December 1, 2019

Amelia Curran is worried. It’s January, it’s cold, and she’s on a mission — to learn about women who have traded sex for survival, and then to write and sing a song about what she discovered.

She knows what she doesn’t want to do: pen lyrics about the lady in fishnets who’s leaning into a car on Long’s Hill in downtown St. John’s, or the teenager in a matted faux-fur vest and smudged eyeliner on the sidewalk, spindly legs ending in spiked heels. After all, the last thing everyone needs is a hackneyed tune capturing everything she’d always been told about people in the sex trade.

But the acclaimed St. John’s-based singer and songwriter — who accepted a CBC commission to write about the women she is about to meet — doesn’t know what to expect.

She pulls on a shirt advertising her feminist bent, preparing for a heavy conversation between herself and six women who’ve seen a lot in their years.

Determined not to come across as judgmental, but still anxious about her status as an outsider, she’s hoping to welcome whatever comes her way. Curran’s large blue eyes and impish face, paired with an open demeanour and calm voice, might do the trick. When she enters the room, she’s armed with notes of what to say to fill lulls in the conversation, just in case nobody feels like talking.

Within seconds, Curran learns all her worries were for naught.

“They’re not wilting flowers,” she recalls months later with a wry smile.

They sit across from each other, jovial, comfortable, already chatting. One woman not only liked school as a kid, but homework, too.

“My life was always a bit of a circus, so I leaned into it and actually joined the circus.”

Another is vocal about her hatred of shoes; she slips them off whenever the situation allows. A third mastered the art of saying the alphabet backwards; a fourth, sitting close by, waits eagerly all year for autumn just so she can kick through the leaves.

Then there’s Tiffany Halliday. “My life was always a bit of a circus,” she says, “so I leaned into it and actually joined the circus.”

When words like “prostitution” are thrown around, it’s easy — all too easy — to think of scathing stereotypes and rigid clichés. Minds turn to runaways and orphans, young women down on their luck. “We have all these ideas given to us in the media, in movies and TV shows,” Curran says. “And even knowing better, you can’t help it. It’s in there.”

But these women are launching nursing careers, caring for children, studying for degrees. Today, all of them speak openly about the sex trade as people who’ve lived inside it. (Curran later described the conversation as being privy to workplace chatter, like she was a fly on the water cooler.)

Curran has an unusual task. As part of a CBC project, she’s writing a song capturing the ideas tossed around that room — painting a portrait of life in the sex industry with chords and lyrics.

Curran figures it might take a few days to write the chorus and come up with a couple of verses. Maybe a fortnight.

After six months, Curran finds herself still waging war on her notebook, grappling interminably with what she’d heard.

“That was a hell of a conversation,” she says gravely, reflecting.

Listen to Heather Barrett's documentary for CBC Radio's Tapestry:

'The game.' That’s what they call it

The conversation starts naturally. Nobody’s nervous at all.

On that January morning, soon after Curran enters a world largely unknown to her, one of the women laughs. It’s gravelly and free of anxiety. She doesn’t sound like someone who’s been through tough times. “You’re paying for sex one way or another,” she says with easy conviction. “Seriously, get over yourself!”

The others share her mirthful take, the gallows humour.

It’s not always bad, sex work. One of the women recounts that at her first day on the job at a massage parlour, the client’s eyes landed on her. Chosen right off the bat. Thrilling, she says; it stroked her ego.

Another didn’t know she was being exploited. At least not at first. Her boyfriend introduced it like a game they’d play with other couples. "The game." That’s what they call it. A nickname for the job, the life.

Some people in the sex industry create a second version of themselves, an entirely separate person, sometimes with a distinct personality or even a name — one to work, one to go home and make dinner for the kids.

“At first having two lifestyles is exhilarating,” one of the women says. But then you’re hiding it from friends and family. Johns notice you at Sobeys. The lies pile up.

Then there’s the fear. Constant and oppressive. The threat of death. Disease. Chaos. There’s also, one of the women says, the nagging feeling that you deserve it.

As the women trade stories, a common thread emerges: Getting out is much harder than getting in. And being in isn’t easy.

Another woman says bluntly: “It’s not like you’re waking up every morning going, ‘I love sucking dick for a living.’”

