May 15, 2019

The lineups were agonizingly long for the few jobs available in 1919 Winnipeg, a city teeming with a ballooning population and choked by factory smokestacks.

Afraid of losing what jobs they could get, many workers suffered through dirty, dangerous conditions and long days.

Inflation was skyrocketing and so was unemployment as Winnipeg exploded into the third-largest city in Canada, drawing in thousands of immigrants who also made it the most ethnically diverse city in the country.

These were the conditions that set the stage for the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, an upheaval that brought few immediate gains but seeded the change that resulted in modern workers' rights.

"It was the most dramatic single event in Canadian labour history," author Donald D.C. Masters wrote in his book The Winnipeg General Strike.

The cost of living had gone up 75 per cent between 1913 and 1919. The average pay was $900 per year, yet it was estimated that $1,500 was needed to feed a family.

A large number of newcomers, hoping for a better life, instead found themselves salvaging scraps of wood and metal to slap together shacks in growing city slums.

"There were many impoverished people in Winnipeg. I think for many Canadians, it would be shocking to see those conditions," historian and strike expert Nolan Reilly said.

But something else also was taking root and beginning to flourish in Winnipeg — the union movement.

From 1900 to 1920, the number of unions in the city tripled and demands for a better life for workers steadily grew, said author Paul Moist, a former national president of the Canadian Union of Public Employees.

"Life was hard for the average working-class family in Winnipeg. The general strike gave voice to the frustration felt by many," he said.

"The solidarity of the city’s workers, and their decision to elect strike leaders to a range of public offices, would forever alter and define the geopolitical map of the city."

In Winnipeg in 1917, more days of work were lost to strikes than in the previous four years combined, Moist said.

And while there were gains for workers, they were modest — a few extra cents in pay.

