January 18, 2021

Casual use of the N-word. Physical assaults. A stuffed animal painted black and hanged from a noose at a firehall where a Black firefighter worked. Two workplace reviews the city keeps so secret, it has denied one's very existence and redacted every word in the other when forced by law to turn it over.

These are just some of the experiences detailed by a group of current and former BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of colour) employees at the Calgary Fire Department (CFD) who are demanding nine changes to what they describe as an "extremely toxic environment."

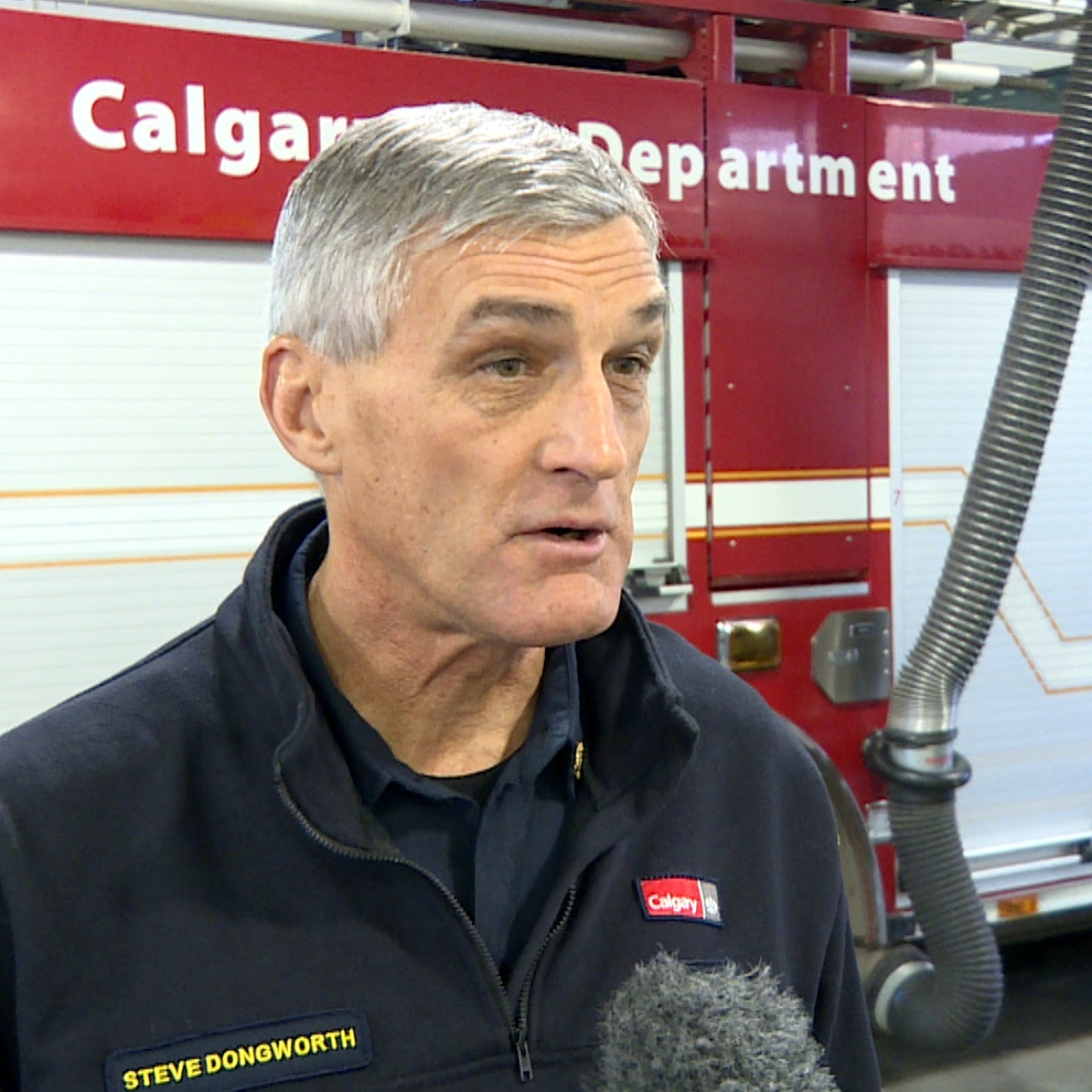

A letter detailing a workplace "crisis" was sent to Chief Steve Dongworth last summer from self-described "racialized, or otherwise marginalized members" of the fire department.

Initially, more than a dozen active and retired members were prepared to sign it, but ultimately the letter was sent without signatures after the employees decided the risk of workplace repercussions was too great.

The group described being "deeply wounded by degrading experiences" suffered at the hands of their colleagues and managers following years of trying to raise the issues with the chief.

