September 16, 2019

It was 2017 and Richard Driscoll was certain his life was finished.

He'd tried to change his life, one filled with drug-fueled crimes, for years.

Yet every time, he'd end up back in a place he was far too familiar with — Her Majesty's Penitentiary.

"It turned into me walking around the range — a unit in the pen. People just walk around all day doing laps because there's only 50 feet one way and 20 feet the other," Driscoll said.

"You walk around like a fish in a fish bowl."

Walk, stretch, work out, shout at the guards, be shouted at by the guards.

Repeat.

To cope, people cry, people fight, people do drugs, people draw.

"Me? I didn't know I could write poems. I was counting the range tiles, the floor tiles. And I thought, how many floor tiles does a range hold?

"That turned into me looking out the window … I was looking at the boathouse. I could see people down there, people talking, dogs playing. I thought, 'Do they even know we're here?'"

That's how Richard Driscroll wrote his first two poems.

The Boat House

What a treat to look out and stare

at free people gathered round without a care

The boat house is the place where victory is

cheered

Do you think they wonder that we are here?

Goals set and team strong, they get to it

While we get fed and growl over our porridge.

The blood and fights we're up all night

While at the break of dawn they're rowing on.

Regatta is the day for which they train

Too bad, we couldn't swap places and they

take the blame.

We get ready and prepare for court

The boat house is here giving her support.

Victory.

Driscoll has a history with the lakeside penitentiary. The darkest recesses of it.

He's been to the SHU, the Hole — all the prison acronyms you can think of — and federal prison.

In a way, that was a good thing.

Driscoll accrued a certain amount of respect through his jail time, which allowed him to go freely to the chaplain without there being accusations of informing or snitching.

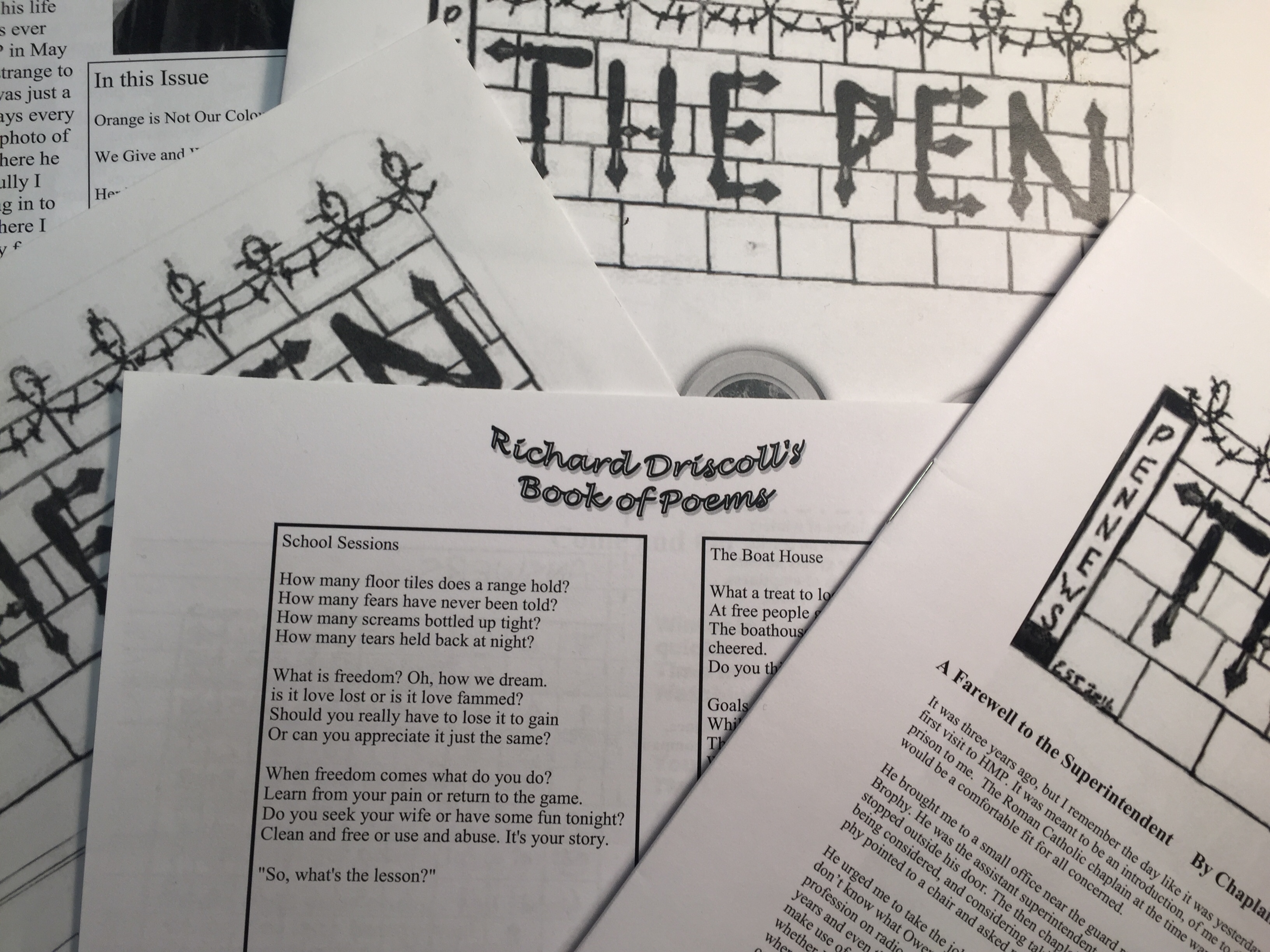

A newsletter by the inmates, for the inmates

Former journalist Gerry Phelan was approached and asked to start a newsletter when he started as the Roman Catholic prison chaplain five years ago.

