May 17, 2018

Amanda Wahobin wants her purse back.

The bag, currently being held by police, is Wahobin’s last connection to her late boyfriend Brydon Whitstone, who was fatally shot by the RCMP in North Battleford last fall.

“I’d have a part of him with me still,” she says.

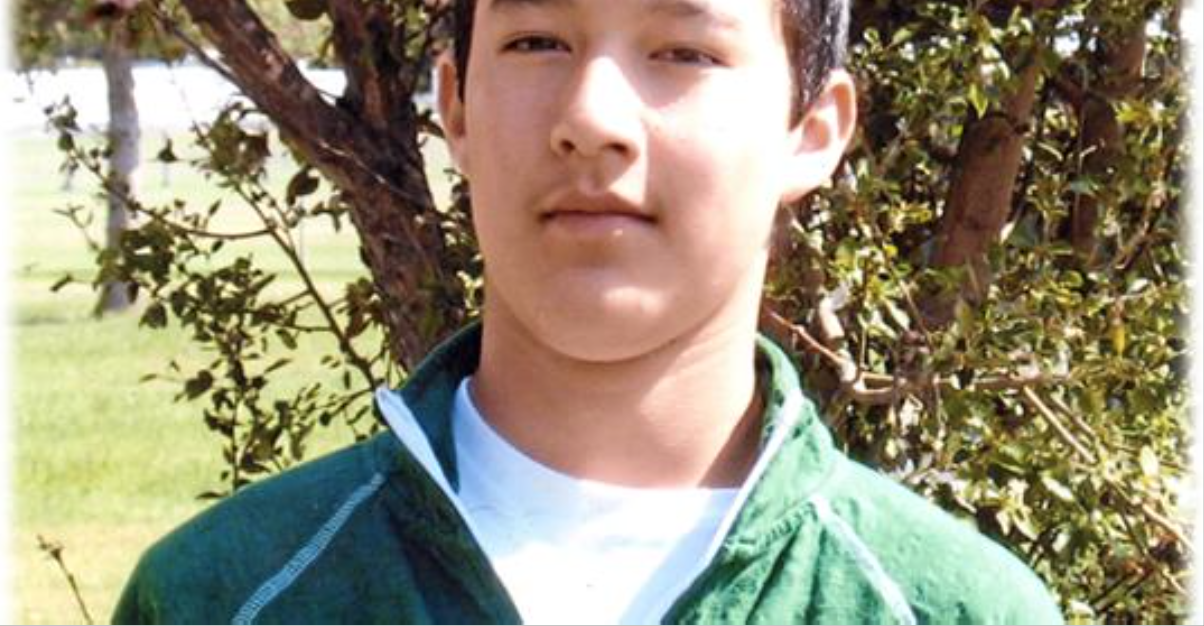

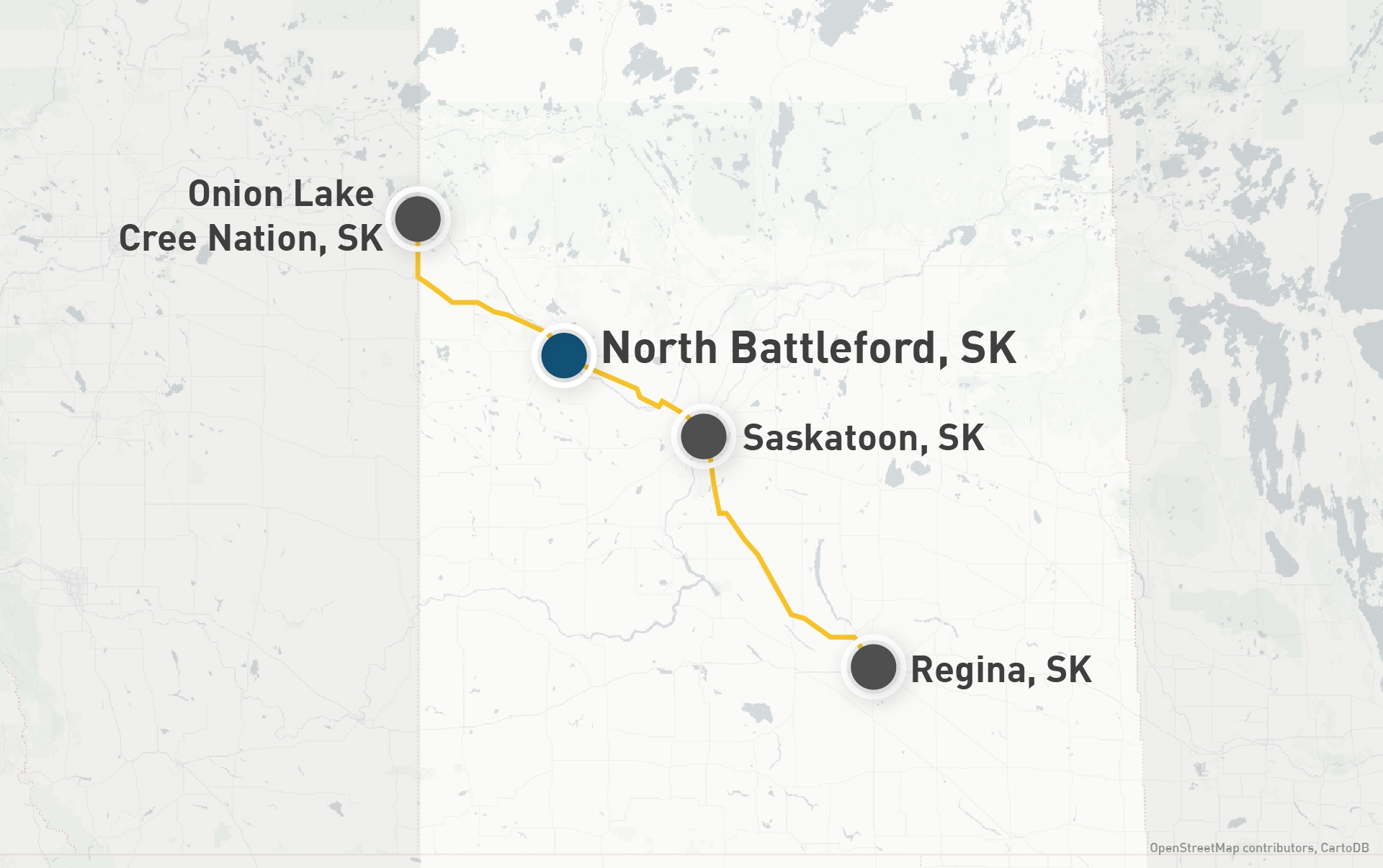

Whitstone, 22, was from Onion Lake Cree Nation. He and Wahobin, then 28, had been dating about four months on Oct. 21, 2017, the night of his death.

Earlier that evening, Whitstone stood in Wahobin’s home and took off his watch, bracelet and rings, which Wahobin put in her purse reluctantly.

“I want you to keep these in case anything happens to me tonight,” she remembers him saying.

Whitstone was dead about a half hour later, Wahobin estimates.

Wahobin watched from a passenger seat as Whitstone refused to stop for an RCMP vehicle, led police on a high-speed chase through several residential blocks of North Battleford and collided with at least one RCMP vehicle before coming to rest near an intersection.

She says neither she nor Whitstone had a gun when confronted by the RCMP, but that Whitstone acted in a way that may have led officers to believe he did.

“He was pretending he had something,” Wahobin said.

“That’s when I heard the cops saying, ‘He’s grabbing a gun, he’s grabbing something, he’s grabbing something.’

“Then they shot him.”

The first question asked of RCMP Chief Supt. Maureen Levy at a news conference the next day was whether police had found a weapon in the car.

Levy, the officer in charge of criminal operations in Saskatchewan, wouldn’t answer that. Nor would she say how many shots were fired by police or how an RCMP member became injured during the chase.