"We have been ostracized, humiliated, degraded, slandered, undermined, ignored, verbally and physically assaulted, sexually harassed, and sexually assaulted," reads the letter, provided to CBC News.

It details allegations of racism and sexism that, in some cases, have contributed to suicide, the authors allege.

"People have killed themselves because of this culture, and I've been trying to tell people that for five years," said recently retired captain Chris Coy, who was the first Black firefighter to be hired in Calgary.

Although there are always complex reasons when someone takes their own life, both Coy and the authors of the letter suggest bullying related to the culture of racism has contributed to suicides.

CBC News has agreed not to identify four current members who confirm the hostile culture at CFD and are, according to one, "viscerally afraid" of retaliation. Two retired members have agreed to be named and two other people who spoke at the City of Calgary's three-day public consultation on systemic racism will also be identified.

Dongworth declined to grant an interview to CBC News and provided a written statement instead. He didn't deny racism exists within the department and said harassment and discrimination will not be tolerated. Dongworth also said CFD is creating a Safe Disclosure Office so members can report abuses.

CBC News requested information from the city, including the workplace reviews. Not only did the city not provide the reports, it did not acknowledge the request.

First Black firefighter says he endured 'torture'

Coy says that after being hired as the department’s first Black firefighter in 1996, he heard the N-word "every single day" for years, experiencing intense racism before climbing the ranks to captain.

Coy, who retired six weeks ago, says he decided early on that he would show up for work, push through and hope things would be easier for other Black firefighters who came after him.

He felt like he was channelling Jackie Robinson, the first Black baseball player in the major leagues, who endured racist taunts, hate mail and death threats.

"I made the decision that I would not react in any way, I would simply do my job to the best of my ability, I would play the role of Jackie Robinson, and that stayed with me my whole career," Coy said.

"It was torture, and it is still torture in a different way for the people that are there right now today."

He said the abuse he suffered as a rookie was tenfold compared with what his white counterparts endured. Firefighters would dump water on the other newbies in the first week of their rookie year, but Coy said he was "constantly wet," getting doused three to five times a day.

"I was never dry. Never."

On several occasions, he was physically assaulted at work, including once when he was slammed against a wall by a fellow firefighter who'd previously made his hatred of Coy clear.

Coy said his arm was then twisted toward the back of his neck: "I thought he was going to break my arm."

Over the years, he said, the racism became less overt and more insidious, as co-workers would get away with micro-aggressions.

In the fire hall, Coy said, every time the news covered a Black Lives Matter story, co-workers would get up and leave the room, roll their eyes or make snide comments.

"My colleagues, those like me, BIPOC members, refer to our fire stations as IDLH [immediate danger to life and health] environments," Coy said. "They're toxic environments. They're dangerous for us. They create damage to our mental and emotional health."

Although far less frequent, the N-word is still sometimes used in casual conversations in fire halls to this day, several CFD members told CBC News.

Dongworth, city well aware of festering racism, group alleges

Both Dongworth and the City of Calgary are well aware of the environment of racism and misogyny that has festered for decades in the city's 41 fire halls, the group alleges.

Coy says six years ago, he and three others met with Dongworth to discuss the issue not long after he was promoted from deputy chief to chief in December 2014.

"He knows all about it. We've been telling him for years. He knows about the suicides. He knows about the toxic culture. He knows about the abuses. He knows there’s been a mock lynching in one of our fire stations just a few years ago," he said.

"He knew all about it in 2015, and I'm sure he knew about it before then."

The city says it doesn’t track the number of firefighters who are people of colour. The members interviewed for this story estimate that less than three per cent of the 1,400 firefighters are BIPOC.

'The most trauma I've experienced is in the fire halls'

Last summer, spurred on by the Black Lives Matter movement, the city held a public consultation on racism.

Retired firefighter Shannon Pennington, who also heads a firefighter veterans' network, and Doreen Spence, a Cree elder, both made presentations about racism at CFD.

Pennington, who has First Nations roots, fields many late-night phone calls from distressed firefighters and has become an unofficial peer counsellor for those in crisis.

In his presentation, Pennington described an incident at Station 5 in south Calgary about 10 years ago, when a large pink panther stuffed toy was painted black and hanged by a noose from the rafters. The station had a Black firefighter on staff.

The panther was wearing one of the Black firefighter’s shirts.

"It should be every fire hall is a safe house to come home to," Pennington said in a telephone interview with CBC News last week.

But for members of colour, the fire halls are far from a safe space, he said.

"PTSD can come from calls, but the most trauma I've experienced is in the fire halls," said a current firefighter.

