May 16, 2019

A sweat-drenched metalworker emerges from the dust and din of the Vulcan Iron Works factory in Winnipeg's Point Douglas neighbourhood, and the sounds and smells of nearby industry bombard his senses.

Wafting in the air is the stink of livestock from the Canadian Pacific Railway yards, within spitting distance of Vulcan's back door.

The soot and smoke that rise from coal-burning factory chimneys create a haze overhead and sting the nostrils.

And just as the shop door slams shut behind him, a steam engine locomotive whistles by with such force that it shakes the earth and pains the ear.

It's the end of a 10-hour day of hard manual labour at 50 cents an hour for one of the blue-collar labourers whose appalling work and living conditions served as the spark for the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919.

Step back in time with a 360 video of the North End:

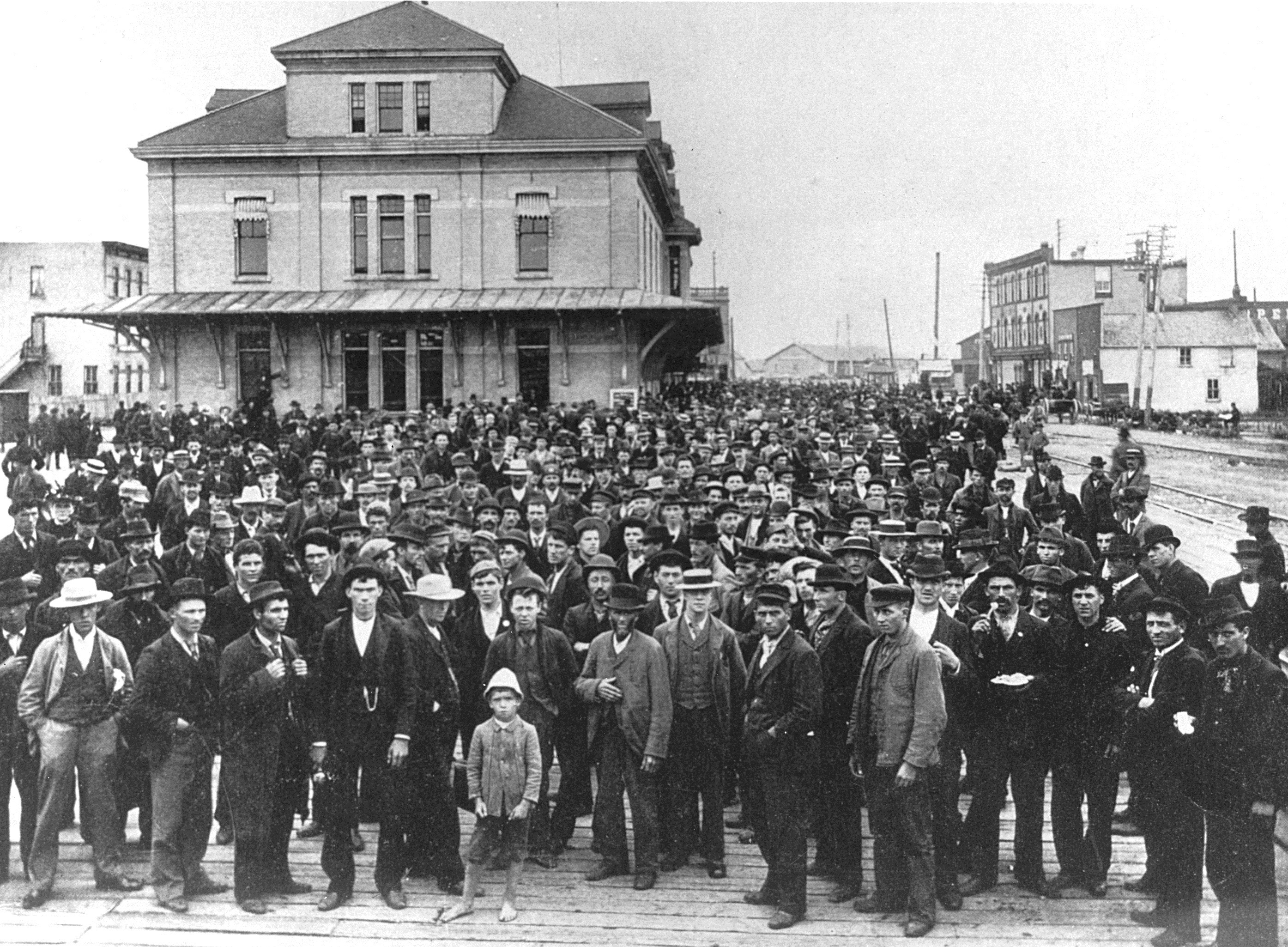

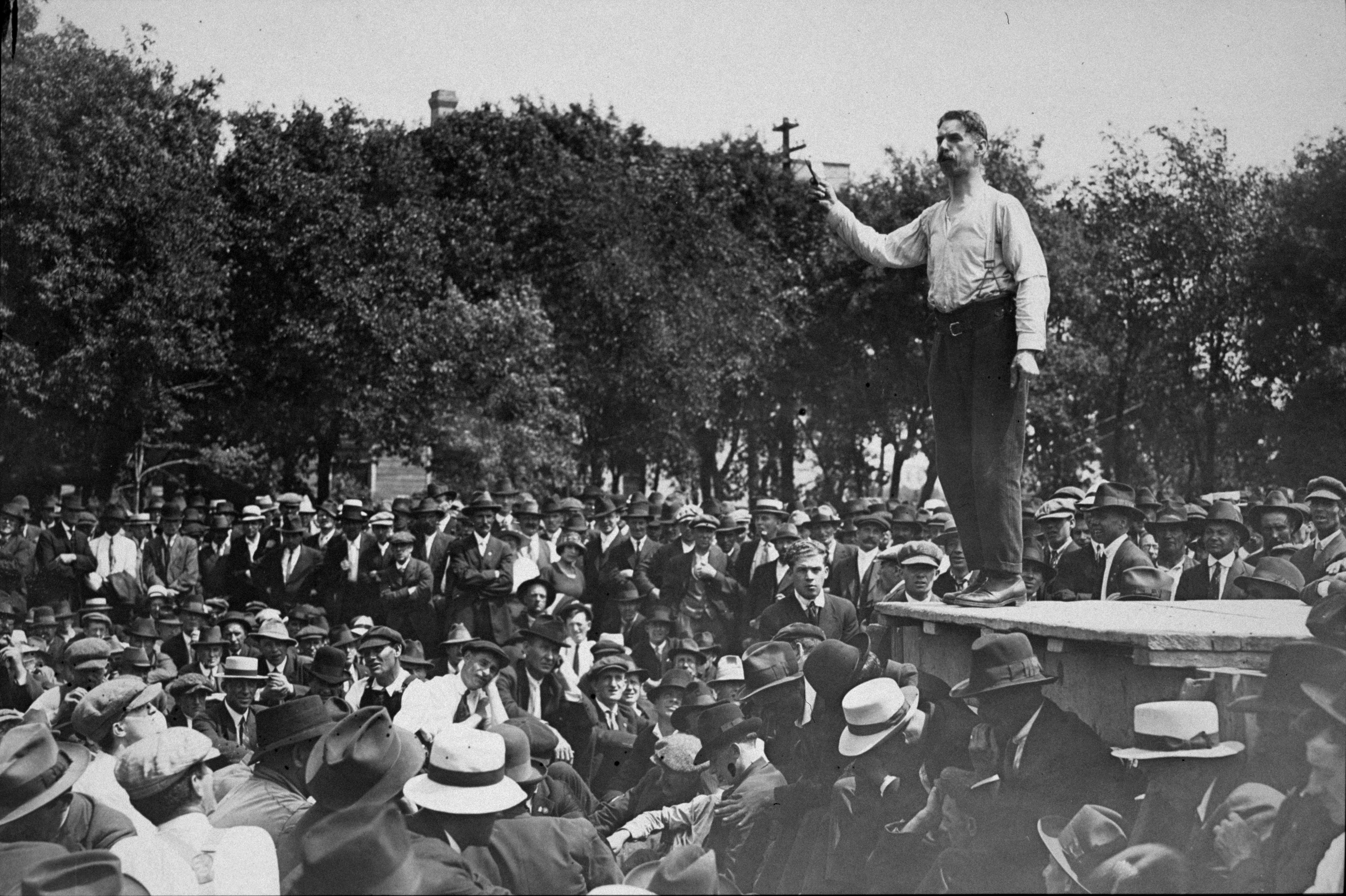

A combination of social and economic inequality and a growing awareness among the working class of these disparities led somewhere between 25,000 and 35,000 workers to walk off the job for 42 days, beginning on May 15.

The reasons so many people put their livelihoods at risk by striking in a harshly anti-union climate were manifold.

Poor work conditions, inadequate wages and the refusal by many employers to recognize and negotiate with unions culminated in the unrest that spilled into the streets and left two men dead by the end of the six-week strike.

The cost of living spiked 75 per cent between 1914 and 1918, during the First World War, and workweeks were long.

"Workers are extremely frustrated with the situations in which they find themselves," said historian Nolan Reilly, former director of the University of Winnipeg Oral History Centre, reflecting on the mood of Vulcan and other metalworkers back then.

"There was clearly a lot of wealth, because some of the elites had made a tremendous amount of money off of the war through war profiteering."

Shell-shocked soldiers looking for normalcy returned home after the First World War armistice of Nov. 11, 1918, to find conditions hadn't changed much since a depression rocked the west in 1913. Their families were still struggling to get by and, in many cases, worse off.

