June 21, 2020

"It's always good to go outside," says Peter Bird. "It's more bonding time."

Bird is one of five teenage boys stuffed into a big van making its way down a winding road. It's March, and the Grade 9 students are heading towards a snowy forest, their classroom for the day.

Every week they leave their high school in Stanley Mission, Sask., to spend half a day learning outdoors.

The narrow, tree-covered road gives way to a partially cleared area with four buildings — two still under construction — and three tents. The sound of busy people radiates from the tents. Saws and planers are buzzing, shaping blocks of wood into sleds. Smoke rises up from a fire pit, snaking through thick canvas.

You can hear laughter, too — more since Bird and the boys arrived.

The teens have gulped their first breaths of fresh morning air and are ready. They stand at attention.

"You have a few options," says one of the teachers, Isabelle Hardlotte, starting the meeting by laying out their choices for the day: snowshoeing to set up rabbit snares or making bannock in the kitchen.

- Reporter's Notebook: Reflecting on Stanley Mission

- Bullied to death; almost: One Cree woman's story of survival

Hardlotte is the Cree culture language teacher and land-based co-ordinator for the Rhoda Hardlotte Memorial Keethanow High School, which is named after her late mother-in-law. Hardlotte uses humour in her lessons but sometimes is tough on the students. It's a tactic to help them learn.

"At the beginning of the year, they were taught how to set rabbit snares, how to cut down trees, to feed rabbits, to attract them," Hardlotte says. "And it is very important because we do live in the bushes. The kids need these skills."

Beyond providing basic life skills in the north, Hardlotte says the site connects them to the land and their language.

"I was a product of the residential school syndrome, where if I spoke my language, I was beaten for it."

"It is very important for the kids to connect to their culture," Hardlotte said. "The language and the culture are all intertwined. It is very important for the kids to learn their language and to learn their culture ... for a sense of belonging and their self-identity."

WATCH | Learning traditional ways at the land-based site:

Amachewespimawin: Shooting for the Cree way of life

Amachewespimawin First Nation, commonly known as Stanley Mission, is a small northern town and reserve on the edge of the Churchill River.

Stanley Mission is part of the Lac La Ronge Indian Band, one of 49 First Nations across Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba that are part of Treaty 6.

Generations ago, birchbark canoes lined the banks of the Churchill River. They were the transportation method of choice for Indigenous travellers in northern Saskatchewan.

Today, clusters of trucks and cars dot the parking lot in front of a big Co-op store perched near the river’s edge. It sells everything from winter boots to bug spray. Next door there’s a Chester’s Chicken restaurant. Further up the road there’s a grocery store that opened earlier this year.

A trip to the mall is a three-and-a-half-hour drive south to Prince Albert, which has movie theatres, drive-thru restaurants and all the trappings of modern life.

Here in Stanley Mission, there’s not much of that. There's an old church and an abundance of wildlife.

Learning how to live off the land helps the younger generation understand how their ancestors survived — and how they might support themselves in the future.

For many people in Saskatchewan, when they think of Stanley Mission, a very old church comes to mind.

Holy Trinity Anglican Church is known as the oldest church in Saskatchewan, which is true. It was built between 1854 and 1860. It has a heavy timber frame. Its stained glass windows, locks and hinges were imported from England and floated down to the site on the Churchill River (then known as the English River).

What many people may not think of when they see it is the complicated history it represents.

