March 13, 2021

I. The raid

It was after midnight. Peter Schneider was asleep at home with his wife, Melissa Wiseman. That evening, they had celebrated her birthday with their kids. Dinner at Montana's. Cake. An Adam Sandler movie. Two of the kids' friends were sleeping over.

Suddenly, a loud bang erupted from downstairs. A voice rang out over a bullhorn. It was Ottawa police, commanding Schneider and Wiseman to come outside.

Wiseman went downstairs first. Schneider walked to the bedroom window and saw an armoured vehicle on his lawn and a clutch of officers in combat gear, their guns out.

"My heart was pounding through the roof. I thought to myself, like, what could I have possibly done to have a SWAT team kick my door down?" he said.

- Stream "When police don't knock" on The Fifth Estate on CBC Gem, the CBC's streaming service.

He threw on boxers and a tank top and headed down to the front stoop.

"They asked me to put my hands up, so I did. They asked me to turn around, I did."

The officers then told him to walk down the steps backwards. He did. They had him turn around again. Then they told him to get on his hands and knees and crawl across the front lawn to the curb.

"I felt like a dog or an animal. They'd clearly seen I had no weapons on me or anything. I didn't deserve that."

Someone stepped on his back, handcuffed him and put him in a cruiser, Schneider said.

WATCH: Peter Schneider re-enacts a no-knock police raid on his family:

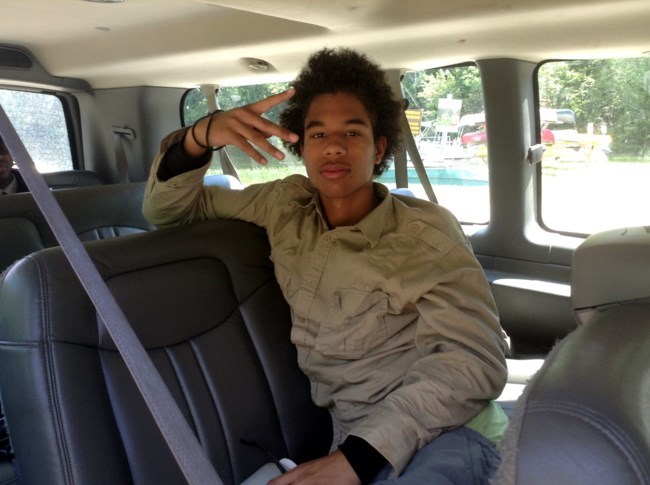

Next, officers called out Schneider's stepson, Ethan Moore, and asked him to come to the door. He was 13.

"They told me to go back inside and wake up my brothers and my friend that was staying there. I woke them all up. The guns were drawn to our head the whole entire time," Moore said. His two younger brothers were seven and nine.

"They were assault rifles and handguns, and they were standing fairly close," he said.

The kids were placed in the back of a police van. The younger ones cried, Moore remembers.

"They were very scared, asking where my parents were."

An officer took Schneider a little way down the block, then read him his rights and told him police were executing a search warrant for explosives and firearms.

"He kept asking me where the guns were, where the explosives were. I explained multiple times that I don't have any of this in the house, that they're doing this for no reason, they're wrongfully accusing me, that they're not going to find nothing," Schneider said. "He repeatedly called me a liar."

He and Wiseman were taken to a police station for a few hours while officers rooted through their home, upending milk crates and storage tubs all over the floor, leaving a maelstrom of clothing, furniture and plastic lids. Constables even removed the panel from the home's gas heater to check inside.

Officers didn't find anything. Schneider and Wiseman were never charged with anything.

That was in September 2016. The couple sued, alleging that the entire police operation negligently hung on a tip from a paid informant who had given false information to investigators in the past. The City of Ottawa settled out of court in December for an undisclosed sum.

But Schneider and Wiseman's lives have never been the same. They moved out of Ottawa, for one.

"I constantly was looking out the window for the first year or so after they did that, thinking, when are they going to come back on another tip that's not true?" Schneider said.

"I don't feel safe. I don't trust cops…. I don't get out of the house, I don't socialize with people. I stay to myself."

II. The tactic

Police in commando gear bashing their way, unannounced, into someone's home is supposed to be rare in Canada.

By longstanding legal precedent — hundreds of years old — officers are usually required to knock and state their presence and purpose when executing a search warrant.

"Except in exigent circumstances, police officers must make an announcement before forcing entry into a dwelling house," the Supreme Court of Canada summarized in a 2010 case called R v. Cornell.

The "exigent circumstances" arise when there are "reasonable grounds to be concerned about the possibility of harm to themselves or occupants, or about the destruction of evidence," the court said. But an investigation by CBC's The Fifth Estate has found that in some parts of the country, for certain kinds of cases, no-knock raids have become the norm.

