June 5, 2021

Warning: This story contains distressing details about residential schools.

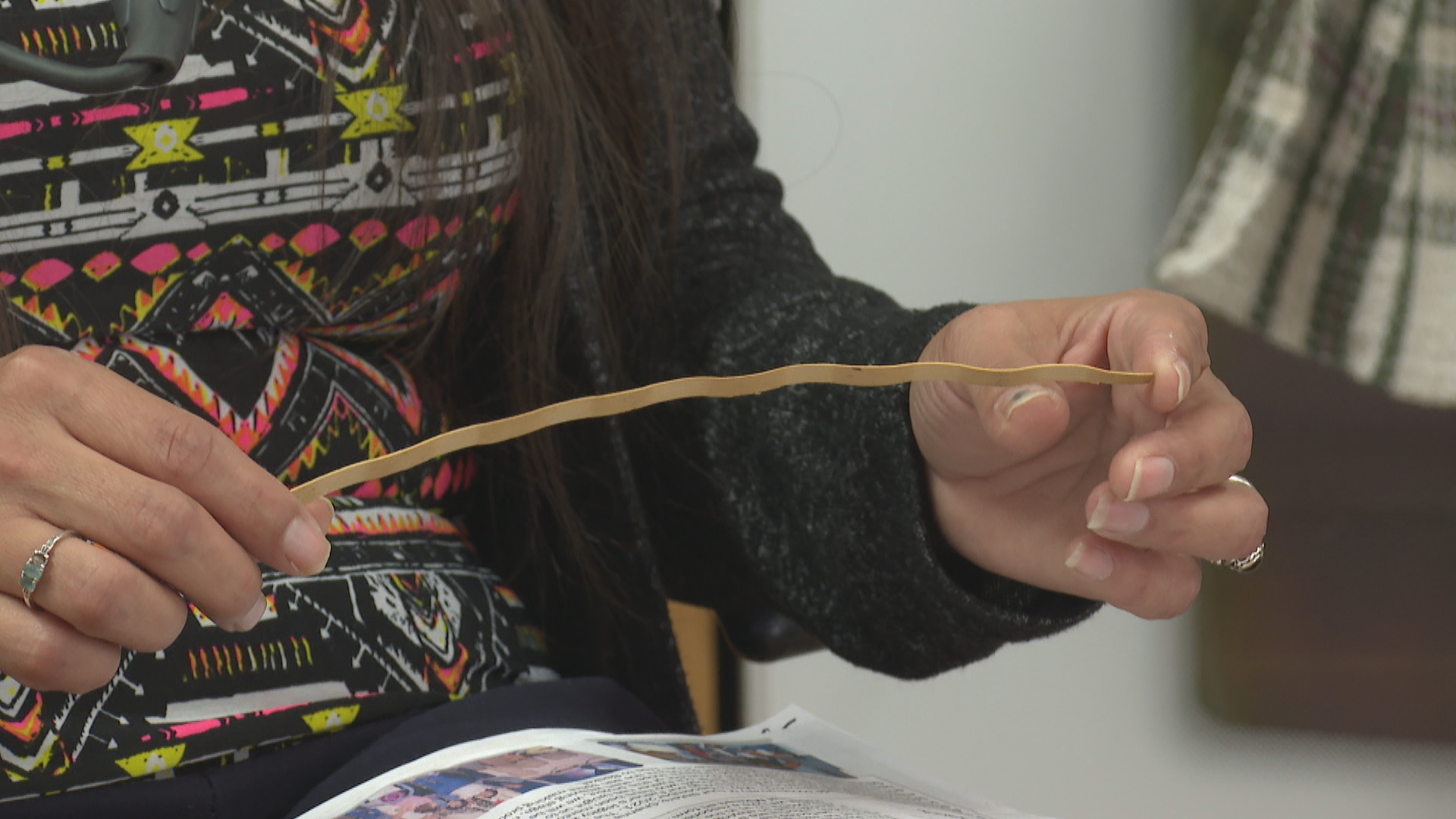

Madlene and Shanna Sark hold thin pieces of white ash harvested by their father for one of his baskets.

Madlene unweaves a piece or two each time the family wants the spirit of their father just a little closer.

