November 11, 2018

It was nearly 8 p.m. and dead quiet on a typically hot and muggy evening near the coastal community of Batangas City in the Philippines.

Until the hum and rattle of an approaching motorcycle broke the silence.

It was June of this past summer, and Luzie Gammon was in the kitchen of the dream home she built with her Canadian husband, Barry Gammon, when the hum was replaced by the piercing and unmistakable sound of a gun being fired, over and over and over again.

She ran to the front porch to see her husband, 66, struggling to close their gate on an intruder. "We're pushing together, and he just keeps shooting and shooting," she said during a recent interview with The Fifth Estate.

And then, she said, "my husband drops." Gammon paused as she struggled to recall the details. And then she continued.

"His face, his blood on the floor and … he's bleeding. At that moment, it's just like, this is not real, what's going on? I'm acting and doing, but it's not registering in my mind. Is this real?"

She snapped suddenly back to reality when she realized their seven-year-old son, JJ, was standing behind her, frozen.

"I grabbed my son and pushed him … inside the house," she continued.

"'Stay here, and I'll get some help,'" she recalled telling JJ. "But he didn't want … it's just really … heartbreaking. He told me, 'We need to help daddy.'"

She told him to stay put.

"'No, Mommy. I'm going to come with you,'" he said. "We will die all together."

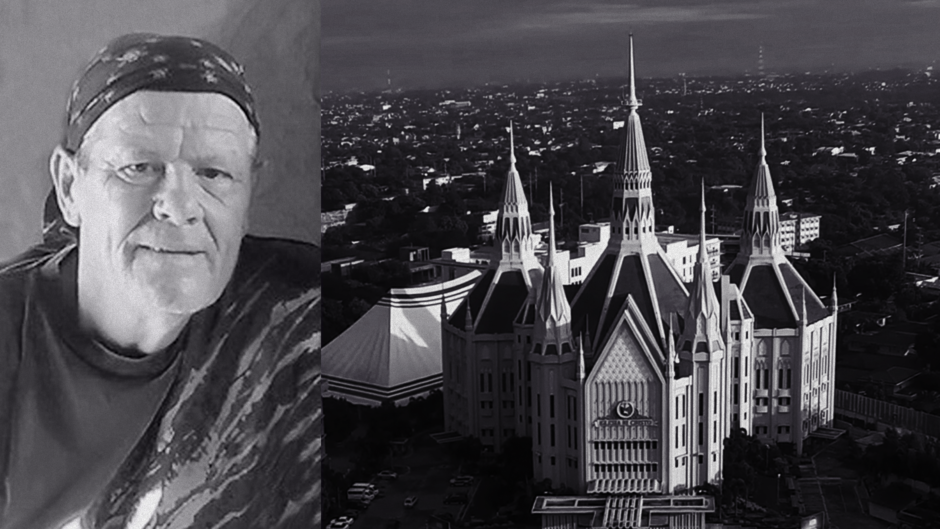

Barry Gammon died on that June 24 evening in the Philippines. Luzie and JJ survived. Five weeks after the fatal shooting, they left the Philippines for Canada.

As she tearfully recalled the events of that night to The Fifth Estate, JJ approached and put his head on her chest. They hugged.

"He's really strong, really strong for me," she said.

They are safe in Vancouver now. But their lives were forever shattered, a Fifth Estate investigation shows, likely because of something as benign as a property dispute with their neighbours. Yet at the time, they had no idea how aggressive and dangerous those neighbours could be.

Their neighbours were members of a powerful and wealthy church, one that has millions of followers around the world, including in Canada, known as the Iglesia Ni Cristo.

II.

The INC, as it's known, is headquartered in a grand castle-like temple in Metro Manila. Its tall, pale green spires pierce the skyline of the Philippines' most populated city.

Iglesia Ni Cristo (or Church of Christ in English) is more than 100 years old. It has almost 7,000 congregations around the world, including more than 80 in Canada, from small towns like Durham, Ont., and Abbotsford, B.C., to at least one in almost every major Canadian centre.