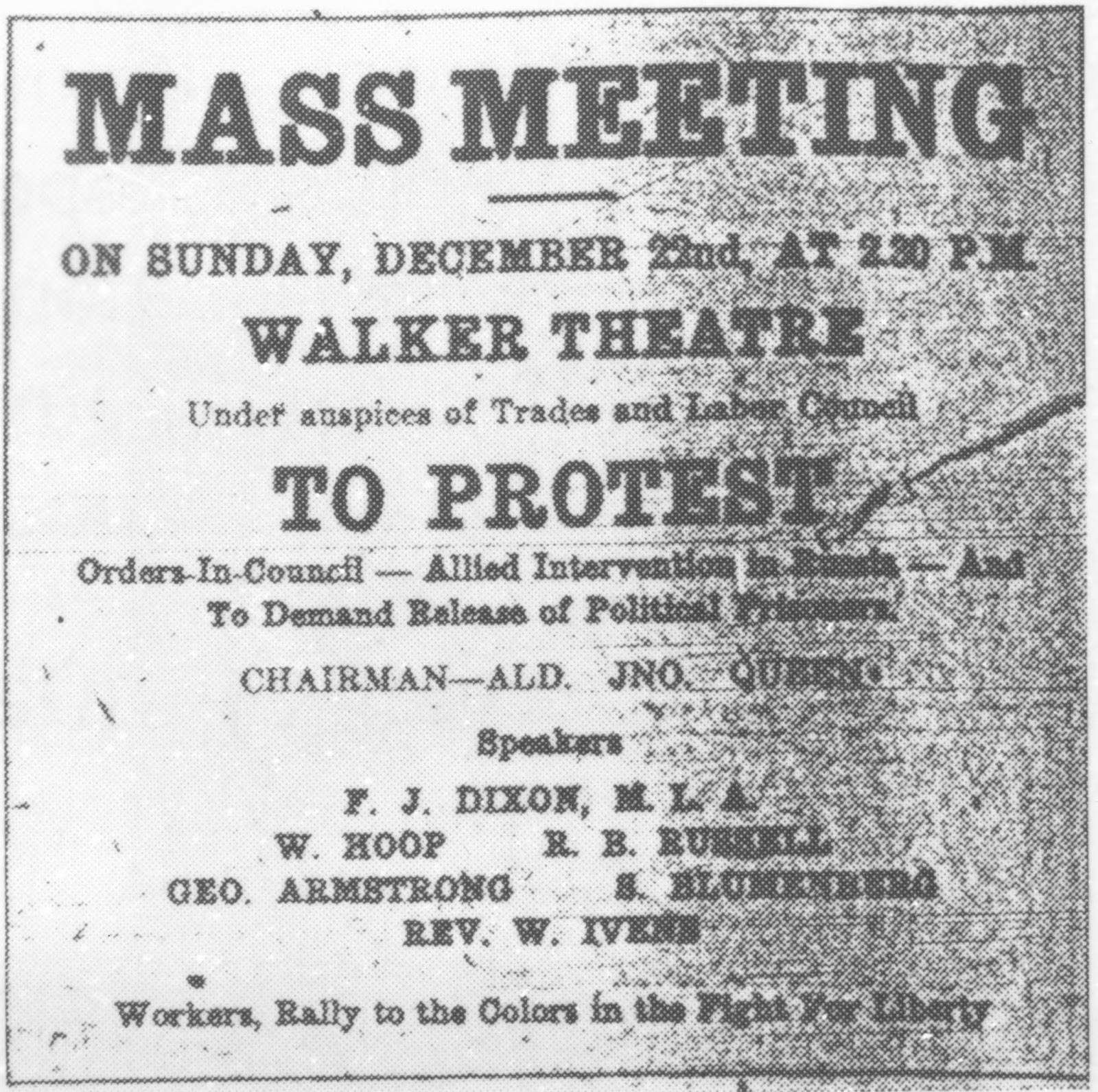

Emboldened by that success as well as a general strike in Vancouver and international events such as the Russian Revolution (also called the Bolshevik Revolution) and the German Revolution, labour leaders in Winnipeg held an assembly in December 1918.

Some 1,700 people filled Winnipeg's Walker Theatre (now Burton Cummings Theatre) for a meeting co-sponsored by the Trades and Labour Council and the Socialist Party of Canada.

Led by city councillor John Queen, the event featured speakers who went on to become prominent in the 1919 general strike, including William Ivens, Fred Dixon, George Armstrong and Robert (R.B.) Russell.

They decried capitalism, saying it no longer worked and must be abolished. They also called for the repeal of all anti-labour legislation enacted during the First World War years and the release of all political prisoners incarcerated during the war, and demanded the Canadian military withdraw its troops from the war against Russia.

A report on the meeting in the Western Labor News said Queen called for three cheers for the Russian Revolution.

The meeting ended with shouts of "Long live the working class!" and an order that, if possible, a message of congratulations be cabled to the Bolsheviks in Russia, said Dennis Lewycky, author of Magnificent Fight: The 1919 Winnipeg General Strike.

General strikes in Seattle and Brandon, Manitoba, early in 1919 buoyed the Winnipeg workers' feelings that they were on the right path.

The strike begins

On May 1, members of the Building Trades Council went out on strike after the breakdown of negotiations for better wages with the Winnipeg Builders' Exchange.

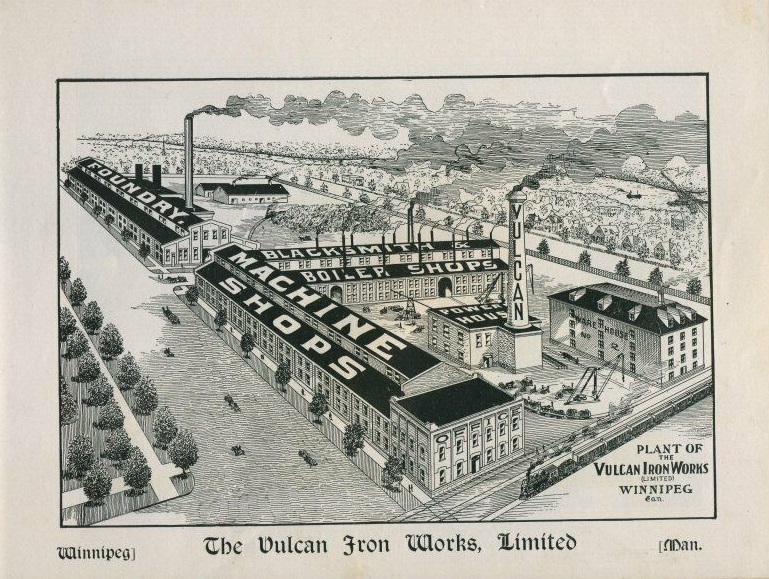

They were joined the following day by metalworkers at the city's big three foundries — Vulcan Iron Works, Dominion Bridge Works and Manitoba Bridge and Iron Works — where owners refused to deal with unions.

The metalworkers had fought for years against the so-called ironmasters for better working conditions, including higher wages and a 40-hour work week, as well as recognition of the Metal Trades Council as their bargaining agent.

Both groups appealed for support from the Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council, the umbrella organization for labour in the city.

