October 8, 2018

For decades, the fate of their grandfathers was a mystery.

They were victims of what's known as the Great Purge, some of the more than 9,000 German Mennonites arrested in Ukraine from 1936-38, during Soviet leader Joseph Stalin's ethnically motivated persecution.

Scooped up in the middle of the night by the Russian NKVD, the predecessor of the Soviet KGB, the men were arrested on the pretence of treason and never heard from again.

Their families fled to countries like Canada to begin new lives. But they have always wondered what happened.

This summer, some of them travelled to Ukraine on a Mennonite Heritage Cruise organized by historians Walter and Marina Unger of Toronto.

Three families gained access to recently opened KGB archives. Two shared with the CBC what they learned — and how it felt to get answers to questions their families have lived with for generations.

Questions without answers

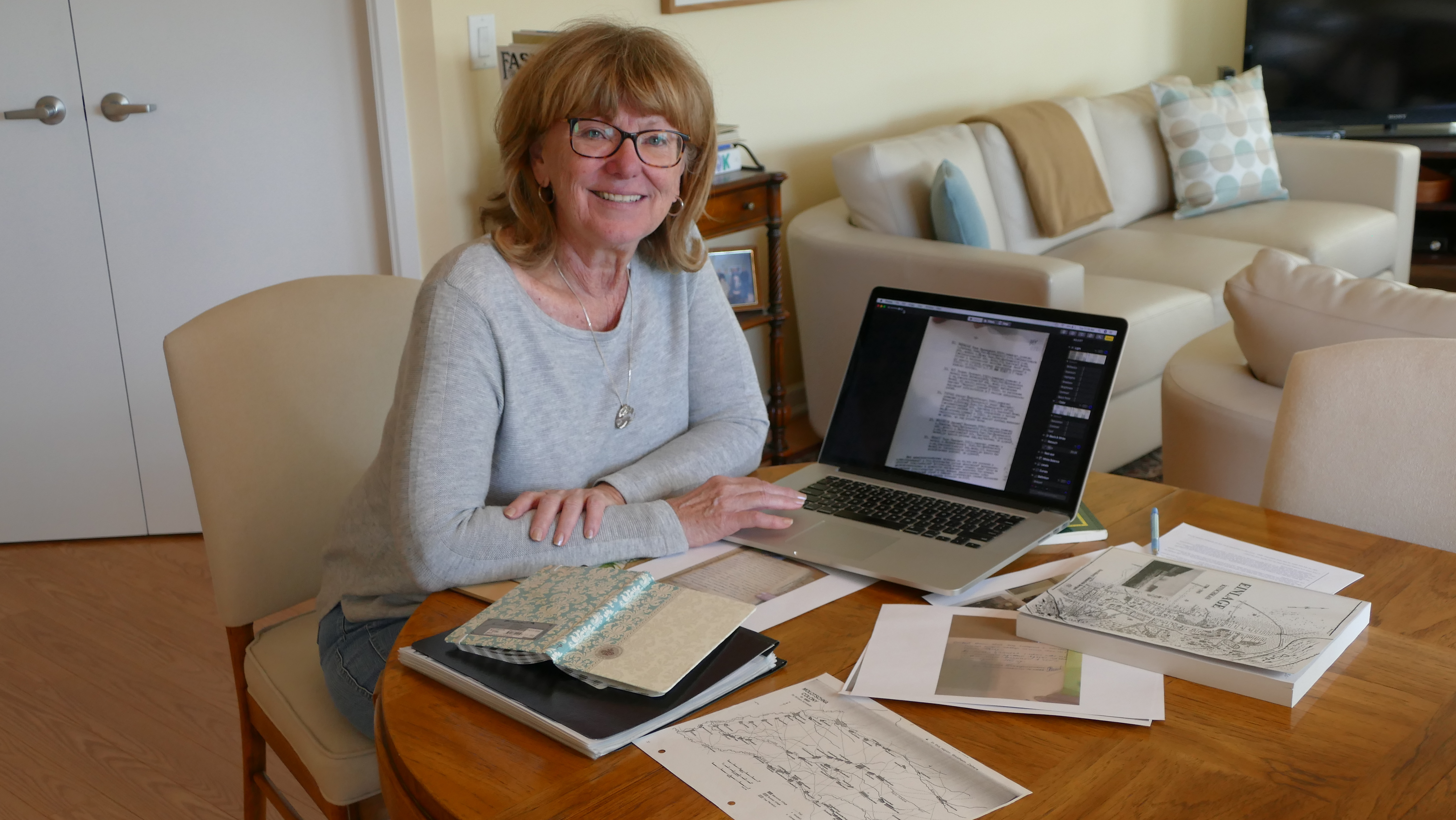

Winnipegger Erna Braun, 67, knew from a young age that her opa (grandfather) Johann Johann Braun was taken by the Soviets.

