June 17, 2018

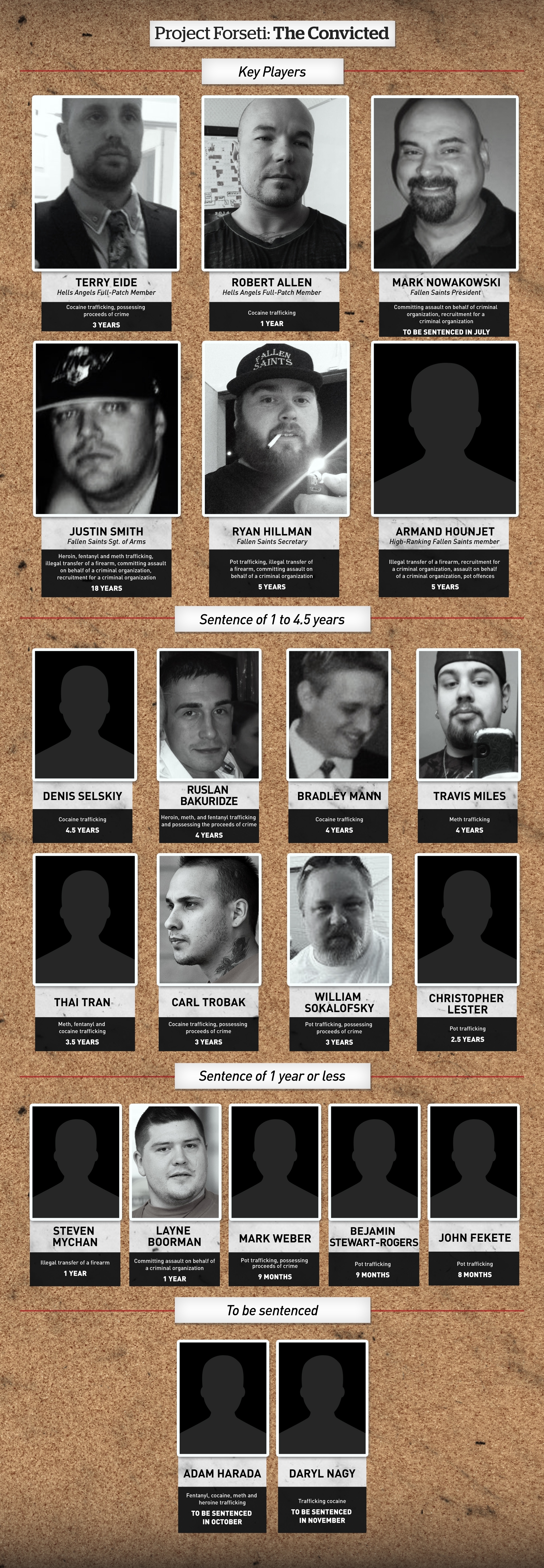

Noel Harder risked his life as a secret police agent, then spent three years testifying as the star witness against drug dealers, gun runners, mobsters and the Hells Angels.

Today he’s a marked man with an apparent $2-million bounty on his head.

And he’s on his own.

The RCMP kicked Harder out of the federal Witness Protection Program last month and, by his account, reneged on one promise after another.

These aren't just the words of a man labelled a "rat" and "snitch" after his double life was exposed; Harder served as the inside man on Project Forseti, the largest organized crime investigation in Saskatchewan history.

His allegations appear to be supported in a series of texts he received from a high-ranking Saskatoon police officer and a top federal Justice Department official.

"I'd never ever try to talk someone into going the agent route. It's a joke," the officer told Harder in a recent text obtained by CBC News.

Harder is not going quietly. He agreed to an interview with CBC News at a secret location. Those who want him dead already know what he looks like, he said, and they may even know where he is.

"There's a good chance that I'm gonna be killed. I'm just trying to get things sorted out for my family before that happens," Harder said.

"Somebody needs to listen to this, to look into this so police don’t do this to other people."

Both the RCMP and Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale declined interview requests, saying they don't comment on witness protection cases.

Goodale did, however, send a letter to Harder through his lawyer in Regina on May 7, warning that disclosure of "certain witness protection information" in open court could lead to five years in prison.