He was hesitant at first, but once he agreed, one thing needed to be clear: "It had to be theirs, not ours."

"As we talked about all the good that was going on at HMP, stuff that we saw that we knew the public wasn't seeing, we decided that we'd make an attempt."

Four inmates came forward at first. Then dozens suggested a name and graphics for their newsletter.

The Pen was born.

Inside the black and white, neatly stapled issues are poems that detail regret and confessions. Photos celebrating behind-the-walls accomplishments.

When two inmates died at HMP, there were articles on that, too.

Hand-drawn Sudoku puzzles contain words like "methadone," "lockup," "pondside" and "respect."

The latest issue of the Pen delves into what inmates want in the newly promised prison: eye doctors, pen pals, fresh fruit, a garden to grow vegetables.

The talent of the contributors didn't come as a surprise to Phelan but the brutal honesty was.

"They were willing to open up, were willing to share the bottoms of their souls with other inmates," Phelan said.

"This guy was signing his name, he was on the range. You kind of have a rep to live up to on the range."

There are challenges, of course, like any publication.

For one, the newsletter committee is always in flux, depending on how lengthy the members' sentences are.

And there's the cost — several churches pitch in to pay $400 to $500 per issue.

Driscoll wasn't one of the first inmates to raise his hand to write for the newsletter.

It was an opportunity born of discussions he had with Phelan.

Given his poor reputation in the penitentiary, Driscoll said, he wasn't allowed to go to programming.

He was, however, able to see the prison psychologist and RC chaplain.

"While I was up with Gerry, I started writing the poems. He said, 'Why don't you submit them to the Pen newsletter?'"

From there, he went from contributor to newsletter committee member. Driscoll and others would sit around a table discussing which articles they should cut or include.

"We would talk about what the management of the prison would allow or not allow ... how it would look in their eyes and basically get a newsletter together that would get passed, not be delayed and be good for the inmates."

Driscoll drew inspiration from things around him.

The mundane: he jokes he must have written six poems on making his bed.

And the grim: the Miller Centre, which towers over nearby buildings like HMP is a constant reminder of death and suffering.

Trading Tears

Life wasted with all these years done

We sit here and wonder how come we're not gone

While people in the Miller Centre cry for life

A sad comparison to think about every night.

Trading tears like war torn vets

While they sit and die with cancer in their chest

All our families weep and cry

Praying for these moments to pass us by.

Imagine the children with no chance at life

What their families will do to make it seem bright

All we do is drugs and die

Or keep on picking up prison sentence time.

Donate those years back to save those kids

They then wouldn't be a waste, just a blessing

My fate is my own, as yours is yours

Think of those kids next time you do a score.

Life is a privilege, when you have none to live

Precious moments outside and not in

As those people die we should reflect

My life is worth something, I want to make it the best.

A prison wedding

He started getting feedback from staff and inmates.

Driscoll was doing something worthwhile. Something that helped.

"[I went from] Richard the guy you don't want to mess with, or the guy you wants to fight, to the guy who just wrote a poem that made me feel good about myself or helped me cope with being locked in my cell today.

"If I wasn't writing poems, who knows? I could have been involved in an incident, or picked up more time. Writing helped me maintain mental sustainability."

In 2019, Driscoll became a character in the newsletter he helped build.

Page 8: Wedding at HMP; A First; In Recent Memory.

"The groom was neatly dressed in a black shirt and pants, and a white tie. The bride wasn't wearing a wedding gown, but her dress and shoes made her beauty shine in this otherwise grey place," the article said.

Driscoll went all the way to the justice minister for approval after requests to get married inside HMP were denied by prison officials.

Another positive story worthy of The Pen.

It has been months now, and Driscoll has no plans to return to the penitentiary.

On this sunny August day, he's looking at the boathouse from a different angle: on a park bench perched next to Quidi Vidi Lake.

"My embodiment of freedom is sitting here on this bench, looking at the boathouse. It hurts my heart looking at the pen. But now it's all positives."

"The pen is just the pen. It's the past."

Phelan and Driscoll still meet up, now able to to sit and have coffee as friends on the outside.

"I've seen him grow, poem after poem after poem, express himself, express his want to change his life, to improve his life," Phelan said.

"And then to see the life take effect and manifest itself on the outside. That has been internally gratifying for me."

Driscoll has approached the Writers' Alliance of Newfoundland and Labrador to help him improve his writing, and he is planning on taking photography courses.

Though, he admits there has been a hurdle in his writing; the negatives he once used as fuel have dissipated and have been replaced. Hope, joy, happiness, change.

His wife is now pregnant. They're expecting a baby girl.

Poems may soon turn to nursery rhymes.