WATCH: What happens when Calgary tactical officers execute a search warrant and their battering ram doesn’t work:

In drug cases investigated by the Ontario Provincial Police, for instance, a detective testified in 2018 that "probably 90 per cent of the warrants I've been involved with have been forced entries."

The veteran officer said for search warrants involving narcotics in pill form, it's close to 100 per cent. The only drug cases that don't almost certainly trigger a door-bashing, guns-drawn raid are cannabis grow-op busts, he said.

The rationale, police say, is that powdered drugs like cocaine or pills like fentanyl can be quickly flushed down a toilet, while cannabis plants can't.

"If we were knocking on drug trafficking doors, I’m going to suggest that we would never seize cocaine," the OPP detective testified in 2018.

No-knock police raids can take several forms. A less intrusive tactic is called "breach and call-out" — what Ottawa police did at Schneider's home in 2016 — where constables batter down the door but don't enter right away, instead calling the occupants to come out with their hands up.

The most full-throttled approach is known in law enforcement circles as a "dynamic entry": Rifle-wielding police, usually in combat gear, breach a door with a battering ram, sometimes setting off a flashbang or stun grenade just inside the threshold and then stream into a home.

WATCH: Kamloops RCMP ring the doorbell before bashing in the door:

It's this tactic that an Ottawa judge ruled last year has become endemic within the city's police, "the rule rather than the exception." The consequences have ranged from violations of constitutional rights to the death of a young man in October after a tactical team forced its way into his highrise home in search of guns and drugs.

"However long the practice has been in place, it reflects a casual disregard for charter rights," Ontario Superior Court Justice Sally Gomery wrote. Section 8 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms protects everyone against "unreasonable search or seizure" by police.

"The police cannot operate from an assumption that they should break in the door of any residence that they have a warrant to search," Gomery wrote.

One problem is, nobody knows for certain how often Canadian police commit these forced entries. Once detectives get their search warrant approved by a justice, it's up to officer discretion whether the "reasonable grounds" exist to smash in a door. They don't need a judge's prior approval, so there's no easy paper trail.

The Fifth Estate sent access to information requests in December to Canada's eight largest police forces, asking how many of the full-bore dynamic entries they did in the last two years while executing search warrants. As of Friday, only three had replied.

The RCMP said its tactical teams deployed 99 times in 2019 and the first half of 2020 for high-risk warrants, but it couldn't say how many of those are dynamic entries based on search warrants. Quebec's provincial force, the Sûreté du Québec, reported 143 such entries in 2020 and 156 in 2019. On the other end of the scale, and the country, a Vancouver Police Department spokesperson said the force did none.

Calgary police said they would have to go through reports of every search warrant by hand to figure out which had been executed dynamically. The Toronto Police Service didn't reply, but in 2012, one of its tactical officers testified that his team does almost 200 dynamic entries a year.

The lack of data means there's limited police accountability because there's no way to know how often guns or easily disposable drugs actually were found, Toronto-based criminal lawyer Erin Dann said.

"I think it's often seen as justified later because the only ones that ever get to court are where the police go in and actually find what they're looking for," said Dann, who fought a recent case at the Ontario Court of Appeal over dynamic entries.

"So you have this kind of skewed idea where 'Look, every time we do it, we find drugs.' But we have no sense of how often these types of warrants get executed and then no charges are laid or no drugs are found.

"Even civil cases would be rare because as long as the warrant was valid, it would be hard to win a lawsuit," Dann said.

Another glaring problem with the lack of data is it obscures how no-knock warrants might weigh on communities differently.

In the United States, a 2014 study by the American Civil Liberties Union looked at more than 800 SWAT team deployments, most of which were for executing search warrants. The authors found that Black Americans were more than twice as likely to be subjected to a SWAT team search warrant raid than white residents.

There is no easily available comparable data for Canada, which Carolyn Greene, a professor of criminal justice at Athabasca University, says needs to change. Her research on residents' experiences of policing in Toronto's Regent Park and St. James Town — two neighbourhoods in the city's downtown where more than two-thirds of residents identify as people of colour — suggests there are deep inequalities.

"Over two-thirds of our participants indicated that they'd had some experience with police search warrant executions. Not all of them involved SWAT being deployed…. However, having police come to your door and demanding entry is scary."

III. The tragedies

Anthony Aust had troubles with the law, including convictions for drug offences and obstruction of a peace officer. Early last year, he was arrested again, on drug and gun charges, and put under house arrest with a GPS ankle bracelet while awaiting trial. His family believes he then became depressed and say he was deeply afraid of police and of going back to jail.

On Oct. 7, just before 9 a.m., police smashed their way into the Ottawa highrise where 23-year-old Aust was living with his mother, stepfather, 94-year-old grandmother and two younger siblings. Investigators had a warrant to search for more guns and drugs.

