Doreen Nowicki did not want to die this way. During the ride to a respite room, arranged for her death, she sobbed: Unrelenting wails of anguish that shook her chest and reverberated throughout the back of the ambulance.

Strength had long since slipped from Nowicki's body; the ability to walk, raise her arms, swallow without effort. Even speak.

So it fell to one of her daughters, Cathy, to gently wipe her tear-streaked face and readjust the glasses that kept sliding down her nose. The ambulance trip took half an hour. Nowicki's husband of 44 years, Terry, held her hand.

Doreen Nowicki wanted to die. But not like this, transported to a facility she didn't know, to draw her last breaths in a room that wasn't hers.

It was the worst indignity in a series of indignities Nowicki was forced to endure in the final weeks of her life, as she pursued a medically assisted death.

Nowicki suffered these indignities because of where she had been a patient when she first sought help to end her life: a continuing care centre operated by Alberta's Catholic health-care provider, Covenant Health.

"It was incredibly horrible to go through this," said Kim Pelletier, one of Nowicki’s three daughters who lived through the experience with their mother.

"To be put in a situation where you feel your loved one is not treated fairly and, in fact, is treated unjustly and inhumanely at their most vulnerable stages of life."

Nowicki's death — and her last few weeks of life — illustrate how the religious beliefs of a Catholic health-care provider resulted in a policy that can effectively override a palliative patient's right to a dignified and humane death.

Covenant Health's policy on medical assistance in dying (MAID) is not unique. Like many Catholic health-care providers across Canada, the publicly funded organization refuses to facilitate MAID procedures, citing ethical and moral objections that make participating in such an act unconscionable.

The Alberta government, which controls how MAID is administered in the province, has exempted Covenant Health from having to do so.

But Covenant Health cannot obstruct a patient's right to seek a procedure that the federal government legalized more than two years ago. It must give patients who request MAID access to resources available through the province's health authority, Alberta Health Services (AHS).

Except in limited circumstances, Covenant Health requires its patients to be transferred from its facilities for the assessments required to determine if they meet the legal requirements for a medically assisted death. Patients are always transferred for the procedure itself.

That is the organization’s position on paper. Nowicki’s daughters have lived the messy reality it creates; in the hospital room that became their mother’s home, in the ambulance in which she rode to her death.

They have navigated an ambiguous policy that allows Covenant Health to unilaterally approve — or deny — MAID requests from patients, even those as frail as Nowicki, who wish to have their eligibility assessed without leaving their Covenant Health beds.

They have watched their mother die in an unfamiliar place.

"This is not how we should be treating people in their end-stages of life," Cathy Nowicki said. "Like, 'Oh, you have made this decision but now you have to go somewhere else to end your life because your decision isn't OK with us.'

"I don't know why anyone gets to make that decision."

Loss of function, loss of dignity

Doreen Nowicki was 65 in the fall of 2015, when she suddenly developed a limp.

Her family watched, concerned, as her gait became slower and uneven. One night, on their way to a concert, Cathy Nowicki noticed her mother couldn't keep pace as they walked from the parkade to the venue.

The impaired mobility frustrated a woman who was constantly in motion.

When Nowicki's daughters describe her, they nearly always mention the energy she expended bestowing kindness on others: shopping trips that invariably resulted in far more gifts for her children and grandchildren than for herself; plans to bake coffee cake that soon became plans to make a dozen cakes to distribute to family and friends; a greeting card painstakingly chosen for a loved one's special occasion.

She kept so busy that she could run through a day without realizing she hadn't eaten. When she finally did slow down, like at the movie theatre, she would fall asleep during the trailers.

Nowicki thought her hip might be the problem, but her entire left side was weak. Doctors thought she may have suffered a stroke.

"And then she just kind of started falling," said Michele Emmanuel, Nowicki's eldest daughter.

Nowicki eventually received a tentative diagnosis of primary lateral sclerosis, a motor neuron disease that is a sister to the more well-known ALS. Her family has since learned that Nowicki actually had ALS.

