March 8, 2019

When Susan Levi-Peters woke up and discovered blood smeared all over her clothes, she knew she had been raped.

Then 17, she was about to graduate high school and decided to celebrate with a few beers at a park in Elsipogtog First Nation, about 70 kilometres northwest of Shediac.

“Next thing I remember this man was on top of me, and I just was saying, ‘No’. And I blacked out.”

More than 35 years later, Levi-Peters, a former Elsipogtog First Nation chief, still doesn’t know if she had too much to drink or if her beer was spiked.

When she woke up in the passenger seat of a car the next morning, the man next to her kept telling her nothing happened. Scared and confused, she asked him to drive her to school.

Levi-Peters has tried to forget what happened. But it led to abusive relationships, alcohol, drug abuse and thoughts of suicide, which she has since overcome with the help of rehabilitation and the support of her family.

“At that time I was still a wounded animal.”

Not only did her history follow her into adulthood, it also crept into her career.

A First Nation chief

In 2004, she was voted chief of Elsipogtog First Nation, the head of a council of 10 men and two women. Her new role brought her into regular contact with the man she says sexually assaulted her.

“I wanted to throw up,” said the 53-year-old. “I wanted to beat him up.”

But Levi-Peters knew she had a job to do and issues she wanted to tackle.

“I had to not think about it at that time because it was not about me,” she said. “It was about our community.”

Levi-Peters was the first woman to become a chief in Elsipogtog. Her dad, Albert Levi, was chief for 26 years.

At meetings, she suspected some councillors voted against her because she was a woman, even if her ideas were for the benefit of the community. Her first year, council even voted to take away her salary, forcing her to live on welfare for six months.

“I kind of felt maybe they didn’t like the fact that I was a woman. Because the men that were in my opposition, were very masculine.”

But that didn’t stop her.

Levi-Peters and chiefs from across Atlantic Canada gathered in Woodstock First Nation one year for a meeting attended by Andy Scott, the Indian affairs minister at the time.

She tried to talk to Scott about Elsipogtog’s serious housing shortage but kept being told he was busy. She improvised when the minister said he had to catch a flight to Ottawa from Fredericton.

“I said, ‘Can I hop in your car so we’ll have one hour to meet from Woodstock to Fredericton? And my husband will follow us.’”

Eventually, Scott agreed and they spent the next hour talking about the housing crisis and how to solve it.

She believes this conversation led to at least 40 new units for Elsipogtog during her time as chief.

Today, she continues to fight for better housing in the community of about 3,000, while promoting her Indigenous culture.

She’s a survivor, not only for herself but for those who have felt silenced.

“Don’t ever give up,” she said.

A bricklayer

Ashley Ritchie couldn’t stop her face from turning bright red when one of the men she was working with passed her a note with his name and number on it.

“I know he was the one that should’ve been embarrassed, but I was humiliated,” the 32-year-old said.

Ritchie, who was working as a carpenter in Fredericton, got the note from a roofer in another crew.

The next day, she made it clear she was married and had a job to do.

After her training as a carpenter, Ritchie learned quickly how to handle herself on a job site where most workers were men.

“If somebody has ever said anything inappropriate to me, I would literally just look at them and say, ‘I don’t know about you but I came here to work today, and that’s what I plan on doing.’”

Other women in trades aren’t so lucky, she said.

Some are whistled at, told they shouldn’t be there, are forced to hear inappropriate comments.

“You belong in a kitchen, you should be making sandwiches,” Ritchie said.

She switched from studying science to learning carpentry at the New Brunswick Community College in Woodstock in 2009. She was the only woman in her carpentry classes and didn’t know any women already working in construction.

Ritchie says the biggest challenge women face in trades in New Brunswick is getting hired. But women pay a lot more attention to detail than their male colleagues and ask important questions on a job site, she says.

“You’re just one girl by yourself, you just stand out a lot more,” said Ritchie, whose favourite machine is the bandsaw because of its ability to make fine cuts.

Carpentry was a passion she couldn’t quite let go of since enrolling in a shop class at Fundy High School in St. George.

Ritchie can remember building things as simple as a mail holder and as big as a cube-shaped TV stand, where she could hold her games and DVDs.

“We were allowed to be so creative.”

It wasn’t until 2014 that she discovered bricklaying.

“I love production and I never realized how artsy and crafty bricklaying was,” said Ritchie, who has competed in provincial and national bricklaying competitions.

“Construction is an aggressive production world. They just don’t feel like women fit into that.”