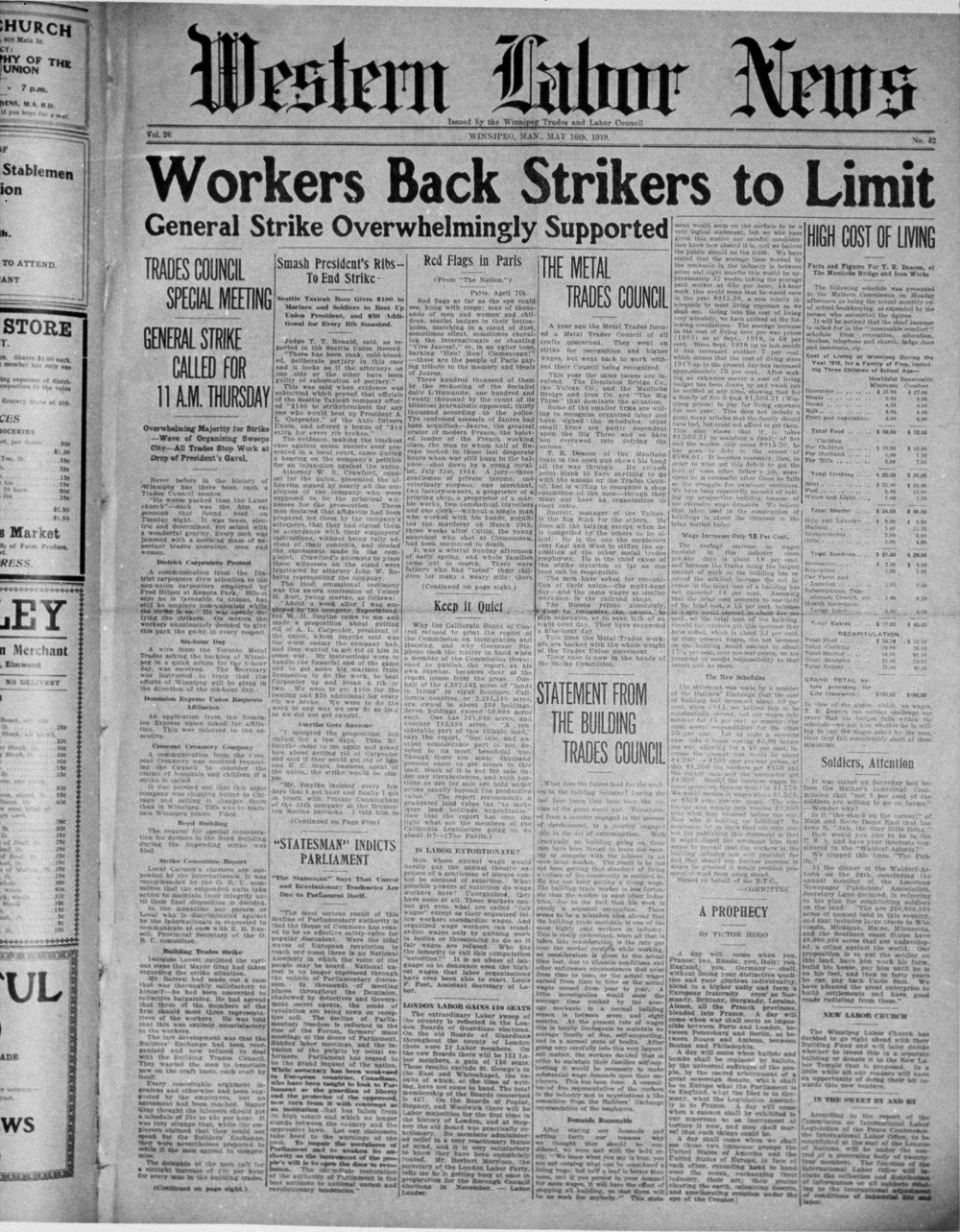

On May 6, the labour council polled its membership, from more than 70 unions, on their support for a general sympathetic strike.

The result, announced on May 13, was overwhelming — more than 11,000 votes in favour, versus some 500 opposed.

When the Winnipeg General Strike started on May 15, 1919, the first to walk out were 500 telephone operators, known as the Hello Girls, who didn't show up for their 7 a.m. shift.

By the time of the strike's official start at 11 a.m., 12,000 unionized workers had walked off their jobs. Another 12,000 non-unionized workers also abandoned their tools and trades to show support.

Although police had voted broadly in support of the strike, they agreed to stay on the job to maintain order, even arresting strikers when necessary.

In the days that followed, thousands of supporters joined the ranks. The total number of people who took part in the strike has never been confirmed, but estimates range from 25,000 to 35,000 — about one-sixth of the city's residents.

Family members of strikers often walked by their sides, boosting the strike brigade to more than half the city population of 175,000, historians Nolan and Sharon Reilly said.

Elevators shut down, streetcars stopped, home deliveries of milk and bread halted and no one delivered mail or patched through telephone calls.

Strike witness Alex Jacob discusses the impact on Winnipeg, special police attacks, and strike leaders' trials.