Her condition deteriorated rapidly. In February 2017, Nowicki was transferred to a restorative care bed at the Edmonton General Continuing Care Centre, a Covenant Health facility.

Her daughters said they had no choice in where she went; they agreed because that is where a bed was available.

Doreen Nowicki, who loved to shop and travel, could no longer safely walk unassisted. The independent mother, who insisted on Sunday family dinners, could now only eat soft, easy-to-swallow foods.

Within a few months, Nowicki needed a mechanical lift to get out of her hospital bed.

"She needed someone to do all her care for her — to dress her, to toilet her, to feed her," Cathy Nowicki said. "And that loss of dignity, for her, was too much."

A decision to die

Covenant Health is a massive operation. The religiously affiliated organization oversees a budget of about $850 million — the vast majority supplied by the province — and operates 17 hospitals and care centres across Alberta. It has one of the largest budgets of Catholic health-care providers in Canada.

In some of Alberta's rural communities, like Camrose, the only nearby hospital is a Covenant Health facility. The organization controls more than one-third of the province's palliative care beds.

By May 2017, Nowicki occupied one of those palliative beds.

She had come to accept that her health would never improve. Now she wanted to die on her own terms.

"I think it was finally that awareness that she didn't have much longer and she had nearly lost all functions," said Pelletier. "And she was just suffering so badly that there was no hope."

Because Covenant Health refuses to provide medical assistance in dying, patients like Nowicki are forced to deal with an additional bureaucratic challenge.

After meeting with Covenant staff to discuss their options, if a patient still wants to pursue MAID, they must contact a specialized team at AHS. Although, if asked, Covenant staff will contact that team directly for the patient.

That is where Covenant wants its involvement with MAID requests to end. Its default policy position is that patients cannot fill out a MAID request form, or be assessed for eligibility, on Covenant Health property.

So what happens if a patient is too sick to be safely transferred off-site in order to access the MAID process?

At the time of Nowicki's request, Covenant Health's policy didn't specify how it would deal with such a situation, although documents obtained through freedom of information show the organization sometimes permitted on-site form signings, as well as some assessments by AHS staff.

The decision-making authority rested with Gordon Self, Covenant's chief ethics officer, and Dr. Owen Heisler, its chief medical officer.

Nowicki was granted an exception.

"I have been in contact with the Covenant administration, and have received permission for your mother to sign the record of request on-site, as well as have the independent assessments on-site," an AHS MAID navigator wrote to Emmanuel on May 11, 2017.

The first assessment was scheduled for two weeks later.

On the morning of the assessment, Emmanuel was on her way to the Edmonton General to meet with her mother and two sisters when her phone rang.

It was the AHS nurse practitioner who would be assessing Nowicki. He sounded upset.

"He said, 'I just received a phone call. We are no longer allowed to provide the assessment on Covenant property. Not at the General, not in the parking lot, not even on the property.'"

The assessment was scheduled to take place in a little over an hour.

Nowicki lay in her bed, oblivious. No one had told her, other family members, or the Covenant front-line staff caring for her of the reversal.

Emmanuel quickly contacted her sisters.

"It was chaos," Pelletier recalled. "It was just panic to figure out how we could proceed with carrying out her wishes in terms of having this discussion and having this assessment done."

Cathy Nowicki and the nursing staff quickly dressed Nowicki, then used the mechanical lift to get her out of bed, before tucking her feeble body into a wheelchair. She didn't understand what was happening.

"She got very panicky, she got very shaky," Pelletier said.

Nowicki cried as her daughters pushed her out of the facility and onto the street to meet the nurse practitioner.

"Why on street?" Nowicki, unable to speak, scrawled on her tablet with her one functioning hand. "Why?" she wrote over and over. "Why? Why?"

Nobody could answer.

Then came an angry message from a woman who rarely swore.

"This is bullshit," she wrote.