The arrest deeply affected her father, Johann Braun.

But it wasn't until Erna Braun was first elected vice-president of the Winnipeg Teachers' Association in 1989 that she understood how much the arrest and loss of her grandfather had affected her father.

"One evening as I had dinner with my parents, my father said to me that I was just like my grandfather. That was the first indication I had that my opa had been a community leader, and that was the reason, according to my dad, why my opa had been taken," Braun said.

"He felt strongly that if you put yourself out there, there would be negative consequences. When I was approached in 1999 to run for the NDP provincially, he was so upset."

(Braun turned down the first two requests to run for the NDP, but accepted the third time. She was elected and served as minister of labour and immigration for Manitoba until 2016.)

Braun's grandmother wrote to authorities in 1957 asking for information about her husband. She was told he died of heart disease in 1945 while in detention.

At the time, he was sentenced to be shot. His name was listed in the KGB dossiers along with a dozen other men who were executed.

That seemed to be the most Braun would ever know about her grandfather's last days — until earlier this year.

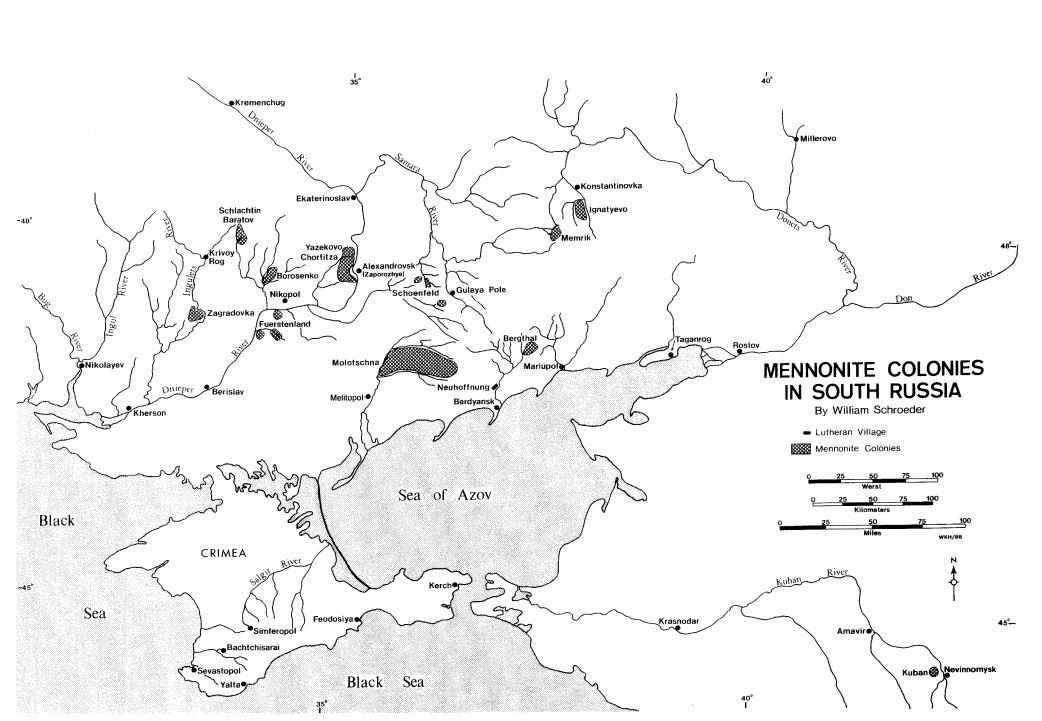

Braun signed up to go on the Mennonite Heritage Cruise on the Dnieper River this past summer. She visited the old homesteads and settlements developed by Dutch and German Mennonites who had been invited by Catherine the Great in the late 1780s to develop and industrialize the area around Zaporozhye, Ukraine.

