SAVING

CHINATOWN

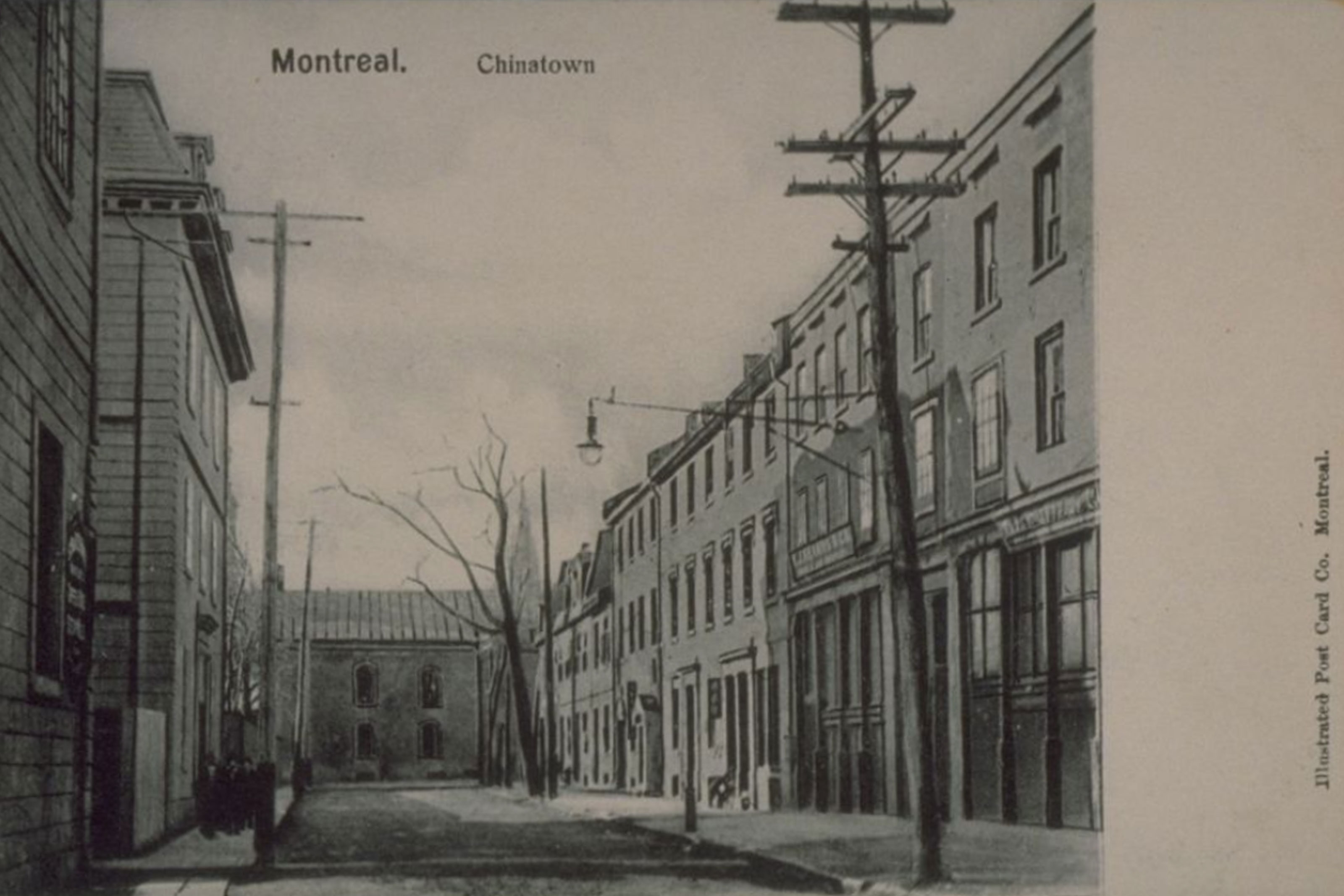

A stone’s throw from Montreal’s famed Old Port neighbourhood, another landmark area of the city is struggling for survival.

Bound by its four paifang gates, Chinatown has been a cultural hub for the city’s Chinese community for more than a century.

But the neighbourhood has been losing its footprint in Montreal for decades, and many fear that without urgent intervention, the encroaching city could soon swallow the historic community.

