February 9, 2021

WARNING: These stories include details about domestic violence and child sexual abuse that may be triggering for some readers.

Liz’s childhood memories are spotty, but what she does remember is impossible to forget.

She says she watched her father get charged with stabbing her mother; she remembers frequently getting into fights at school and shoplifting; and by the time she was 12 or 13 she was doing sex work. She raised herself and always felt she was “bad,” she says.

“When I was a kid, I always knew I was going to be a drug addict. I always knew,” said Liz, who grew up in Ontario. The CBC is not using her real name to protect her privacy.

Now, decades later, living in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, it seems obvious to her that a traumatic childhood set her up for a life of addiction to crack cocaine and heroin and the emotional pain of losing custody of her own daughters.

Dr. Vijay Seethapathy, a psychiatrist and chief medical officer with B.C. Mental Health and Substance Use Services, says research has clearly connected trauma, mental illness and addiction, especially among women.

"This is not a new concept...we've been talking about this for close to 20 years now, said Seethapathy, speaking to the issue on CBC's The Early Edition.

He said when some people talk about treating addiction, they often speak more about healing the body than they do the mind.

"If you treat one area, particularly the addiction alone, leaving out there is mental illness and other social and societal issues, then the outcome, the effect of what you want to get, is not desirable," said Seethapthy.

The big question for places like B.C., where more than 1,500 people died from drugs in 2020, is what do we do about that and how do we help people heal before they die or hurt the people most important to them?

Liz and the three other women profiled below told their stories to the CBC with support from the WISH Drop-In Centre, an organization supporting women involved in street-based sex work.

WISH compensated them for their time, expertise, and the emotional labour it took to share their stories.

“Things always sit in the back of your [head]. You always remember everything,” Liz said. “And even though sometimes you pretend, you’re just pretending.”

‘Mommy, please let me come with you’

By age 19, Liz says she was married to a man she describes as a big-time drug dealer. Soon they had two daughters and a nice house. But she knew eventually they’d get caught.

When that day came, she says she was camping with her daughters. Liz breaks down when she talks about losing custody of her children.

“[One of my daughters] was standing there shaking and [said], ‘Mommy, please let me come with you,’ and they were taking her away from me,” Liz said through tears. “I miss them.”

Liz’s daughters are adults now and she doesn’t speak to them often.

She now lives in one of Vancouver’s downtrodden single room occupancy hotels with a mini-pitbull named Molly that receives all her love and care. Since Molly came into her life, Liz says her drug use has declined and she takes better care of herself because she feels she needs to be responsible.

She also wants to feel loved.

“Dogs give me such unconditional love,” she said. “They really do.”

‘I don’t have a problem being a parent. I have a problem with an addiction.’

Avery Grey called government social workers for help when her addiction was at its worst and she felt she couldn’t care for her children. Avery — CBC is not using her real name — says she headed off to rehab hoping to be able to become the mom she always wanted to be, a housewife who did bake sales and volunteered.

“To my understanding, [my kids] were coming back to me,” she said, her voice cracking. “I still don’t have them back.”

Avery says her problems started as a child in Calgary when her mother, who had an alcohol addiction, would verbally abuse her, calling her words like “bitch” and “whore.” By age 12, Avery was running away to stay with friends and family in a smaller community outside the city where she said everyone was loving and accepting, and some were using recreational drugs.

She says she first tried the drug ketamine, known recreationally as 'Special K' when she was 14. Throughout her teens, drugs were fun, social and helped her lose weight. She used recreationally until her early 20s.

Then, after she had her second child, Avery said she found herself using more and more until she was spending hundreds of dollars each day on cocaine but couldn’t find the money to buy her kids milk. She recalls having explosive and sometimes violent fights with the father of her children.

In an effort to get her kids back, she says she was mostly off drugs for five years, but had three relapses. She lost all her chances to get her kids back from government care for a laundry list of reasons, in part, at least, because of those violent fights and failed drug tests.

She says she found it too hard to live in the same city as the kids she couldn’t see, so she moved to Vancouver. She spent some time in a tent on the streets of the Downtown Eastside, disgusted by the rats and shocked by the level of addiction and homelessness she found.

“If I [saw] this as a child, I would have never, ever touched drugs,” she said. “But I only [saw] the cool people using drugs, so that’s what I wanted to be.”

Now that her kids are not in her care, she has no reason to stop using drugs, she says.

“It’s hell,” she said. “It’s completely taken everything from me.”