WATCH: Ottawa police storm into a 12th-floor apartment:

After forcing open the door with a battering ram, tactical officers in grey combat uniforms yelled "Police! Don't move!" Home surveillance video shows them setting off a flashbang grenade just inside the entrance and smoke filling the hall, as officers file in. Aust's stepfather, Ben Poirier, said he was forced to the floor and handcuffed behind his back.

Exactly what happened next is under investigation by Ontario's police watchdog. But this much is certain: Aust fell from a bedroom window, plunging 12 storeys to his death.

Police found heroin and fentanyl, but they didn't find any guns.

Ten years earlier, a Black man also in his 20s died after a police no-knock drug raid in a Toronto highrise. In that case, an officer shot Eric Osawe and was charged with murder, but three levels of court concurred that it was an accident.

In 2016, tactical officers in London, Ont., shot dead 35-year-old Sam Maloney at his family home in front of his wife and kids while dynamically executing a search warrant for computer tampering charges.

Maloney was known to distrust authorities and shot the first officer he saw entering his house with a crossbow before running down a hallway holding a hatchet overhead.

A report by Ontario's Special Investigations Unit, the provincial police watchdog, found police were justified in killing him, but questioned their use of a search warrant in the first place, calling it "obviously deficient" and an apparent "ruse" to arrest Maloney.

The same year, 46-year-old Bony Jean-Pierre died after being shot in the head by a Montreal police officer's rubber bullet during a dynamic entry drug raid. The officer was acquitted last month of manslaughter.

Law enforcement officers have died, too, during no-knock raids. Sgt. Daniel Tessier was on a team of police from Laval, Que., carrying out an early morning dynamic entry on the home of a bar owner in March 2007. Officers were looking for evidence of wholesale cocaine trafficking. What they encountered was a startled Basil Parasiris, jolted awake by the noise and afraid he and his family were facing a home invasion.

Parasiris grabbed a nearby, loaded .357 magnum, and when Tessier popped into the bedroom — in plainclothes, with the word "police" on his vest covered by a flap, a jury later heard — Parasiris fired three times. He was acquitted the following year of first-degree murder, having persuaded jurors he acted in self-defence.

Twenty years before Tessier's death, a Vancouver police officer, Larry Young, was shot dead during a dynamic-entry raid on a cocaine dealer. It's the last time a Vancouver police officer died on the job.

But perhaps no fatality has challenged the use of search warrant tactics over the last year as much as the death of Breonna Taylor, an emergency room technician, in Louisville, Ky., last March.

A police violent-crime squad was investigating Taylor's ex-boyfriend and obtained warrants to search his home, but also hers, believing he used it to stash drugs.

In the early hours of March 13, they busted down the door of her apartment while she was falling asleep in bed with her new boyfriend, Kenneth Walker. Scared by the noise, Taylor and Walker called out, but never heard any officers identify themselves, Walker said.

Fearing a break-in attempt, Walker grabbed his licensed handgun and fired one shot — aiming low, he said. The bullet struck a constable in the leg. Police fired back, riddling the apartment, and one next door, with bullets. Six of them struck Taylor, killing her.

There were no drugs. Charges initially filed against Walker were dropped. Three of the police officers were fired and one faces criminal charges.