The RCMP ejected Harder from the WPP following numerous unspecified "breaches" of his agreement, according to documents.

Harder said some violations were minor while others were fabricated. He said the RCMP broke countless promises made to him and his family.

Specifically, Harder alleges the RCMP and the federal government:

- Failed to pay Harder the full $300,000 negotiated in exchange for four years of co-operation in Project Forseti.

- Failed to care for his business assets, home, possessions and pets, as promised.

- Left Harder and his family in "Emergency Protection" for 540 days before they were given new identities and admitted to the full Witness Protection Program. The maximum outlined under federal law is 180 days.

- Ejected him from the WPP after the Forseti prosecutions ended in May, even though he says they know he remains in danger.

"They tricked me and my family into doing something on absolutely false pretences. It seems like they can just get away with it … they screwed me," he said. Some of these allegations appear in court documents filed by Harder's lawyer in a lawsuit against the RCMP.

Other issues are detailed in transcripts Harder said he made after his negotiations with the Mounties. Still others appear to be corroborated by the texts shared with CBC News.

In one text, the federal justice official wrote Harder to say they've been told not to contact him. The official pledges to help anyway, discussing plans to track down Harder's assets being held by the RCMP in Regina.

"I haven't told police anything, except when I thought it would help you," wrote the official. "Let me know if you need me.… It is, as you know, not always easy to get answers.… I will keep at this situation," one message reads.

In another series of texts, the Saskatoon police officer blasts the RCMP and thanks Harder for his service.

"I'm sorry this is happening to you, buddy. Makes me sick … you did a great thing for Saskatoon."

In an interview, Saskatoon Police Service Supt. Dave Haye noted that the RCMP is in charge of the Witness Protection Program.

Haye said he's aware of the Saskatoon officer's texts to Harder. He said officers sometimes say things to keep a witness happy.

"It's a relationship dance."

But when asked if the officer was lying to Harder when he called the Witness Protection Program a “joke,” Haye replied, "We don't lie to witnesses."

Insiders like Harder come with a "boatload" of issues, Haye said.

But he said Harder did give them an inside look at this criminal world, took good notes and was well-prepared for court.

In a joint interview, federal Crown prosecutors Lynn Hintz and Doug Curliss noted Harder helped convict high-level drug and gun traffickers, as well as organized crime figures.

"So, yes, there is concern for his safety," Hintz said.

Saskatoon lawyer Nicholas Stooshinoff defended some of those charged in Project Forseti. He said police "were sold a bill of goods" by Harder.

Stooshinoff called Harder one of the highest level criminals in the city, referring to him a narcissist and a sociopath.

"He's always been a drug dealer. He's always been a snitch … he's always been embellishing his own image," Stooshinoff said.

II. Double life

Harder, like many WPP members, has an extensive criminal past. He grew up in Saskatoon alternating between his family home and shelters to avoid a severely abusive stepfather.

One of Harder's most vivid memories is the day his stepdad took a four-year-old Noel and his dog, Muggins, out to the railway tracks near their home. For no apparent reason, the man shot the white Cocker Spaniel and left.

"He just left me there with my dead dog. My childhood was really f--ked," he said.

Harder bounced around three different high schools but graduated in 1997. He said he avoided any criminal activity until his 20s, when his drug-dealing brother died in front of him after swallowing a condom full of heroin to avoid arrest.

Harder started using his brother's cellphone contacts to build a massive drug ring, which grossed as much as $1 million per month, according to court documents.

He was caught and sent to prison in 2004.

When Harder got out, he worked as a general labourer and eventually started his own construction firm. Harder met his wife and had two young children. Everything was going well, he said, until the Canada Revenue Agency contacted him.

Harder said he was assessed as owing $400,000 in taxes on his former drug revenues. His business bank accounts were frozen, causing his construction business to suffer. That's when he returned to drug-dealing, he said.

Harder's work as a police agent began on March 28, 2014, after he was pulled over while transporting firearms. At the time, Harder was a senior member of the Fallen Saints Motorcycle Club.

