July 18, 2021

For Karihwakatste Deer, reclaiming land traditionally a part of her community has brought a sense of family, connection, and peace.

“We come from the land,” she said.

“Our language comes from the land, our culture, it's all connected to the land, and we need that connection.”

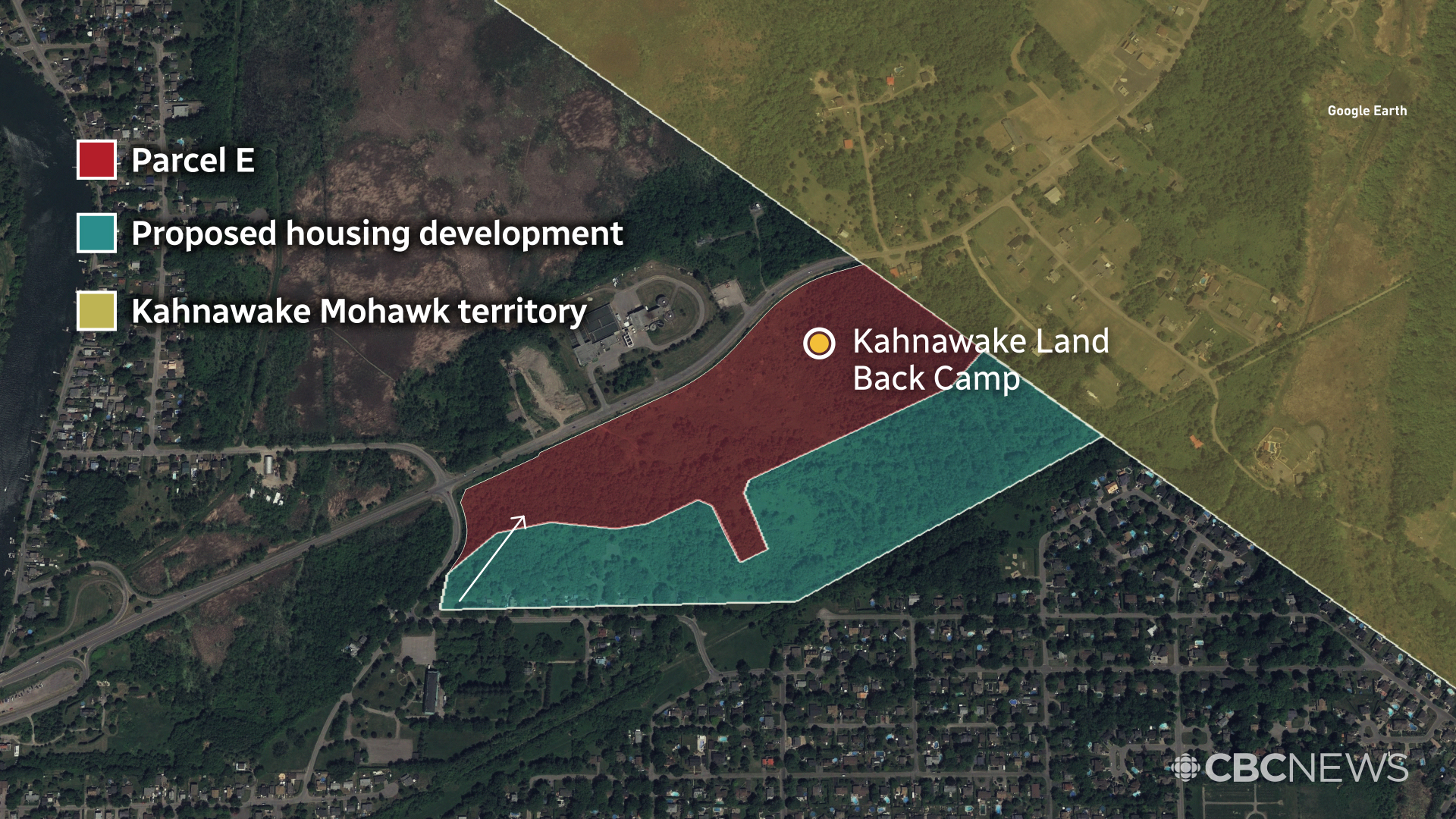

She is among a group of Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) of Kahnawake, south of Montreal, asserting jurisdiction beyond reserve boundaries to prevent a housing development slated in the neighbouring municipality of Châteauguay, Que.

On July 1, the Rotisken’rakéhte — the traditional vanguard of the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation — led a group of community members to re-occupy the wooded area.

It comes months after the municipality approved a zoning change on March 15 that would allow for the construction of 290 single family homes, semi-detached houses, and row houses, sparking opposition from the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation at Kahnawake — the traditional governing body that preceded First Nations band councils.

‘It means taking back what's ours, what was originally ours,’ said Karihwakatste Deer.