Mary Fearon wasn’t in the room that day. Fearon works at Thrive, a non-profit organization based in St. John’s, not far from the downtown core. She heard a recording of the conversation later, and it floored her. In all her talks with those women, she’d never heard them so frank — emotional, yet philosophical. “I heard the human voice,” she said.

“Once you’re out, what do you do with all that?”

Fearon heads the Blue Door program, which helps people exit the sex trade. She and other support workers hear a lot from the women inside: how they’ve been beaten, or escaped death, or left emergency medical care to tend to an addiction — scoring the drugs, taking them, then heading straight back to the hospital for treatment.

But when people in the sex trade speak privately to each other, she says, “they just reveal a different level of themselves … it just fills in a lot of those blank spaces that we think we know something about.”

Reassembling a post-sex trade identity, though — the long act of piecing together an existence after exiting the industry — is something they’re still figuring out. When someone’s “other self” is doing the work, one woman says, it’s hard to bring yourself back together. To empty the other compartment.

“Once you’re out,” another adds, “what do you do with all that?”

'They’re treated as the criminals'

Mel Brace might have an answer.

Brace survived exploitation. At 16, a man approached her in a bar, charming and flirty. He eventually became her trafficker. “He brought me nice places, bought me nice things, made me feel really, really special. Which is something I don't think I'd felt until then,” she said. “I think that's what kind of everybody wants to feel in life. So all the things that had been missing from my life, he filled in.”

Brace started off in love. Eventually, she became a target for his fists. Then, she was selling sex on the streets, turning to drugs as a distraction. Today, she works with Thrive, helping women adjust to working outside the sex trade and cope with realities often imposed on them against their will.

Recently, she’s found herself joining forces with a group she once feared, the police. She’s come to see they have a legal obligation to help survivors.

If only they knew how.

The beat cops who once reinforced shame are now — for Brace at least — a potential source of safety. This, she points out, is a feat considering not that long ago, Canadian law still put women in jail on prostitution charges. For most in the trade, cops were enemies, not friends.

“The women didn't feel like they could reach out to the police for things,” she explains. The relationship has always been strained. Handcuffs always at the ready.

Curran got a sense of that, pointing to stories of officers showing up in massage parlours in uniform. “These women who are not breaking the law — they’re looked down on,” she said. “They’re not doing anything illegal but they’re treated as the criminals.”

Haunted by memories of harassment from her days on the street — cruisers with intimidating cops behind the wheel, stopping to tell her to move along — Brace fought off apprehension before stepping into police headquarters earlier this year. She’d been asked to lead training sessions on the sex trade for frontline officers; her goal, to convey the gravity of their role as empathetic protectors.

Despite doing away with slides and notes — “I was just speaking from the heart for most of it,” she says — the meeting wasn’t unfolding as she had hoped.

“I didn’t feel like I was getting across to them,” she recalls.

Disappointment welled yet again.