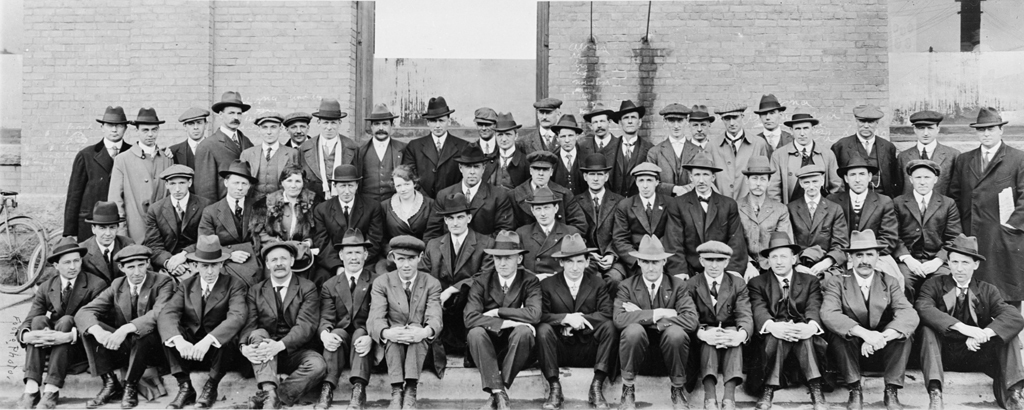

A 53-member Central Strike Committee was created to oversee the strike.

In response, employers and local government officials established the Citizens' Committee of 1,000, made up of wealthy manufacturers, lawyers, bankers, politicians and some returned soldiers.

The Citizens' Committee ignored the strikers' demands for improved wages and union recognition, concentrating instead on a campaign to discredit the labour movement as being led by foreigners trying to overthrow democracy.

The committee also found people to fill positions vacated by the strikers in an attempt to weaken the impact of the walkout.

Bolsheviks and alien enemies

When the strike started, revolutionary industrial unionism was rising in many parts of the world.

It had been less than two years since worker protests led to the Russian Revolution and the overthrow of Czar Nicholas II.

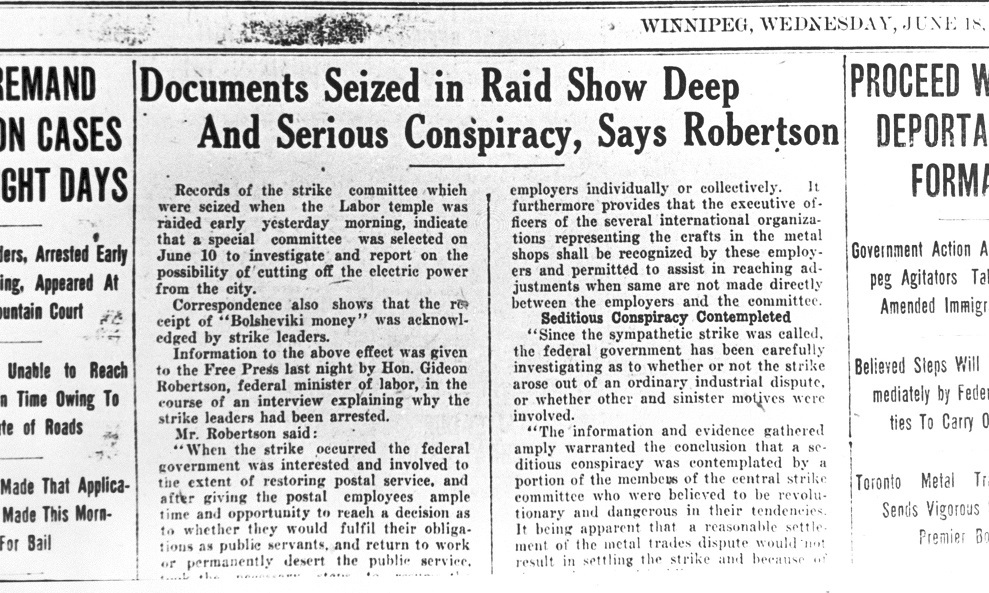

The Canadian government feared a similar revolution at home. Anti-strike factions labelled Winnipeg strikers and supporters as Bolsheviks and alien enemies, using the labour meeting the previous year at the Walker Theatre as evidence.

The city's major newspapers escalated those fears; the Citizens' Committee's newspaper, called the Citizen, labelled the strikers the "James Street Soviets," referring to the Labour Temple downtown on James.

When the strikers marched into the wealthy suburb of Crescentwood and along Wellington Crescent, residents were so alarmed that men volunteered to patrol the streets in two-hour shifts overnight.

The chauffeur of one homeowner had been an army sergeant and organized the men, giving them evening drills on the grounds of Kelvin High School, said George Siamandas, who maintains a website called Winnipeg Time Machine.

At the behest of the Citizens' Committee, Ottawa sent Senator Gideon Robertson, the labour minister, and Arthur Meighen, interior minister and acting justice minister, to Winnipeg.