Braun submitted a request to view any documentation the cruise historians could find on her grandfather.

'There is an urgency'

The KGB archives in Russia were briefly opened to direct relatives in 1989, but they were sealed again just a couple of years later.

Earlier this year, the Ukrainian government opened its KGB archives to scholars for the first time.

"Right now it seems like they're open and that's great, but you never know in this system, so yes, there is an urgency to the KGB archives,” said Aileen Friesen, co-director of the Centre for Transnational Mennonite Studies at the University of Winnipeg.

“It's open, let's go in there and try to find as much information as possible."

There is also an urgency because those with direct memories or connections to this story are getting older.

"If we don't preserve that history, if we don't tell that story, it becomes very difficult for the subsequent generations to feel they actually have a connection to this place that has meant so much in our history," Friesen said.

Detailed dossiers

The dossiers contain a mugshot of each arrested person. They include documents that list charges, a transcript of the interrogation, and information about where the person was executed and buried. They might also include the identity of an accuser.

Soon after her request, the historians who organized the trip told Braun a file had been located.

"I was stunned,” she said. “I could not believe that his file was there. After growing up with stories about life in Ukraine and the challenges, I was overcome with emotion with the thought that I would see the actual evidence of my opa's life.”

Many of the cruise participants applied for similar information about their ancestors, but files were found for only two other families.

"This was one of the most important journeys of my life," Bernie Neufeld wrote in an email interview from Sydney, Australia.

He and two of his brothers are originally from Winnipeg, where their five sisters still live. Their mission was to discover the fate of their grandfather Abram Kroeger, who disappeared in the late 1930s.

"I have wanted to know what happened to my grandfather all my life,” Neufeld said. “I heard he had disappeared. My mother and grandmother always talked about it. We could see how profoundly it affected them.”

Stepping back in time

The cruise ship docked in Zaporozhye, Ukraine, for five days. On July 28, the three families were taken to the state archives, where their relatives' files had been moved.

The government office building was set up like a classroom with desks and chairs. Bookshelves and filing cabinets lined the walls.

The families were greeted by the supervisor and three female translators.

Braun was guided to two well-worn binders on a desk.

One contained handwritten notes of Braun's grandfather's interrogation. He was charged with anti-Soviet activities in German colonies and recruiting others to join in those activities.

"My translator had had a chance to review the file in advance and had even made some notes for herself to help during our session," Braun says.

The interpreters walked them through each page. The details gave Braun goosebumps.

On Feb. 20, 1938, Johann Johann Braun was interrogated about his activities in 1918 and 1919.

The notes say he was working on a farm when it was attacked. He tried to protect it, but fled when he realized he would be captured.

He joined the White Army, which was fighting the Communist Bolsheviks (known as the Red Army) in the Russian Civil War. When the anti-Communist forces were defeated, he returned home, although small factions of the defeated Whites continued operating underground until around the Second World War.

"The interrogator kept asking about his counter-revolutionary activities, but my grandfather kept insisting that after his stint in the White Army, he had not been involved in any,” Braun said.

“The interrogator responded that they had information that he had been. My grandfather requested the names of his accusers. That statement was not recognized.

"After each entry, my grandfather had to add his signature."

Braun’s grandfather was questioned again on Feb. 28, 1938.

"'You insist on hiding facts from interrogators. Tell the truth,'" Braun read from notes she took of the translated files.

In them, her grandfather replied: "'I told the truth about my activities in the German community in which I lived.’”

At the end of the session, he pleaded guilty to counter-revolutionary activity and being a member of a rebel group.

All of the men questioned during that time were sentenced to be shot to death, and all their property was appropriated.

"Hearing all the details of his interrogation was very emotional," Braun said.

"I kept thinking of those eight days between interrogations, what he had been put through to exact the responses he gave and then to sign a confession. I couldn't help but imagine the fear he felt of never seeing his family again.

"It still makes me teary."

Johann Johann Braun was exonerated in 1989, part of Mikhail Gorbachev's period of glasnost (openness).

"Part of me feels a sense of closure on the one aspect of my dad's family history that we didn't know, but on the other hand, I now have a picture of the terror that he and the others all experienced. That part is difficult," Braun says.