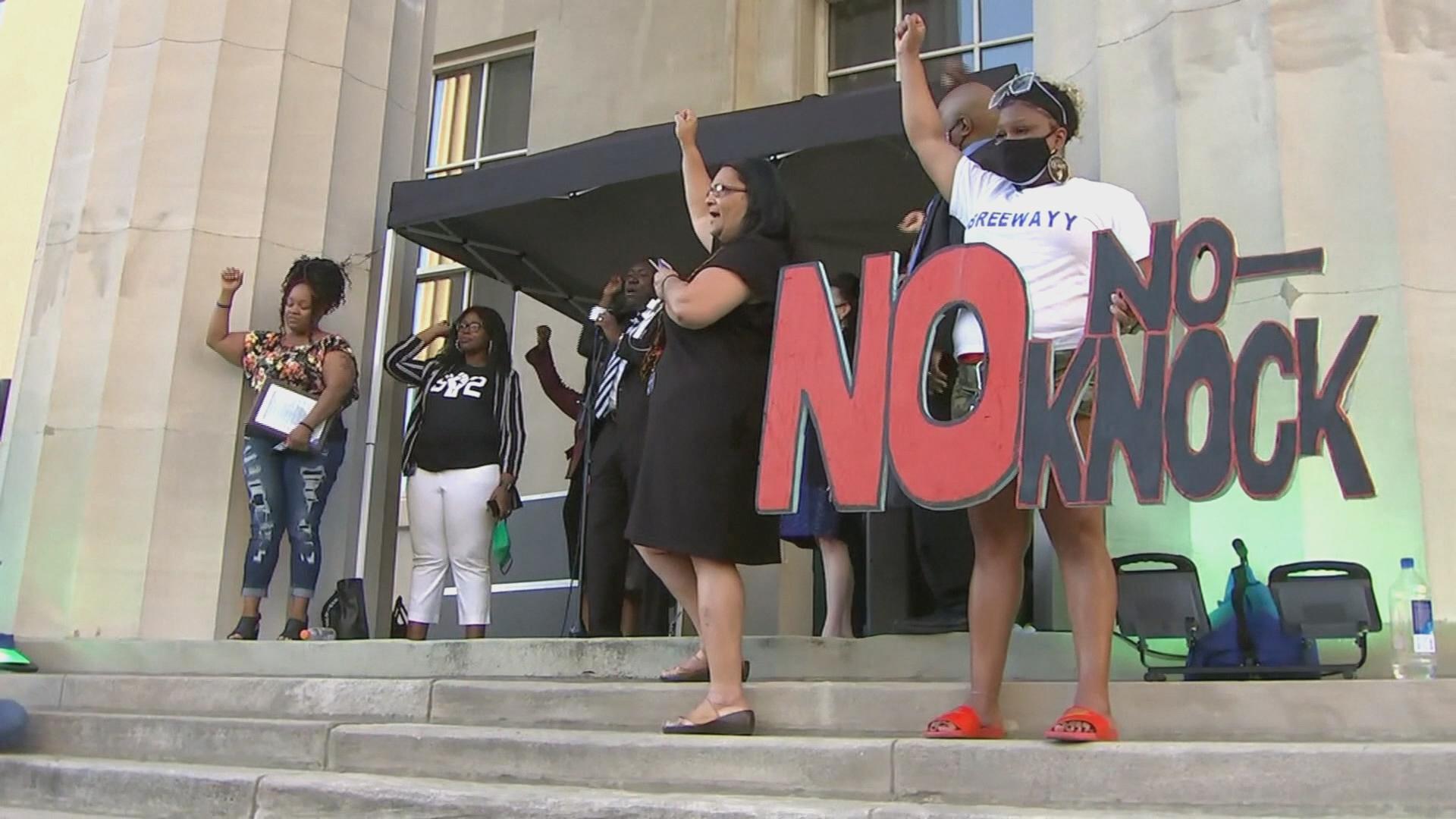

IV. The bans

All these cases underscore a probing question: Are guns-drawn, no-knock, dynamic entry raids really safer?

Taylor's killing by Louisville police brought that question into tragic relief. Many U.S. communities now think they have an answer.

The City of Louisville moved to ban the use of no-knock warrants by its police in June. Other municipalities and states have done likewise. A bill to ban no-knock warrants in all federal drug probes passed the U.S. House of Representatives last week and heads now to the Senate.

Even before the bans, in three dozen American states, unlike in Canada, police needed prior approval from a magistrate to execute a search warrant by bashing down doors.

'No one's gotta die. They don't have to die. Like, $14,000 isn't worth it, any amount of dope's not worth it either.'

Chris Carmona, a consulting instructor with the U.S. National Tactical Officers Association, said that in his experience as a SWAT team member in California, that requirement already helped make no-knock raids rare there. "Ninety-nine-point-nine per cent of the time, it's not going to happen." Both judges and police in the state just don't see the merits.

There are a number of serious safety risks to no-knock raids, Carmona said. Innocent residents might think it's burglars and reach for a gun, like 92-year-old Kathryn Johnston of Atlanta did in 2006. Plainclothes police shot her dead. In drug cases, dealers are often getting ripped off, "so they might think it's robbers coming after their stash" and defend themselves violently.

He said there are often better ways. Plainclothes officers can wait outside until a suspect leaves to buy groceries or go to work, arrest them quickly in the street and only then search their home. A co-operating family member can be enlisted to help make it happen.

Sometimes police will even use ruses, like faking a car accident out front on the street to get someone to leave their house so officers can arrest them before executing a search warrant, Carmona said.

In search warrants for guns, which can't easily be flushed down a toilet, police can surround a home and call out to the residents using a bullhorn, demanding they exit and surrender. It might take a lot of waiting, Carmona said, but it can save lives.

"If it takes two days, it takes two days," he said. "If you know there's a likelihood of a potentially violent encounter, it's always better to err on the side of caution and go another route."

Even on the Louisville police force that shot and killed Taylor, there is open criticism of what happened. The SWAT team wasn't involved — in fact, it hadn't even been told of the operation. In the aftermath, the squad's commander was blunt.

WATCH: Body camera footage and analysis of what went wrong in raid on Breonna Taylor’s home:

"As we debriefed and kind of looked over, it was just an egregious act," Lt. Dale Massey told investigators with the department's internal affairs unit in interview footage and audio released to the public last fall.