The ministers met with members of the Citizens' Committee to hear their concerns but refused to meet with members of the Central Strike Committee.

Meighen issued a statement on May 24 saying he viewed the strike as "a cloak for something far deeper — an effort to 'overturn' the proper authority," author Jack J.M. Bumstead wrote in his book The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919: An Illustrated Guide.

The following day, Robertson ordered federal government employees to return to work immediately and sign an anti-union pledge or face dismissal. The province and the city ordered their employees to do the same.

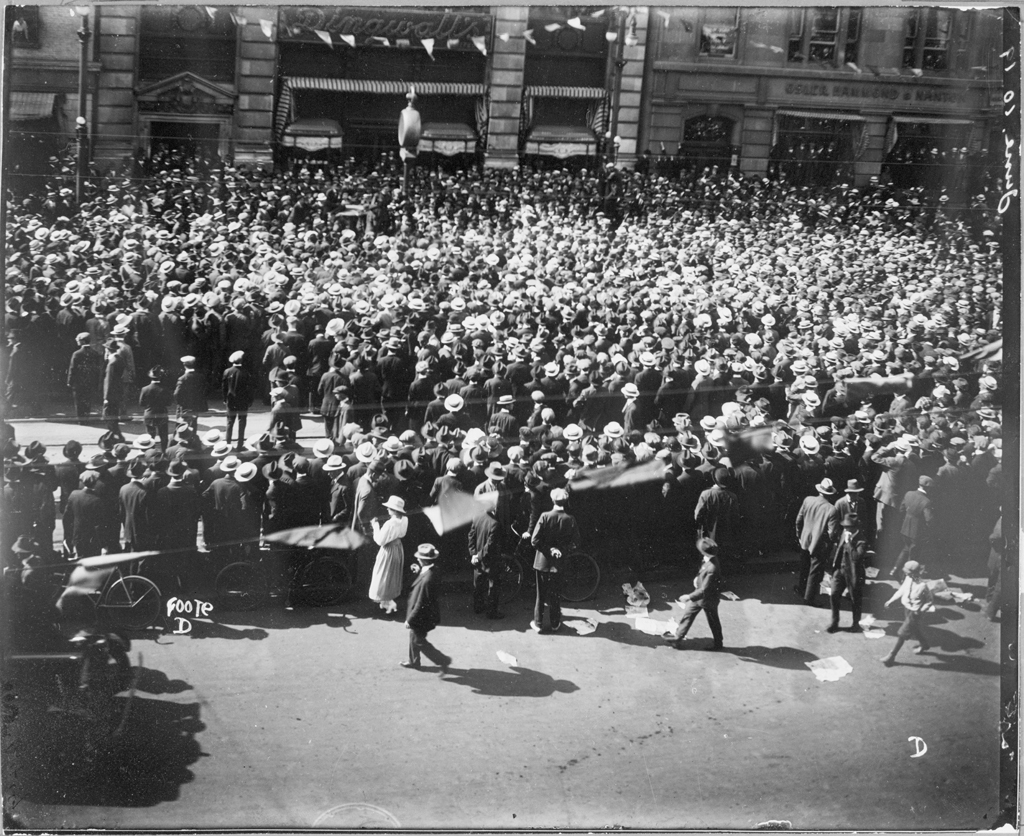

The strikers flatly rejected the ultimatums. Instead, they ramped up their gatherings in Victoria Park, two blocks from city hall, to show their solidarity.

The number of marches and parades also increased, with many orchestrated by supportive veterans rather than the strike committee. The strike leaders were more inclined to keep the peace by giving the authorities no reason to react.

"The philosophy of the strike at that time was: do nothing, commit no overt acts," said Fred Tipping, a labour organizer involved in the strike, who recalled the events during a CBC interview in 1969, four years before his death.

During an interview with the CBC for the strike's 50th anniversary, strike leader William Arthur (Bill) Pritchard recalled speaking in Victoria Park.

"There must have been 22,000 people crowded into that thing, but I was told afterwards that everyone in that park could hear every word. They were up in the trees," he said.

In the Strike Bulletin and Western Labor News, editor William Ivens printed a cautionary note on May 26, warning supporters to stay calm.

"No matter how great the provocation, do not quarrel. Do not say an angry word. Walk away from the fellow who tried to draw you [in]. Take everything to the Central Strike Committee.

"If you are hungry, go to them. We will share our last crust together. If one starves, we will all starve. We will fight on, and on, and on. We will never surrender."

The soldiers, however, were more restless. They marched.

On May 29, 1919, a delegation of 2,000 veterans visited Premier Tobias Norris and his cabinet, demanding special legislation to make collective bargaining compulsory for every employer in the province.

They said they would not back down until collective bargaining and a living wage were granted, and promised to return to hear his reply.