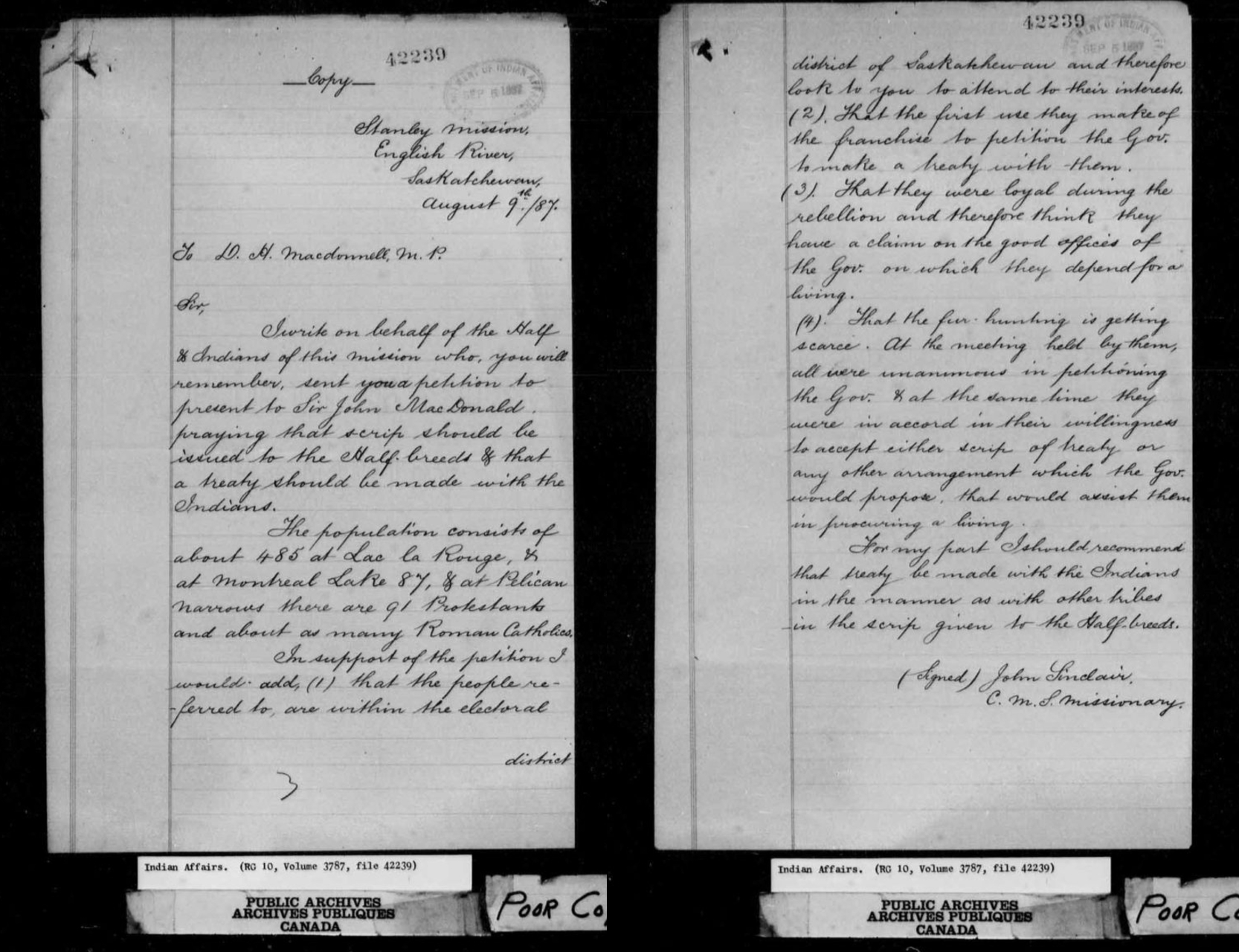

On Aug. 9, 1887, John Sinclair, a missionary in Stanley Mission, sent a letter to the federal government. In it, Sinclair asks the federal government to make a treaty with the First Nations people at Lac La Ronge, Montreal Lake and Pelican Narrows.

He also writes about the scarcity of fur hunting in the area. It gives insight into the situation in this part of Saskatchewan in 1887.

For decades, the church was the heart of the townsite, but in the 1930s, people started moving to the other side of the river after the First Nations reserve was established there.

For a time, the church fell into disrepair and sat empty with broken windows, and it looked like it might be consumed by the elements. It was designated a national historic site in 1970 and a provincial historic site in 1986.

The Amachewespimawin First Nation took over running its schools from the province in 1977. Soon after, teachers started using the outdoors as a classroom.

Members of the school board pushed harder for cultural immersion following tragedy in 2016, when the area was rocked by multiple youth suicides. As a result, the Amachewespimawin First Nation received a one-time $300,000 grant from the Saskatchewan government for a land-based project.

The grant paid to take a specific group of high-needs kids out into the bush each day for a few months, and it had positive results. In the following years, the school applied for further grants, and through the National Indian Brotherhood Trust Fund they received funding to continue and expand the project. The Trust Fund is meant to support education programs aimed at healing, reconciliation and knowledge-building for First Nation communities.

The Trust Fund grant was originally given to the National Indian Brotherhood in a settlement for residential school survivors. In that spirit, the board hired residential school survivors, including Hardlotte.

She said that when she was at school, she was punished for any acknowledgement of her culture. It had a lasting effect on her generation.

"I was a product of the residential school syndrome, where if I spoke my language, I was beaten for it," she said. "A lot of the parents my age did not teach our children the language."

Hardlotte said she and her husband decided not to teach their children Cree because of their own negative experiences. She said they thought it would be best to only teach them English.

"Now, in hindsight … I wish I did not do that. I wish I taught my children my language."

Although Isabelle Hardlotte regrets not teaching her own children Cree, she's remedying this now by teaching classes at the land-based education site that incorporate her mother tongue.

Words like awas (get away) and atim (dog) fly through the air as she teaches the group of boys. A few lace up snowshoes, grab wire and wire cutters and head out to set rabbit snares. Others head to the kitchen — a modest building with a stove, counter, plastic tables and chairs.

"You get to do a lot of stuff out here," Bird says, making bannock. On this particular day, he and another boy are busy plopping chunks of flour, baking powder, sugar, lard and water into a cast iron pan sizzling with boiling oil and fat.