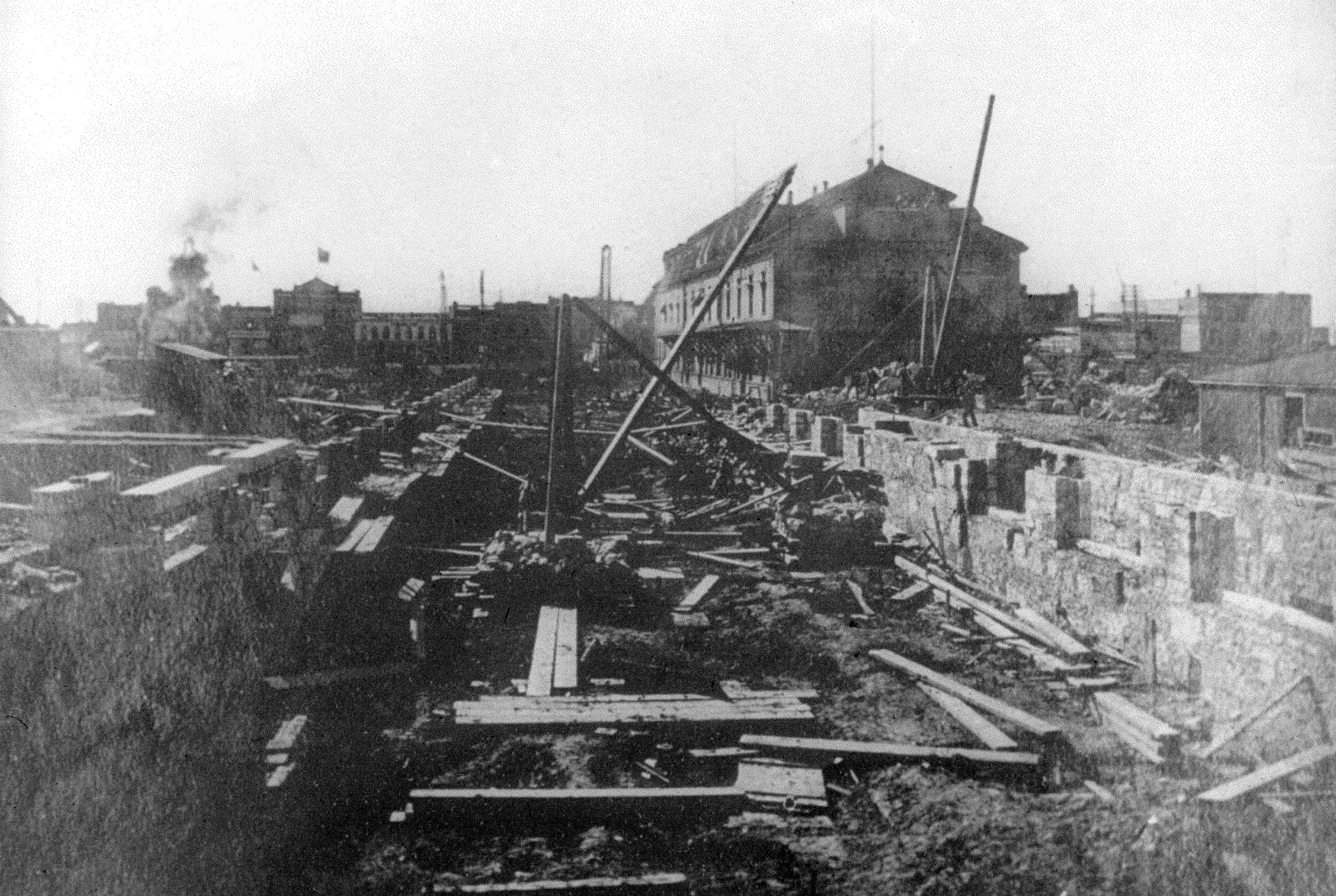

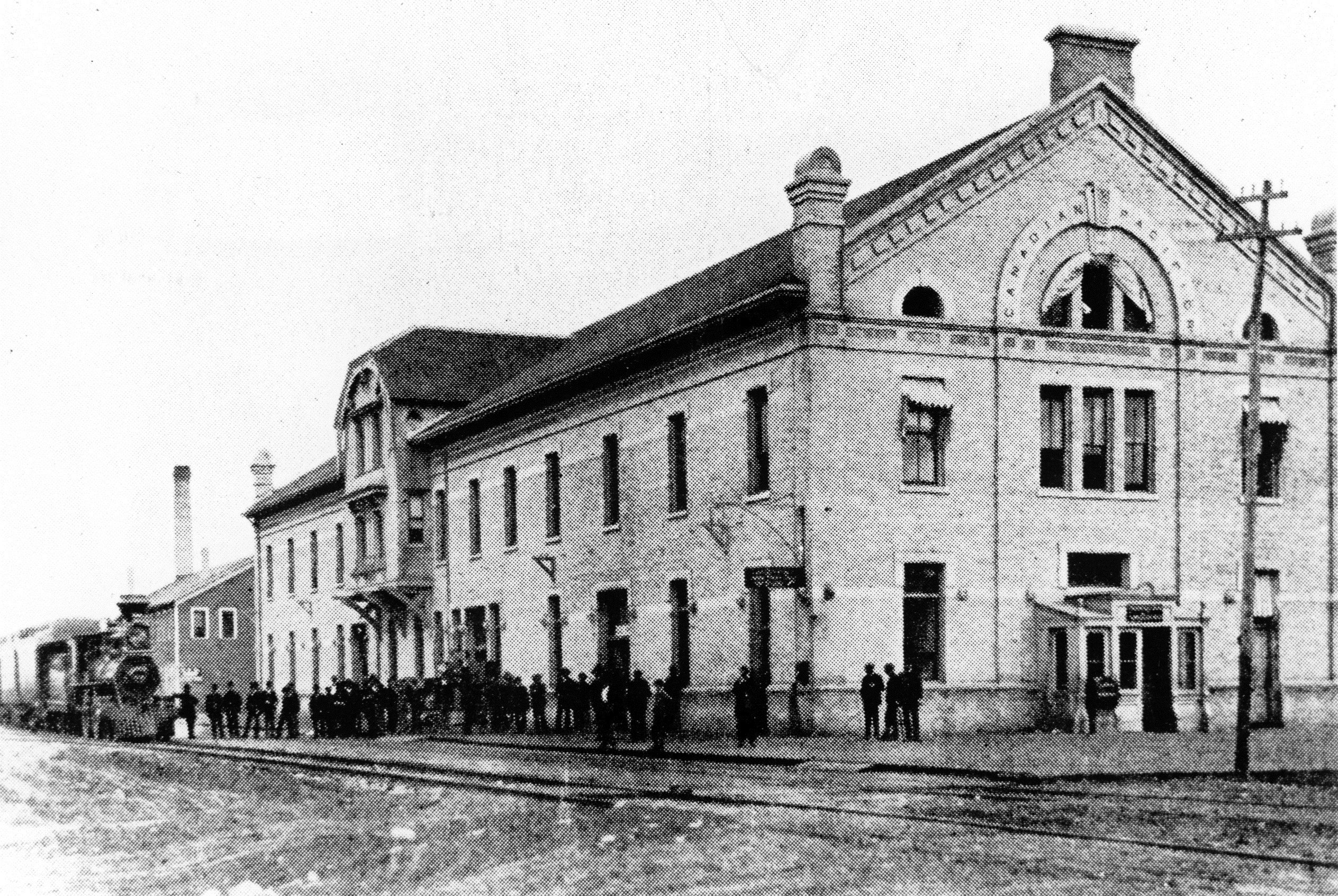

Rooted in rail

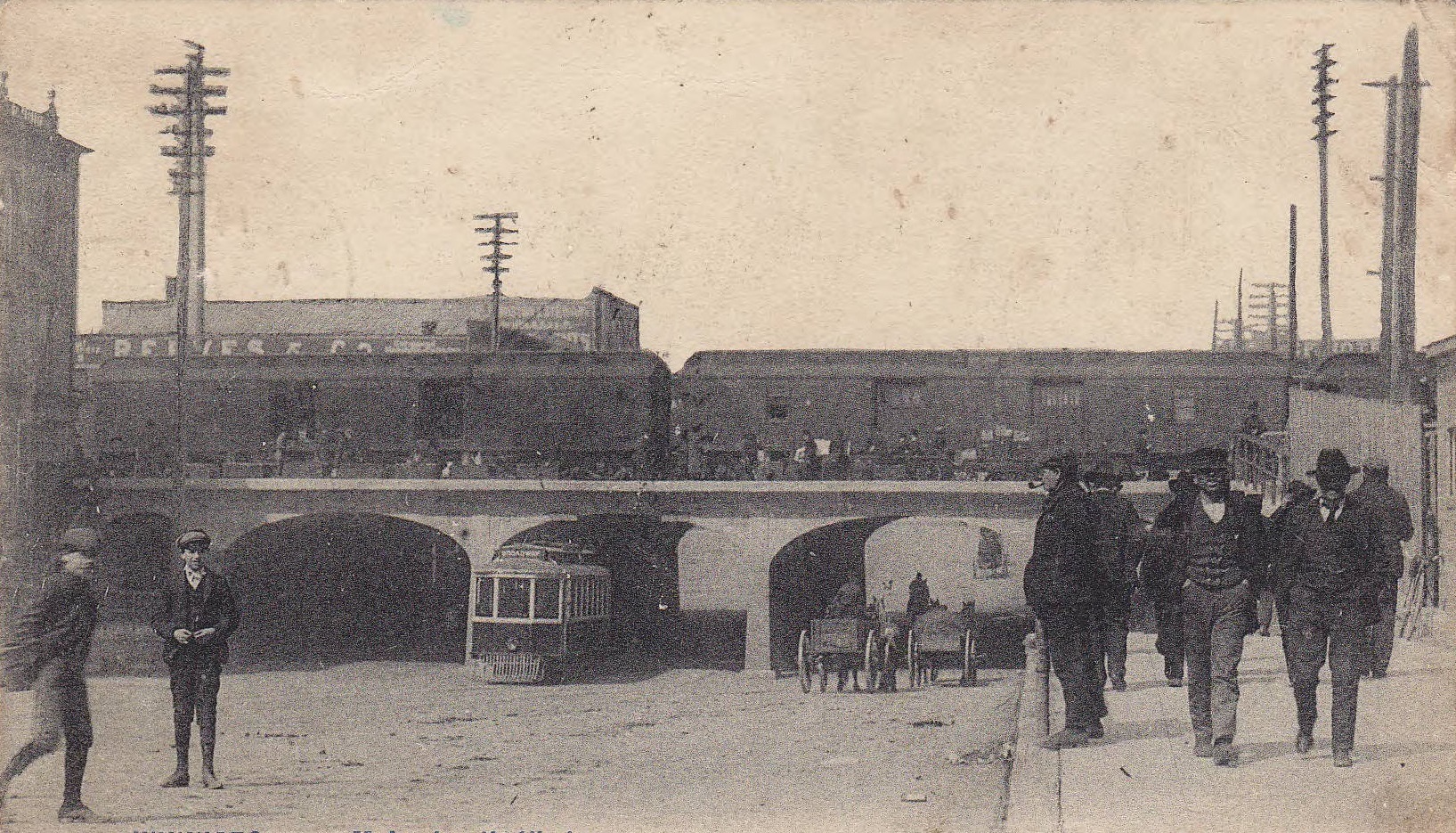

The roots of the working-class struggles of 1919 were in many ways influenced by the appearance of the Canadian Pacific Railway station in Winnipeg.

The railway transformed Winnipeg into an engine of commerce. It became a gateway to the rest of Western Canada, creating thousands of local jobs while shipping grain, agricultural equipment, goods and more west.

Dozens of businesses poured into Point Douglas to take advantage of the access to railway shipping.