On May 31, about 10,000 soldiers, strikers and supporters marched to the legislative building to get that reply. Norris told them they were all matters out of his control.

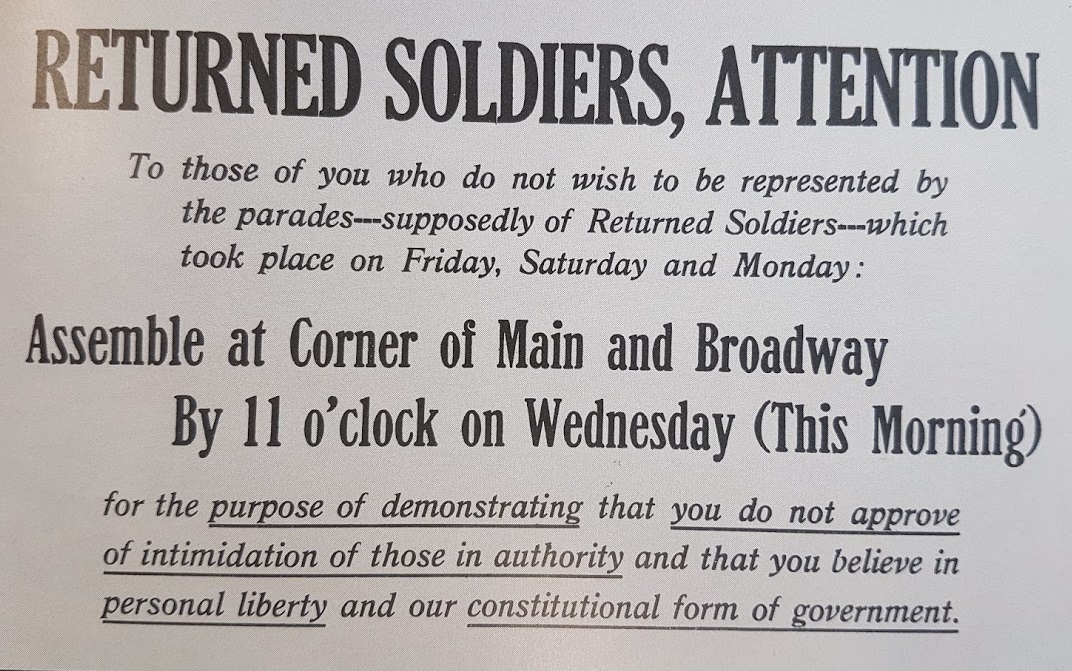

More marches were held in solidarity with the strike over the next two days, but on June 4, the anti-strike veterans held their own.

Some 2,000 men walked to the legislature to show support for the government and assure Norris they would "assist duly elected authority in re-establishment of law and order."