Today she works for New Boots, a network that aims to support women in non-traditional skilled trades in New Brunswick.

She said the biggest challenge women face in a skilled trade is getting hired.

“Construction is an aggressive production world,” she said. “They just don’t feel like women fit into that.”

But women balance the workplace, pay a lot more attention to detail and ask the right questions, Ritchie said.

She believes New Brunswick is behind and in desperate need of more women in skilled trades.

“When you combine a woman’s skills and a man’s skills together — and their strengths and weaknesses — you actually come out with a better team.”

A software engineer

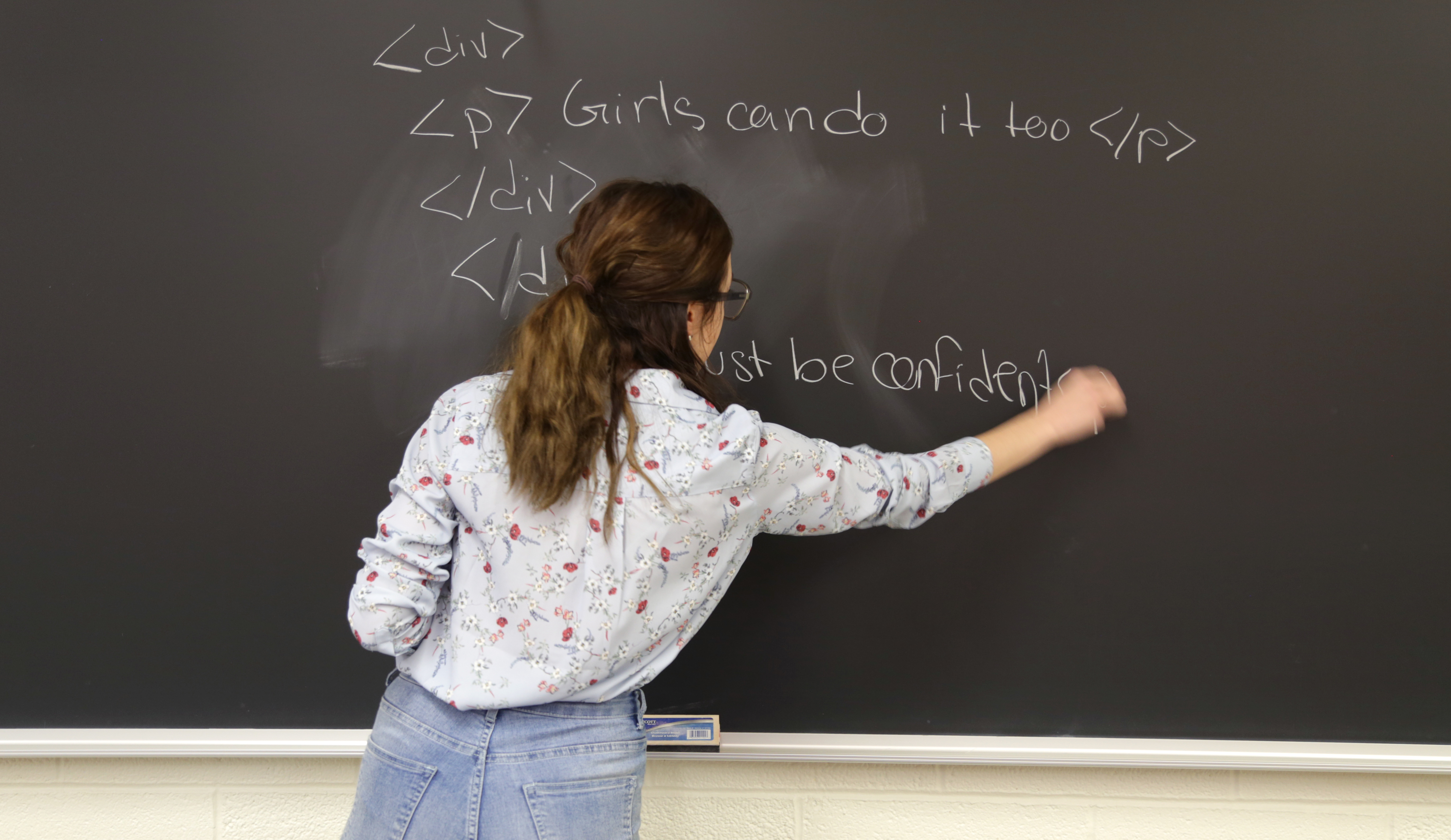

In her first-year coding class at the University of New Brunswick, Megan Doherty’s professor asked who in the room had ever programmed.