The investigation into Whitstone’s shooting had already been taken out of the RCMP’s hands, Levy said.

“I sound like a broken record here,” said Levy, “but I’ll be perfectly honest: all of that information will be sussed out by Regina Police Service in their investigation.”

The RCMP press conference the day after the shooting

According to Levy’s prepared statement, the RCMP responded to a call that night from a man who claimed he had been shot at by people in a car.

RCMP members spotted the vehicle Whitstone was driving and “initiated a brief pursuit, which ended shortly after the suspect vehicle rammed the police vehicle and became immobilized,” said Levy.

An RCMP member then fired a weapon “in response to the driver [Whitstone’s] actions,” she said. “Mr. Whitstone died as a result of his injuries.”

A 45-minute gap

The RCMP said little else about what happened during the 45-minute period between 8:55 p.m. CST — around the time the RCMP received the shooting complaint — and 9:40 p.m., when Whitstone was pronounced dead en-route to the hospital.

But Wahobin, who spent Whitstone’s last few hours with him, has given CBC News her first-person account of what happened that night.

Whitstone’s death came just as he had turned away from his former life as a gang member, according to both Wahobin and Whitstone’s family.

He was also dealing with mental health problems and an addiction to meth, according to Ron Piche, a lawyer recently hired by the Whitstone family.

“He had fought those demons and was getting on with his life,” Piche said.

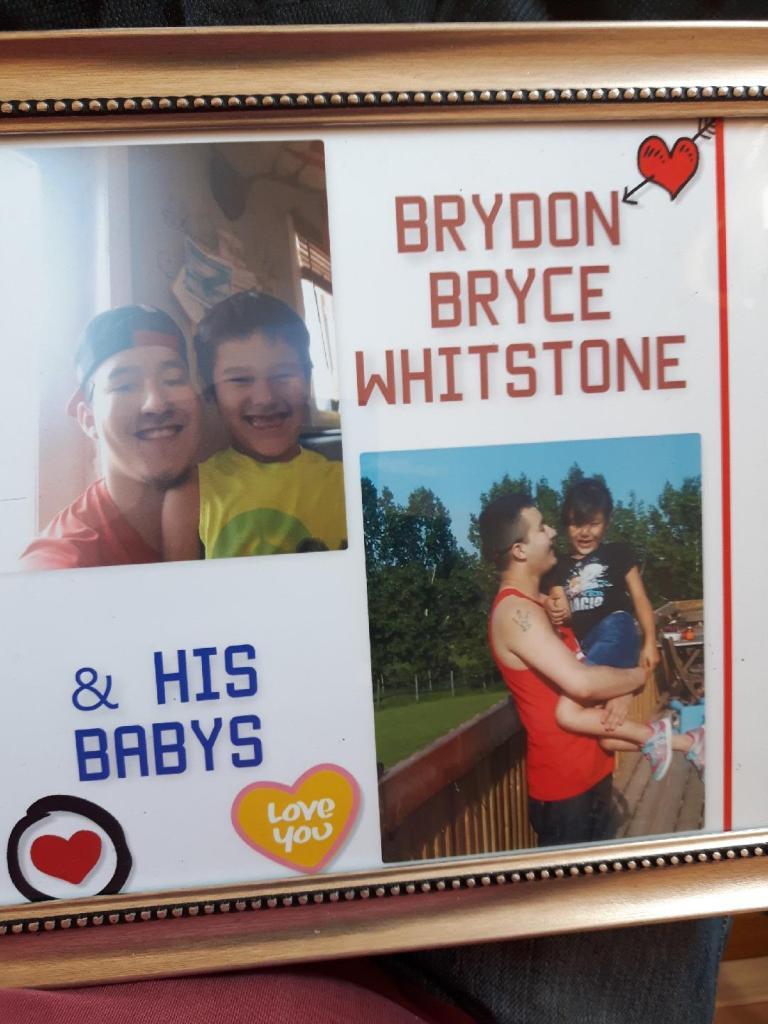

Whitstone’s older sister Nikita Cook said the death the previous month of Whitstone’s newborn son, Brydon Whitstone Jr., was a turning point.