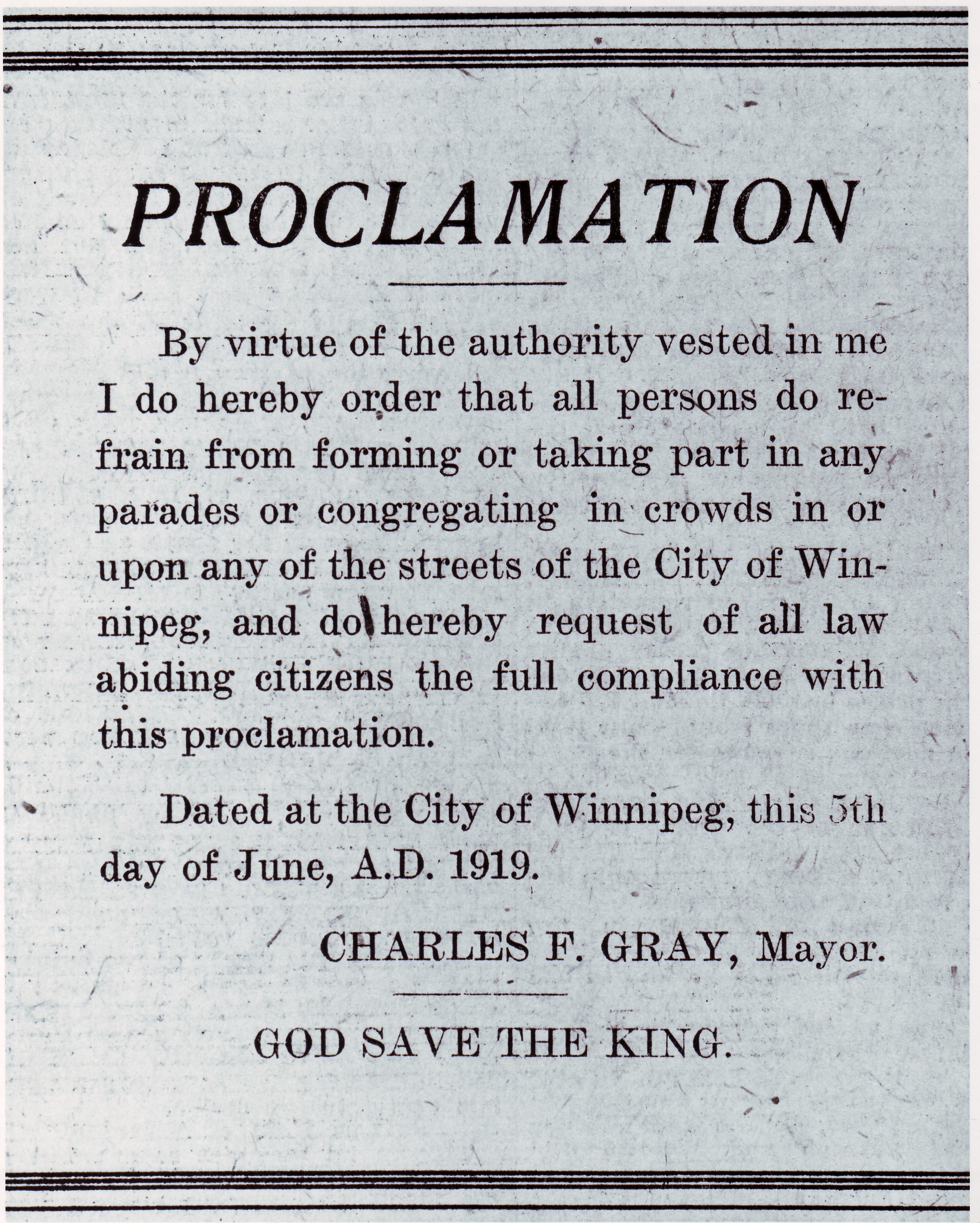

On June 5, Mayor Charles Gray banned further parades.

Federal political leaders, afraid the strike would spark confrontations in other cities, made legislative changes.

On June 6, the Criminal Code's definition of sedition was broadened, and the Immigration Act was amended so British-born immigrants could be deported, not just foreigners.

The strikers gathered, 10,000 strong, in Victoria Park the next day to hear a speech by James (J.S.) Woodsworth, a minister and social reformer.

Paralysis of services

The paralysis of services in the city led to a crisis over the distribution of bread, milk, ice and other essential goods and services.

Strike leaders, realizing a full shutdown of the city was detrimental to everyone, met at the Labour Temple and decided some services must continue.

A special food committee was established, and those given authorization to deliver necessities were provided with permission cards so strikers and their supporters would allow them to work without hassle.

Police and firefighters remained on the job, as did workers in the city's water department, who were there to ensure enough pressure was maintained to supply all structures. But without full crews, there was only enough pressure to serve the first storey of any building.

Anti-strikers said those restrictions proved the strike committee was taking control of the city.

A Winnipeg Tribune headline declared "To all practical purposes, Winnipeg is now under the Soviet system of government."

On June 9, the city fired nearly the entire municipal police force for refusing to sign a loyalty pledge, called the "Slave Pact" by critics, promising not to participate in the sympathetic strike.

In place of the fired force, the city deputized 1,800 special constables recruited by the Citizens' Committee and made up of men opposed to the strike, including some veterans.

The "specials," as they were known, were not trained officers, but they were given clubs and authority — and paid more than the fired officers had been.

The clubs were made of wagon spokes, chair legs or other wooden rods, with holes bored through one end and a rope looped through to attach to the specials' wrists.

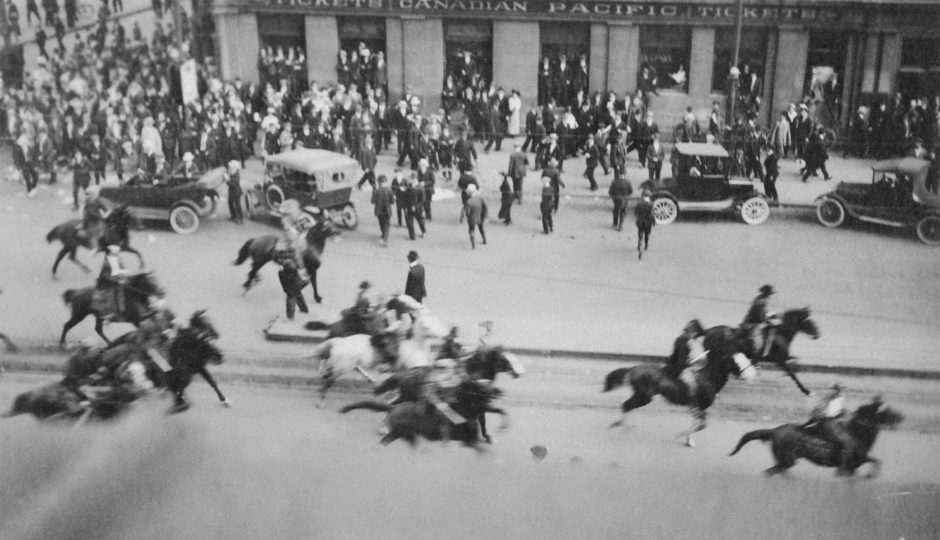

They put their powers to the test the next day when a large crowd of strikers and supporters — pro-strike veterans, men, women and children — gathered at Portage Avenue and Main Street.