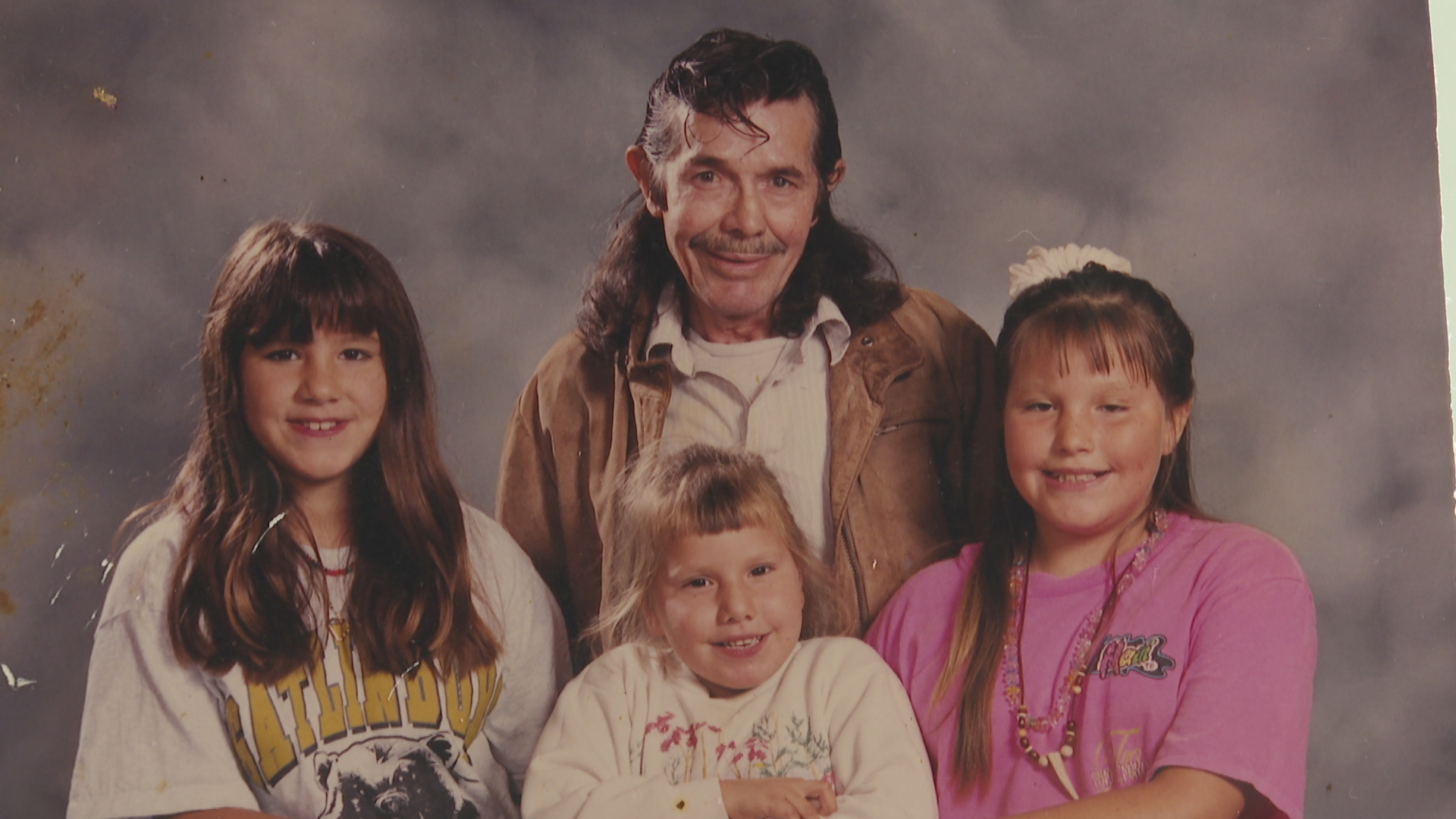

Gilbert (Tommy) Sark’s life was a mirror for many of the issues we talk about now through reconciliation. He died in 2013 at the age of 72.

Some of his children are working to share the story of the Mi’kmaw basket weaver and storyteller, putting a face to the pride and pain of the past.

“Before he passed, I had quite a few candid conversations with him,” Madlene said. "One of the things that he said to me, that he felt like was really important to him was that, 'Make sure the kids understand who they are.'”

Keeping traditions alive

Madlene and Shanna are at the youth drop-in centre in Lennox Island, P.E.I. Workhorses used as molds for Mi’kmaw basket weaving sit in one corner, a computer and gear to make rap and electronic dance music in the other.

The sisters sit between the traditional art equipment and today’s gear, right where they want to be as they begin a year-long project to bring the past to the future.

Their project, Unweaving Living Knowledge, is a tribute to a life shaped by residential schools, the reservation system, the Sixties Scoop and a fierce determination to keep the Mi’kmaw traditions alive.

