March 1, 2018

Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation, which includes Mi’kmaq from all across Newfoundland, stands to become the largest First Nation band in Canada with more than 104,000 applicants for membership since 2008.

That is, if the band and the federal government can figure out who belongs.

Qalipu, which means “caribou” in Mi’kmaq, is a “new” band, having been officially established in 2011. It’s also what Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada calls a “landless band,” meaning that it does not manage any government-owned reserve lands..

Membership does come with access to Canada’s medical, educational and social programs for Indigenous Peoples, and is defined by the applicant’s status as a Indian, under Canada’s Indian Act.

Some have said Qalipu’s history could be considered a microcosm of Canada’s Nation-to-Nation dealings with First Nations peoples, with problems coming from attempts to make a bureaucratic process compatible with cultural identity. The band’s enrolment process has been widely criticized for taking too long to establish and for being founded without the inclusion and knowledge of Mi’kmaq cultural nuance.

The enrolment committee is made up of an equal number of federal government and First Nations representatives.

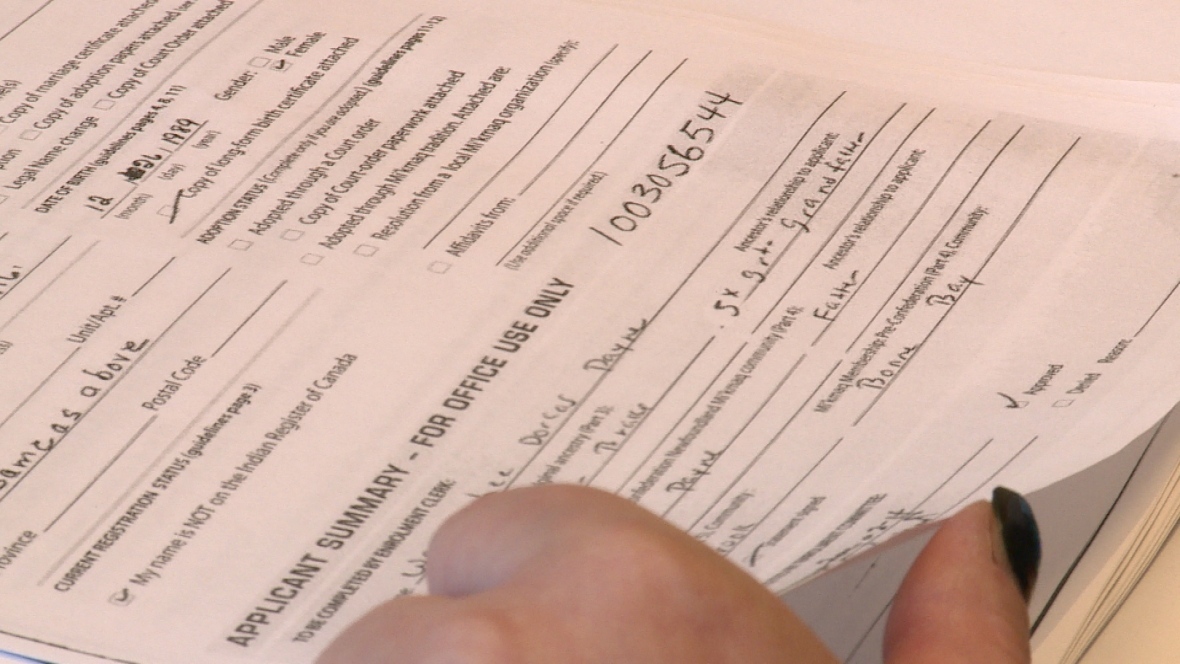

Applicants once included on a list of more than 23,000 affirmed “founding members” of Newfoundland’s Mi’kmaq have been rejected for membership in Qalipu First Nation for failing to prove their connection to their culture through tangible documentation, among other reasons.

Flat Bay No’kmaq Village Elder Calvin White said he asks himself every day “How did we get here?”

White, one of the region’s well-known elders and an original co-founder of the organization that helped to create Qalipu, was denied himself from the founding members list, but has since received membership.

Three of White’s six children were denied membership. Two of those rejected, said White, grew up and were educated in Flat Bay, but both moved away from Newfoundland for their jobs as adults. Their geographical distance from their home, says White, has nothing to do with their heritage.