“After that happened was where he wanted to change his life around,” she said.

His first two children Orianna and Merlin, who lived in Onion Lake, were on Whitstone’s mind, Cook said.

“He would do anything for his kids. And it bugged him more that he couldn’t see them because of the lifestyle he was living,” said Cook.

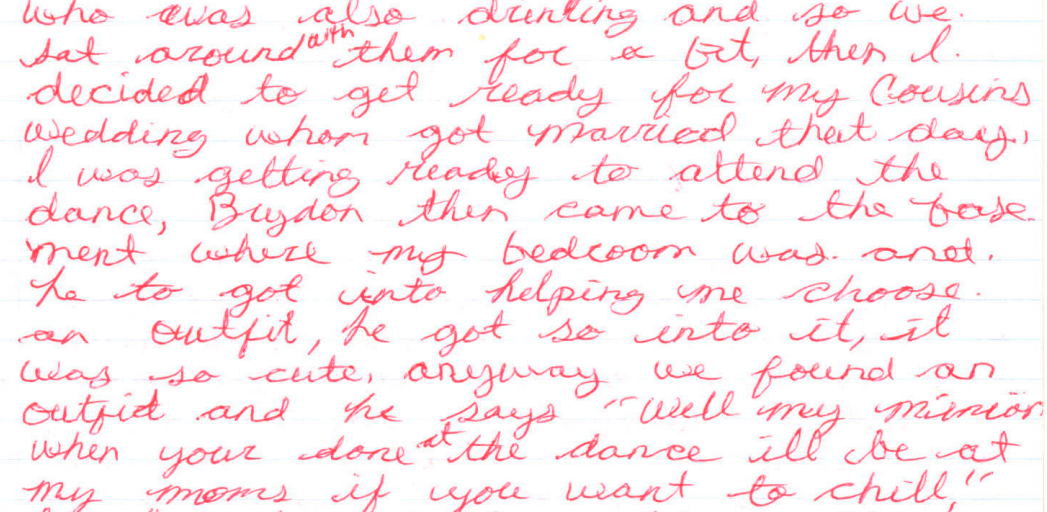

Whitstone’s desire to turn things around came up on the night he died, according to Wahobin, his girlfriend of about four months.

At the 106th Street house where Wahobin was staying, Whitstone helped her pick out a dress for a dance that night. He’d agreed to be her date.

“He got so into it. It was so cute,” she recently wrote from Prince Albert’s Pine Grove Correctional Centre, where she was serving a sentence for a robbery conviction unrelated to Whitstone’s shooting.

Later, while smoking in front of the house, Whitstone talked about “making a better life for himself,” said Wahobin.

“No more gang activity and no more drugs,” she recalls him saying.

Some time between 9 p.m. and 9:30 p.m., Wahobin and Whitstone noticed police cars driving down nearby 11th Avenue, she said.

Back inside the house, after Wahobin got her purse from the basement, she saw Whitstone in the living room removing his jewelry.

The couple then headed on foot towards Whitstone’s mother’s house to pick out something for him to wear at the dance. As they walked down a back alley, a friend of Whitstone’s drove by in a white car, Wahobin said.

Police considered Whitstone's car a "suspect vehicle" in an earlier reported shooting

The friend allowed Whitstone to borrow the vehicle but warned Whitstone to stay away from an area with police, according to Wahobin.

Wahobin said Whitstone knew the car was stolen. She said Whitstone drove past his mother’s house, which Wahobin thought strange but didn’t say anything.

An RCMP vehicle passed them shortly after that, she said.

“I was like, ‘Please don’t turn around.’ And it ended up whipping a [U-turn],” said Wahobin. “Then the cops ended up turning on their lights.”

'He wouldn't stop'

Whitstone had been in jail and didn’t want to go back, Wahobin said. She herself was breaching a conditional sentence order.