Firefighter who killed himself spoke of 'unbearable' racism

Doreen Spence, 83, who in recent months was awarded the Order of Canada, runs a mentoring program with students from the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary.

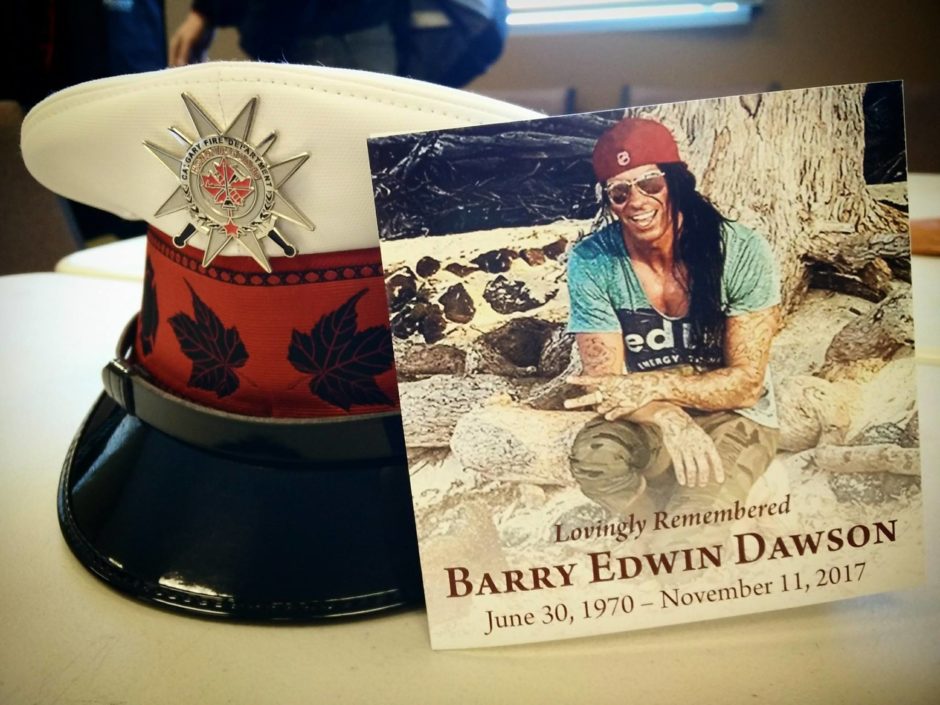

Elder Doreen, as she's known to those she mentors, also worked with fire Capt. Barry Dawson as he tried to connect with his First Nations identity.

Spence says she spoke with Dawson, who was 47, the day before he took his life in November 2017.

"Barry told me that the systemic racism was unbearable, and I could feel the sadness in his pain," Spence said during her presentation.

Dawson's time at CFD was fraught with battles over his hair and the fact that he was different — flamboyant, stylish, a former model.

As a rookie, Dawson was forced to cut his long hair or he wouldn't be allowed to graduate from recruit training, according to several people familiar with the situation.

Dawson’s hair was a huge part of his First Nations identity. Eventually, after a year-long battle in the mid- to late 2000s — which included pushback from Dongworth, before he became chief — Dawson won the right to keep his hair long.

"Barry took a lot of heat over being different," said one of his former colleagues.

Letter accuses chief of making it 'open season' on marginalized

In the letter sent to Dongworth last summer, the group addressed the chief directly, accusing him of being one of the leaders who made life difficult for Dawson when he was fighting to keep his hair long.

"At that time, you had the perfect opportunity to demonstrate true leadership, you could have come alongside Barry to support him and work with him to improve our workplace by revising outdated, racist policies," the letter reads.

"Instead, you took it upon yourself to engage in a campaign of relentless harassment and abuse of Captain Dawson, constantly criticizing his hair and deportment, in an attempt to have him conform to your idea of what a firefighter should look like.

"In doing so, you gave permission to everyone else in the department to follow your lead. It was then open season, not only on Captain Dawson, but also on every other marginalized member of the department."

Firefighter of Middle Eastern descent called 'turban twister'

Retired captain Anwer Amery — who's of Middle Eastern descent — says when he was hired in 1989, "it was abusive right from the beginning."

Throughout his career, he was called a "sand [N-word]," "snake charmer" and "turban twister" by colleagues, he said.

Like Coy, he also suffered several physical assaults, including being kicked, he said, and other firefighters made bets on how long it would take to get rid of him.

"There was lots of physical abuse — lots," he said.

Amery said he also watched as BIPOC colleagues were bullied to the point of quitting CFD.

Once he became a captain, he said he had trouble with some of his crew who'd become insubordinate. Human resources documents that he later got his hands on suggest his crew members complained about him.