The AHS assessor, also blindsided by the sudden change, scrambled to arrange a private room for the assessment at a nearby seniors centre. The centre agreed, but the room wasn't immediately available.

So one of the most important and sensitive discussions of Doreen Nowicki's life — about how, with medical help, she intended to end it — began, with Nowicki in a wheelchair, bundled against a cool May wind, straining to hear the assessor, and her three daughters seated on street benches, near busy Jasper Avenue, as traffic whizzed by and as strangers walked past.

"It made no sense to us why my mom would be treated so inhumanely," Emmanuel said.

"Almost like being punished for making her decision. That is how we felt."

'Made to feel like criminals'

A half-hour later, the family finally gained access to the private room. But by then, Nowicki was too distracted and emotionally spent for the assessment to continue.

"It was kind of doomed from the beginning because she was so distraught about what was happening," Cathy Nowicki said. "And not understanding, and not focused on anything but, 'Why am I out of the building? Why am I out of my room? What is going on?'"

More than a year later, the sisters are still angry about how Covenant Health treated their mother.

"We were made to feel like criminals," Pelletier said. "Why could we not have a conversation or an assessment that she had a legal right to have in a health-care facility that is publicly funded? I don't understand that."

The family eventually learned — second-hand, from one of their mother's doctors — that Covenant management believed Nowicki should be able to have the assessment off-site because she was occasionally able to return home on day passes.

Nowicki's family argues that this was a challenging process that required securing a vehicle with wheelchair accessibility.

"It was very difficult to get my mother home on pass," said Emmanuel, a registered nurse. "But we just plowed through to try to make her remaining days as good as we could for her."

Documents obtained through freedom of information offer little clarity about why Covenant Health abruptly rescinded permission for the on-site assessment.

In an email exchange with Dr. James Silvius, AHS's head of MAID, Covenant's chief ethics officer appeared to attribute the incident to a miscommunication among senior management.

"It is truly regrettable that the family in this case were impacted by the reversal of the decision to allow on-site assessments," Gordon Self said in an email a few weeks after the incident.

"I take responsibility for the harm this caused the family," Self said, adding that Covenant would be looking at "corrective actions going forward to ensure all the right people are connected at the Covenant site level when urgent decisions need to be made."

His email made no mention of its impact on Nowicki herself.