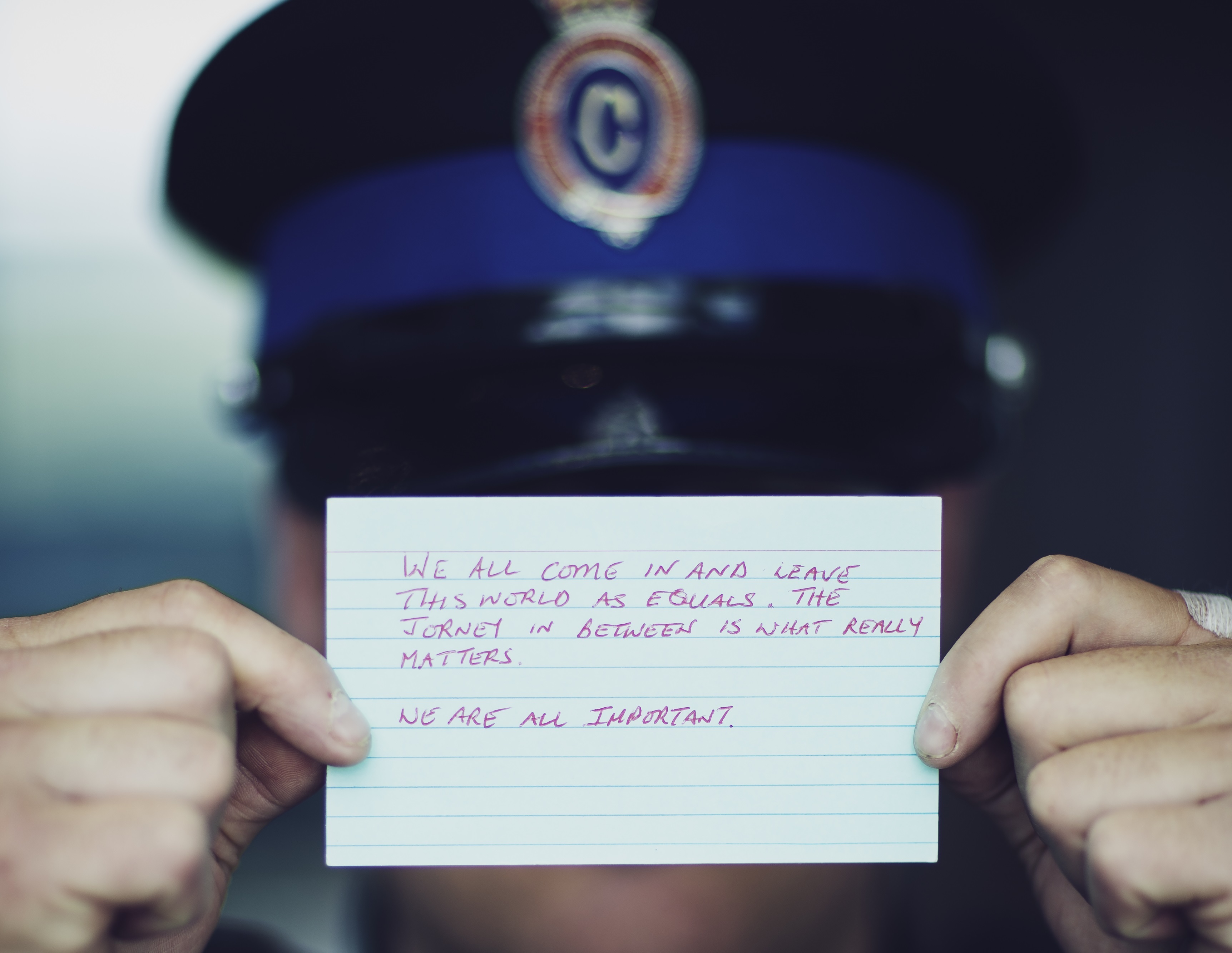

She handed out cards and markers to the rows of stony faces in front of her, a last-ditch attempt at reaching them. The officers took a few minutes to write down their thoughts. Gathering those cards as the room cleared, Brace thought, I don't think this went very well at all.

Back in her office, Brace sifted through their sentiments. What she saw astonished her.

“Just because we play on different teams doesn’t mean we can’t respect each other. I will listen.”

“Your story matters. Come talk to us if you need us.”

“We care about your well-being … I signed up for this career to try and make a difference.”

Brace was overwhelmed by the messages.

“When I read them, I was so impacted,” she says, “I actually started to cry.”