"Our priorities are people.… We're not going to rush in to get dope. Human life's more important than any amount of dope, right? So, with the times, our tactics have changed as well."

In Canada, some parts of the country have already dialed back on how they execute search warrants.

Tom Stamatakis is president of the Canadian Police Association, which advocates on behalf of more than 60,000 police officers across the country, and a veteran police constable in Vancouver. He said his experience in the Lower Mainland is that "there are many other tactics that are used before police get to a dynamic entry." They still might involve police taking a battering ram to a door, but without officers in commando gear rushing in, guns in hand.

"You're just breaching the door, announcing after you've breached the door, to gain control of the premises," he said.

"The tactics have evolved, and like I said, the police are responding to the incidents that they're confronted with and we're using tactics that are hopefully keeping everybody safer."

WATCH: Police union chief says no-knock raids are largely safe:

Kevin Cyr, head of the RCMP's tactical unit for B.C.'s Lower Mainland region, said he can think of just one full-on dynamic entry that his team did in the last year, and it wasn't a search for drugs.

"There was a day when every agency, all you did was dynamic entry for drug warrants. And the thought was it’s effective because by surprising a suspect, you can stop them from disposing of drugs," said Cyr, who also has a master's degree in law and writes in academic journals about policing.

Under its current, more restrained approach, he said his team has missed out on seizing "significant amounts of fentanyl" or other drugs in a few cases, including one just last month.

"There is a significant social cost. There's also a benefit of reducing the danger of these search warrants," Cyr said. "You can prevent someone from destroying evidence, but is it worth the risk?"

Back east, though, the tactic is alive and well.

V. The informants

Christopher Woof, who raps under the name Prezzy, was just about to get into the shower on a balmy morning last July. Suddenly, he heard an ear-cracking explosion, then seconds later was faced by tactical police, their guns directed at his bare body.

"I was literally held there naked, with machine guns pointed at me, for several minutes. They wouldn't let me move or even cover myself or nothing," Woof said.

WATCH: Ottawa police storm a home looking for drugs:

Officers had bashed in his front door and set off a flashbang grenade. It was part of an investigation involving the same Ottawa drug squad that, three months later, would orchestrate the raid on Anthony Aust's family apartment.

They arrested Woof and led him outside. Then they searched his house and drilled holes in his walls looking for crack, cocaine and guns. They didn't find any, but they did find about 70 OxyContin pills and thousands of dollars in cash.

Woof said the pills were from prescriptions he got years ago after surgery following a motorcycle crash. He showed CBC photos of his damaged walls and X-rays of his broken right wrist and shattered left shoulder. The money, Woof said, is from his contracting business, where he often deals in cash.

He was taken to a police station and led into a small room. That's when, he said, two detectives made him a proposal.

"They offered me money and protection, and they offered me to leave with absolutely no charges," Woof said. "They said that I'll get $2,000 for every tip that I give them."

The alternative? "They said if I don't agree, they're going to slap me with some charges. And they're going to make it hard for me, I'll never travel again."

Woof said he treated it like a joke because he was confident officers wouldn't find anything illegal in his home.

But he was charged with possessing the OxyContin with intent to traffic it, and with possessing crime proceeds of over $5,000 for the cash. His case is still before the court.

The Ottawa Police Service did not respond to questions regarding what occurred with Woof, but said it will address concerns around dynamic entries once a report on the issue is filed at its next board meeting, on March 22.

What Woof didn't learn until well after his arrest is that the very police he said were leaning on him to snitch had relied on a confidential informant to build their case against him in the first place.

Sometime last May, the Ottawa drug squad developed a new source, a person "familiar with" cocaine, crack, methamphetamine, prescription pills and cannabis, according to allegations police filed in court. The new informant stood to get paid for correct tips they provided, even hearsay information. Their very first tip was about Woof, alleging that, under his stage name Prezzy, he "brags about how much money he makes from rapping and selling cocaine and crack cocaine."

Based on the tip and subsequent surveillance on Woof, a justice granted a search warrant. Woof had no criminal record, there was nothing in the Ottawa police database to suggest he was involved in narcotics and there is nothing in the warrant to suggest he had any guns or weapons.

Police nevertheless brought in the tactical unit for the safety of officers and whoever was in the home, and to "protect the imminent disposal and/or destruction of evidence," they say in their court filing.

Woof said it was the type of quasi-military operation he imagines in a hostage taking or terrorist situation, with 10 officers in tactical gear sent into his home. "They did it with no reason to do it, and that's scary.… It's dangerous, what they're doing."