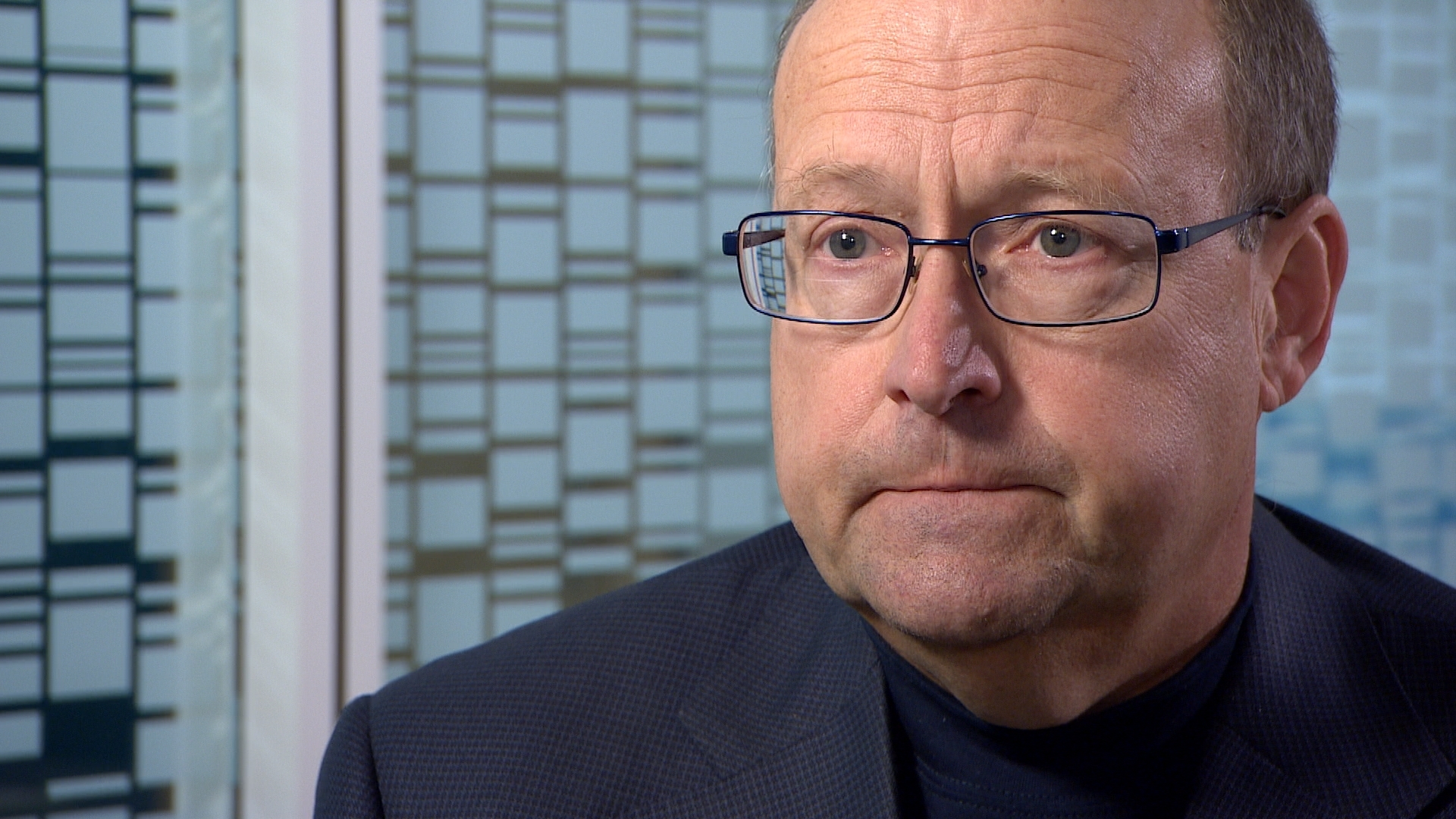

Covenant Health's chief medical officer, Dr. Owen Heisler, admits the organization failed Nowicki, but he refused to reveal who made the decision to abruptly revoke permission for the on-site assessment and why.

"We didn't treat the patient well. We didn't treat the family well," Heisler said in an interview with CBC News.

"And for that, we feel very sorry for the family to have to go through this, and particularly the patient."

Heisler said Covenant Health has improved its communication to ensure this doesn't happen again, although he also admitted the organization doesn't track how many patients are forced to be transferred from Covenant facilities for their assessments.

The family said no one from Covenant Health management, nor the provincial government, ever reached out to Nowicki or her family to explain why the on-site assessment approval was rescinded — or to apologize.

"For an organization that is focused on caring and compassion, I didn’t get any of that in return after the situation," Pelletier said.

She and her sisters said they chose not to file a complaint with Covenant Health patient relations. They were livid, but also focused on helping their mother get the assisted death she wanted.

A 'cruel' policy

One of Nowicki's doctors was angry too. Months after the incident, his written complaint wended its way through the provincial government, moving from an MLA, to the office of the minister of health, to AHS's head of medical assistance in dying.

Without naming Doreen Nowicki, the doctor described what happened on the day of her assessment and the devastating impact the last-minute change had on Nowicki and her family.

"This is cruel," he wrote of Covenant Health's insistence that MAID assessments be done off-site. "It adds to stress, both for patients and their families, and causes needless suffering.

"Please note that I am talking about talking about MAID, not providing it," he continued.

"Legislation protects individuals' right to opt out of MAID on ethical grounds; it does not allow individuals, or institutions, to undermine a patient's access to MAID," the doctor said, imploring the provincial government to address Covenant's policy.

Internal AHS documents don't reveal what happened to the doctor's complaint.