One said he couldn't work with Amery. That firefighter, according to the union representative’s notes, was found to have offensive material on his cellphone, including a message where he expressed hatred for Chinese people.

Another would stare Amery down and refuse to respond to his captain's instructions.

Amery was also called a "f--king idiot" by one of his underlings.

He reported the incidents to his superiors, including battalion chiefs and captains.

Amery suspended without ever being given a reason

In January 2015, he was suspended with pay — without anyone ever explaining why he'd been taken off the job, Amery said.

Notes taken by a union representative and acquired when Amery asked for his human resources file back up that he was suspended without being given a reason.

"Anwer asked more than once for the reason he was being removed from the workplace but management was not willing to share that information," the union representative's notes read.

Initially, the union took up Amery's cause and filed a grievance for unjust suspension.

But when the city agreed to settle, Amery refused CFD's offer of $17,500 and a confidentiality agreement, as he instead wanted accountability for those responsible.

Amery was suspended until he retired in February 2016.

"If I could do it again, I would never join the CFD," he said. "I have seen the ugliest things you could imagine."

Workplace reviews not made public

In the past six years, the city commissioned two workplace culture reviews. The reports were never made public.

Amery attempted to acquire the first report from the city in October 2017 but was turned down.

In a letter sent to Amery, the city denies the existence of the report authored by lawyer Deborah Prowse, a consultant who specializes in respectful workplaces, human rights and conflict management.

"[The city] advised the applicant there was no report published by Deborah Prowse," reads a document sent to Amery.

"[The city] did not locate any responsive records."

But on page 6 of a diversity and inclusion framework document authored by CFD, the report is cited as "Prowse, D., Calgary Fire Department Report on Workplace Review, April 2014."

Upon filing a request under the Freedom of Information Act, lawyer Jean Torrens’s 2019 report was provided to Amery. Every single word was redacted.

'They feed off each other'

The firefighters who spoke with CBC News say it's not so easy to pinpoint why a climate of racism lingers in Calgary fire stations.

One current firefighter said the captain sets the tone for each fire hall, so if you have a bigoted captain, the rest will follow his lead.

"If he's racist, homophobic, misogynist, that's how they'll all act," the member said. "It’s herd behaviour … they feed off each other.

"There’s an overall feeling this is a club; we know we're outnumbered."

Letter urges 9 changes

Coy, Amery, Pennington and others say they have tried for years to create change. They’ve met with Dongworth, they’ve participated in workplace reviews and investigations. But still they watch and listen as co-workers who look like them continue to be bullied and harassed because of the colour of their skin.

They are sick of words. Sick of committees. Sick of workplace reviews. Sick of inaction.

In their letter, the group details nine calls to action:

1) A public acknowledgement of the severity of the toxic culture, with apologies issued to Dawson and Amery.

2) A public inquiry into job-related suicides.

3) Line of Duty Death (LODD) designations for members who died by workplace-related suicide and recognition of the PTSD caused by workplace abuse.

4) An independent centre of accountability to investigate workplace abuses and ensure appropriate discipline and corrective measures take place in a timely fashion.

5) A complete revision of the promotional process for chief officers with the involvement of front-line firefighters from marginalized groups.

6) BIPOC and female firefighter representation on every recruitment interview panel and promotional board.

7) Cross-cultural and anti-racism training for all CFD members, including education on the history of Indigenous genocide in Canada.

8) A zero-tolerance policy on workplace racism, bullying, harassment, assaults and other toxic behaviour, with breaches resulting in discipline up to and including termination.

9) A permanent place for CFD's BIPOC and female trailblazers to be recognized.

City and chief say CFD committed to improving culture

In its written statement, the city says it requires all CFD members to take an e-learning course on respect in the workplace.

"Any harassment or discrimination is unacceptable and will not be tolerated," Dongworth said in a written statement.

"We are committed to creating lasting change and making ongoing improvements in our culture. We are expanding our knowledge, acknowledging shortcomings, listening and learning."

Dongworth said his department is working with the city to create a Safe Disclosure Office for CFD employees to report concerns and access advice.

"One of my top priorities is to ensure that CFD focuses on enhancing diversity and inclusion and fostering a work environment where employees feel valued and respected."

While the fire department works toward making all of its employees feel respected in what can be a dangerous job, BIPOC members such as Coy feel the trust has already been eroded.

"Many of us don't feel safe; we’re not sure that they have our backs. Whether that’s true or not, only God knows. And them."

For more stories about the experiences of Black Canadians — from anti-Black racism to success stories within the Black community — check out Being Black in Canada, a CBC project Black Canadians can be proud of. You can read more stories here.