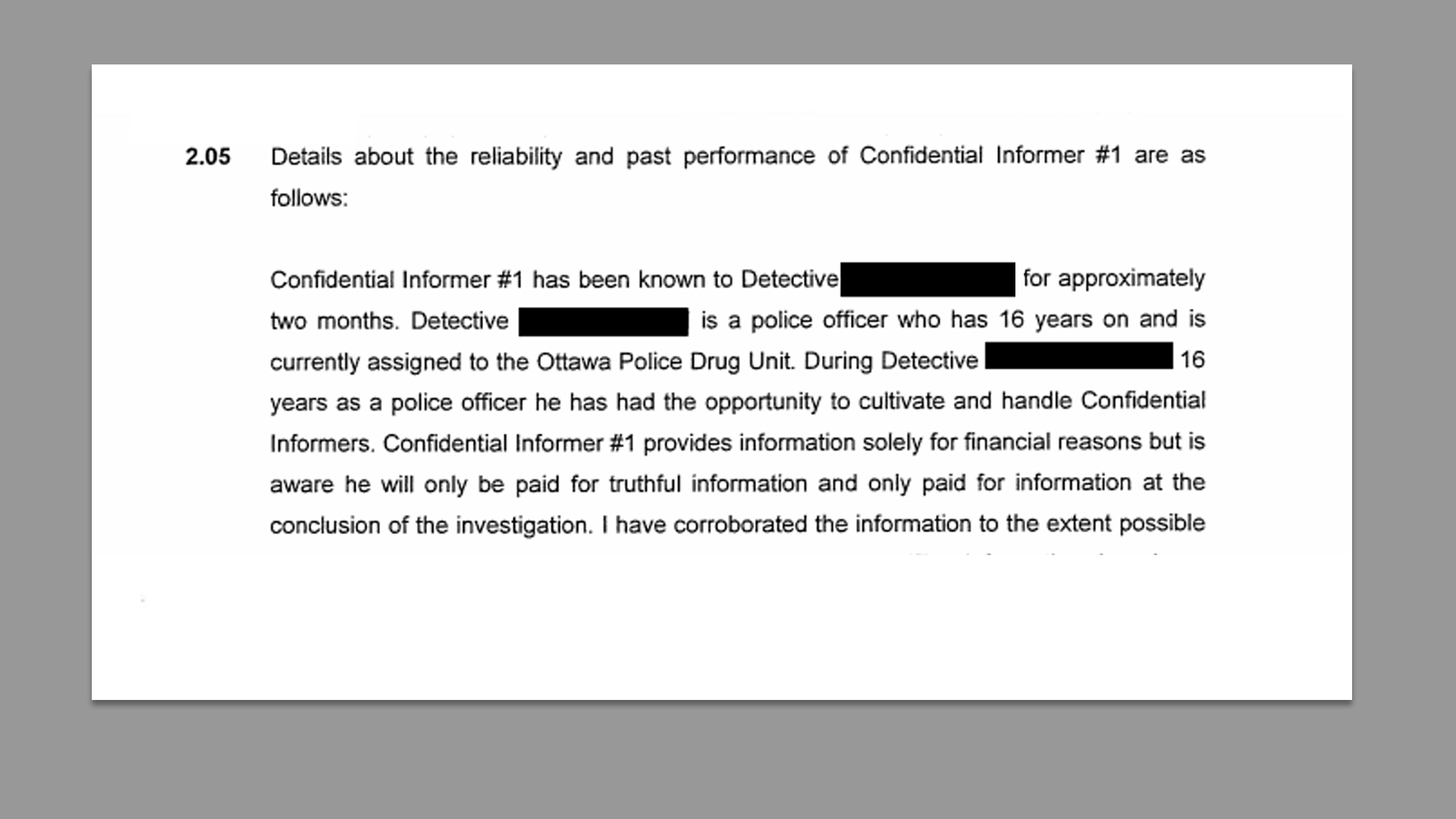

The Fifth Estate has reviewed the court files on three other Ottawa no-knock raids in the last five years, including the deadly dynamic entry at Aust's apartment and the middle-of-the-night, futile search for explosives at Schneider and Wiseman's home. In all of them, police relied on confidential informants — whose names are almost never disclosed to anyone — to get search warrants. In all of them, the tips were at least partly wrong.