Harder's construction shop, which served as the gang's club house, was fitted with recording devices. Several times per week, Harder would sneak away to meet police in hotel rooms and get further instructions.

"They're going to take care of your needs and your safety when this is done."

In July 2014, Harder said he and his wife were interviewed as candidates for the Witness Protection Program because, at some point, they knew the investigation would end or Harder's double life would be discovered.

Harder and the RCMP began an extensive series of negotiations.

Harder said he was not allowed to record these negotiations and was searched before each meeting. He was eventually given one chance to hear and transcribe the recordings made by the RCMP, he said.

He provided those transcripts to CBC News.

"They [RCMP bosses] are absolutely excited about tackling organized crime in the city to an extent that it's never been tackled before," a RCMP negotiator told Harder, according to the transcript.

"They're going to take care of your needs and your safety when this is done."

They discussed Harder's multiple business assets, and how to find a school and doctor for Harder's children.

"No one's going to leave you high and dry," the officer said.

Harder asked for protection and new identities for him and his family — and then for $1 million for his full co-operation in the investigation and prosecutions.

The officer said his bosses would ridicule a request of that size.

They settled on roughly $500,000: a direct payment of $300,000, plus allowances to cover Harder's business and personal expenses.

"We're quite prepared to pay that figure all right," the officer said. "We're not out to try and screw anybody."

The officer closed the meeting by saying it was being recorded.

III. Emergency protection

Believing the negotiations were settled, Harder said he continued to secretly collect evidence for police.