There were about 80 wholesalers in Winnipeg within a decade of the CPR station opening in 1881, and that number more than tripled by century's end. By 1903, there were 103 factories in the city, mostly in the manufacturing, agriculture and household product sectors.

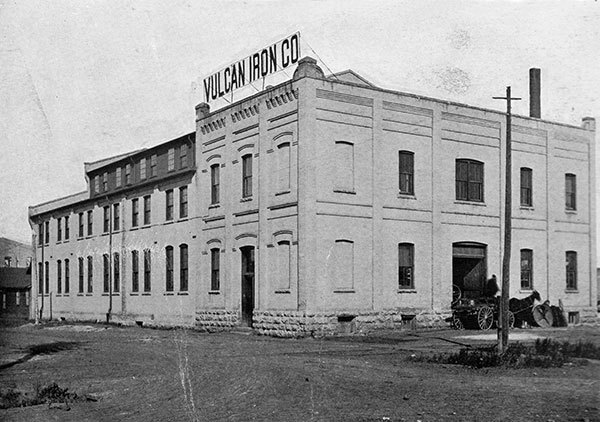

Companies like Vulcan, one of the largest metalwork companies in Western Canada at the time, took full advantage of the CP Rail shipping yard location.

Workers at the metal shop built everything from manhole covers and fire hydrants to brass building materials, rail and grain equipment and artillery for the Canadian military.

The giant Vulcan building spanned three-and-a-half city blocks, directly north of the sprawling east-west CPR lines and station on Higgins.