What a police chief has learned

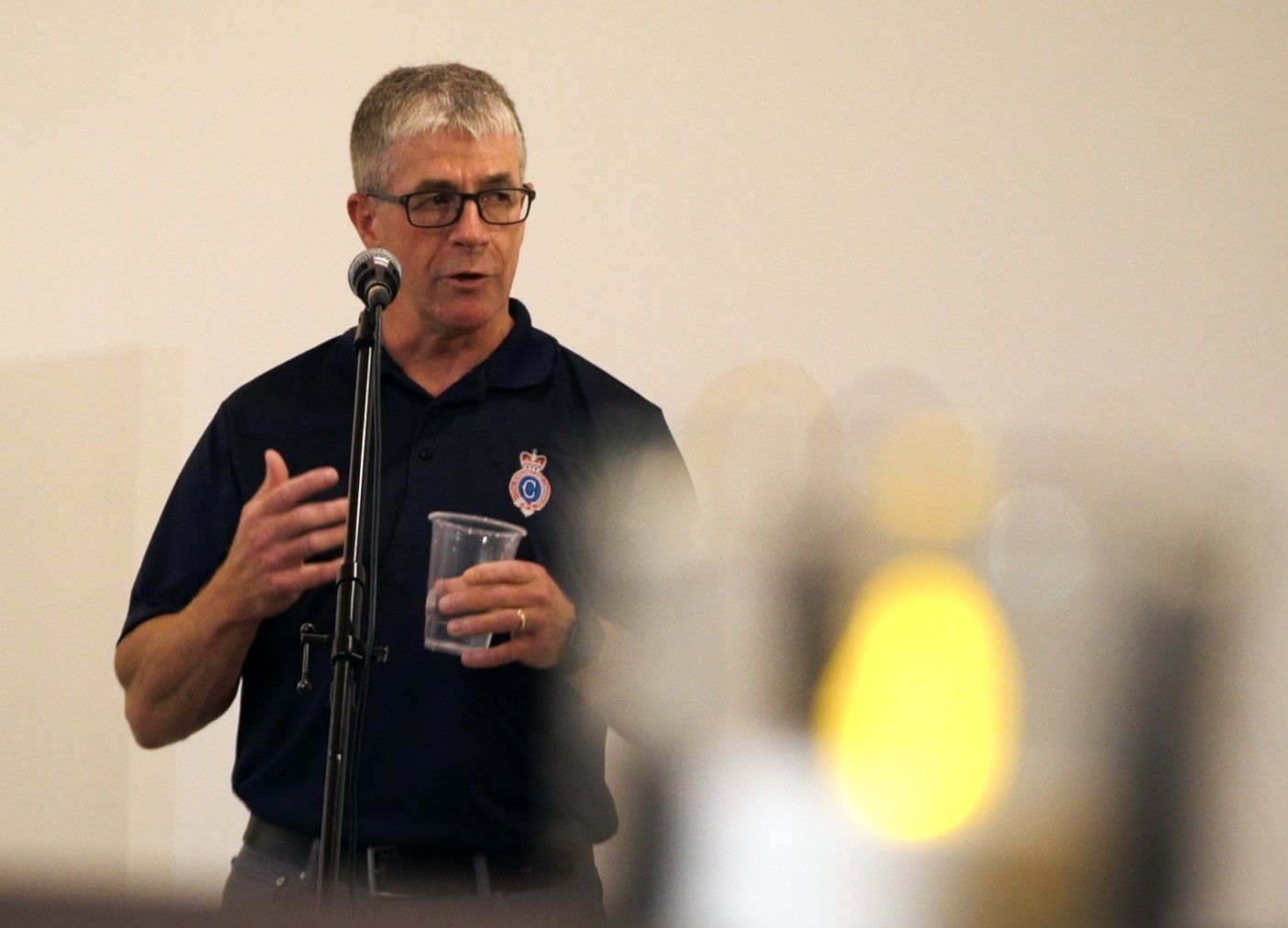

It's always been an awkward dance between people in the sex trade and law enforcement. RNC Chief Joe Boland can’t remember a time it wasn’t.

Should people selling sex be ignored? Arrested? Asked if they need assistance? Told to take their services elsewhere?

Brace has witnessed all of those approaches firsthand. Boland’s officers face a dilemma when it comes to managing the sex industry: how do you navigate, for instance, an early-morning call from a mom worried about violence coming from the brothel next door when the women inside aren’t breaking the law?

Some, they can’t do much about, Boland says. For instance, there aren’t any low-barrier shelters in Newfoundland and Labrador — that is, nowhere to drop a woman at risk of battery (or worse) in the dead of night, which means that sometimes the only option is the town lockup.

“The last thing that we want is incarceration of vulnerable people in our community,” Boland says. But when a system’s broken, people fall past the services that might have helped them — and they don’t fall past police. “They’re normally left for us to deal with.”

When he started as chief, Boland realized a segment of the population was “really crying out for help,” he says. He held numerous meetings in the community to find a fix. Opinions clashed over what to do. “I walked away from that thinking, we're perhaps no closer to a solution.”

No closer to giving those in the sex trade a safe way out, nor a safe way to stay in. No closer to balancing the freedom to choose sex work with enforcing human trafficking laws.

“The frustrating part has been how society has failed. How different levels of government here have failed,” he says.

But Boland’s learning. Mostly, and unconventionally, from survivors like Brace.

“We really haven't sat and listened to the people that have the experience,” Boland says. “And it wasn’t until we got to that point that we started to find inroads. We started to make gains.”

After Brace read what Boland’s officers had written, she started striking up conversations with cops. At one point, off to a meeting with Boland himself, Brace marvelled at how dramatically her life had changed. “I was driving around with the chief of police in the front of a police car,” she recalls. “I even had a moment where I went, ‘I need to take a selfie!’”