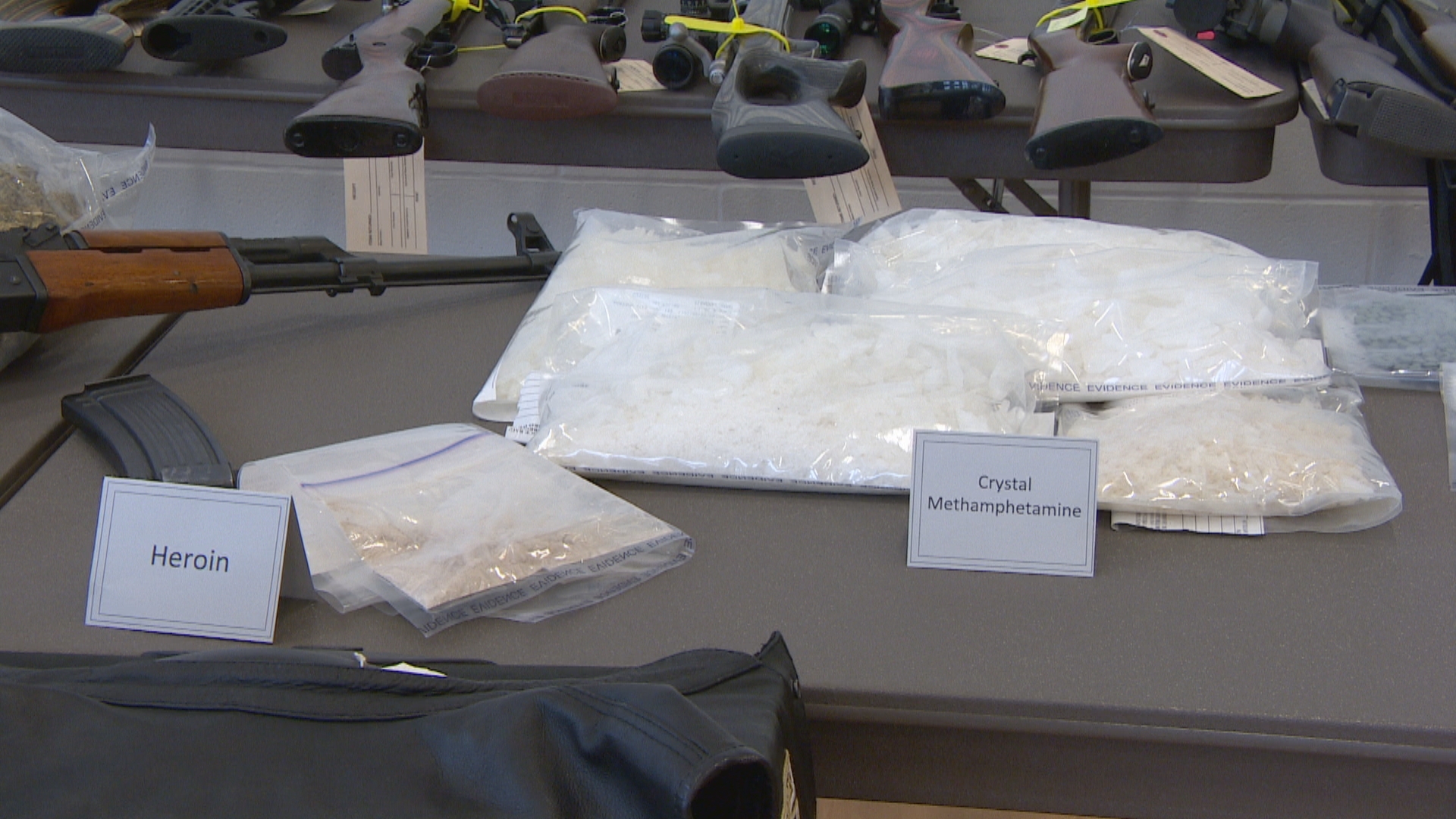

That ended on Jan. 14, 2014, when the joint RCMP-Saskatoon police operation raided 19 locations in seven cities. An estimated $8 million worth of methamphetamine, cocaine and fentanyl linked to at least three Saskatoon overdose deaths was seized.

More than a dozen members of the Fallen Saints, Hells Angels and other organizations were charged with a variety of offences.

Just before the raids, Harder and his family were taken to another province by the RCMP.

Harder believed they'd be placed directly in the Witness Protection Program, but said they were instead given the lesser "emergency protection" status and told they’d be evaluated.

They weren't given new identities, he said, which meant they couldn't find a job, use the internet, apply for a credit card, enroll their kids in school or check out a library book — at least not without risk of being found.

"I would have never become an agent had I known."

RCMP are only allowed to keep people in emergency protection for a maximum of 180 days. According to the lawsuit documents, Harder and his family were left in this "limbo" for 540 days. They were shuttled among five provinces by 15 different RCMP "handlers."

"I would have never become an agent had I known," Harder said.

During this time, Harder says RCMP broke promises to sell or maintain his vehicles and other property.

He said some instalments of the $300,000 came, but others did not. The RCMP would say they paid off his tax bills or extra business expenses, he said, but did not show him receipts.

The RCMP also promised to care for the family's menagerie of pets. An English bulldog named Charlie and a cat named Peaches were returned to them. Two other cats, a canary, a guinea pig, and an iguana were found by a relative at the SPCA, he said.

Throughout this period, Harder was flown to Saskatoon and other cities to testify under armed guard in the Forseti prosecutions.

In May 2016, the RCMP told Harder and his wife they'd be admitted to the WPP. They were given new identities and settled into a new home. Life seemed good again, he said. Harder got a job. The kids were starting to make friends.

That ended in the fall of 2017. Harder said he was spotted in public by a group of bikers who recognized his face.

One biker pressed him against a wall and said the Hells Angels had offered a bounty on Harder's head. Sources told CBC News the bounty was at one time $200,000 but has since risen to $2 million. Harder convinced the men he had a gun and fled.

He and his wife knew their time in that town was over, but Harder said it was another three tense weeks before they were moved to another temporary shelter.

Over the past several months, the Forseti investigations drew to a close. All but one of the people targeted were convicted.

That target, Clint McLaughlin, was released to a halfway house last week as part of a separate six-year sentence for kidnapping and torturing his girlfriend. He has been declared a high risk to reoffend.

IV. The goodbye

Harder said the RCMP made various excuses why they couldn't resettle his family again.

In March 2018, Harder filed a lawsuit against the federal government in Regina's Court of Queen's Bench. He said he was trying to keep his family safe, get paid for his work and expose the flaws in the WPP.

None of the allegations have been proven in court.

Lawsuit defendants typically have 30 days to submit a written response in court, but none has yet been filed.