A few months after Nowicki's curbside assessment, Covenant clarified its MAID policy. The policy now states Covenant "might" allow MAID assessments at their sites if a patient is "extremely medically fragile" and is unable to stop treatment, or be transferred, without risk of harm. But that is for Covenant Health to determine.

The policy is not set to be reviewed again until September 2020.

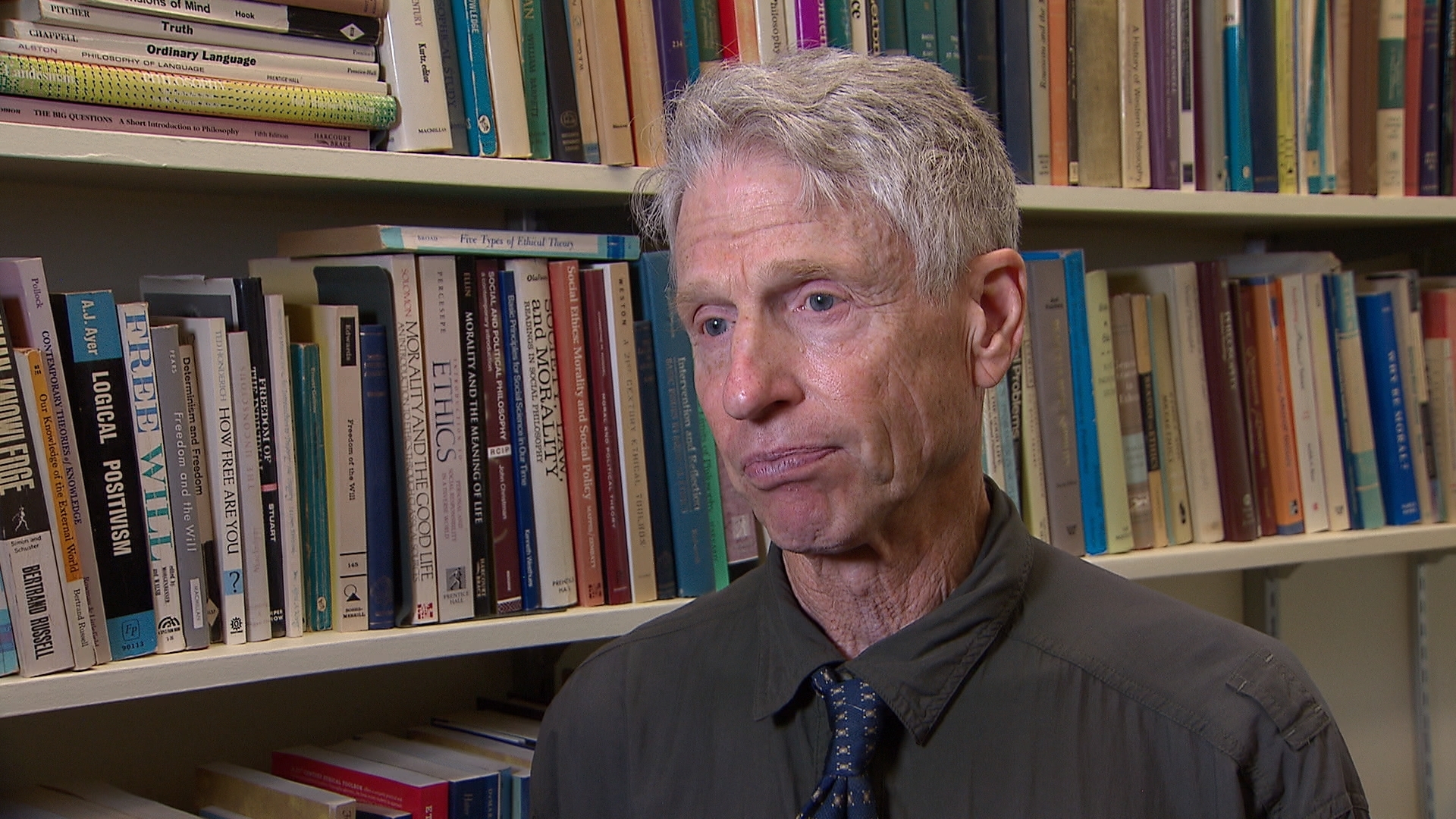

University of Manitoba ethics professor Arthur Schafer said Covenant's position — and the provincial government's tolerance of it — are both ethically indefensible.