“[Brydon] always told me that if cops came, he wouldn’t stop. That’s when we started cruising and that’s how the high-speed chase started.”

Whitstone almost ran into a car backing out of a driveway at one point, Wahobin said.

He did hit an RCMP SUV on 15th Avenue, at the end of an alleyway between 104th Street and 105th Street, said Wahobin, claiming Whitstone did not intentionally ram it.

Photos taken the next morning show an RCMP vehicle had been propelled into a house yard.

Wahobin said the collision with the SUV triggered the car’s airbags, briefly knocking her out.

She said she thinks Whitstone may have then run into a second police vehicle. Photos taken the next day show part of the bumper missing from another RCMP SUV.

Whitstone drove around the block before the car finally came to a rest at the corner of 105th Street and 15th Avenue.

There, on the front lawn of the Academy of Learning, RCMP officers quickly surrounded Whitstone and Wahobin, she said.

“They were just telling us to stop and get out of the vehicle. But Brydon just kept putting it on reverse and drive, reverse and drive. He wouldn’t stop.”

Wahobin said the RCMP shot something into the car, possibly tear gas.

“I could see the smoke,” said Wahobin. “Brydon grabbed my head and he put it on his stomach and he said ‘Try not to breathe this stuff in.’”

Cpl. Rob King, a media relations officer with the RCMP, says tear gas is not typically something front-line officers have available to them but that they may have other “intervention options” at their disposal, including Tasers, pepper spray and batons.

Wahobin said Whitstone then used his right hand to dig into the front of his pants, “pretending to grab something.”

“I could hear the policeman yelling, ‘He’s reaching for something.’”

2 gunshots

Wahobin said she heard a gunshot and Brydon groan.

Then — despite Wahobin again telling him to stop — Whitstone fiddled with the gears of the car more before again putting his hand in his pants, according to Wahobin.

“That’s when I heard the cops saying, ‘He’s shooting at us. He has a gun. I see the gun.’

“We had no gun."

Wahobin said she heard a second gunshot coming from [the direction of] the driver’s side window and saw Brydon’s head slump towards his left arm before she was finally pulled out of the vehicle.

Footage shot that night by civilian Summer Nicotine, while offering only a distant and unstable view, gives an idea of the hectic sounds of the scene: an engine revving and what sounds like more than one shot, followed by shouting.

Civilian video shot that night

Chief Supt. Levy said RCMP members immediately attempted life-saving measures to Whitstone until paramedics arrived.

The last time Wahobin saw Whitstone, he was being wheeled into the ambulance, she said.

Wahobin struggled when asked whether she feels the police’s actions that night were justified.

On the one hand, she said Whitstone had voiced suicidal thoughts before the day he died.

“I’m not the only one that knew he was suicidal. There’s a lot of us that knew that.”

Part of that was fuelled by the recent death of Brydon Whitstone Jr., she said.

“The position that I was in made me feel that it was suicide by cop,” she said.

“But then again, the officer was yelling that we were shooting back, that we shot fire at something and we had a gun. So it was wrong on both ends, I kinda think.”

Whitstone left behind his mother and father, his two children and many siblings.

Both his father Albert Whitstone and his older sister Nikita Cook said the suicidal Whitstone described by Wahobin does not sound like their loved one.

“He was never like that. He never thought of suicide or things like that,” said Cook.

Whitstone had friends who had taken their own lives, said Cook.

“He would more or less get mad at somebody for even thinking about suicide. He used to always call people a cop-out that would take the easy way out of life," she said.

Albert said his son planned to come back to Onion Lake this summer to spend more time with his kids, go back to school and pick up a trade.

He wants to know how and why his son was killed.

“There’s a lot of stuff I’d like to know,” he said. “Why that cop shot my son, and could he have used a taser or rubber bullets or whatever.”

Other man wanted for original shooting complaint

Some details have emerged about the alleged shooting the RCMP were initially responding to.