Thousands of Canadians attend those churches, worshipping and taking part in charitable causes.

In 2009, the INC was taken over by the founder's grandson, Eduardo Manalo, who is referred to as the INC's executive minister.

The Fifth Estate investigation reveals a church that changed under Manalo's leadership.

The Fifth Estate reviewed hundreds of pages of court documents, police reports and media articles and spoke to dozens of former members of the church as well as police sources, legal and financial experts and local journalists. The investigation shows a pattern, with church members in the Philippines becoming increasingly aggressive, dangerous, corrupt and willing to kidnap and even kill anybody who stands in their way.

The investigation also raises the question: Do Canadians who attend or support the INC really know their church and what could happen when people choose to speak out?

INC members in Regina dismissed criticism against the church in 2016, in a video posted online by the church.

"Whenever people are saying bad things or trying to bad talk our church administration … it's definitely the work of the enemy," one member said.

"Since the beginning, God made my faith strong," said another. "So, I don't even lend an ear to those people [who criticize the church]."

In a letter from lawyers acting for the church, it denied the findings of The Fifth Estate investigation and refused to provide specific information, saying it needed more details.

However, the INC recently came under the microscope of Canada's Immigration and Refugee Board.

Three former church members fled the Philippines for Canada, claiming their lives were in danger from the church.

In three separate decisions in 2017 and 2018, the board accepted the testimony of all three former members and granted them refugee status.

According to one decision, the life of the claimant would be at risk from a church that has "the means and motivation to seriously harm or kill."

In another decision, the board determined the police in the Philippines are willing to protect the INC, even suggesting a variety of ways church critics could be killed.

"There are various scenarios where [the claimant] could be assassinated," wrote the board in a decision from March of last year, "from staged police encounters to death in custody to contract murder in a country where hitmen are plentiful and cheap."

The decisions go on to say the church commands a lot of power in the Philippines, in part because its members vote as a block, giving it influence over who gets elected.

Its leader, Manalo, was recently appointed a special envoy for overseas concerns by Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte and can be seen in news reports shaking hands with the president.

The INC is a "cult-like" church, the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada wrote, citing a third claimant who said the INC "cannot be touched by the Philippines government, judiciary or law enforcement or even by the president himself."

III.

Lowell Menorca heaves boxes piled high with day-old cakes and bread from the loading dock of a high-end grocery store into his paint-chipped white minivan. He slams the rear hatch shut and manoeuvres onto the busy streets of Burnaby, B.C.

Menorca escaped to Canada more than two years ago from the Philippines and pleaded his case before Canada's refugee board. He now fills his days delivering donated food to shelters and refugee centres around B.C.'s Lower Mainland.

His father was a senior member of the church leadership. Menorca himself grew up in the church compound in Metro Manila and went on to become a minister.

But when Manalo took over, Menorca said he noticed a sharp change.

"We've seen how the executive minister, his family and even the church council ministers have elevated themselves into an exorbitant lifestyle," he said.

"When you start going around as a minister, with luxury vehicles … and having [access to an] Airbus, just to go from one place to another."

It's a problem because that lifestyle is being funded by church members' donations, Menorca said.

Then, in 2015, someone started anonymously leaking church financial secrets in a popular online blog. It exposed allegations of questionable spending and later revealed documents showing the church was deeply in debt.

Menorca said the church desperately wanted to know who was behind the leaks, and INC ministers suspected of releasing confidential information started to go missing at that time. And then church members came for him.

"They frisked me, handcuffed me and put a jacket over my head, dragged me out of the compound," Menorca said.

In July 2015, as many as 10 police officers protecting the church took him away at gunpoint, he said.

At the time, he was a minister based at a church in a rural area of the Philippines, southeast of Manila.

"They dragged me into this big ambulance, but when we got inside the ambulance, it was actually empty. And all you see is a desk, it's a table, with surveillance cameras. And then there was a chair. I was handcuffed to the chair, and then we sped off."