"We are talking about a fundamental human right, not a privilege to be bestowed at the discretion of a Catholic or religious bureaucrat," said Schafer, who sat on the Provincial-Territorial Expert Advisory Group on Physician-Assisted Dying.

He called Covenant Health's treatment of Nowicki "cruel and inhumane," and an example of why provincial governments must mandate that all health-care institutions allow MAID within their walls.

"The idea that patients will be denied their rights and will be forced, when they are most frail and vulnerable, into the indignity and the distress of having to move in order to receive a procedure to which every Canadian is legally entitled, seems unacceptable."

Schafer added that if the public is distressed by what happened to Nowicki, like the doctor who treated her, they should consider writing to their MLA, premier, or ministers of health "to insist that publicly funded hospitals, nursing homes and palliative care wards should all provide patients with the full range of options at the end of life."

Finally at peace

Nowicki didn't let the stress of the botched assessment deter her. She soon received her two required assessments. Both clearly established that her condition qualified her for a medically assisted death.

The procedure was scheduled for June 5, 2017.

Nowicki counted down the days.

"That sounds weird, but she had just declined so much," Emmanuel said. "She would write on her tablet to us, 'One more shower,' or 'One more this,' and 'One more that.'

"And we were just like, 'Mom! Come on!'" she said, laughing at the memory. "But she was just at peace with her decision and couldn't wait."

The day of the procedure, Emmanuel and her family entered Nowicki's room at the Edmonton General for the last time.

They brought her Nutella banana crepes from IHOP, her favourite breakfast. Nowicki couldn't savour the food; a few days earlier, she had lost her sense of taste. She ate it anyway, choking so hard at one point that her face turned blue and her family thought she might die right there.

They then packed up her belongings and brought her home. Relatives spent the day at the house, saying their final goodbyes.

Nowicki didn't want to die at home; her family thinks she didn't want the memory of her death to linger there.

So shortly before 6 p.m., the doorbell rang. It was the paramedics, who had come to transport her to CapitalCare Norwood, an AHS long-term care centre.

"That was extremely, extremely hard," Pelletier said. "I think she would have just been a lot more settled and at peace if she could have just stayed in her hospital room [at Edmonton General] where she had been living the last several weeks prior."

Nowicki's family huddled around her bed in a respite room at the long-term care centre. Emmanuel's husband read Nowicki a letter he had written for her. Then family members took turns hugging Nowicki and telling her how much they loved her — until it was time.

Nowicki motioned to her husband Terry: A final kiss please.

Then she waved the nurse practitioner over. The injections were made ready.

Her funeral was just as she wanted it; she had already picked out her dress, her jewelry, the hymns that would play at the church.

"My mom's handprints were all over it," Pelletier said. "It was incredibly sad, but also incredibly beautiful, that she was able to be with us and do that."

Nowicki's daughters take comfort in knowing that their mother's death was peaceful. But what will also stay with them forever is how an intrinsically cruel policy traumatized Nowicki in the final weeks of her life.

"I just want a better system," Pelletier said, explaining why she agreed to share her mother's story. "I don't want this to happen to anyone else."

"It shouldn't matter if some random higher-up thinks that, 'No, these are not our values,'" Cathy Nowicki said. "Isn't a person — a human being — having compassionate care a value we need to respect?

"She was a human being at the end of this. And there were some times during this process where we feel she wasn't treated like a human being."

If someone you know has had a similar experience, or you have information about this story, please contact us in confidence at cbcinvestigates@cbc.ca.