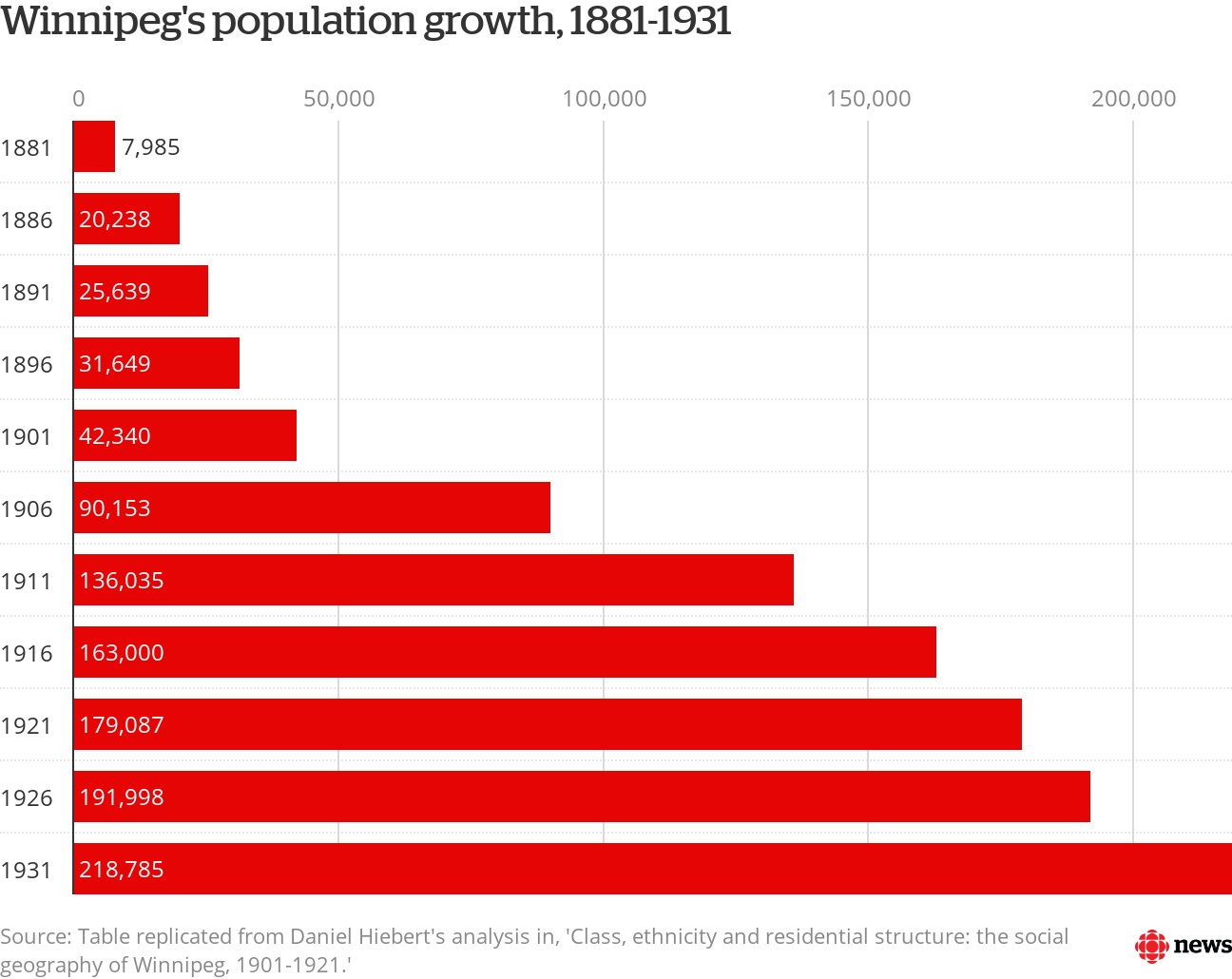

Winnipeg's population boomed: just under 8,000 people lived in the city in 1881, which swelled to 179,000 by 1921, according to census data.

The rapid growth created a demand for workers in the building, trades, construction and service sectors at the turn of the 20th century.

A large portion of Winnipeg workers were unskilled immigrants.

More than three million people, many of them from central and eastern Europe, arrived in Canada between 1896 and 1914 amid an aggressive federal government immigration campaign.