“I could see a story behind dad's history and how he could actually overlay with our current history and how it's taught now. We don't have a specific history that's really being taught. And when I say specific history, I mean to Mi’kmaw, P.E.I., Epekwitk Mi’kmaw,” said Madlene.

Living on the land

Sark’s life began in 1940 in Breadalbane, P.E.I. It was home to one of the last encampments of the Mi’kmaw in the province. Many families were on reserves by then, with only a few left living in small shacks, tarp houses or teepees in the encampments.

“He told us quite a few stories about when he was younger and there was an old store there and a creek that he was by and they fished from.”

Gilbert’s mother passed away at the encampment before he turned three, he never knew his father. Still they were happy days on the eve of the darkest of his life.

Grandmother Issabella raised Gilbert to the time of her death two years later.

On his own at 12 years old

At five years of age, in 1945, Gilbert was forced into seven years at the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School in Nova Scotia. Despite efforts to rid him of his Mi’kmaw heritage, Gilbert held onto his language.

“The winter months when they would go outside and if they would come back in and they would have wet feet, they would get beaten with a ruler and sent to their room,” daughter Shanna said remembering stories her father told of the school. “If they bedwet the males would have to wear a dress and put the wet sheets on their heads and walk around.”

One day, at the age of 12, Gilbert could not take another beating.

“He just got sick of being hit with the ruler,” said Shanna. “So one day he said the nun was coming up and she was going to hit him and he said ‘I just took the ruler and I just broke it over my knee and I smashed through with it,’ and that's the time he actually got kicked out.”

Lifelong trauma

Gilbert wrote his memories of the residential school in more formal letters, and even small scraps of paper or inside the margins of other books.

“I don't want to say that there was good things about residential school,” said Madlene. “But he did learn how to write in English and he was able to articulate his past.”

The trauma led to a lifelong battle with alcohol, but also to beautiful art from his own hands.

When there were baskets there was peace

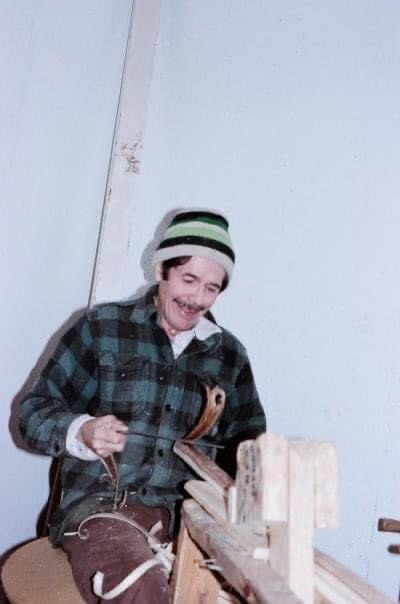

Young Gilbert began living at the Lennox Island First Nation. His extended family started raising him; the community helped too. It was uncle Mosey Sark who taught Gilbert the art that would help sustain his life, and create a legacy he passed onto others.

“I think it had something to do with his pain and something to cope with it and deal with it,” Madlene said of her dad’s love of basket weaving. “It was the art that he really, was really interested in and wanted to make it grow and become bigger than what it was.”