“In 37 years, I've learned in this business that we have to bring people to the table that have the experience. You know, it took me a long time to realize that.”

Boland and Brace now have an easy rapport, but it's taken some work. They’re colleagues with sometimes differing opinions, but a sense of empathy for each other.

Their work together has not been in isolation. Other officers have been building similar bridges with Brace and the women she works with; Brace even considers one RNC officer, Const. Chelsea Guinchard, a good friend.

“I’m able to tell women, ‘I know this cop, you should give her a call,’” Brace says, even if it’s just for advice or support.

Forging that trust, Boland says, meant treating those who’ve played the game, who’ve sold sex or been trafficked, as partners — that is, people who help guide policy instead of passively being affected by it.

“In 37 years, I've learned in this business that we have to bring people to the table that have the experience,” he says.

“You know, it took me a long time to realize that.”

Revealing truth in photography

It’s July. While Curran fights with the drafts of a song, Mel Brace mulls over what to do with the cards on her desk.

Then, an idea takes shape: those cards aren’t just insights into how police officers think — a glimpse beyond the badge — but conduits for a conversation that could play out in the public eye.

To make that happen, CBC brought the police and women together to pose — with their messages — for St. John’s-based photographer Dave Howells.

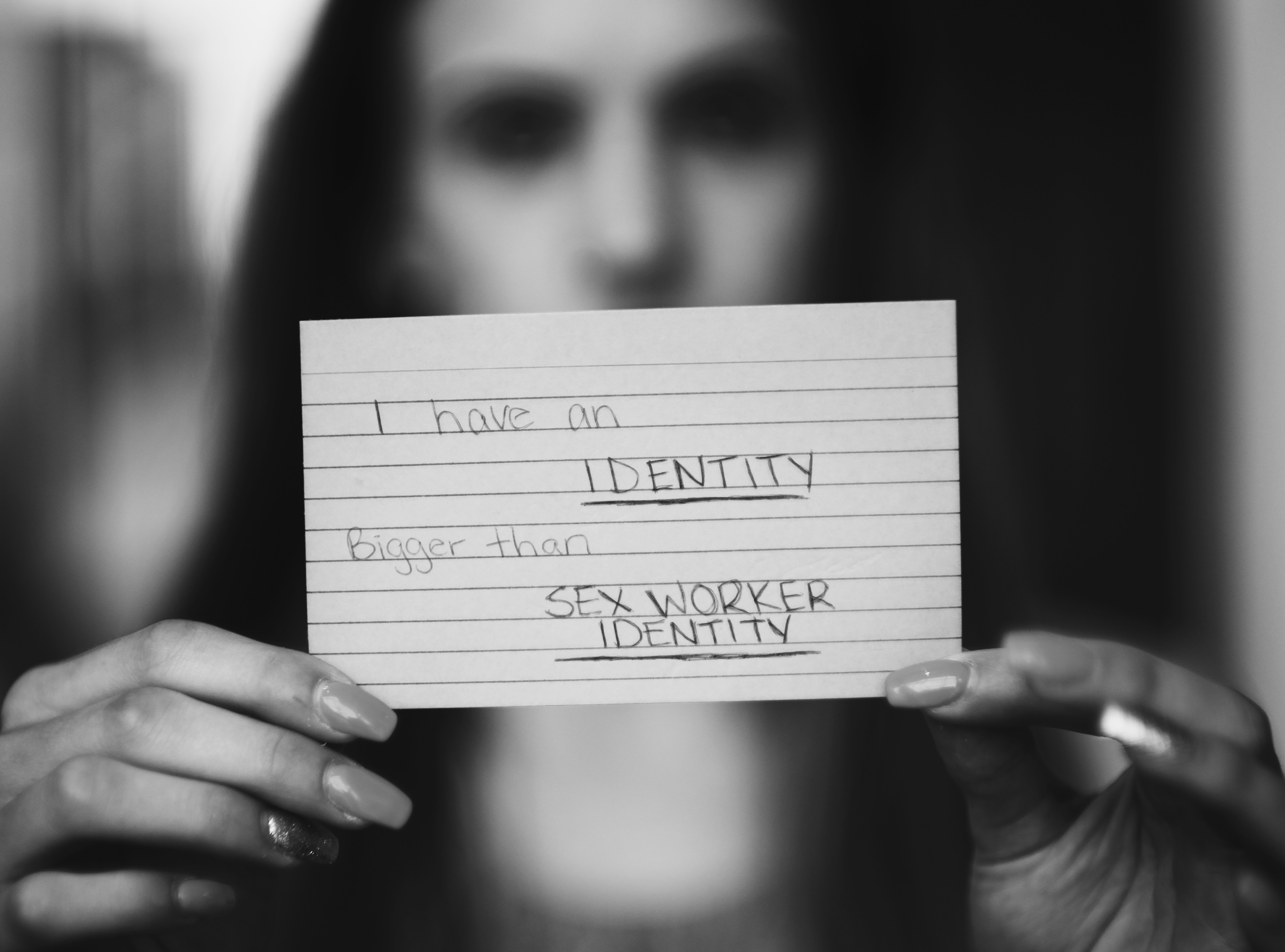

“You can’t tell who’s a police officer and who’s one of the women. And that’s the goal."

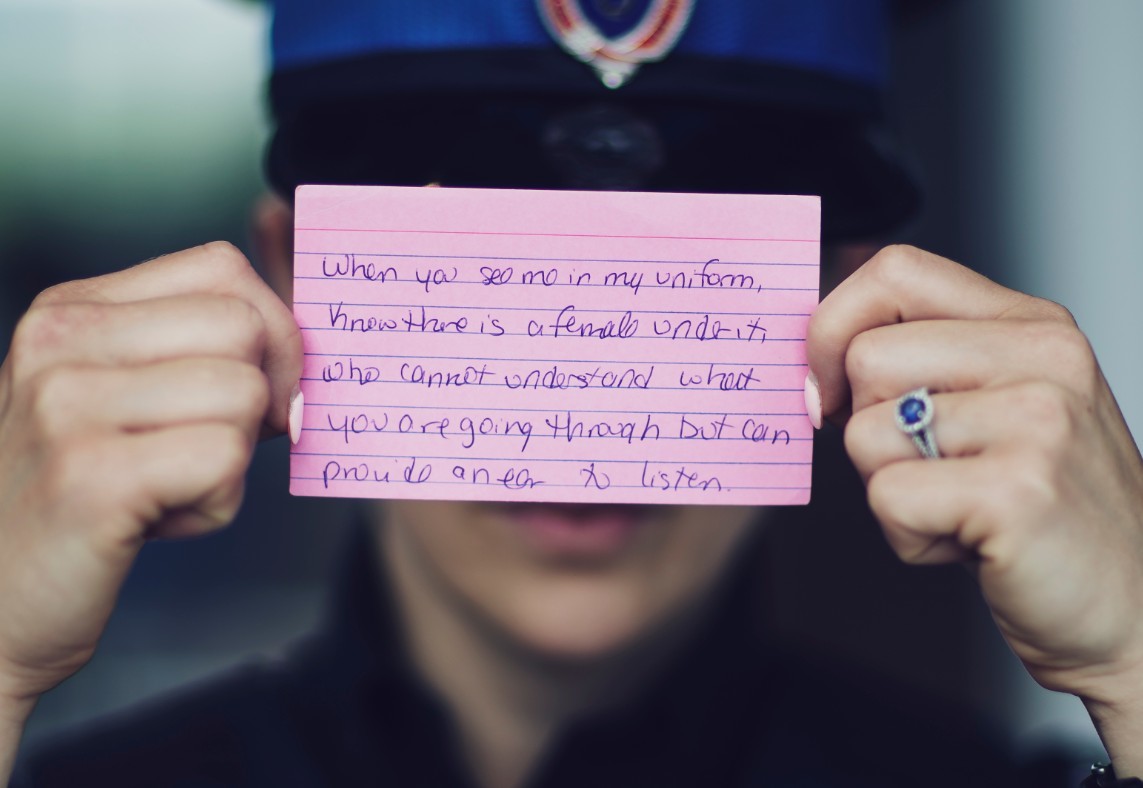

“When you see me in my uniform know there is a female under it, who cannot understand what you are going through, but who can who can provide an ear to listen,” one card reads. The officer holding it has short hair and a wide smile. Another, from a survivor, references her nursing career. “I take care of your mother and father, grandparents when you can’t.”