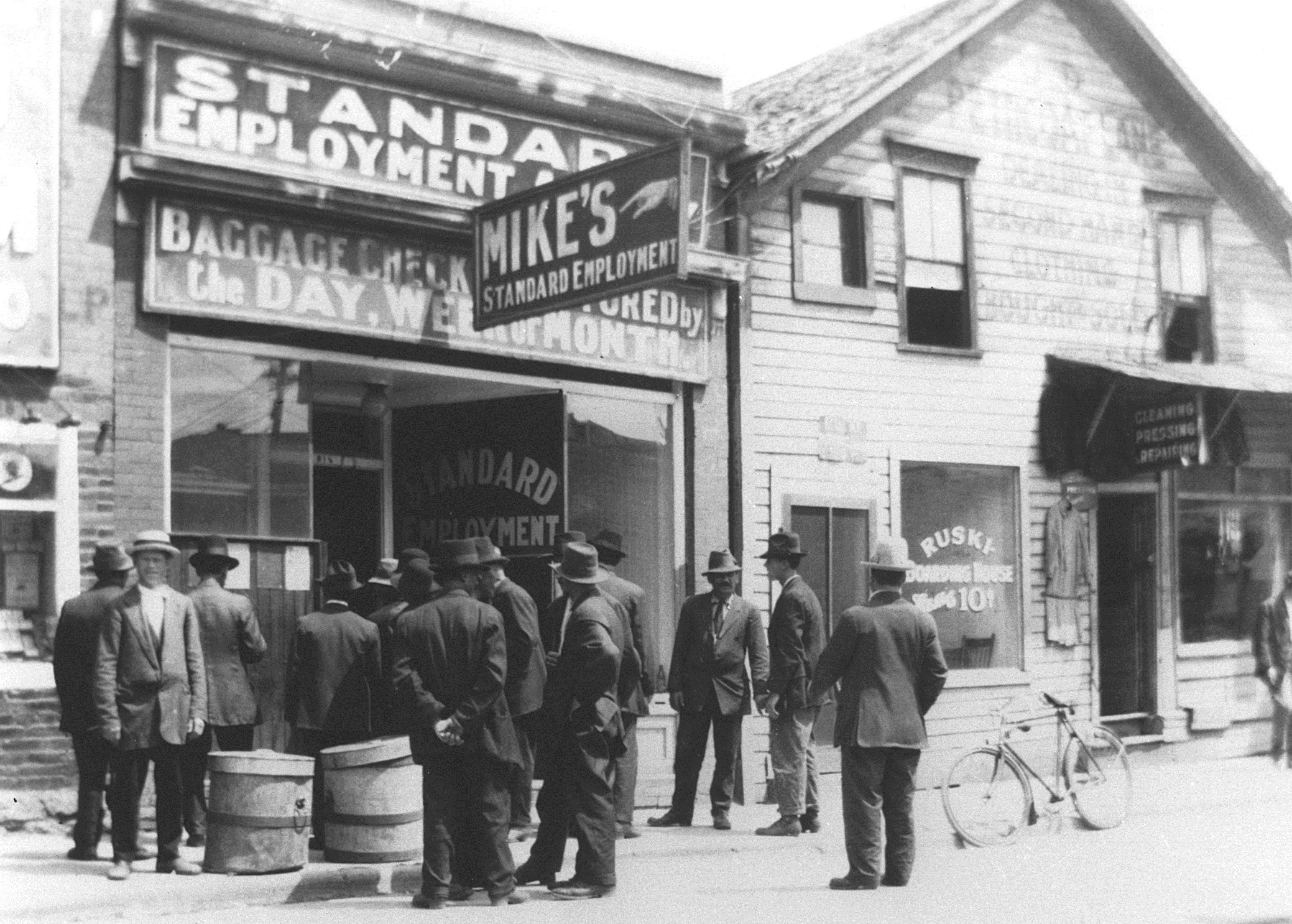

Employment offices sprouted up across Winnipeg to connect those workers with jobs. Some agencies "lived to fleece newly arrived immigrants" by charging them steep job-finding fees and locking them into contracts with measly salaries and steep room and board charges, Doug Smith wrote in his book Let us Rise: An Illustrated History of the Manitoba Labour Movement.

By 1905, more than 3,000 got on with the CPR, laying and repairing track, among other jobs, as railway expansion continued.

Hundreds more got jobs as metalworkers in machine shops such as Vulcan, which were contracted to help supply the CPR with materials.

Divided city

The east-west CP Rail line brought jobs to many and good fortune to business owners, but it also divided the city in more ways than one.

"The rail yards became a spatial and social barrier — but perhaps more importantly, a metaphor for the boundary between immigrant working-class Winnipeg and the rest of the city," said Esyllt Jones, dean of studies at St. John's College and a historian specializing in working-class health and politics at the University of Manitoba.

That boundary and all the associated business changed the atmosphere of Point Douglas.

There was an exodus of affluent families from the area in the late 1800s. Many moved south, building stately mansions in neighbourhoods such as Armstrong's Point, Fort Rouge and Crescentwood along the Assiniboine River.

Their departure, combined with the railway line and growing industry, depressed residential property values nearby and created a void that was filled by the poor working-class and immigrant families who found employment at the wealthy business owners' shops.

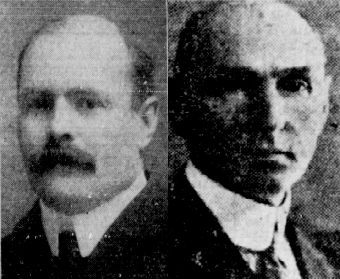

Brothers Leonard and Edward Barrett owned Vulcan; their building still stands next to the tracks on Maple Street N. in Point Douglas, with a much smaller metalwork company operating in part of the sprawling complex.

"Cities tend to grow south and west: this is a well-known real estate fact," said George Siamandas, a documentarian and historian who previously worked for Heritage Winnipeg.

"What happens north is of lesser value, is more affordable, and you end up having the kind of socio-economic division that we see in Winnipeg, in terms of who lives north of the track and who lives south of the track."

The CP Rail line meant the North End had been effectively "cut off from the remainder of the city during a crucial phase of its development," Daniel Hiebert, a University of British Columbia geography professor, wrote in his 1991 analysis of Winnipeg class and ethnic breakdowns from 1901-1921.

Crowded quarters

In the more southerly neighbourhoods roads were paved, children played in parks and many of the "beautiful mansions" had electricity and plumbing, Dennis Lewycky said.

It was another story near the train tracks.

"The social and architectural environment was so totally different," said Lewycky, author of Magnificent Fight, a new book about the strike, and former director of the Social Planning Council of Winnipeg.

"There was all the industries belching out pollution into the air, whereas in the south side of the city there was no industries," he said.

The government failed to adequately prepare for the pressure the growing immigrant population put on housing, health and education needs in the North End, Weston and Brooklands.

Green spaces and outdoor play places for kids weren't common, and a 1912 federal report on the status of neglected children admonished government to create more outdoor spaces for young ones in the North End.