She was the only one who didn’t raise her hand in a class full of men.

“It was the worst thing ever,” said Doherty, now a fifth-year software engineering student.

Most of them had been coding since their teens and pre-teens. But Doherty, who was 19 at the time, had never looked at code in her life.

“It just seemed like all these other opportunities had already been opened for the boys and I was already two steps behind,” said the 23-year-old.

For the first two years, she felt the men in her class had an advantage.

“The difficulty is getting the parents to realize robots aren’t just for their sons.”

She spent most of her time trying to catch up.

“I had to work twice as hard to meet their level,” said Doherty, who loves playing video games and building robots.

Feeling like an outsider, the Prince Edward Island native cried whenever she returned home to Summerside over the break.

But in those first two years, it was her mother who told her to take five minutes, let it out, then get back to work.

So that’s exactly what she did.

In her third year, Doherty joined UNB Diversity Within Engineering, a group that promotes diversity and inclusion within UNB’s engineering department.

She also joined CyberLaunch Academy, a startup tech company that offers specialized programming and computer courses for kids seven to 17 years old, which she also manages.

Most kids in her classes are boys.

Over the years, she has promoted the classes at schools and science fairs and has noticed parents automatically enrol their sons but worry the program is too challenging for their daughters.

“It breaks my heart when parents put that unconscious bias in their daughter’s head from the age of seven, that automatically these opportunities aren’t geared toward them,” Doherty said.

“Growing up, a lot of women face that inequality.”

She helps the girls who do join her classes become more confident in coding. It’s a creative outlet for them and teaches problem-solving skills, she said.

“The difficulty is getting the parents to realize robots aren’t just for their sons,” she said.

“Websites aren’t just for boys. Drones aren’t just for boys, coding is not just for that seven-year-old who likes to play video games.”

When she’s not coding, Doherty loves to paint colourful flowers on empty canvases and compete in art battles around Fredericton.

Although writing an algorithm is not the same as painting a picture, she said, software engineering has allowed her a lot more artistic freedom.

Doherty particularly loves user interface, which helps websites and new technology become more user friendly.

“You have to come up with your own solutions, just like you would come up with your own artwork,” she said.

Doherty will graduate this spring with only one other woman in her program.

Then she’ll move to Toronto, where she’ll start a job at Microsoft as a technical account manager. She was headhunted by the technology company.

A fire chief

In 2017, Miscou Island was devastated by fires and a major ice storm that left thousands of people without electricity. It was also Marie-Josée Chiasson’s first year as chief of the volunteer Miscou Fire Department.

“My hands were full, holy gee, my hands were full,” she said of the January ice storm on the Acadian Peninsula.

At its peak, the storm left more than 130,000 NB Power customers without electricity.

Chiasson would get up at 5:30 a.m. and spend the day checking on residents and handing out water. She’d go to bed by 11 p.m. but would still be answering phone calls in the middle of the night.

In May, there was an overnight fire at the Miscou Island fish plant, where more than 100 people had jobs.

“Some women there, you’ll be surprised, the size of them. They might be tiny but they could pull a man of 200 pounds right out."

Then in July, a forest fire forced the evacuation of more than 20 homes. This one broke Chiasson’s heart.

“To see those people crying, not knowing what’s happening to their house,” said the native of Pigeon Hill. “It’s all the people that I know.

“It’s friends and family members. … I took it personally and let me say for a few days I didn’t have much sleep.”

But through the turmoil, there was one thing she knew for certain: she could count on her firefighters and they knew they could count on her.

“Their lives lay in your hands and you have to make sure that the firefighters come home to their families.”

In 2006, Chiasson started to train as a firefighter after witnessing a major forest fire in the area. She’s been climbing the ladder ever since.

A look back at the 2017 Miscou Island forest fire with Chief Marie-Josée Chiasson.

But it hasn’t been easy.

The first hurdle was getting into the fire department, where not everyone wanted her.

But Chiasson kept pushing and won the support of most firefighters.

“They were saying, ‘Why not have a woman? We’re all men.'”

Once on the job, she sometimes felt pushed aside in training and when calls came in.

“I fought for what I believed in and right now, today, I’m the fire chief.”

Chiasson has heard from women in other fire departments who have been told they can’t do the job because they’re women.

Chiasson encourages them to stick with it.

“Some women there, you’ll be surprised, the size of them,” she said. “They might be tiny but they could pull a man of 200 pounds right out.”