“I just can’t figure out how families could be divided because of where they lived and because [their kids] pursued a opportunity to do better for themselves.”

White said hundreds of these situations have unfolded. His sister’s three grandchildren, all under the age of eight, were raised in the same home in the Flat Bay area, by the same parents. The eldest and youngest children have membership, the middle child does not.

White said he knows a family in which identical twins with Mi’kmaq ancestry, raised in Newfoundland, have different membership status.

It’s a contentious subject in Mi’kmaq communities, said White, given the history of their people in Newfoundland.

In 1949, when Newfoundland joined Confederation, Mi’kmaq communities were not recognized as First Nations under the Indian Act. The Indian status of their membership was undetermined by Canada.

After years of voicing their concern, in 1972 a group of Newfoundland Mi’kmaq formed the Federation of Newfoundland Indians (FNI). The group’s attempts to obtain status under the Indian Act were fruitless, and led to a Federal Court action in 1989, in which the FNI sought a declaration that its members were Indians within the meaning of the 1867 Constitution Act.

The legal action sparked nearly 20 years of intermittent negotiations between Canada and the FNI, filled with dissension and occasionally in-fighting from the Mi’kmaq.

In 2008, Qalipu First Nation was officially recognized with the passing of an Agreement in Principle. The agreement established an enrolment process and a committee to oversee the creation of a founding members list, based on criteria that included being “of Canadian Indian Ancestry” and being “a member [or descendant] of a pre-confederation Mi’kmaq community.”

The agreement also required that by the time the band was officially recognized, applicants to Qalipu must self-identify and be accepted by INAC as a member of the Mi’kmaq Group of Indians of Newfoundland.

At the time, it was estimated that the band would be similar to, or smaller in size to the FNI, which had about 10,000 members. But nearly 104,000 people from across the country applied to become Qalipu members. The population of Newfoundland and Labrador in the 2016 Census was 528,448.

The overwhelming spike in applications led the enrolment committee to rethink the ways in which they would determine who was Newfoundland Mi’kmaq and who was not. More time and resources were added, and the result was an addition to the FNI’s agreement with Canada.

This Supplemental Agreement was intended to give the committee “greater precision on the nature of the evidence that Applicants shall provide.”

FNI and Canada established a points system in which applicants who did not reside in within the 67 approved Mi’kmaq communities, were given scores. Membership was approved at 13 points, and was based on how much tangible evidence applicants could provide under five sections:

Frequent visits to an area of Newfoundland’s Mi’kmaq. (4 points)

Frequent communications with members of Newfoundland’s Mi’kmaq. (2 points)

Residency in Newfoundland. (3 points)

Membership in an established Mi’kmaq organization. (9 points)

Maintenance of Mi’kmaq culture and way of life. (9 points)

The fifth section, which has been the subject of much debate, requires that applicants show proof of their knowledge of Mi’kmaq culture as well as proof that they’ve participated in “cultural, religious, ceremonial and traditional activities.”

Mi’kmaw Dave Baldwin of Corner Brook failed to prove that section. Despite being described by community members as a man “that epitomizes the Indigenous way of life,” Baldwin was denied membership by one missed point.

As Baldwin lives in Corner Brook, one of the 67 affirmed Mi’kmaq communities in the province, he shouldn’t have been processed under the points system. It was put in place for those who lived away from the communities. Baldwin said his questions to INAC on the issue were never answered.

“I've been an Indian all my life," said Baldwin, 65.

"I don't need a card in my pocket to tell me who I am. I got the bloodline. All my brothers and sisters and cousins, they got their [membership], but they turned me down by one point because of culture. Never practised culture. That's so far-fetched. That was a real slap in the face to me."

Baldwin, who served as Chief of the Corner Brook Mi'kmaq Band in the 1970s, said he's experienced all aspects of his culture — the good, the bad, and the ugly.

As a teenager, he said he was called "every name in the book" for being Indigenous. At 19, Baldwin said he was badly beaten by police officer "because I was a 'g-d' Indian, they said.”

Baldwin said he was stunned by the initial rejection, so he appealed.