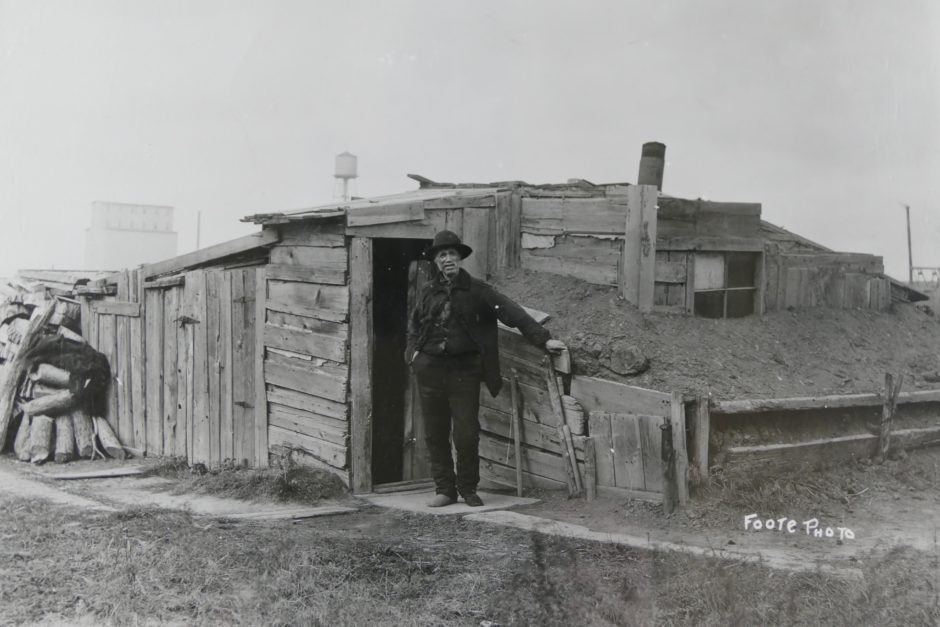

Mud roads in the area of King Street, Dufferin and Selkirk avenues were fronted by boarding houses and ramshackle dwellings that had no electricity or plumbing. Most did their business in outhouses.

Outsiders disparagingly described these neighbourhoods as the slums, foreign quarters or New Jerusalem — 80 per cent of the city's Slavic and Jewish residents lived in the area.

The residents also saw the inequality, Lewycky said.

"The workers would see how their labour was leaving them in poverty but there were all these very well-off people."

Few immigrant workers owned their crowded homes — North End property owners often squeezed two buildings into a lot designed for one. Some reports suggest as many as five families lived in single-family homes in the neighbourhood.

Immigrants forged strong connections in their communities, and for many the ghetto conditions were tempered by the fact that they were surrounded by familiar languages and loved ones.

"A lot of these people relied on their communities to get settled. The government didn't do it, the official community didn't have any resources, but it was the ethnic community that was really the integration base," Lewycky said.

'A deplorable area'

The railway yard-adjacent communities were also a public health nightmare.

Unsanitary, crowded conditions meant infections and diseases spread with impunity. There were annual outbreaks of typhoid due to the unclean water supply in the late 19th century: nearly 1,300 Winnipeggers — just over five per cent of the city's population — were diagnosed with the bacterial infection in 1904.

The Spanish flu of 1918 killed 1,200 people in Winnipeg, and the working class and immigrant neighbourhoods of the north were worst hit.

"It was a deplorable area in which to live: communicable diseases were rampant; it had one of the highest child mortality rates of anywhere in the country; up until the aqueduct [from Shoal Lake] came through, the water supply was a serious danger to the citizens," Siamandas said.

"These were the seeds of what led to the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919."

Without equal access to health care, suitable housing, fair wages and education opportunities, and with few of the creature comforts enjoyed by the upper crust, a great unrest was brewing in blue-collar Winnipeg.