Shortly after the lawsuit was filed, Harder said he was cited for several "breaches" of the program. He admits to two instances of cocaine use in the three years, but disputed others. (He admits the drug use was wrong, but not serious enough to eject him from the program.)

"People need to know what's happening. ... This is about holding the RCMP accountable."

Harder said he was cited for things such as failing to immediately answer the door for the RCMP.

Every breach, he said, was filed by the same RCMP officer.

Harder has been on his own since May 3, when he said a tearful goodbye to his wife and kids. His family remains in witness protection and were shuttled to another secret location.

"I'm sorry, I'm sorry. I love you," Harder recalls telling his crying 12-year-old daughter and 10-year old son. "Be strong for Mom. I'm gonna fix this."

Harder said the RCMP has threatened to kick them out of the WPP too if he doesn’t give up on the lawsuit.

"People need to know what's happening. This isn't about sympathy for me or my lawsuit. This is about holding the RCMP accountable."

V. The program

Experts across Canada are critical of the Witness Protection Program.

A federal advisory committee report released in January says the program is improving but remains plagued by a host of problems.

Its total national budget — pegged at $9 million for the most recent year — is inadequate, said the report. Officers are overworked and witness safety has been unnecessarily compromised by investigators, it said.

Witnesses are told to report complaints to their designated RCMP officer, who may be the source of the problem, it said. If witnesses try to file complaints to the independent, civilian Public Complaints Commission, RCMP can refuse to disclose information.

But the report reserved its harshest criticism for the program's record-keeping.

"The committee deplores the fact that the program is still experiencing difficulties in ensuring that data on every protectee is adequately captured on the information management system," it reads.

Committee member and University of Ottawa criminology professor Irvin Waller said despite the improvements, he finds the lack of data troubling.

"Police can't make a dent in organized crime without a snitch. You need a snitch."

The program can't learn from its mistakes, he said, if no one keeps proper records.

"I saw them as being on a learning curve," Waller said.

Waller declined to discuss Harder’s case, but said it's vital for RCMP members to keep their promises.

"It's a life and death issue. You're protecting a witness from people who won't hesitate to kill them."

Simon Fraser University criminology professor Rick Parent said the ethics of witness protection are often "thorny."

"We're not talking about normal people," he said.

But Parent, Waller and others say these insiders can be essential to some cases, particularly those involving terrorism or organized crime. Without their information, police couldn't lay charges. Without their testimony, prosecutors couldn't get a conviction.

In some Forseti prosecutions, judges questioned Harder's motive or credibility. In others, court officials said there would have been no conviction without Harder's testimony.

"Police can't make a dent in organized crime without a snitch. You need a snitch," said organized crime expert Yves Lavigne.

"Snitches go back to the end of time. I'm sure the word snitch exists in another way in the Bible. So without this informant, or this agent, as he became, they would not have done anything in Saskatchewan."

Lavigne said has no sympathy for witnesses who break the rules; but he said the RCMP — and all Canadians — should be grateful for their efforts.

"They've sacrificed their entire lives to provide information to put criminals behind bars. If the cops don't respect that behaviour, no one else is going to want to work for them or become agents for them," said Lavigne, who conducts seminars on organized crime for Canadian police forces.

RCMP spokesperson Harold Pfleiderer said in an email that the Witness Protection Program aims to be transparent.

He declined to discuss Harder's case, but said any decision to eject someone from the program is approved by the RCMP commissioner.

Witnesses who don't follow the rules can endanger themselves, their families and the officers protecting them, Pfleiderer said.

VI. Hiding unprotected

Harder disputes he was a danger to anyone; he believes he simply wasn't useful to police after Forseti wrapped up.

As for the criticism about the program's poor records or lack of oversight, Harder suspects federal officials intentionally "drag their feet" on potential fixes because it would reveal a host of other broken promises.

"This whole thing is a joke, just a disaster," Harder said.

He said he dreams of leaving everything behind, resettling with his wife and kids on a faraway tropical beach.

Until then, he remains in hiding without police protection, though he's taken up his own security measures, like sleeping for short periods at unpredictable times to stay on guard.

"If somebody was coming to kill me," Harder said, "I’m going to be taking them with me, if not first."