Community members warn Chinatown is at a precarious tipping point. Developers have bought up chunks of land and buildings, amassing significant swaths of property many fear could be destined for highrise condominiums.

Walter Tom

Member of Montreal’s Chinatown Working Group

“There’s a real chance that this Chinatown could [be] extinct soon,” said Walter Tom, a member of the community-driven Chinatown Working Group, which is fighting to preserve the neighbourhood.

Tom immigrated to Canada in the 1960s and grew up in Quebec City, where the small Chinatown that once served as a community gathering point in that city slowly dissolved and the community dispersed.

Montreal’s Chinatown was a safe haven — a place where you would hear Cantonese in the streets and find familiarity and family tucked into the greater francophone metropolis.

He remembers being enchanted by the sights and sounds, and feeling welcome in a neighbourhood brimming with acknowledgment of his identity.

“Chinatown, for the many Chinese communities, is really our home — our sanctuary,” he said.

“This is where we can seek relief from xenophobia and other racism.… This is where we grew up. This is really chez nous.”

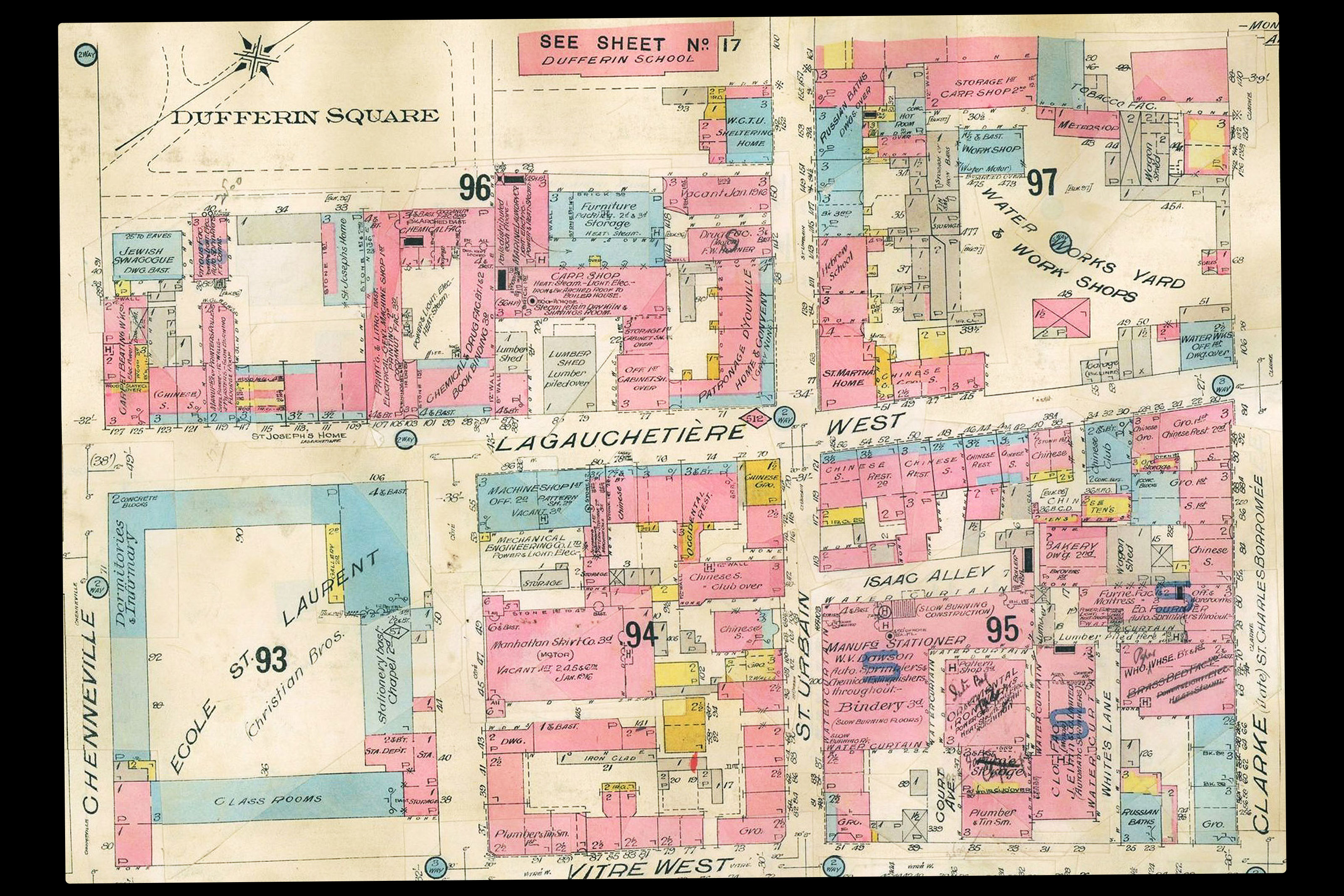

The neighbourhood’s origins are a road map to the early demographics of the city; the Jewish, French Canadian, Scottish and Irish communities all had shops, homes and places of worship in the bustling area.

At the turn of the century, immigrants from China set up small businesses of their own, primarily laundries and restaurants, to cater to the crowds catching the train at the nearby station. At one point, Montreal had the second highest Chinese population in Canada.

As new immigrants arrived, Chinatown served as a gateway, helping many find work and pieces of home and community as they learned French and English and adapted to life in Canada.

But as the decades marched on, discriminatory immigration policies limited the incoming population.

Families were separated and those who remained in Montreal worked to send money home to China while building new communities in Chinatown. The neighbourhood compressed, but those who remained held tight to their community and a dense sliver of the city steeped in the traditions and legacy of its ancestors.

It’s a legacy runs deeper than the import souvenir shops and bubble tea restaurants that have become associated with the narrow, bustling De la Gauchetière Street.

Tucked inside some of the neighbourhood’s historical buildings are art studios and bookstores, tearooms and cultural associations, temples and traditional medicine practitioners.

Some of the people who inhabit the small apartments above the bustle mark touchpoints in their lives by the landmarks that disappeared — the long-vanished pagoda, the grocery stores and restaurants that fell to time and the memories of a Chinatown that once was.