No safety standards

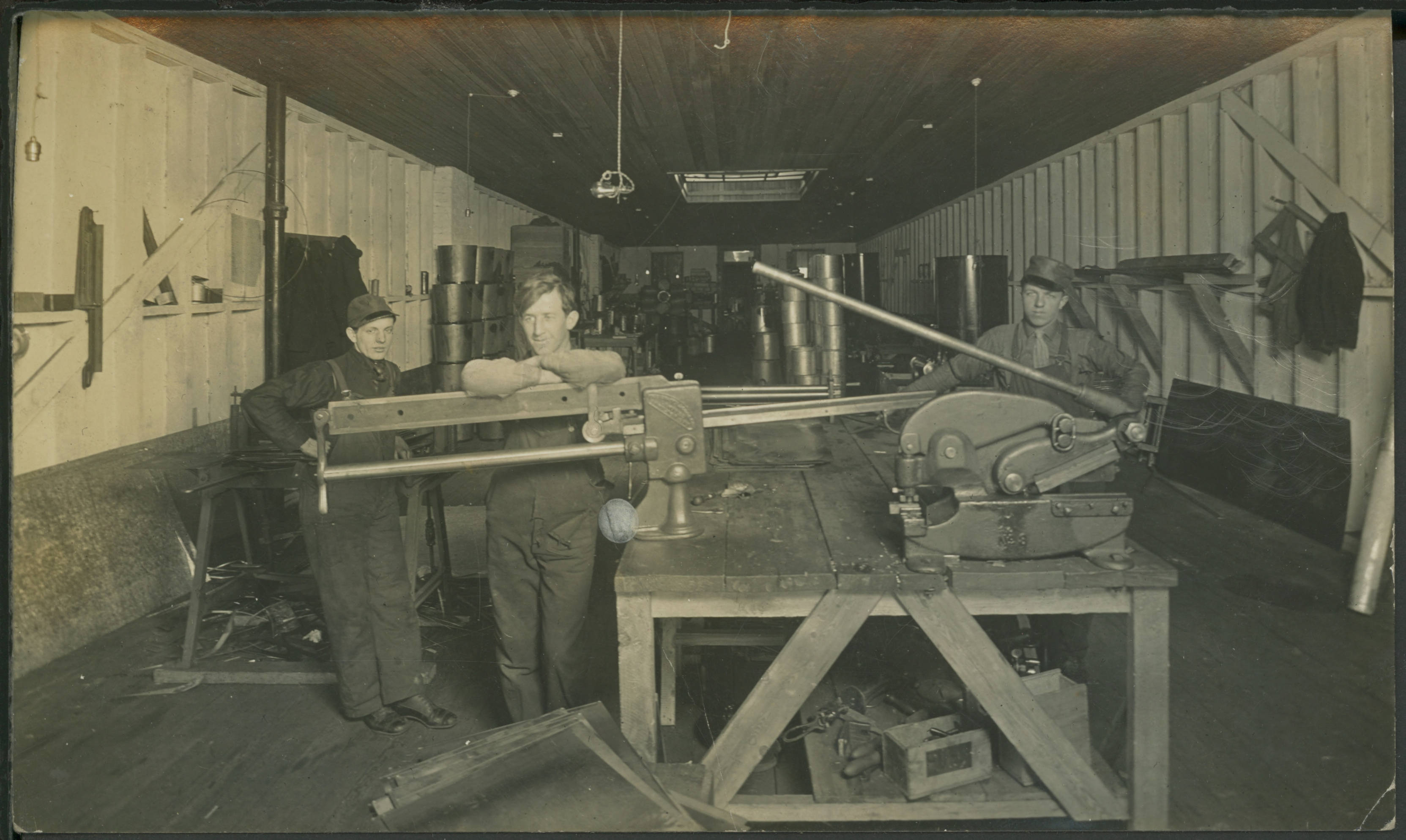

Hundreds of those blue-collar workers were employed at machine shops run by the three "ironmasters" in Winnipeg: Dominion Bridge, Manitoba Bridge and Iron Works and Vulcan Iron Works.

The still-standing Vulcan Iron Works building is a shell of its former self, but 100 years ago, Vulcan was a heavyweight and the Barrett brothers ran their business as they saw fit.

The concept of workplace health and safety standards was non-existent in the decades before the strike, Reilly said.

In poorly ventilated shops like Vulcan, metal particles filled the air.

"Workers were getting injured on the job all the time and certainly industrial illness, cancer … are simply not recognized as being problematic — and if it is a problem, it's the worker's problem," Reilly said.

The typical work week was at least six days, shifts of 10 hours or longer were the norm and wages were low.

Workers had already had enough by the early 1900s. Winnipeg streetcar drivers went on strike in 1906, and metalworkers from Vulcan, Dominion and Manitoba Bridge had threatened to strike unless they received union recognition.

Led by Vulcan, the companies essentially locked their workers out and brought in replacement staff.

'Fierce resistance'

The Barretts were staunchly anti-union and against collective bargaining. As a matter of principle, the brothers said, they would only deal directly with their workers on an individual basis.

"This is a free country and ... as far as we are concerned, the day will never come when we will have to take orders from any union," Leonard wrote in 1916, refusing to meet a committee of his employees over concerns related to wages and work conditions.

"There was fierce resistance from all employers, public and private, to unionization, and if you dared go on a picket line in Winnipeg, there were injunctions slapped on you and you were in the courts," said Paul Moist, former national president of Canada's largest union, the Canadian Union of Public Employees.

This antagonism toward unions continued as working-class tensions deepened during the war.

Wartime inflation badly eroded the spending power of the workers' low pay; hourly wages at the three metal shops ranged from 50 to 70 cents an hour in 1918.

Workers wanted wage increases of around 10 per cent and an eight-hour work day.

"[The worker] knows that what he could get for 25 or 30 cents in 1913, it costs him a dollar of those wages to get those same articles today," James Winning, president of the Trades and Labour Council, said in 1919.

Civic workers — including teamster drivers, electricians and firefighters — went on strike in 1918. About 8,000 railway and non-civic workers walked out for a period in support, Moist said, and it forced the city to negotiate new terms with those civic employees.

The "miniature general strike" worked as a device to foment change, he said, and that example resonated with many in the metal trades.

That same year some metalworkers at Vulcan and the two other metalwork shops joined the Metal Trades Council, which demanded the companies recognize it as a union representing the interests of its workers.

'God gave me this plant'

Leonard scoffed at the suggestion and declared, "God gave me this plant, and by God I'll run it the way I want to."

About 45 firms and 1,000 employees went on strike July 22, 1918, after the trades council proposed wage increases and eight-hour days for auto and metalworkers. Though a few of the shops complied, most refused to negotiate with the council, so it was back to work — but the men's dissatisfaction became a catalyst of the Winnipeg General Strike.

Workers at Vulcan and two other metal shops declared on May 1, 1919, that they would strike again for the right to unionization and a collective bargaining process. The strike started the next day.

The Metal Trades Council turned to the Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council for help. After an overwhelming vote of support from its members, the council called the general strike.

About one-sixth of Winnipeg's population — an estimated 25,000 to 35,000 people — walked off the job.

"It was massive, massive in scale," Moist said.

The city ground to a halt on May 15, 1919, as everyone from bakers and telephone operators to public transportation and postal workers refused to work.

The strike culminated in the civil unrest of June 21, Bloody Saturday, when police charged protesters who'd set a streetcar on fire and two men were killed.

Workers ended the strike four days later.

Not much good immediately came of the strike for staff at places like Vulcan. Some were fired and conditions and wages remained low in the following years.

But though it wasn't a wholesale success, U of W historian Reilly says the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike laid the foundation for labour organizing and workers' rights that have become commonplace in Canada 100 years later.

Working and living conditions as well as health care improved thanks to the strike, he said.

"No one today would want to be working in the conditions that were found in those foundries and ironworks in Winnipeg in 1919, and the reason they don't work in those kinds of conditions is because of the struggle of those people in 1919 and the unions."