"It was concrete evidence, no longer stories but concrete facts I got to see."

'Determination to seek justice'

Across the room from Braun, Bernie Neufeld, 71, and his brothers were also taking notes as translators sifted through their grandfather's file.

Abram Kroeger was 46 when he was arrested. He left behind a wife and five children.

Neufeld saw a list of the children's names. It includes his mother, who was then 17.

His grandfather was a farmer before and after the revolution and worked as a harness maker on a collective farm. He had no previous criminal record.

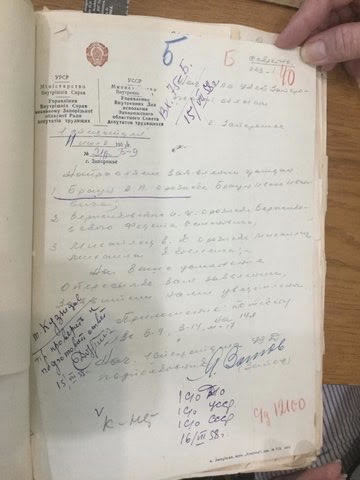

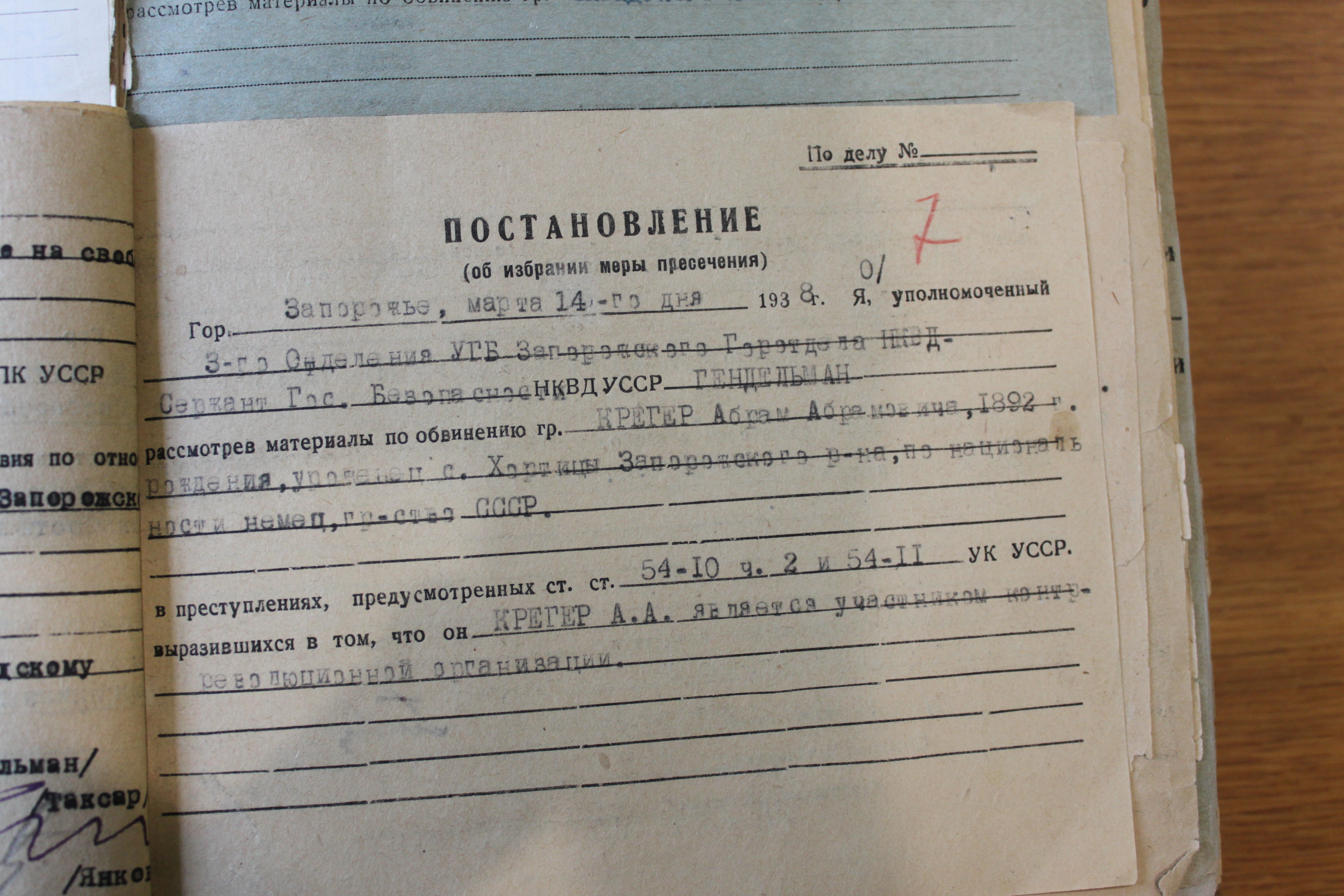

"The arrest warrant, issued by a representative of the NKVD, states that Abram Kroeger … is accused of being a participant in a counter-revolutionary organization," Neufeld wrote.

"On March 14, 1938, without any supporting evidence, and based only on accusations, the prosecutor authorized the NKVD to arrest him until the end of the investigation and trial under Article 143 of the Criminal Code."

The trial was based on an accusation by Dietrich Regehr, who provided the NKVD with a list of people he said were active in a German-controlled revolutionary organization set up to subvert Soviet control.

Neufeld believes Regehr made a plea bargain in exchange for his freedom.

The files say Abram Kroeger admitted to being part of a German terrorist organization that blew up a bridge, destroyed roads and deliberately damaged equipment to slow Soviet progress in the war.

"The files show his signature, admitting to these charges. His admission was likely under duress and torture," Neufeld wrote.

All the men accused by Regehr were found guilty by the Troika War Council, which had the right to execute people without evidence.

Abram Kroeger was executed by shooting on Nov. 14, 1938, and all his property confiscated.

He too was exonerated in 1989.

"Learning that my grandfather was executed, and then exonerated 51 years later, was heartbreaking. It brought tears to my eyes," Neufeld said.

"I felt anger. But I also felt relief to finally have the truth. I am grateful that the government of Ukraine made these files available, that they had the courage to exonerate my grandfather."

Neufeld also got to see the file of Dietrich Epp, his grandmother's brother.

Epp was convicted of similar crimes with no evidence. He was executed and his property was confiscated. He was also exonerated 51 years after his death.