Menorca said the leaks had hit the church where it hurt it the most. He believes donations were on the decline.

"They had to do something, and they were willing to kill for it."

After 17 hours of interrogation, often at gunpoint, Menorca insisted he had nothing to offer. Then, he said, church interrogators decided they were done with him.

They handcuffed him inside a small, dilapidated car parked in the countryside, and then, he said, tossed something in the backseat and ran.

"I was able to get a glimpse of it, and when [his kidnappers] ran off, I immediately knew that it's a grenade," Menorca said.

"When I saw it, [I thought], 'That's it.' That's the end of me. The only thing I could do was bow my head and pray for my wife and child. That's it. But then I realized when I was able to finish my prayer up to, 'Amen,' that's pretty long for a grenade."

The grenade didn't go off, and Menorca lived to tell the tale.

Eventually, he and his family escaped to a neighbouring country, where they are in hiding. In 2017, Menorca went on to obtain refugee status in Canada. Ever since, he has been working to expose problems with the church.

Lawyers for the INC deny Menorca's story and say he's criticizing the church as part of his quest for permanent residence status in Canada. The church also points to a series of criminal libel lawsuits launched against him by members of the church while he still lived in the Philippines. They say he can't be trusted to tell the truth.

The lawsuits claim Menorca is defaming members of the church in the Philippines with his story.

Despite the lawsuits, the IRB granted refugee status to Menorca in 2017, another former member in 2017 and Menorca's mother this past summer. They all live in Canada now.

Others were not so lucky, like the Montreal-born man living in the Philippines, Barry Gammon.

IV.

As far as new neighbours go, when the INC began constructing a church next to Gammon's home in the hills southwest of Manila two years ago, he and his wife, Luzie, thought: How bad can it be?

Then they met the church members and their construction crews.

"They just are, like, arrogant," said Luzie. "There's some arrogance in them that they just do everything they want. They don't care that they're bothering us."

The problems began from Day 1, she said, with construction noise late into the night. Vehicles came and went at all hours, headlights shining in their windows and waking them up. Construction vehicles left their road rutted and damaged.

Once the church was built, problems continued with vehicles and people arriving early in the morning and leaving late at night for church services.

Then one day, in December 2016, a group of church members parked in front of their gate blocking their driveway. Barry Gammon had had enough.

"You're on my f--king property," he can be heard saying in a video of the encounter captured on his cellphone.

The church member he confronted, it turned out, was a local lawyer.

"He knows the law and [that] my husband is just a foreigner and that he doesn't belong to [the] Philippines," said Luzie. "That's exactly his words, and he's going to deport him ... he's got a lot of connections to the immigration."

"You're an asshole, too," the lawyer can be heard saying. "We're not done. I will see you in court."

Shortly after that, in 2016, the lawyer launched an immigration complaint with the Philippines Bureau of Immigration in an attempt to have Gammon deported.

"I was in my own home minding my own business and not looking for trouble," Barry Gammon wrote in a letter of defence to the Bureau of Immigration. "This church group has a lot of pull, and no one wants to stand up against them.

"[The lawyer] stated I was a stupid American and was not wanted in the Philippines."

Three months later, the case was dismissed for "lack of merit."

"You’re safe now. You are with mommy and some friends. You are here in Canada."

But the confrontations didn't stop there. They continued on for months, involving other members of the church. And finally, another heated exchange over late-night noise.

"That last time was really the worst," said Luzie Gammon. "They were really, really mad that time. They said: 'We're not done.'"

Two days later, two men arrived on a motorcycle and shot Barry Gammon to death.