“Especially this land because it's connected to Kahnawake. It's still undeveloped and we have the chance to actually take it back in its natural form.”

Every day since, people gather around the main camp’s fire to talk about history and current affairs. Others are spending their time at smaller camps pitched further into the bush, tanning moose hides and learning about the natural habitat. The Rotisken’rakéhte patrol the area.

“Just being here on the land, being in the bush with nature, with all of the medicines and the fruit trees that are out there. It's really good,” said Karihwakatste Deer.

“It's peaceful to be here.”

The land, which spans two properties, is among the few undeveloped areas remaining along the Kahnawake and Châteauguay border. Plum and apple trees are scattered throughout the area, as well as raspberry and blackberry bushes. It contains two wetlands.

“It's a beautiful area and it would be terrible if it were destroyed for a housing development,” said Teiowí:sonte Thomas Deer, communications co-ordinator for the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation Office.

“Children are running around and playing on the land, learning about what it means to be Onkwehón:we (Indigenous). It is inspiring.”

The goal of the camp is to show Kahnawake’s presence on the land before any development happens — something turtle clan mother Kaheríhshon Fran Beauvais hopes will thwart confrontation or violence with stakeholders in the project if the development proceeds.

“We're here because we need to be here,” said Beauvais.

“The land base that we have is so tiny compared to what is originally owed to us. If we allow the encroachment to continue, they're going to take everything.”

341 year-old grievance

The Mohawk Council of Kahnawake — the elected band council — also expressed opposition to the housing development, as it is a stark reminder of an unresolved 341-year-old land grievance.

A seigneury, a land tenure system that was used by the French Crown, was granted by King Louis XIV of France in 1680 to the Jesuits for setting up a mission and for the use and occupation of Kanien’kehá:ka of Kahnawake.