Neufeld continues to search for files of five other missing members of his extended family.

"It brings a sense of closure, a sense of power and a determination to seek justice," he said.

"I want the Russian government, the architect of the institutions that committed those crimes, to be held accountable, to apologize, to pay compensation to their victims and to change their behaviour.”

Aileen Friesen was on the Mennonite Heritage Cruise this summer as the in-house historian.

The pilgrimage was emotional for those who got files — and also for those who didn't, she said.

"There were people who couldn't find their family members and it's a very emotional situation because they want closure to this period in their lives, but they can't have it," she said. "How do you let go of something you don't know?"

Through a newly created Paul Toews Fellowship in Russian Mennonite History, Friesen and others will record, translate and archive as many files as they can access through the KGB archives and from families who donate copies of the documents they've received.

Friesen will also study how the individual stories fit into the larger historical picture — how the Mennonites survived the Holodomor, the man-made famine in Soviet Ukraine in 1932-33, and then faced the breakdown of their own tight-knit communities during the Great Purge.

"These files close some wounds but open up new ones,” Friesen said.

“The new ones they open up is that typically, these people have been betrayed by someone. That's how their name gets on the list. They've been betrayed.”

"It's easy to think of this as a black-and-white scenario — this person is bad because he or she gave up my relative — but the reality is either that person was tortured [or] that person's family was threatened. The idea of choice within the Soviet system is a very nebulous concept."

Friesen says this is not just ancient history — it also has implications for today.

If scholars can contextualize and tell the broader story, it can provide insight into how totalitarian states are influencing people's lives right now — and what the repercussions might be for subsequent generations.

Cover photo: The arrest photo of Jacob Reimer, a victim of Stalin's Great Purge. The mysteries surrounding his identity, and what his family was told about him, are detailed in a book called It Happened in Moscow: A Memoir of Discovery by Maureen Klassen. (Submitted by Centre for Mennonite Brethren Studies)