Amelia Wong-Mersereau

Neighbourhood advocate and former Chinatown Working Group member

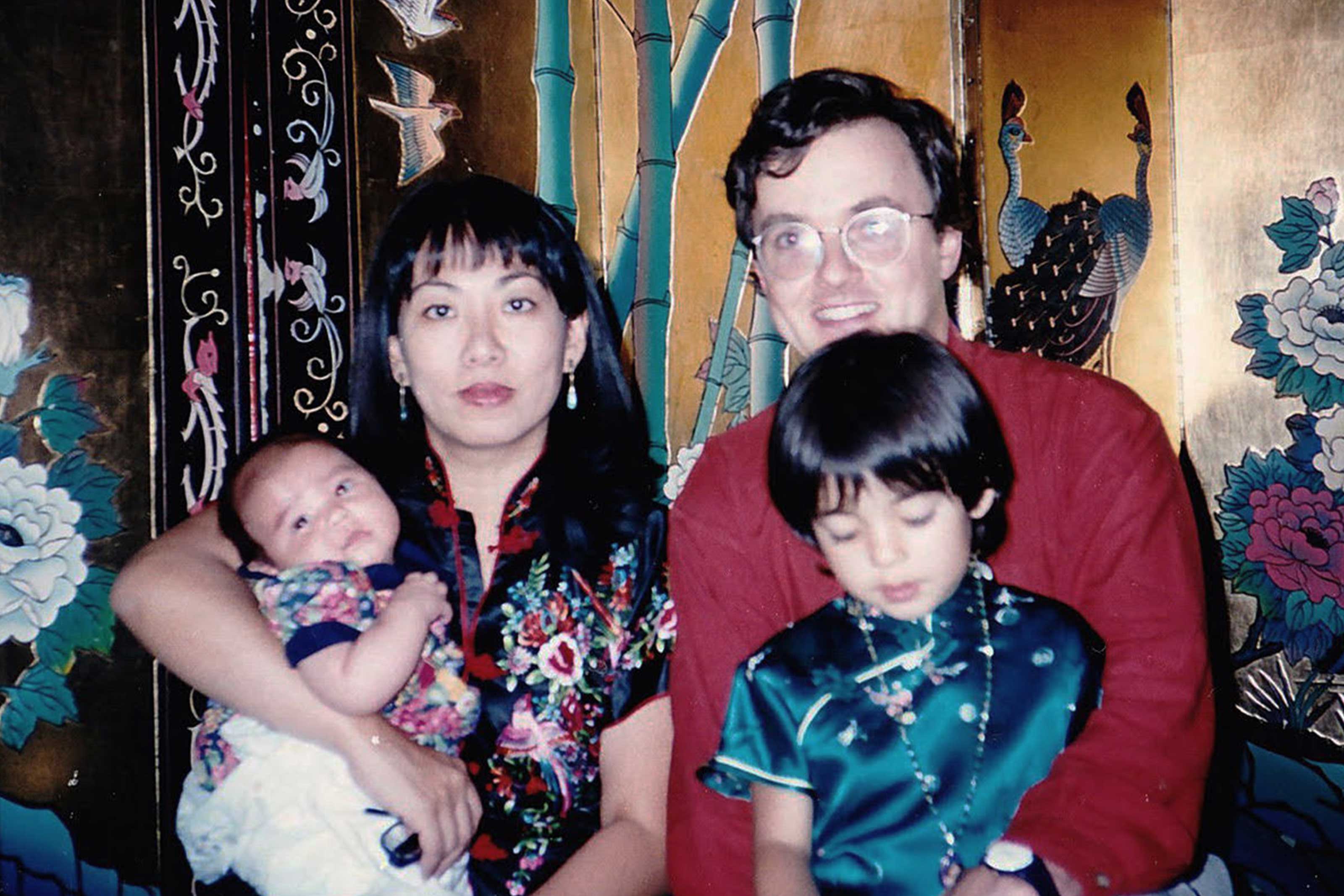

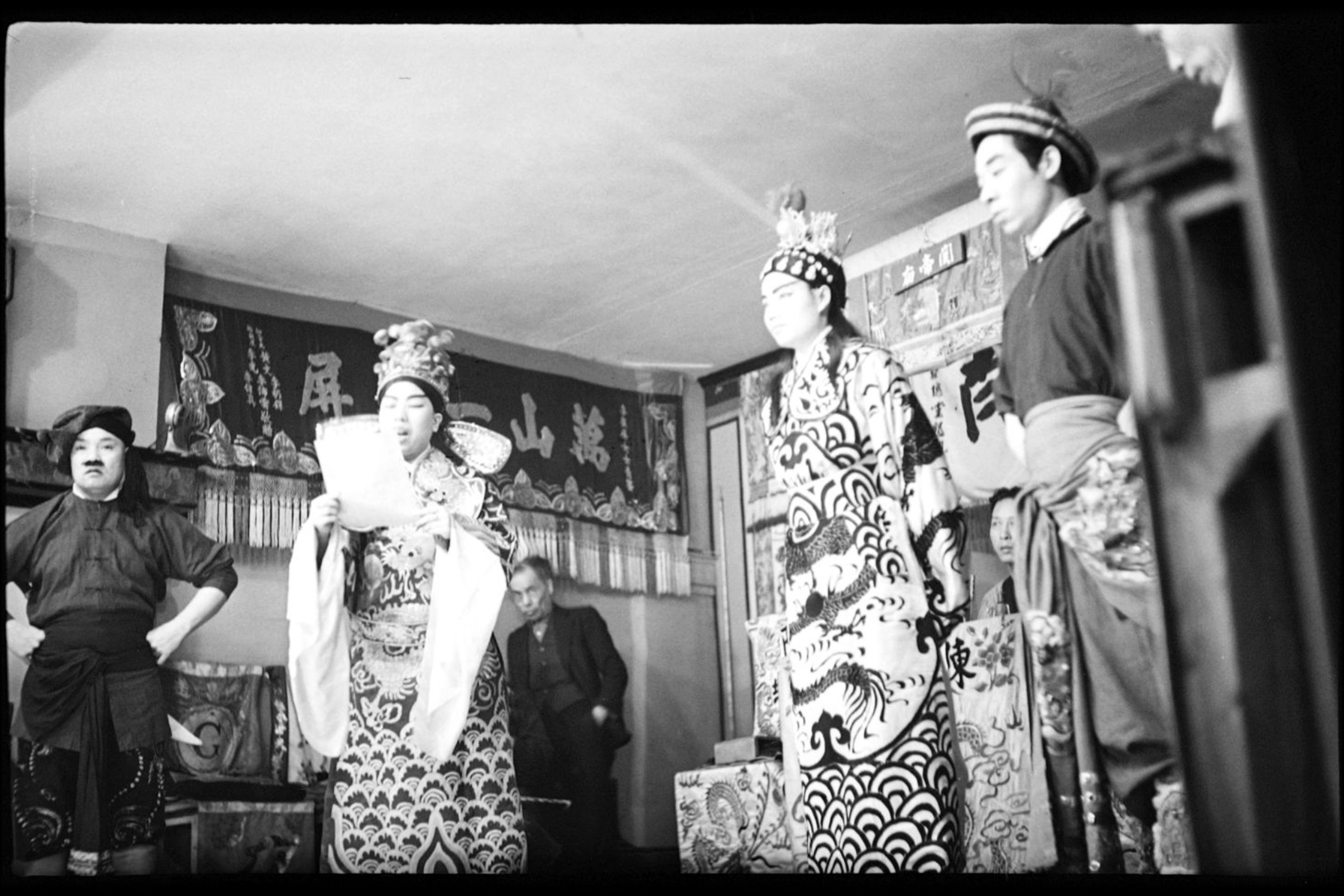

Amelia Wong-Mersereau grew up amid the loud cymbal crashes and back-dressing rooms of Montreal’s Cantonese opera. Her grandfather immigrated to Canada from Hong Kong in the 1960s, sponsored by Vancouver’s Jin Wah Sing Musical Association to teach the art form.

The family eventually moved to Montreal and her mother, a first-generation Canadian, found community in Chinatown as an artist establishing herself in the city.

“I was born into the backstage of Cantonese opera in Montreal…. I consider myself very privileged to have had this kind of access, especially as someone who is of mixed ethnic background,” she said.

While Wong-Mersereau struggled to find her identity straddling two cultures, she found home in the opera, housed in a restaurant in a nondescript commercial building along the main St-Laurent Boulevard strip.

“I went to Chinese school for a few years, but again, as a mixed person, I never really found my place. So I didn't really pursue learning the Chinese language, but always had access to the very rich world of Cantonese opera, which is alive and well today in the city.”

She joined the working group that has pushed to save the soul of the neighbourhood and preserve what remains. And she deeply feels a sense of urgency that is pervasive in today’s Chinatown.

“I think when people want to know why Chinatown matters, why we shouldn’t take it for granted anymore; it’s because if we lose this historic neighbourhood, we lose a massive part of this city,” she said.

“So much gets invested in neighbourhoods like the Old Port. You know, Place des Arts is this beautiful, vibrant place. I think Chinatown needs to have the same treatment because it is essential to not just people of the Chinese or pan-Asian communities of the city — it’s important to many cultural groups.”