Susan McLeod keeps a watchful eye on the teens. She’s a cheerful, patient woman who works full-time at the land-based site’s kitchen.

"This is our language. This is our culture. And it is not intended to be taught in the classroom."

Once the bannock is cooked (and partly eaten), the snowshoers return with news that there were no rabbits on the school’s nearby trapline. So, the group decides to step outside and practise their axe-throwing, with Hardlotte keeping a close eye.

None of the axes stick to the target, but that’s not really the point.

Bird's throw chops a small section of bark off the tree but the blade doesn’t stick. Teachers and teens are cheering and jeering to encourage him. For Bird, this is about being together.

He says it’s important to learn in this way because it makes stressful things he faces outside of school seem more manageable.

"It helps a lot of other stuff in life," he says.

Education was among the 94 calls to action put forward by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2015, including new legislation that would provide funding to “develop culturally appropriate curricula.”

It’s something Hardlotte supports.

"This is our language. This is our culture. And it is not intended to be taught in the classroom," Hardlotte says. "Everything that I learned I learned out in the bush, from my grandparents and from my mom and my dad."

Hardlotte says even rambunctious students in the classroom come out and are respectful at the site and eager to learn.

"Someday, hopefully, these kids are going to grow up. They're going to have their own children. So now they have some knowledge that they can pass to their children so that a lot of knowledge is not lost and the culture is not lost."

Sallie McLeod, the director of education for the Amachewespimawin First Nation, says she isn't concerned about the students missing out on hours in the classroom.

McLeod knows that math, science and English are important for academics in the future, but between Grades 4 to 9, other skills need to be taught, too.

"We need to take our cultural language and take it back on the land. And that's how our land-base was born," McLeod says. "Retaining your culture and language is more important than the other core subjects."

McLeod believes that helping kids learn about why they live where they do, and how they can do it well, helps with their mental health.

"There's so much to enjoy. The nature and the language and the culture is all interconnected and we need to get back [to it] — if not for peace, at least for internal healing."

Beyond culture and language, Hardlotte says she hopes students learn how to be self-sufficient. After all, they’ll be adults before too long.

She says the land-based approach allows students to fail and then try again, with the support of teachers.

"If you can plant a seed in these kids, to learn to be independent, to learn to do things on their own, then even if you've only planted one seed, then you have accomplished something," she says.

Hardlotte and the land-based education team hope to build lodging at the site for overnight stays and larger trips that could qualify for educational credits.

"This is important, because I live in Stanley Mission and this is how I have to learn the wild," says Kiersten McLeod. The Grade 4 student is a smiley, curious girl who has a passion for learning.

The next day, McLeod is among a group of chattering Grade 4 students, clamouring down a path through the woods. Everyone is excited. Something special is happening today.

The class is being taught how to properly treat a wolf carcass. The wolf was donated after a local hunter shot it, as was a section of moose meat.

The kids are given a choice: watch the wolf-skinning demonstration or learn how to cut up and prepare moose meat.

The Grade 4s wince, giggle and stare at the wolf bones as the skin is carefully peeled off. Some remark at the terrible smell as the tendons are exposed.

In the kitchen, a smaller group quickly grabs knives and begins slicing the moose meat into tiny sections to be fried. The small group gets to use large hunting knives under the watchful eye of the teachers.

After the moose meat has been cooked and eaten, the kids head to the tents where two elders are hard at work making sleds from scratch and rattles from fish skin.

Elder Isaiah Roberts slowly planes down wood in his shop. He's been crafting handmade sleds for children. Elder Peter Roberts has been using burbot fish skin to make rattles with fish bones inside.

Hardlotte says it's important to have the elders teach these skills.

"One of the things that I explain to kids: go observe, go learn. It's a skill that's going to be lost," Hardlotte says. "And if you observe, some day you might try it, and you might be the only person that will have that skill. And it'll be your responsibility to pass on."

It's something Noreen McKenzie is very aware of. She’s a shy student who is passionate about things she cares about. She said land-based education is fun, and that it feels good to be outside in nature.

"That's how I want to grow up," she said. "And I want to teach my kids [about it], too."

By the time the students need to head back to town, the smell of freshly cooked moose meat clings to their clothing. The teachers smile and crack jokes as they prepare for a lunch break before the next batch. The Grade 4s wave as they reluctantly walk back to the bus.

Hardlotte stands and looks at the site with pride. She lights up when she talks about the program and its students.

When looking at mental health issues and the high rate of suicides for Indigenous youth, Hardlotte says they don't know yet if the program will help. But they’re betting on it.

"This is just the beginning of the program that we're starting and we've only been here since January," she says. "Give it a few years, when it's in full swing, and then we'll see what it brings."

The place is peaceful, even when the students are present. Hardlotte says sometimes she and the students will stop so they can hear their own heartbeats.

"It is so quiet. It's beautiful," Hardlotte says. "They really enjoy being out here."