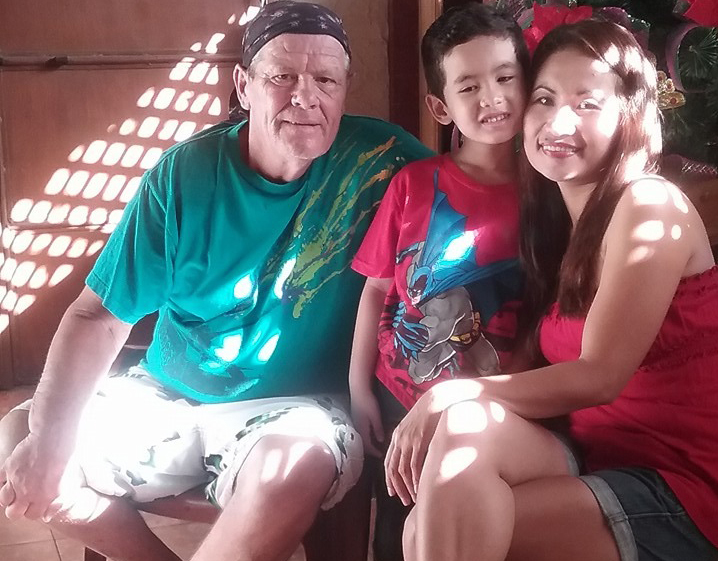

That was in June of this year. By August, Luzie and her son, JJ, landed in Vancouver. They rolled bags stacked high on carts through the international arrival doors at the airport looking tired, overwhelmed and sad. Lowell Menorca was there to meet them.

He is assisting Luzie Gammon find her feet in Vancouver, helping provide temporary accommodation and emotional support.

"You're safe now," Menorca said, leaning down to hug JJ at the airport. "You are with mommy and some friends. You are here in Canada."

Luzie Gammon and her son, JJ, arrive in Canada.

V.

