Seeing Dad through his lens

Digitizing our home videos helped me understand my dad 16 years later

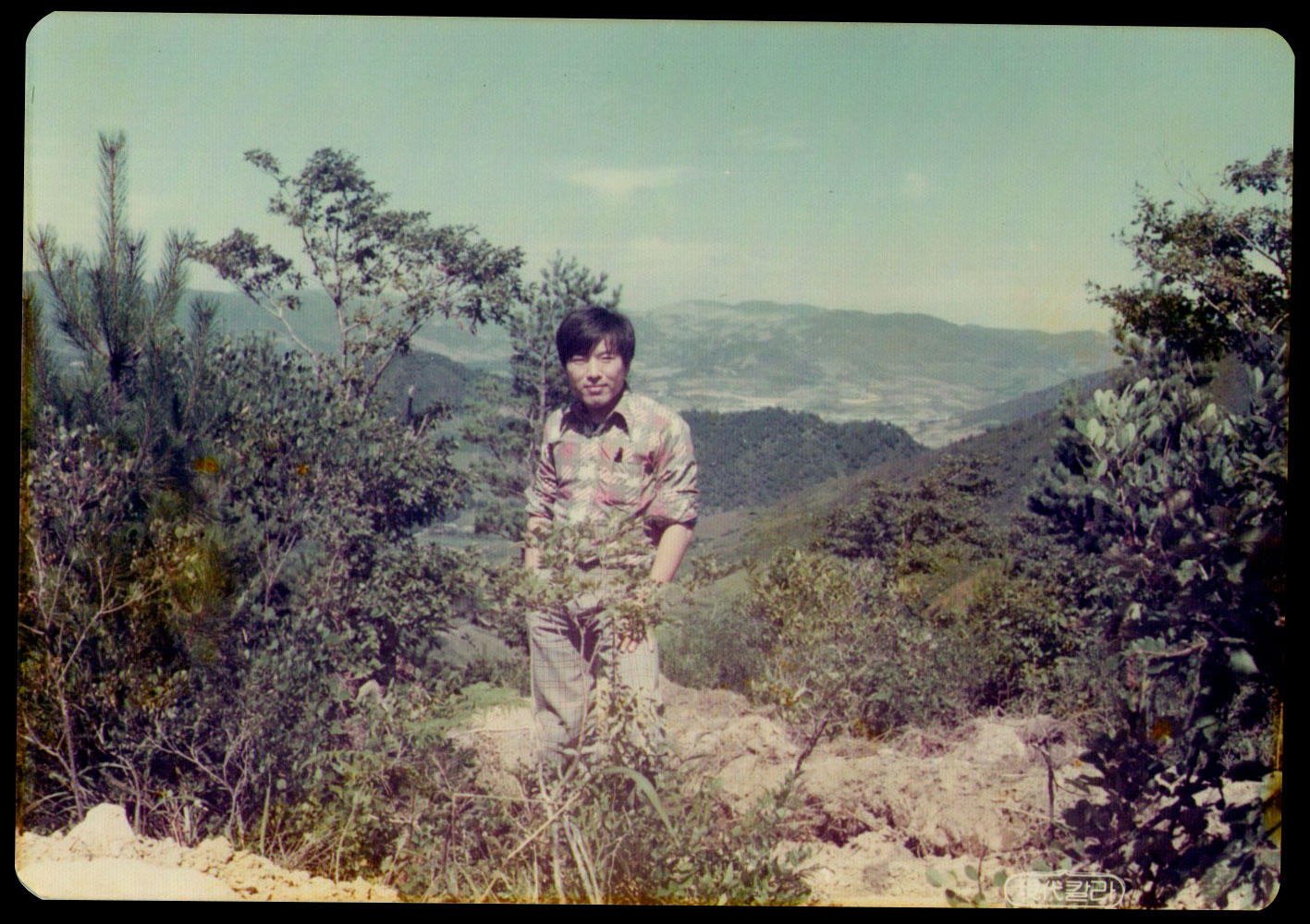

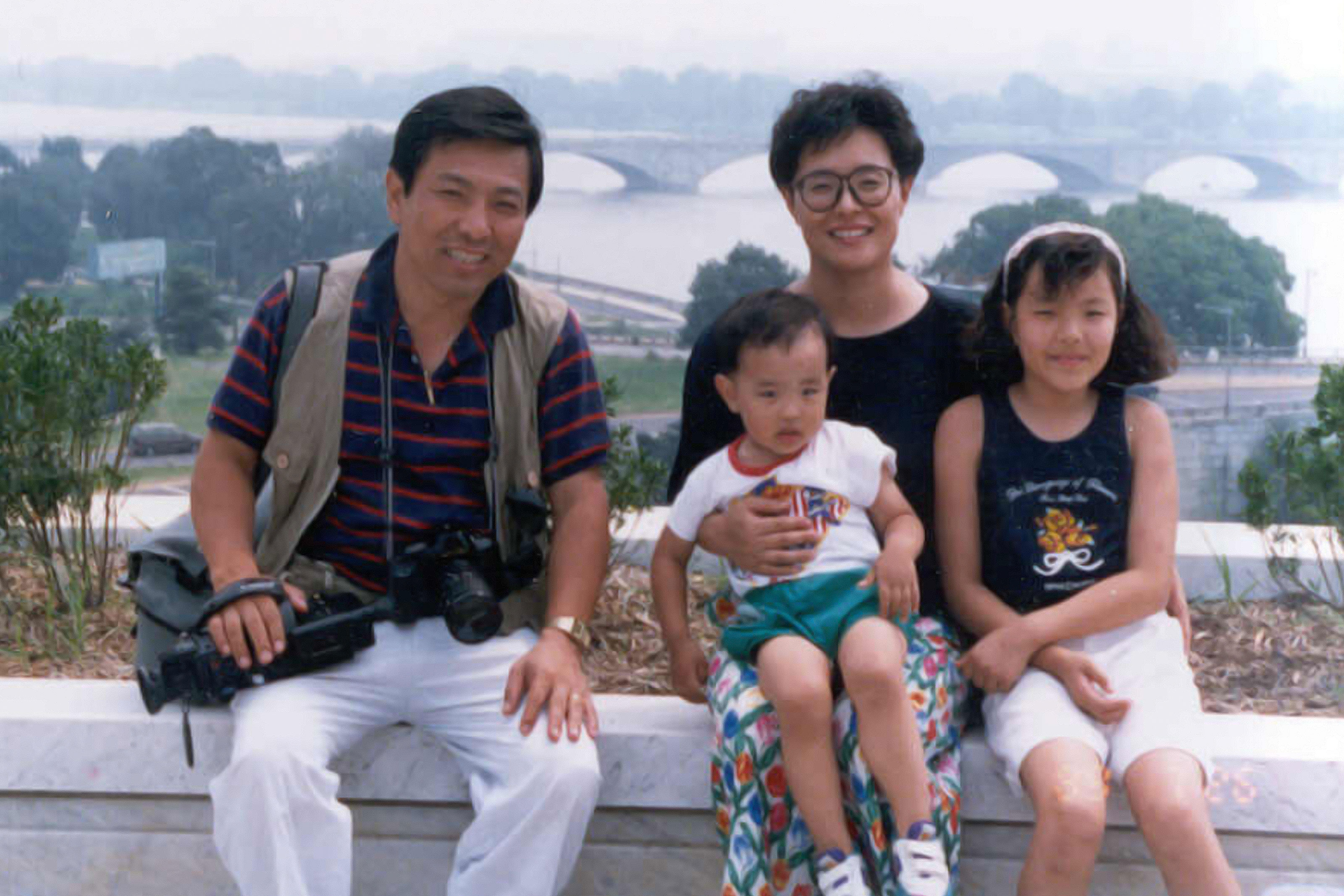

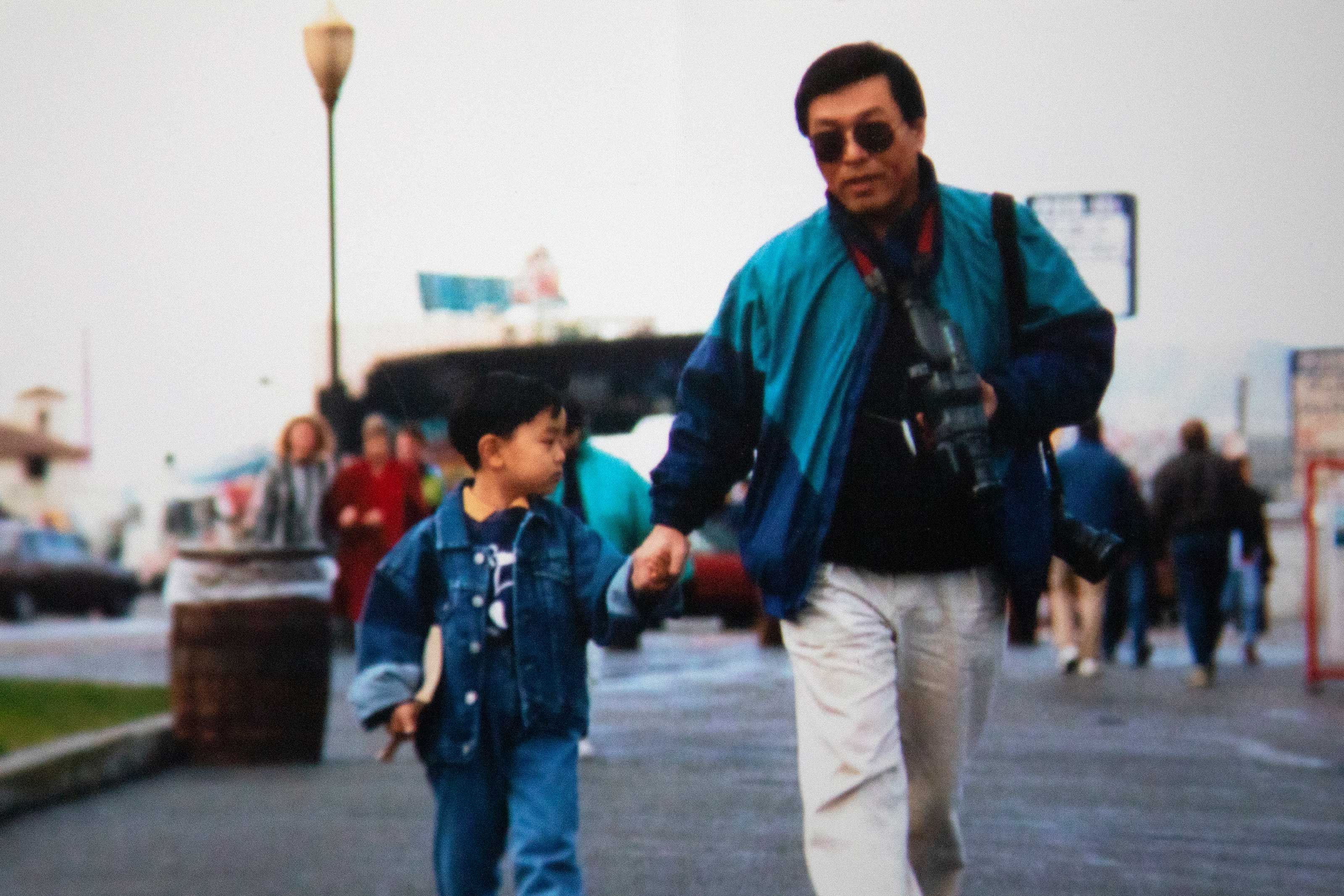

My dad, Kwahn Wook Kim, was our family documentarian. He was always *that* dad with the camera or camcorder pointed at us, recording our family gatherings, trips and school events.

Like many photographers, he was rarely in front of the camera. When pancreatic cancer took my dad’s life in 2005, I vividly remember my mom and my sister struggling to find any decent images him to display at his funeral.