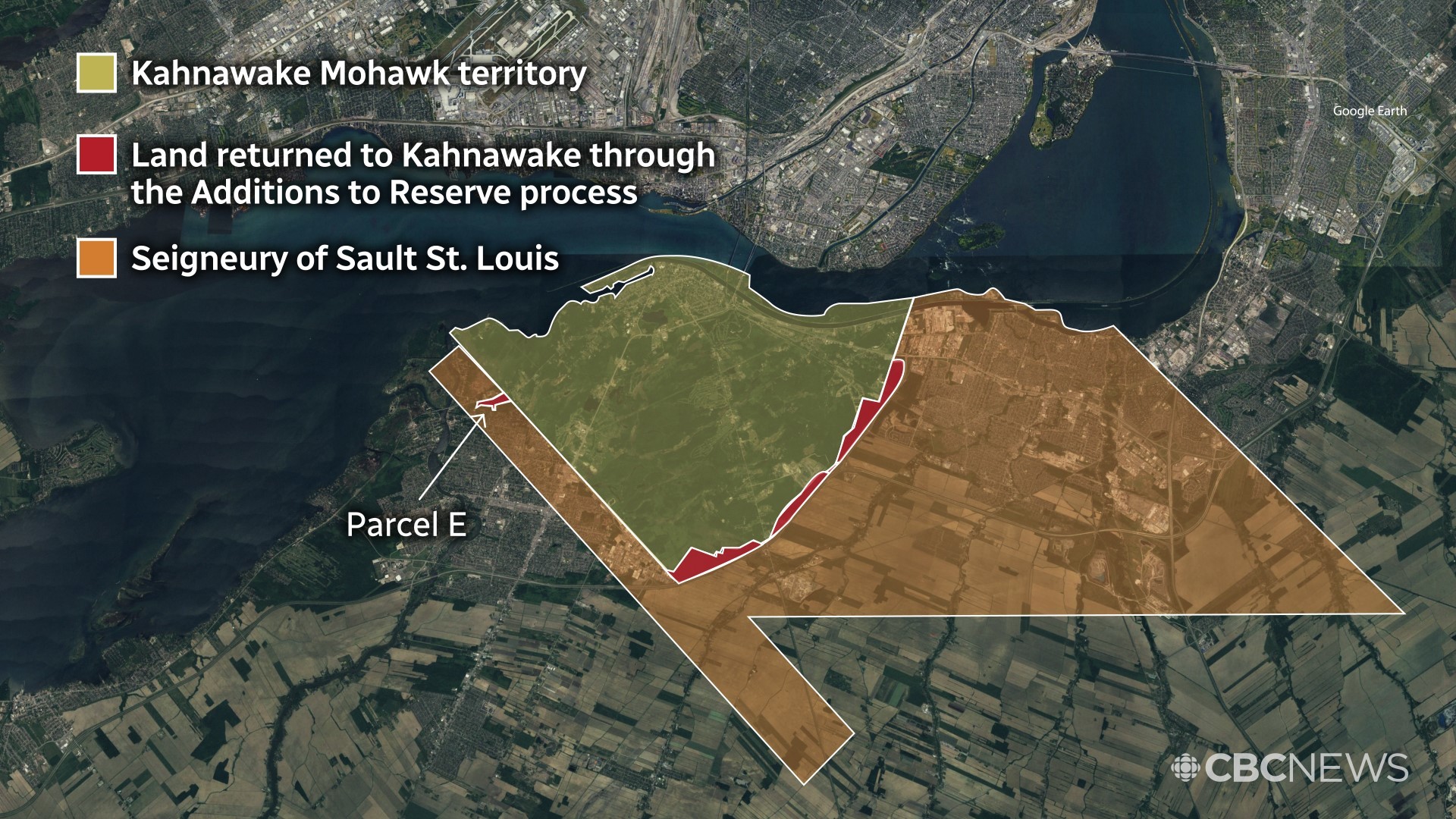

A long documented history shows the community’s concerns about the dispossession of lands designated to the Seigneury of Sault St. Louis. Once spanning 18,210 hectares, Kahnawake’s land encompasses less than 5,261 hectares today. The vast majority of the seigneury lands have been developed by multiple municipalities across Quebec’s Monteregie region.

The federal government agreed to negotiate the grievance under Canada’s Specifics Claims process in 2003 but Mohawk Council of Kahnawake chief Mike Delisle Jr. says there’s been no progress since 2015.

“They've actually taken massive, monumental steps backwards,” said Delisle about the federal government.

“Personally, it makes me extremely angry.”

In 2007, the Quebec government promised the return of 283 hectares of land in exchange for the expansion of a provincial highway that runs through seigneury lands. Roughly 200 hectares officially completed Canada’s additions to reserve process, including Parcel E where a part of the reclamation camp is located.

Quebec still owes 85 hectares. Through community consultation, getting land back has always been a priority for Kahnawake.

“The community said land is number one, money is a distant second,” said Delisle.

“That's the marching orders that we've been carrying and following… that's still the direction that we're taking, whether it be this land or any other land in the future.”

For traditional leadership, it’s important not to be pigeonholed by the parameters of the seigneury. Traditional Kanien'kehá:ka territory spans 3.6 million hectares of land stretching from the St. Lawrence River Valley through the Adirondack Mountains and Mohawk River Valley in upstate New York. It remains unceded.

“The King of France was in no position to give us land that already belonged to us,” said Teiowí:sonte Thomas Deer.

“However, we acknowledge that it was the responsibility of each succeeding colonial regime to prevent encroachment on those lands. These regimes did not fulfill that responsibility."

Land Back

What is happening in Kahnawake is a part of a growing ‘Land Back’ movement.

The Yellowhead Institute, a First Nations-led research centre based at Ryerson University in Toronto, published a 2019 report on land dispossession, identifying re-occupations of land as one of the most direct assertions of reclamation with examples growing in numbers and scope across Canada.

“One of the things that I think is really powerful about re-occupying the land and these movements is how inspirational they can be,” said Hayden King, executive director of the Yellowhead Institute.

“Re-occupying the land has this tangible, visible, visceral outcome.”

King said the avenues Indigenous Peoples have to reclaim land are often limited, and re-occupation is becoming more successful at stopping development.

- READ MORE: Year-long Six Nations protest forces cancellation of major development in Caledonia, Ont.

“If you look at the history of this country, any progress on Indigenous rights has been made through confrontation. And a lot of that confrontation happens on the land,” he said.

“We see what people are doing across the country. It inspires others, and it shows people that it can be done.”

For Teiowí:sonte Thomas Deer, he feels land reclamations will likely be the only way to sustain Kahnawake’s growing population.

“Onkwehón:we people cannot rely on the government of Canada or its provinces to achieve land justice,” he said.

“Only through acts of self-determination, can Onkwehón:we people restore their territorial integrity.”

The Kanien’kehá:ka Nation Office and Mohawk Council have sent letters to various levels of government over the last five months. The developer, who has owned the land adjacent to Parcel E since 2016, did not respond to a request for comment.

The City of Châteauguay said in a statement that apart from the amendment to the zoning bylaw, no other steps have been taken so far concerning this residential development.

Mayor Pierre-Paul Routhier said he recognized the opposition to the project stems from historic unresolved land claims, and said the city will be writing to the federal and provincial governments “so that they can respond quickly to the demands of our neighbours.”

The Office of the Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations, however, said in a statement that Canada encourages the Mohawk Council of Kahnawake to continue dialogue with the municipality and province, as the development project is situated on provincial lands.

“They pass the buck, and what they do is they try to tire us out,” said Beauvais.

But no one is giving up anytime soon, she said.

They plan to keep the encampment going until they receive word that the housing development is shelved for good, and the land is returned to Kahnawake.