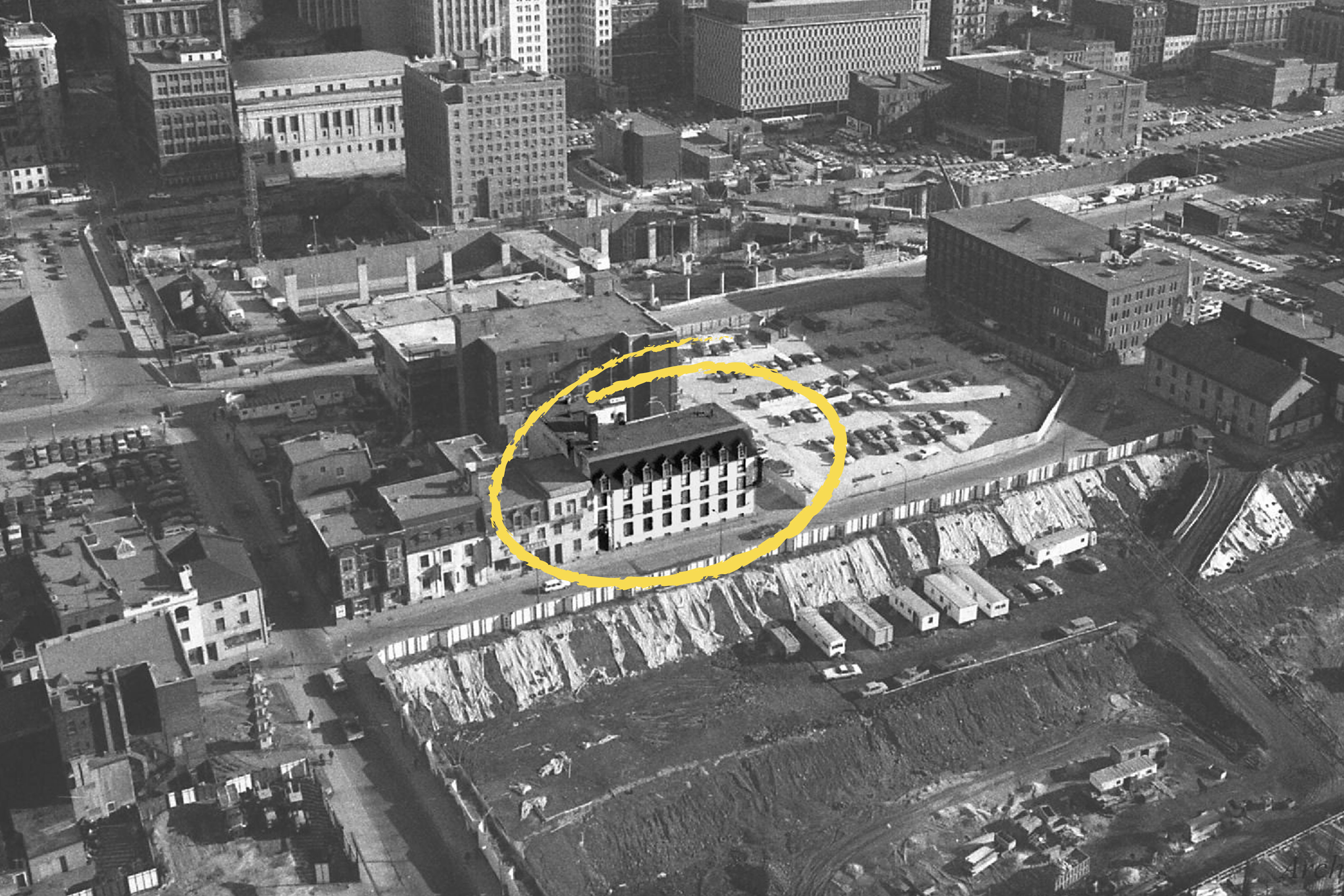

For decades, Montreal’s Chinatown has existed in the middle of a city trying to find an equilibrium between new and old. That meant the physical size of the neighbourhood shrunk as bigger developments moved in and a modern city emerged around it.

The federal government expropriated land to build the massive Guy-Favreau office complex, boulevards were widened, highways added. Multi-unit buildings went up and the massive convention centre moved in. Displaced businesses relocated to set up shop in clusters in Brossard and along Ste-Catherine West.

Victor Hum

Former president of the Hum Family Association

Inside the Hum Family Association, the walls are adorned with black and white photographs of the immigrant founders of the community.

“People worked really hard just to chip in and buy these properties,” said Victor Hum, the association’s former president.

The founders paid a little more than $10,000 for building in 1922, an astonishing amount when you consider how difficult it would have been to earn and save that amount of money. They still own the building, but many neighbours and other long-term property owners have sold.

“We’re getting smaller and smaller as we go on,” said Hum.

The family associations in Chinatown were one of the driving forces behind the building and preservation of the neighbourhood. Members raised funds and opened their businesses here. They established the Chinese youth centre, welcomed newcomers and served as gathering places.

Now, after struggling through the pandemic, residents and businesses are facing eviction notices or the threat of looming development. People worry elders and family-owned shops and restaurants could be victims of that gentrification, with rising rents forcing them out of their apartments and commercial spaces.

Without the historical protections of its Old Port neighbour, many fear the Chinatown that served as a foundation for so many Chinese and pan-Asian Montrealers could dissolve into the developing city.