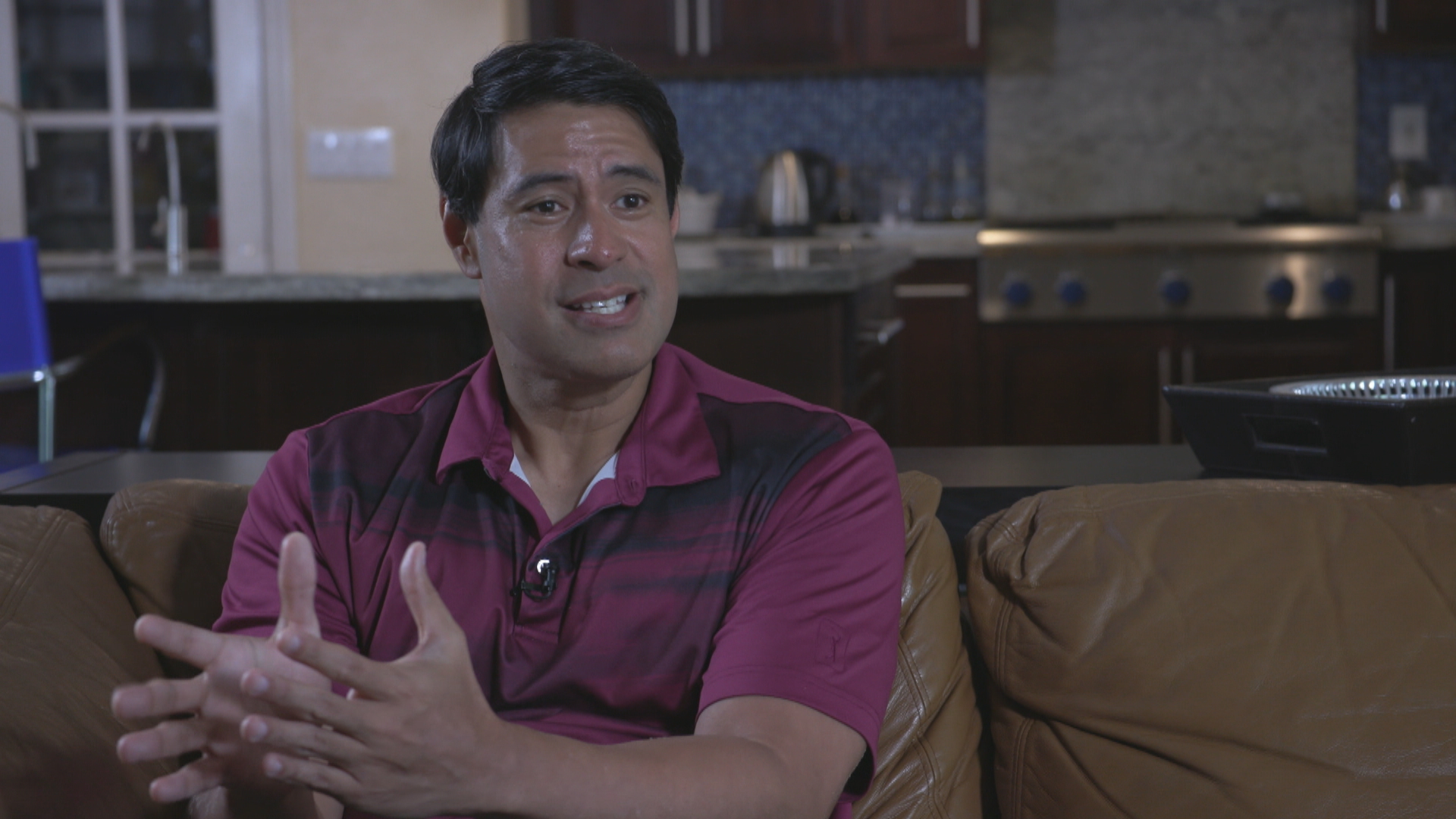

It's August 2018, and after months of investigating the INC, a Fifth Estate team is heading to northern California, following a tip. A senior church insider appears willing to be interviewed. Before he left the church, he led one of the largest INC congregations outside the Philippines.

He has agreed, through an intermediary, to meet at a friend's home, a modest suburban house in a sprawling California neighbourhood. He wants the location of his family kept a secret.

He is reluctant and fearful, but in the end, Rolando Dizon agrees to be interviewed.

"Love has been replaced by fear," he said, referring to the church.

Tall, well-spoken and charismatic, Dizon makes an immediate impression. And once he starts, he doesn't hold back.

"We have to be completely submissive without asking any questions," he said. "Completely submissive to all the mandates of [INC leader] Brother Eduardo V. Manalo because to do otherwise would be to jeopardize your own salvation."

Shortly after Manalo became the INC'’s leader a decade ago, as a prominent U.S. minister, Dizon had a front row seat to the changes he says Manalo brought to the church.

"When it comes to Eduardo and his entourage, it's all first class," he said.

"Not just the Airbus, but the lifestyle. The houses, the mansions, the swimming pools, multiple places where he resides at.… The things that they're able to purchase on a whim, it's staggering. Where does that come from? There's only one source, that's the offering from the brethren."

And then Dizon says he noticed strange things happening to the money that had been donated by his church members when Manalo came to California.

"They would segregate some of the cash, a good amount of the cash, and they would bundle that together and there are collectors who show up on a particular day to pick up the bag of money, the bag of cash, and they transfer that all the way to the U.S. main office," he said.

"I've seen it with my own eyes. Exactly what they do with the cash, we have no idea. We cannot ask about that."

Congregations in the United States and Canada generate a lot donations for the church, Dizon said, for the simple reason that people living in the West often have more money to give. Dizon calls this region the INC's "cash cow."

He said his congregation, one of hundreds in the U.S., could bring in as much as $1 million a year.

But there are laws about moving cash across international borders. For example, if you are travelling with more than than $10,000 in cash, you must declare it. And there are strict rules in Canada and the United States about moving charitable donations out of the country.

"You can kind of connect the dots when you consider the fact that congregations are preparing cash during [Manalo's] arrival," said Dizon, who believes Manalo or other senior ministers could be using visits to the U.S. to illegally bring cash back to the Philippines.