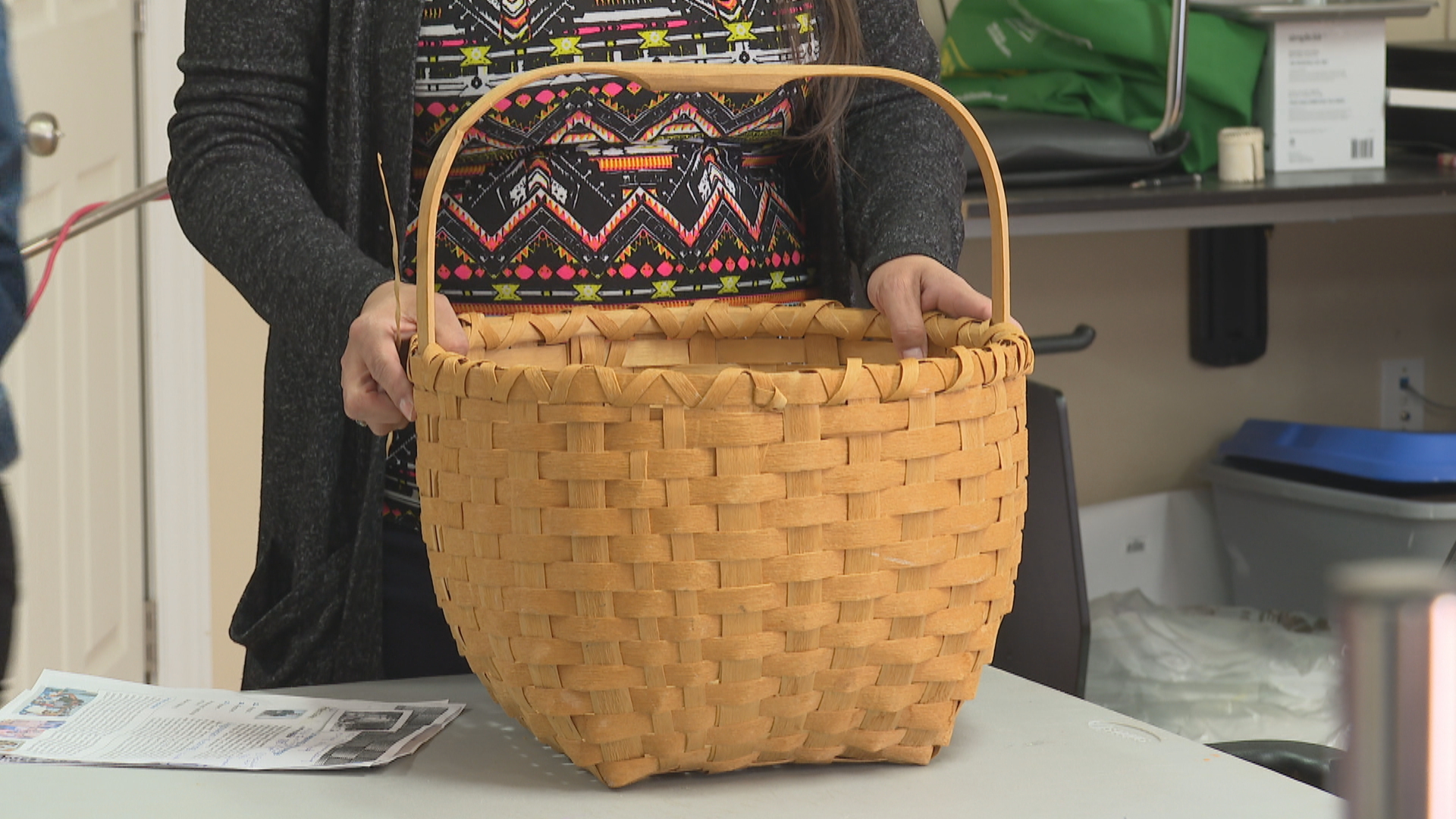

From start to finish Gilbert Sark’s baskets were all his. He harvested the white ash trees he could find on P.E.I., even if finding those ash trees would occasionally leave the artist face to face with an angry landowner. Gilbert grew up believing the land was a shared resource, and to never take more than you need and tread lightly.

He cut the strips, pounding them thin before weaving them into practical pieces of Indigenous art that are all over the world.

Madlene and Shanna can spot a “Tommy” basket instantly. He developed something called the “Tommy tuck,” a method to hide the bindings in the basket, and the ash strips look different too — he left them rough saying they would be more durable.

“It even helps with healing when you're weaving,” said Madlene of learning from their father. “We're weaving and we're sitting in shavings all around and there's strips everywhere. We had sweet grass around us all the time because he liked to adorn a lot of his baskets with sweet grass.”

A resident of Mi’kma’ki

Gilbert Sark moved throughout the traditional land of the Mi’kmaq, from P.E.I. to New Brunswick, into Maine and Nova Scotia, even Ontario.

Madlene and Shanna believe they have seven siblings, they found one since starting the research on their dad’s life.

“He's lived multiple lives, and so we were privileged to be a part of the end of his life,” said Madlene. “But there were a couple of different areas where we weren't a part of. Those are the parts where we're trying to pull [together] and there's people with stories out there.”

Some of their siblings were taken during the Sixties Scoop and adopted by other families after the provinces were given responsibility for the welfare of Indigineous children in the 1950s.

“That's why I'm saying, like, his story kind of coincides with some of the history. There it is again, right?”

Lessons for the future

In about a year, the sisters want to have a written history of their father. They plan to make videos about his past and create other web resources. They’ll learn how to make baskets from people Gilbert taught, they’ll visit the harvesting areas, and promise they’ll have four handmade baskets too.

The province of P.E.I. has already offered a grant to help pay for the work, and it will live as part of the province’s Indegenous art bank.

Shanna and Madlene hope one person’s past can inform a generation’s future.

“He was a broken man, yeah, but he was an inspirational man at the same time. And I've learned so much, probably more so since he passed, which is sad to say,” said Madlene, the small ash strip still held close.

Support is available for anyone affected by their experience at residential schools, and those who are triggered by the latest reports.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former students and those affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419.