For almost 15 years, the boxes filled with his prints and tapes, all neatly labelled with his handwriting, sat in closets collecting dust.

I was never curious — and perhaps not ready — to see what was inside. Mourning is an odd and unpredictable process like that. Then, a friend told me about a documentary he had made using his family’s home videos. He offered to lend me his equipment to digitize our own tapes, so I finally decided to dive in.

Back in South Korea, my dad was an architect. His claim to fame was being the chief architect of Yongpyong Ski Resort, the first such facility built in South Korea, that later hosted the giant slalom and slalom events during the 2018 Olympic Winter Games.

My dad carried his camcorders to film his business trips, when he visited and studied resorts around North America and Asia.

Most of this footage is, frankly, boring.

For hours, he recorded his observations while walking from building to building. He barely speaks in these videos, but I can hear him breathing or concentrating on holding the camera steady.

He stops and holds the camera on mundane details I don’t understand, but probably mean something to architects: the layout of lockers, the corner of a hotel room, the wayfinding signs.

But when he enters a room with a mirror, I’m instantly interested. I see his reflection and it’s the first time I’ve seen a moving image of him since he died. It’s a brief moment. He pans the camera away, finding something else that interests him.

I scanned hours and hours of tapes for these scenes, trying to catch a new detail each time.

After moving to Canada in 1993, my dad and I grew apart. Our story is not uncommon. Adjusting to life in a new country was a challenge for all of us and I was like many immigrant children: I rejected anything that made me stand out, including my parents.

One of the biggest culture shocks I had was seeing how openly affectionate my friends’ parents were with their children. The words “I love you” were not something that came easily to my dad, so I convinced myself he didn’t love us. He had such high expectations. He never seemed happy. I never felt like I was good enough for him.

I avoided talking to him about the important stuff. Instead, we fought, we argued, we disagreed. We never figured out how to communicate, and I resented him for many years.

When I started to digitize our home videos, I yearned to find moments I hoped would prove my memories wrong. Had I built up my dad to be some kind of villain?

Initially, I was left disappointed: it’s hard to find moments of intimacy when the person you want to see is holding the camera the whole time.

I found one scene with us together. In it, the camera is focused on my face. My dad’s hands are on my cheeks, pulling my skin back. I repeat the word 아빠 (dad), the sound of the word changing as he caresses his hands around my face to make different expressions. We’re both giggling. Now I’m repeating the word 자동차 (car).

I had no recollection of this memory — or any others that felt similarly — and it was strange watching my dad and me sharing this small, fun moment. The clip ends, and I was left knowing I’ll never remember what his hands felt like on my face.

In another scene, I feel my dad’s love in an unexpected way. It’s a tape labelled “Whistler business trip,” taken in 1992, the year before our family immigrated to Canada. The video is again from Dad’s point of view as he films from the passenger seat of a car, talking with a friend who helped our family with the immigration process.

My dad films as his friend explains Metro Vancouver’s geography. They discuss housing prices. My dad asks about schools in the area.

I realize he is researching by filming, just like on his business trips, for our eventual life as Canadians.

I’ll never get to ask my dad what he intended by filming hours and hours of these videos: that will be just one of hundreds of conversations with him I have in my own head for the rest of my life. But 15 years after his death, I got to experience my dad’s own unique love language: planning our future so my sister and I never grew up wanting; documenting our family, for hours and hours, so he would leave a legacy of memories.

My dad never told me he loved me as much as, or in the way, I wanted. But the tapes showed me, in the only way my dad could, that he absolutely did.

Since becoming a photographer, I’ve wondered if my dad would have approved of my career choice; growing up, I always felt he envisioned the traditional definitions of success (doctor/lawyer/business school) for me. I often think of him when I pick up my camera and hope he’s proud of me. I hope that we would have connected through our shared passion.

This First Person article is the experience of Taehoon Kim, a Vancouver photographer and visual creative producer. For more information about CBC's First Person stories, please see the

FAQ.