In a letter, INC lawyers say separating donated cash from cheques is "not an unusual financial practice." The Fifth Estate also found no evidence the INC moved any donations illegally across international borders but did learn Homeland Security in the United States has conducted several interviews with expelled church members, asking questions about the movement of cash in the U.S. and Canada.

In an email, Homeland Security wrote that it "does not confirm or deny ongoing investigations," but The Fifth Estate independently confirmed a senior INC church member was caught at the airport in Seattle lying about the amount of cash he was carrying.

Matt Pareja, a member of the church's senior council, was detained in 2015, allegedly attempting to smuggle cash out of the United States. Three years later, the status of his case is unclear.

Dizon said he knows and has seen a lot. He's worried he or his family will pay a price for his decision to speak out.

"They're willing to kill for [the leader of the church]," he said. "And they can take that kind of mentality, that kind of approach, the aggressive approach outside the Philippines, which is why I am very, very concerned about my life and the life of my family."

VI.

Autopsy photos and police reports depicting violence linked to INC members in the Philippines, obtained by The Fifth Estate, paint a gruesome picture. Multiple gunshots to the head and body of one man, another shot through the eyes and a car riddled with bullet holes.

According to media reports, police reports and interviews by The Fifth Estate, Jose Fruto is one of three expelled INC members killed in the Philippines. Two were killed in 2017. A third went missing the same year and is believed dead.

Fruto was particularly outspoken against the church, even offering a letter of support in Menorca's Canadian refugee board hearing.

"Every fanatic member of the church is willing to die for the church. Therefore, they are also willing to lie and kill for the church," he wrote in November 2016.

"Please approve [Menorca's] petition for asylum in your country. His returning here to the Philippines is a death wish."

Seven months later, a gunman sprayed Fruto's car with bullets as he slowed down at an intersection south of Manila. He died instantly.

In all three killings, The Fifth Estate found no evidence that INC leadership had anything to do with them.

But time and again, those who went against church members found themselves targeted, including Gammon.

The CBC has obtained a report from the Philippine National Police in Gammon's case and it, too, points a finger at members of the INC.

Entitled "Progress Report" and dated June 26, 2018, it said Gammon and his wife had numerous "altercations with certain members of the nearby chapel (INC)."

The report goes on to say because there is "a longstanding spat between the couple and several churchgoers … there is a very good likelihood [that] any of those whom the victim may have displeased greatly [could] have [had] the victim shot to death."

VII.

The autumn sun barely peeks over the Toronto skyline, and already, hundreds of Canadian INC members are lined up outside a large white stucco building nestled among suburban homes in the west part of the city. The trademark INC-style spires stand guard on either side of the main structure.

It's Sept. 22 and the leader of the INC himself, Eduardo Manalo, is scheduled to be in Toronto on a trip from the Philippines. He's crisscrossing North America in celebration of the church's 50-year presence in the West.

Within minutes of arriving, The Fifth Estate team is identified and obviously isn't welcome.

Security guards shine flashlights into the camera lenses. Other members hoist large vinyl signs above their heads to block the view and jostle the Fifth Estate crew.

In the end, there is no opportunity to ask Manalo questions raised by the Fifth Estate investigation. A white SUV believed to be carrying the leader of the INC rushed into a back lane behind the church and was quickly blocked by church security.

"This is a worship service. That's why we don't want you here," said Don Orozco, an INC member.

"Just like what I did in Sacramento," he said. "I will be with you for the rest of the day."

Orozco was in northern California a few weeks earlier when The Fifth Estate was covering another visit by Manalo.

The INC leader was scheduled to speak at the basketball stadium in downtown Sacramento. Thousands of people streamed in for the service.

The moment The Fifth Estate team stepped out of the elevators in a Sacramento hotel, church members followed and filmed the team's movements.

Clearly, the INC had been warned the CBC was in town.

The Fifth Estate attempts to speak with Eduardo Manalo at a church dedication in Toronto.

As The Fifth Estate team drove to the event, two vehicles were right behind. Eventually, we stopped and confronted them. A smiling and energetic Filipino man greeted us. It was Orozco.