None of the cards have much at all to do with sex work.

Howells spotted that, too, while shooting the photos.

“If you look at all the pictures, you’ll notice one thing in common. It’s that all the eyes are the same,” Howells said.

“You can’t tell who’s a police officer and who’s one of the women. And that’s the goal — strip away the facade. We just have a human sitting in front of you. We are literally all the same.”

Howells wants the images to break down assumptions on both sides as a means of peeking into the underworld of the sex industry and peering over the fortress of the thin blue line.

How did the photo shoot turn out? Click the player below to see our powerful documentary, Wounded and Lucky:

Looking at the photos, Boland says they’re proof the sex trade has tendrils everywhere. Entering the industry, whether by will, deception or coercion, could happen to anyone. “It could be one of your children. It could be a friend of theirs. It could be a spouse.”

Boland points to a culture within the sex trade that’s shrouded in secrecy — at least, that’s the way it was for a long time. That’s why, he says, women calling cops just to chat is such a profound gesture.

And having them all pose for portraits? Previously unheard of.

At an unveiling of the photographs and Curran’s song at the Rocket Room in St. John’s this summer, Tiffany Halliday — one of the survivors Curran wrote about, and now a peer support worker — takes the stage.

“A year ago I’d have never been standing in this room. I’d never have been cuddled into Chelsea and getting some consolation hugs,” Halliday tells the crowd.

Brace expressed similar disbelief when she addressed the audience, much of it tearful. “Jesus Christ, I’m drinking beer with the chief of police and I don’t have handcuffs on!”

“I think for the women, it was really important for them to have an opportunity to see [police] as human beings,” says Mary Fearon, reflecting on that night. That is, cops as people who take off their uniforms at night, some of whom might lie awake worrying about what they’re doing wrong.

And for the survivors, revealing their secret selves — the ones they used to hide from the world — was a step toward figuring out a better system for those still tied to the industry.

“This is why we’re here,” Halliday mused. “We don’t want an ‘us and them.' We want to be a part of the conversation. And when there’s policymakers sitting at the table, making decisions that are going to affect people, you have to have those people at the table too ...you got to come to us and see what we need.

“And that’s exactly what this is going to foster.”

For months, as Mel Brace forges her odd new friendships, Curran tortures herself over her commission, lyric by lyric.

“My job is to communicate this somehow in an acceptable, arm’s length, accessible-folk-music way,” she explains.

“I wrote 50 songs ... I couldn’t get it right."

“Which is not your first thought — ‘I’m going to learn about sex workers and their experiences by listening to folk music.’”

She’s frustrated. She can’t write a ballad or lean on melodrama. It has to be political and personal, yet universal. She’d have rather written an essay than a song about the ideas exchanged that day.

“I wrote 50 songs,” she says. “I couldn’t get it right.”

Her dilemma hangs on a long-standing conflict. “It’s impossible,” she says, describing the tug between the competing concepts of female exploitation and woman’s liberation.

Curran’s not sure she’ll ever personally resolve that tension.

“I want them to be empowered and free to make these choices, but I want them to be safe and not abused and not manipulated,” she says. “I don’t know where these two things meet.”

A song emerges

After months of rough drafts and clean slates and changes of the season, Curran meets Brace and some of the other women for breakfast.

As they eat, Curran picks her moment, then pulls out her phone. “I have a copy of the song,” she says. “Do you want to hear it?”

The table falls silent, as ears draw near to listen to the melody and the words Curran has chosen.

And I don’t know about a sense of immunity

What doesn’t kill you leaves you wounded and lucky

I may be saying the things that shouldn’t need saying

...

A uniform that don’t fit

An accusation that she asked for it

A secret game, a still life counterfeit

At one point, the woman beside Brace reaches for her hand; she grips it tighter when Curran sings the chorus: "I want to live above the undertow." It’s a line that stayed with Brace, too.

“You kind of worry when someone takes what you say away to make something out of it themselves. You wonder if they're going to represent things the way you wanted them to,” Brace says. “But she captured a little something from every single person that was in that room.”

That synthesis — drawing together stories from different lives — narrates a specific kind experience. It’s not one lived by many, it’s but one that could be lived by anyone.

“Sometimes the only way for people to care about something is to see it happening to themselves,” Curran says about those lyrics, fervor creeping into her voice.

“We’re not that far from being a part of the game ourselves.”