Specials on foot and horseback tried to clear the crowd.

"They were working on the idea [that] two's company and three's a crowd," witness Jim Hay told the CBC on the 50th anniversary of the strike.

"If three people stopped to speak, [the specials] would come in to break the thing up. Quite close to where I was standing, there was three chaps talking and this horseman come along and says, ‘Keep going, keep going.'

"These fellas didn't move, they just kept talking. So he walked his horse in among them, three of them, and knocked one of them over backwards."

Other specials did much the same, swinging their clubs, pushing people to disperse. The crowd fought back, hurling bottles, bricks and stones.

Sgt. Fred Coppins, a returned veteran serving as a special, was pulled from his horse and beaten. He was treated at a hospital and made a full recovery, but the incident further fuelled anti-strike sentiment.

As the strike wore on, workers and their families found themselves increasingly hard-pressed to pay bills and put food on the table, but on June 16, there was some reason for optimism.

The ironmasters proposed a compromise, offering concessions to their opposition to collective bargaining. However, they continued to refuse to bargain with the Metal Trades Council.

When the proposal was rejected by the strike committee, the government swept in.

That evening and into the early hours of June 17, the North-West Mounted Police carried out a number of raids.

The raid on 1919 General Strike leader George Armstrong's home, as recalled in 1969 by neighbour Mary Jordan.

They targeted the homes of 10 strike leaders, pulling some of them from their beds. Labour halls also were raided, with police confiscating the subscription lists from the editorial office of the Western Labor News.

"I just remember it was very dark and we saw the cars and the people outside the house, there was a noise and a commotion, and we were frightened because we knew people were getting arrested and taken to jail," Mary Jordan, who lived kitty-corner to George and Helen Armstrong, recalled to the CBC during the strike's 50th anniversary.

Strike leaders Queen, Ivens, Russell, Armstrong, Abraham Albert (A. A.) Heaps, Roger Bray, Samuel Blumenberg, Michael Charitinoff, Solomon Almazoff and Oscar Schoppelrie were arrested and taken to Winnipeg's Vaughan Street jail.

Two others, Bill Pritchard and Richard James (Dick) Johns, weren't in the city at the time but were arrested soon after.

Mayor Gray said he was not behind the raids, which were primarily the idea of Citizens' Committee founding member Alfred (A.J.) Andrews and Senator Robertson, Manitoba Historical Society documents say.

On June 18, the government announced the arrested strike leaders would be held for deportation proceedings. Andrews, a former mayor and prominent city lawyer who owned a Wellington Crescent riverside mansion, would lead the prosecution.

"Just the very notion, the idea of that dual role, is an outrage," said University of Manitoba Prof. Delloyd Guth, a legal historian.

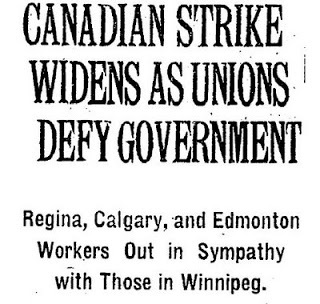

Later that morning, a meeting of angry strikers and supporters was held at Victoria Park, while sympathy strikes broke out in other parts of Canada.

Bail was granted to the six British- and Canadian-born leaders on June 20, but only on the condition that they would take no further part in the strike. The four "foreigners" — Blumenberg, Charitinoff, Almazoff and Schoppelrie — were denied bail and remained inside the penitentiary.

The freed leaders and many in the Central Strike Committee agreed to back down from strike action, fearing further arrests.

However, they could not convince the enraged strikers and pro-strike soldiers, who met that evening at Market Square, adjacent to city hall, and planned a silent march the following day.

Mayor Gray, who had renewed his ban on parades, warned them that civic authorities had "absolutely committed themselves to the breaking up of any demonstrations" and "any women taking part in a parade do so at their own risk."

That set the stage for the riotous events of Bloody Saturday, June 21.

What started as a silent parade turned into a violent confrontation, with a crowd attacking and burning a streetcar, police and specials storming into the crowd, people beaten and shot, two men dead and the military taking over the streets.

It ultimately spelled the end of the strike, which officially ended five days later.

The strikers had been defeated, but their actions laid the foundation for the unions and labour rights that protect Canadian workers today.