"I was just going to make sure that you are all right," he said when confronted by Fifth Estate host Bob McKeown. "I am here to guide you, not to stop you."

Initially, he described himself as a journalist for a U.S.-based Filipino newspaper. Eventually, though, he acknowledged he is also an INC member.

He's asked about allegations the church is moving money illegally across borders to fund the lavish lifestyles of the leadership.

"You know, in terms of skimming money, [this] is something you cannot question when it comes to our offering," he said.

"It is something that is very sacred to us. And I am so embarrassed that you think that the church administration is trying to do something, skimming our offering.

"Unfortunately, the only thing I could say is that all of this is trash."

As for the killing of Canadian Barry Gammon and the accounting of what happened that night by Luzie Gammon, Orozco denied the church had anything to do with the death.

"It's her word against our word," he said. "So, I cannot further comment on that."

In a letter to The Fifth Estate, lawyers acting for the church called all of the allegations "scandalous, outrageous and untrue."

"You've been seeing us in the bad light. Why haven't you seen the better light of the church?"

"I am telling you, you've been focusing on the church as you've been seeing us in the bad light," Orozco said. "Why haven't you seen the better light of the church?"

It's true — the church does humanitarian work around the world. The INC has projects in the Philippines, Brazil, Australia, the U.S., Africa and Canada.

Only a few weeks ago, the INC organized an Aid for Humanity Event in the North End of Winnipeg. According to a media release, it donated more than 3,000 care packages and served hot meals to local residents.

Recently, premiers and mayors across Canada wrote letters to praise the church and congratulate the INC for its anniversary in Canada. Even Prime Minister Justin Trudeau issued a letter.

"For 45 years, the Iglesia Ni Cristo has brought together Canadians who are committed to upholding Christian ideas of faith and service," Trudeau wrote.

"On behalf of the Government of Canada, I offer my best wishes for a memorable celebration."

However, a question remains: Are any of the Canadian politicians who wrote letters of support or Canadian organizations that partner with the INC aware of the allegations of violence and corruption back in the Philippines?

Eventually, The Fifth Estate Team parted ways with Orozco in Sacramento and headed to the event. Two vehicles were close behind.

And then we found the door where we believed Manalo would exit the stadium after his sermon. Finally, a chance to question the man who leads this organization.

As The Fifth Estate team waited, a group of serious-looking men with walkie-talkies and earpieces formed a ring around the door.

Minutes later, a security guard for the facility arrived and said we have to leave or he would call the police. We complied and headed back to our vehicle.

Host Bob Mckeown finds the tires of the van The Fifth Estate team was travelling in slashed.

That's when we were in for one last surprise: three of our tires had been slashed. Knife marks 2.5 centimetres long scarred each of the crushed tires.

Minutes later, INC member Don Orozco appeared in the parking garage.

"I have no idea," he said, shaking his head. "It happens."

VIII.

Back in Vancouver, Luzie Gammon and JJ huddle around an iPad with Menorca. Menorca slides photos of INC security members across the screen, one after another, to see if a face sparks a memory.

Then Gammon asks him to stop.

"I'm 100 per cent sure it's him," she said, pointing at one of the men. "I know it's him. And I can feel in my heart it's him."

"Me, too," said JJ.

"You, too?" Menorca asked, looking at JJ. "Are you sure that's him? You saw him?"

JJ nods his head, and they stare quietly at the photo of the man they believe killed their husband and father.

Since identifying the person they believe is the killer, Gammon has been in touch with Global Affairs Canada. They've instructed her to get in touch with the Vancouver Police.

She's been told Canadian police can potentially involve Interpol in her case. She doesn't trust the local police back in the Philippines.

Gammon wants the shooter behind bars in hopes he will identify whomever ordered him to pull the trigger. She wants the INC held accountable if it can be proven it was involved.

"I want them to get punished for what they did to my husband," she said. "I promised my husband's body that I will do anything to give him justice."

With files from Eric Rankin