Cpl. King said that six days after the shooting, on Oct. 27, a warrant went out for the arrest of the man accused of shooting at a man from a car.

Dalton Checkosis is wanted on charges of possession of a prohibited weapon, carrying a weapon for a dangerous purpose and breach of a recognizance.

“His whereabouts are currently unknown,” said King on Tuesday.

A 'cone of silence' from police

The Regina Police Service finished its external investigation into Whitstone’s shooting more than two months ago. Two major crimes investigators were assigned to the investigation, and a third was tasked to be a liaison with the Whitstone family, according to police spokesperson Elizabeth Popowich.

“[The liason’s] function would be to try to give them as much information as possible without jeopardizing the investigation or precluding its outcome,” Popowich said in a March 15 email.

Albert said he hadn’t heard once from Regina police until about a month ago. That’s when he hired Piche, a Saskatoon lawyer, to advocate on behalf of the Whitstone family and potentially represent them in a wrongful death suit against the RCMP.

"The cone of silence as it relates to the family of the deceased is just not acceptable," said Piche.

Piche says the level of communication from Regina police has been “nil.” Whitstone's mother, Dorothy Laboucane, calls the wait for answers “torture.”

“We have been in contact with the family since last October,” said Popowich this week. “I would not be able to offer an explanation as to the family’s sentiments, such as you have described.”

File under review

Regina police’s findings have been passed on to the RCMP and Ministry of Justice.

They’ve also been shared with an investigation observer appointed by the ministry after the shooting to bring a “lens of independence” to Regina police’s work.

That observer is typically a former cop with major crime experience and, in this case, not a former member of the RCMP, according to the ministry.

Saskatchewan’s Police Act says the report delivered to the ministry by the observer is confidential. The ministry would not confirm last week whether it had even received that report.

'Show some respect'

Piche said that, regardless of what the legislation says, it’s “straight common sense” for the Regina Police Service “to show some respect” and talk about the findings with the Whitstone family.

“There’s an investigation that’s been completed. They’ve interviewed witnesses. They’ve reviewed forensics. They’ve spoken to the officers, no doubt.” said Piche.

“If there’s nothing to hide, then tell us what happened.”

Popowich says details of the investigation wouldn’t be discussed until testimony is given in a potential criminal trial or inquest.

“I believe there will be a public process in this case, so there will be an appropriate time and place to provide details of our investigation,” she said on Monday.

The Whitstone family lawyer, Ron Piche, questions the "cone of silence" around the case

The Ministry of Justice previously told CBC News that fatal police shootings also spark an “internal/code of conduct investigation” within the RCMP.

King with the RCMP said Tuesday the RCMP will wait to see what Crown prosecutors decide before potentially moving ahead with that internal investigation.

Even if Crown prosecutors decide no charges are warranted, King added, “we would still look at it again to see, was their a breach in our policies? Was there a breach in our things that we teach and things we find acceptable or not?”

'A traumatic event for everyone involved'

Some of the RCMP officers involved in the Whitstone incident went off duty and received peer-to-peer and HR support. That can range from medical help to psychological counselling, King said.

“This is a traumatic event for everyone involved,” he said, adding that officers generally cope in different ways.

“Some people can go through a traumatic event and they can handle it really well, they can rationalize their way through it and kinda don’t have problems with it. Other people — and it’s nothing to do with one way being right or one way being wrong — may handle it a different way.”

The officers who went off duty are now back at work, said King, though he would not specify when they returned or in what capacity they’re working.

The people who knew Brydon Whitstone have dealt with his death in different ways, too.

Wahobin spoke with a visiting elder while she served her sentence.

She told CBC News she wanted to speak out in order to dispel other versions of what happened that night. Some have blamed her for what happened, she said. Others are “just trying to blame the police.”

Whitstone’s father Albert performs a daily ritual at his home in Onion Lake.

“Ever since the funeral, I have my son’s picture right by my bed. It’s still there," he said.

“I usually just say, ‘Good morning son.’”