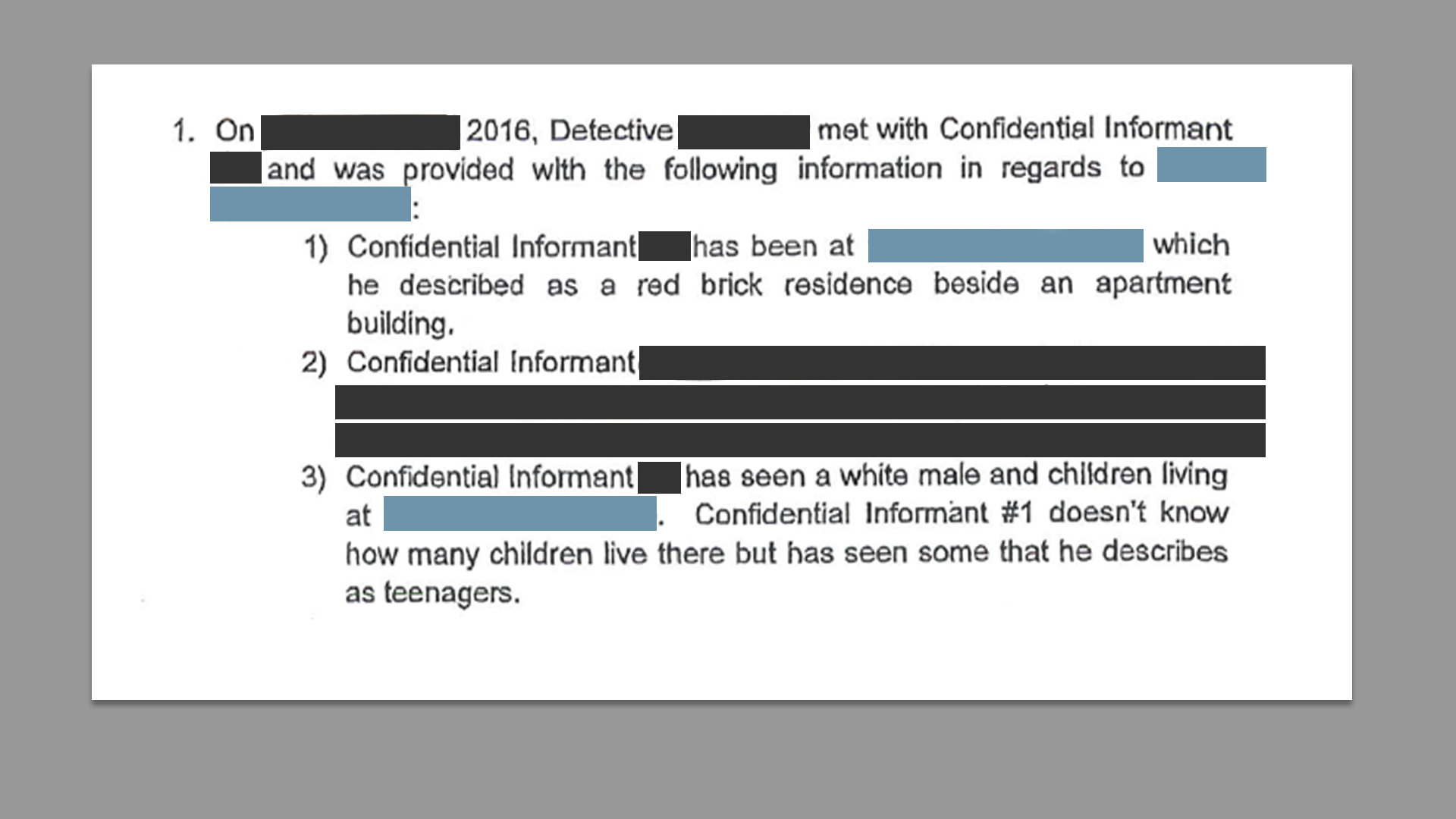

In Schneider and Wiseman's case, it was also a single, paid informant. The person was "familiar with various controlled substances," police said in their search-warrant application, and with "various firearms and sources of ammunition," too. But the exact details of what they claimed to know about any guns and munitions at Schneider and Wiseman's home are blacked out in court records.

Detectives did do a bit of independent legwork: For about eight hours before they raided the house, they put the family under surveillance. What did they observe? "Kids ranging from eight to 15 years playing in the front yard," Wiseman exiting the front door to talk to the kids, a teenager "going in and out" every now and then, Schneider arriving home in his GMC truck. In other words, a normal family.

Somehow, police formed the belief they would find an AR-15 assault rifle, .38 calibre handguns, other firearms, Tasers, ammo and grenades. They listed them all on the warrant.

"They acted on a tip from a confidential informant, which makes no sense to me. Because if that was me, I could say that anybody is doing something wrong and they'll just go kick their door in," Schneider said. "There was no tangible evidence."

The Ottawa Police Service wouldn't comment on the case, citing the report about dynamic entries expected at its board meeting later this month.

VI. SWAT state of mind

That act — kicking down doors, rushing in with guns drawn in a tightly choreographed display of overwhelming force — is itself relatively new.

Police tactical teams only began in earnest in North America in the mid-1960s, initially to deal with a rash of bank robberies (in Philadelphia) and labour unrest (in Toronto). The proliferation of the no-knock raid soon followed, as the U.S. war on drugs picked up in the 1970s and '80s, according to several histories of policing. Numbers for Canada are elusive, but in the U.S., by one count, about 80 per cent of SWAT team deployments are for drug raids.

