical abuse at the school, at the hands of both staff and fellow students who themselves had been assaulted.

“A lot have said that I shouldn't have brought it up, but more people have come to me to say that I did the right thing,” said Gavin.

“Within five minutes, I had four women saying, ‘We want to go there, we need to deal with this.’”

Today Gavin spends much of her time looking after members of her community, and helping them find healthy ways to process and cope with their trauma.

She said there’s some concern in the community that the day school settlement money could cause problems for those already struggling with mental health and addictions tied to what they experienced. She, too, struggled with addiction but says she’s been sober for 23 years now.

Gavin has already submitted her claim under the Federal Indian Day Schools settlement. She said it’s still under investigation, by someone who will read the details of her trauma and decide how much money that is worth. But Gavin said it’s not about the payout; it’s about the good she hopes to do with that settlement money.

“Two hundred thousand is not what I'm worth; I'm worth a hell of a lot more than that,” said Gavin.

“And what I'm planning on doing with my money, if/when I get it, is to start a healing foundation to help everybody else, because it took us 200 to 300 years to get this way. I don't want it to take two or three hundred years to get back to a healthier lifestyle.”

Preparing the claims

In the meantime, work continues on assisting former day school students with their compensation claims. The law firm assigned to handle the settlement is Gowling WLG, but other lawyers are helping as well.

One of them is Charlottetown-based Pamela Large-Moran, who also served as an adjudicator in the residential schools class-action settlement.

She agrees that “day school students suffered a lot of the same abuses and experiences, unfortunately, that residential school survivors did.”

Timelines around the day school settlement process are tight, she told CBC News. The settlement was in 2019, and the compensation process opened in January of 2020 — but it wasn’t until July of that year that an order was obtained from the federal court to let independent lawyers help class-action members.

Former students have until July of 2022 to complete the claims process — a massive undertaking considering the numbers involved.

“There are 140,000 former day school students from across the country,” said Large-Moran. “There were 40,000 residential school survivors, and that was a five-year open claims period. So this is fairly short compared to that.”

She said estate claims are also part of this process, meaning relatives of former students who died after July of 2007 can also apply for compensation.

Large-Moran said she can appreciate how difficult it is for survivors, and their families, to relive decades-old trauma as they work on their claim, but she hopes it can also help them heal.

For some, it’s the first time they’ve ever opened up about what happened to them.

Large-Moran recently worked with a woman who told her about a “very serious” incident of abuse she suffered as a six-year-old at the day school.

“She was approximately 70 years old, and she had never told anyone about that experience in her life. And she said: ‘You know, I buried it.’ And we know the impacts that can have, when you suffer childhood trauma like that.”

In some cases, she said, it’s easier for survivors to share their stories with someone they don’t know, who will respect their confidentiality.

In others, there’s comfort in having someone you know, who has been through something similar, walk you through the claims process.

What matters most is that day school survivors feel supported during this process, the lawyer said.

“I really consider it an honour and a privilege, you know, that people share their stories with me and trust me,” said Large-Moran.

Support is available for anyone affected by their experience at residential or day schools, and those who are triggered by news reports such as this.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former students and those affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419.

In this CBC series

WEDNESDAY | Hidden history: Survivor stories from the Indian Day School on Lennox Island

THURSDAY | Days of reckoning: What's happening now with the settlement and the push for an apology

FRIDAY | Next steps: What Mi'kmaq on Prince Edward Island want and need now to help them heal