“It takes a lot more than just a few of us to speak — it takes a lot of Montrealers, Quebecois to realize what’s going on in Chinatown and to save Chinatown,” said Hum.

The city has a multiphase plan for the neighbourhood that includes addressing both the built and cultural heritage. But many say it doesn't go far enough — or move fast enough — to save the soul of Chinatown.

Valérie Plante, of Projet Montréal and the city’s sitting mayor, says the city can only do so much to protect the built environment in the neighbourhood. They’ve invested in a working committee and a plan to promote businesses and encourage more activity, but ultimately can’t tell developers what they can and cannot do with their properties.

Plante says they want to work with developers to ensure they respect best practices and the expectations of the community.

“On top of that, we need the province to help us to say, ‘OK, this building, for example, is a protected one. Nobody can demolish it … or nobody can alter this or that.’”

Movement Montreal, the new municipal party fronted by Balarama Holness, is proposing a plan that includes beefed up zoning laws to prevent gentrification, mandatory consultation with businesses and stakeholders on development projects, and the establishment of a registry for Chinatown’s small businesses to offer rent and wage subsidies

Ensemble Montreal, another municipal party led by Denis Coderre, did not return requests for comment on the future of Chinatown. Their platform does not specifically address development in the neighbourhood, but it does outline measures to strengthen the public consultation process in the city.

Jean-Philippe Riopel

Chinatown resident and neighbourhood advocate

Jean-Philippe Riopel has lived in Chinatown for more than 20 years. His father was one of the first beat cops in the neighbourhood, and while he’s of French-Canadian descent, he's become an advocate for the neighbourhood that has adopted him.

“The people around me, the people from the community, they welcomed me,” he said. “I’ve been to 59 countries so far, but there is no place on earth that I could call home. My home is here.”

He gives historical tours of the neighbourhood and lives in one of its oldest buildings. He’s literally dug up artifacts from the neighbourhood’s past with his hands from his backyard.

In January of this year, he learned his building had been sold to a developer.

“There is absolutely no doubt that if these buildings are destroyed or if they keep only the facade or part of these buildings, it’s a community that will be destroyed,” he said.

“Do we want Montreal to be all facade and new concrete towers behind? I don’t think that’s what Montreal wants, and that’s certainly not what I want.... We will lose something that is amazing, that we’ll never have again.”

The same developer, Hillpark Capital, has acquired a number of historic buildings in the neighbourhood, including the one housing Wings, the oldest company in Chinatown. Founded in 1897, the family-owned business still makes noodles and fortune cookies out of the De la Gauchetière factory.

In a statement, Jeremy Kornbluth, of Hillpark Capital, said there are “no official projects planned” for the properties since there’s currently a lease in place with the previous owners. He did not say whether he had been contacted by the city or province to discuss preserving the buildings’ heritage.

Riopel worries that without legal heritage protection, there is nothing to hold developers accountable. He and a friend started a petition addressed to the Quebec National Assembly, calling for legal heritage status to be bestowed upon the neighbourhood.

Quebec’s heritage ministry says it’s participating in the city’s working committee, but has not announced plans for any heritage protection for the neighbourhood or its buildings.

Ultimately, advocates say, Montrealers need to understand there is more to Chinatown than dim sum and bubble tea; its loss would deeply scar the city and they need to up the pressure on those who have the power to preserve it.

Most acknowledge that doesn’t mean freezing the neighbourhood in time, but adapting the offering and attracting new businesses and investments — without the threat of writing over what has been long been.

The risk of losing the cultural touchstone and the “threat on that identity” has attracted many young Asian Montrealers to fight for its preservation — even if they don’t speak the language or have much personal connection to the neighbourhood, said working group member Walter Tom.

Seeing the younger generation rally and bridge the gaps both with elders and the larger Montreal community has given them hope that the cry to save the neighbourhood hasn’t come too late, he said.

But time is running out.

“For many Asian Quebecers, we are a minority within a minority,” said Tom. “We’re racialized communities, often speaking diverse languages — but we’re also within Quebec, a French-speaking province.”

“And so this is why this Chinatown is so unique. Because there's a whole amalgamation of different joie de vivre.… It’s not just one community, but many different communities [and it] is really our home.”

Amelia Wong-Mersereau