Defenders of the use of police tactical units say that despite the military-grade arsenal and methods, they actually make for more peaceable resolutions to potentially combustible situations.

WATCH: Tactical trainer takes a SWAT team through use of real flashbang grenades:

Kevin Cyr, head of the B.C. Lower Mainland RCMP tactical squad, said SWAT teams use that equipment to mitigate risks, which "creates the time and distance necessary" to de-escalate an incident. He gives the example of someone who has barricaded themself inside a home with a gun.

"If I can bring an armoured vehicle there, my negotiator can spend all day talking to that person, without worrying about being shot at," Cyr said.

Tactical teams also tend to have more use-of-force options available, he said, specifically less-lethal ones like teargas, rubber bullets or beanbag rounds.

But critics say the risk of more heavily armed, martially trained police is that there will be more police violence in society, not less.

Kevin Walby, a professor of criminal justice at the University of Winnipeg who has researched no-knock raids, said the core ethos of community policing is supposedly to use the least force to achieve the greatest compliance with the law, whereas with SWAT teams, their guidelines are more militaristic, emphasizing "elimination" or "extinguishing" of threats.

"The use-of-force model that they're working with is already ratcheted up,” Walby said. “Their whole terms of reference is much less about locating evidence for prosecutions in the serving of a warrant…. The focus on threat elimination is much more prominent."

Walby said he's concerned that he's been seeing members of the Winnipeg police tactical support team on a wider range of deployments than in the past. His research found they were also staffing community patrols and traffic duties. "It might raise questions around what kinds of policing styles and technologies do they bring to those encounters," he said.

"But the most palpable, corporeal risk is increased risk of police violence. Which we know isn't actually a risk experienced equally by all — it's a risk that Indigenous and Black Canadians will face in an unequal manner."

Even where there isn't direct violence, there is often trauma.

WATCH: Kelsie Raycroft and Sam Bahlawan say they were 'terrorized' by Ottawa police the night they stormed through their home:

Sam Bahlawan and Kelsie Raycroft are another Ottawa couple whose home Ottawa police barged into without warning. A single, paid confidential informant had told police that their daughter's boyfriend was stashing drugs there. Officers conducted surveillance on their daughter and her boyfriend over several weeks before getting a warrant to search for cocaine and crack.

They executed the warrant one evening in November 2016, breaking down the door and setting off a flashbang in the entryway.

"He starts saying: 'This is a crack house, everybody on the floor! You're all a drug trafficker,' " Bahlawan said of one of the constables who had barged into his home.

Bahlawan and his son were forced to lie on their stomachs on their ground. His son was handcuffed behind his back. Raycroft, who had recently had heart surgery, was allowed to sit up.

Their daughter, Tamara Bahlawan — the person under investigation, the very reason police were searching the house — wasn't home. And police knew it, because they had been conducting surveillance on her for the prior hour.

"They could have knocked on my door. I would have let them in," Raycroft said. "I would have respected the warrant, and they could have gone through and looked wherever they wanted.

"I was terrified. I was going through so many emotions at that moment."

Police didn't find any drugs. They did find a handgun hidden in Tamara Bahlawan's basement bedroom. But Justice Sally Gomery acquitted her in December on firearms charges, finding prosecutors didn't prove she knew about it and it was quite possible her boyfriend had secretly stashed it there. It's the same case where Gomery scolded Ottawa police for their "assumption that they should break in the door of any residence that they have a warrant to search."

WATCH: Lawyer Mark Ertel says Canada’s 'war on drugs' underscores an increase in the use of no-knock raids:

Neither Sam Bahlawan nor Raycroft has received an apology from the force. Raycroft said she had nightmares for weeks of police breaking into their house. "It just rears its ugly head every once in a while, and you can't move on because there's no accountability."

Bahlawan, who immigrated to Canada from Lebanon in the 1970s, said he didn't feel he was in Canada that night.

"It's like my old country where I came from," he said. "They rush in, they do whatever they want because someone phoned and informed on you.

His daughter's lawyer told CBC that among the dozens of no-knock raids he's heard about from his clients, trauma is a common byproduct.

"People whose homes are entered in this way, they don't recover from it," defence lawyer Mark Ertel said. "They could be sitting in their living room watching TV and have a flashback of this bomb being thrown in their house."

He said he'd like to see Canada move toward the model in most U.S. states, where a judge or justice of the peace has to sign off on forced entries except in true emergencies. Federal law should also be amended to clarify when judges should grant that authorization, Ertel said.

"We have to decide as a society how important is it to us to secure evidence, every bit of evidence, and how much of the sanctity of the home are we prepared to sacrifice."

- Watch full episodes of The Fifth Estate on CBC Gem, the CBC's streaming service.