Legacy of abuse in government care

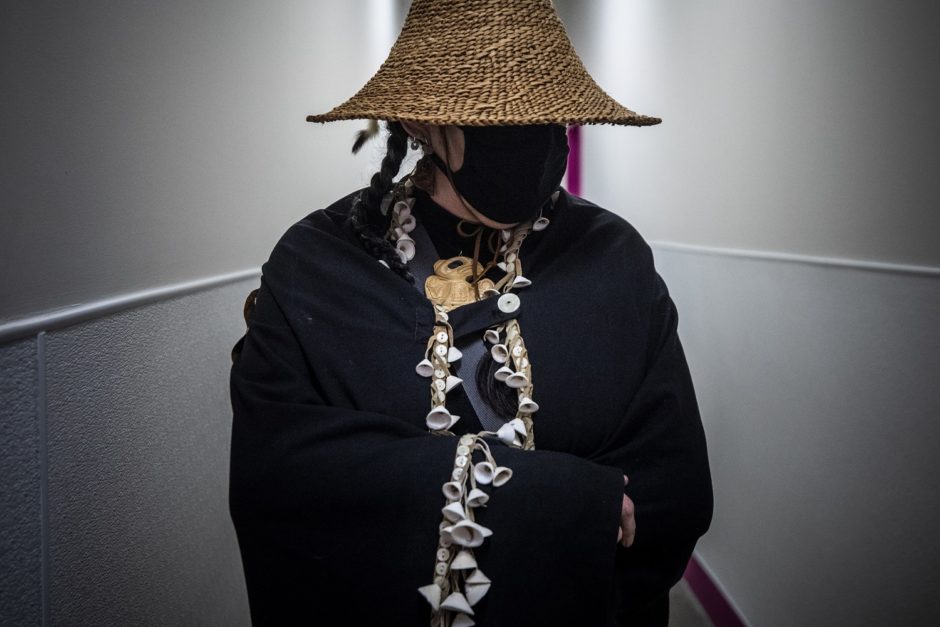

T’s story also illustrates how trauma and addiction can pass from one generation to the next.

She was five years old, growing up in Haida Gwaii, when she was forced to attend Indian day school, where she says she was abused — physically, mentally and sexually — for three years.

“I didn’t even know the word for sexual abuse,” said T, whose name CBC has agreed to withhold.

By the time she turned eight or nine, she was taken from her family as part of the Sixties Scoop. She says she was sent to Albertan farming families, where she was sexually abused by a so-called foster dad and his sons.

It took a horrific toll.

“I couldn’t really concentrate in school. There wasn’t any resources for us. That’s why I took it out on alcohol,” she said.

T worked as a nurse and eventually moved to Vancouver. She says she wanted to give her own children a safe upbringing. But her partner was struggling with his own alcohol addiction and physically abusing her. So she took her children and left.

She says she struggled as a single mom working and going to school. Certain smells started to trigger her, and her own alcohol use spiralled out of control until her children were taken into ministry care.

“I wanted my kids back, so I fought [against] myself,” she said of her decision to get help.

In the years since, she has been bothered by what she describes as the naivete of some non-Indigenous counsellors and other officials she’s had to deal with, who don’t convey a deep understanding of the government’s role in abusing Indigenous children.

For T, a crucial step was getting help from Indigenous counsellors who understood how her personal experiences of trauma were part of a bigger system of oppression.

“To this day, I give thanks to them for my self-esteem,” she said.

Healing is a daily battle. She says she’s working hard to help her daughter, who is struggling with addiction on the streets, and her granddaughter, who is a child in government care and T suspects is being sexually abused.

T says she has reported her suspicions of abuse to the provincial ministry.

“She had all the signs. Same thing happened to my daughter and I [saw] the signs. And it happened to me,” T said.

According to the Canadian Centre for Child Protection, signs a child has been sexually abused can include: learning difficulties, emotional imbalance, change in appetite, trouble sleeping, self-harming and physical ailments like headaches and chronic pain.

In a statement, B.C.’s Ministry of Children and Families acknowledged the trauma Indigenous children and families have faced and says it’s committed to changing this. It says anyone who suspects a child or youth is in need of protection has a legal duty to report those concerns to the ministry, a delegated Aboriginal agency, or their social worker.

The right counselling support at the right time was key for Mikayla Cadger.

Growing up in the Maritimes, Mikayla was Mikayla on the inside. But to the world, she was a boy with a strong physique. Her love of dressing in her mother’s clothes and other signs that she wasn’t the football-playing son her dad desired sparked fights between her parents.

Mikayla’s world started to fall apart one day when she was 14, when police officers rapped on the family’s front door. They handed Mikayla her mother’s teeth and her rings and announced that her mother, a medevac nurse who worked in the North, had died in a plane crash. Mikayla had lost the only person in the world who accepted her for who she was.

“I remember falling to the couch and screaming into a pillow,” Mikayla said. “I couldn’t speak for a few days afterward.”

Soon, Mikayla was using drugs and skipping school, she says. She headed west to Vancouver, curious about the city’s more active LGBTQ scene.

She says she got a job as a no-nonsense bouncer at what she describes as a “biker bar.” But under that rugged exterior, Mikayla would wear panties.

Addicted to opiates, she eventually tired of going through withdrawal on an almost daily basis. She got herself on methadone and started to work on the “why” behind her addiction.

“It’s a hole you’re trying to fill, and it very often has to do with childhood trauma,” said Mikayla.

With a counsellor she came to trust deeply, Mikayla says she unloaded the burden of her grief over her mother’s death. Eventually, she entrusted the counsellor with another big secret: selfies showing Mikayla all dressed up in women’s clothes.

“This has been going on for 30 years,” Mikayla told the counsellor. “And I’m sick of buckling under the weight of it.”

The road to come out fully as a trans woman has not been easy. Mikayla says she has been attacked and beaten, her home was spray-painted with derogatory words, she’s misgendered almost daily, and she has struggled to find someone who loves her for who she is and doesn’t fetishize her. But life today is so much better than before she got help.

“I spent so many years hating myself but the world was OK with me. Now I finally love myself and the world’s become a lot harder. But I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Tap here to listen to these women’s stories in their own words, and to hear an expert discussion about the connection between childhood trauma and addiction on CBC's The Early Edition.

If you live in B.C. and need support for substance use, call the province's alcohol and drug information and referral service toll free at 1-800-663-1441. For Vancouver residents, dial 604-660-9382.