"I called and asked [INAC], how can I appeal this? You don't want any proof of anything?" said Baldwin.

"They told me to submit the same application. The one they denied. They told me they couldn't even look up my file. The whole thing was a joke."

As of December 2017, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada mailed more than 4,800 appeal decision letters to applicants, and there were about 8,000 decisions left to be made. Baldwin has yet to receive his.

'A mess of problems'

Brendan Mitchell, chief of Qalipu First Nation, has been at the band’s helm since 2015. He said he’s acutely aware of the concerns people like Baldwin are voicing. He calls the enrolment process “broken.”

“I don’t how they couldn’t get that extra point to get to 13, people who’ve lived in Indigenous communities all their life,” said Mitchell.

“The big problem in this whole enrolment situation really is the points system.”

Mitchell adds it’s just one of “a mess of problems,” but the points system is specifically failing what he calls “away from home” Mi’kmaq — people who have left the province to better themselves.

“[Newfoundland and Labrador] still has the highest unemployment rate of any province in Canada, so what did people do a few years ago? They moved away to go to school, or to get a job to feed their families and move them ahead.”

Mitchell said that while the supplemental agreement and points system, which were established before he became Chief, have been “damaging” to the band, he’s unable to walk away from it.

“If myself and our council today said to the government ‘we don’t want to be part of the supplemental agreement anymore,’ it wouldn’t stop it,” he said.

“It’s a binding agreement set hard in place, supported by Bill C-25. . . .The Minister [of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs] and others tell me ‘we have an agreement in place, and we’re going to see it through.’”

"The creation of Qalipu First Nation gave them the opportunity to come out and be accepted."

Mitchell said the situation often keeps him up at night. He said he’s been subjected to “personal insults, harassment and slander,” and said Qalipu’s “legitimacy” is questioned by First Nations Organizations like the Assembly of First Nations, the Atlantic Policy Congress of First Nations Chiefs and the Mi’kmaq Grand Council.

Many in the region say that Qalipu is open to applicants that could knowingly have no Mi’kmaq ancestry, but want access to resources like medical and educational funding.

Mitchell admits that the volume of applications requires a process in which applicants are “verified” as members of Newfoundland’s Mi’kmaq communities, but said he won’t “make apologies” to Canada for the number of applicants.

“Canada and the FNL said at the time that this can’t be right, and asked where have these people been for 40-50 years?

“The individual motives of these people, I’m not sure what they are. They self-identified on the paperwork . . . but I think the creation of Qalipu First Nation gave them the opportunity to come out and be accepted. If you think about it, in this area, we’re the new majority.”

'Ideological differences'

Mi’kmaw author and Elder Victor Muise said he has a hard time even thinking about the situation of his people right now.

Muise has been sharing traditional knowledge for many years, and has been an powerful, though soft spoken voice in the fight to change the process. He was added to Qalipu’s founding members list, but his brother was denied membership after applying, and appealing, under the supplemental agreement.

Muise says he still can’t figure out why, and that he’s been left frustrated and disheartened.

“The whole thing’s been a mess since the original agreement,” he said.

Muise said he believes the creation of any band under Canada’s Indian Act is destined for “straight discrimination.” He said there’s no place for Canadian politics in the Mi’kmaq communities because fundamentally, there are too many “ideological differences” between First Nations’ and Canadians’ ways of living to reconcile, especially if the Canadian government always has control.

“The people in the government have come along in a way where they need documents and numbers to justify [Indigenous] rights and life,” he said.

“It don’t work like that here. We need to meet you and grow and understand how you are, not just who you are. It’s never going to change with them.”

Muise said recently he’s been getting calls from Mi’kmaq all over Canada, people he’s known since they were children, who are wondering what to do because their status has been taken away.

One of them, a first-year university student, called crying because she wasn’t sure if she could stay in school without funding assistance. Muise said the anguish of his community has left his “soul and spirit blank.”

“I just remind them to stay calm, love one another, dance, sing and speak their language,” he said.

“Because that’s all we’ve got. We’ve got to do it ourselves, we’ve got to adapt, because the government won’t ever change.”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story said Victor Muise was denied membership in Qalipu Mi'kmaq First Nation. In fact, Victor Muise's brother was denied membership.