March 3, 2019

Kian Olsheski is a typical 17-year-old boy.

He spends his free time skateboarding, playing video games and hanging out with his girlfriend. A collection of limited-edition energy drink cans lines the shelves in his room, skateboard posters are plastered on the walls and his pet turtle swims around in an aquarium in the corner. He has a full set of weights for working out and bulking up.

But there is one big difference between Kian and his guy friends. For the first 13 years of his life, Kian was a girl.

"I remember as a small child, I would pray to God: 'Why did you make me the wrong way? Can I please wake up and just be the right way?'"

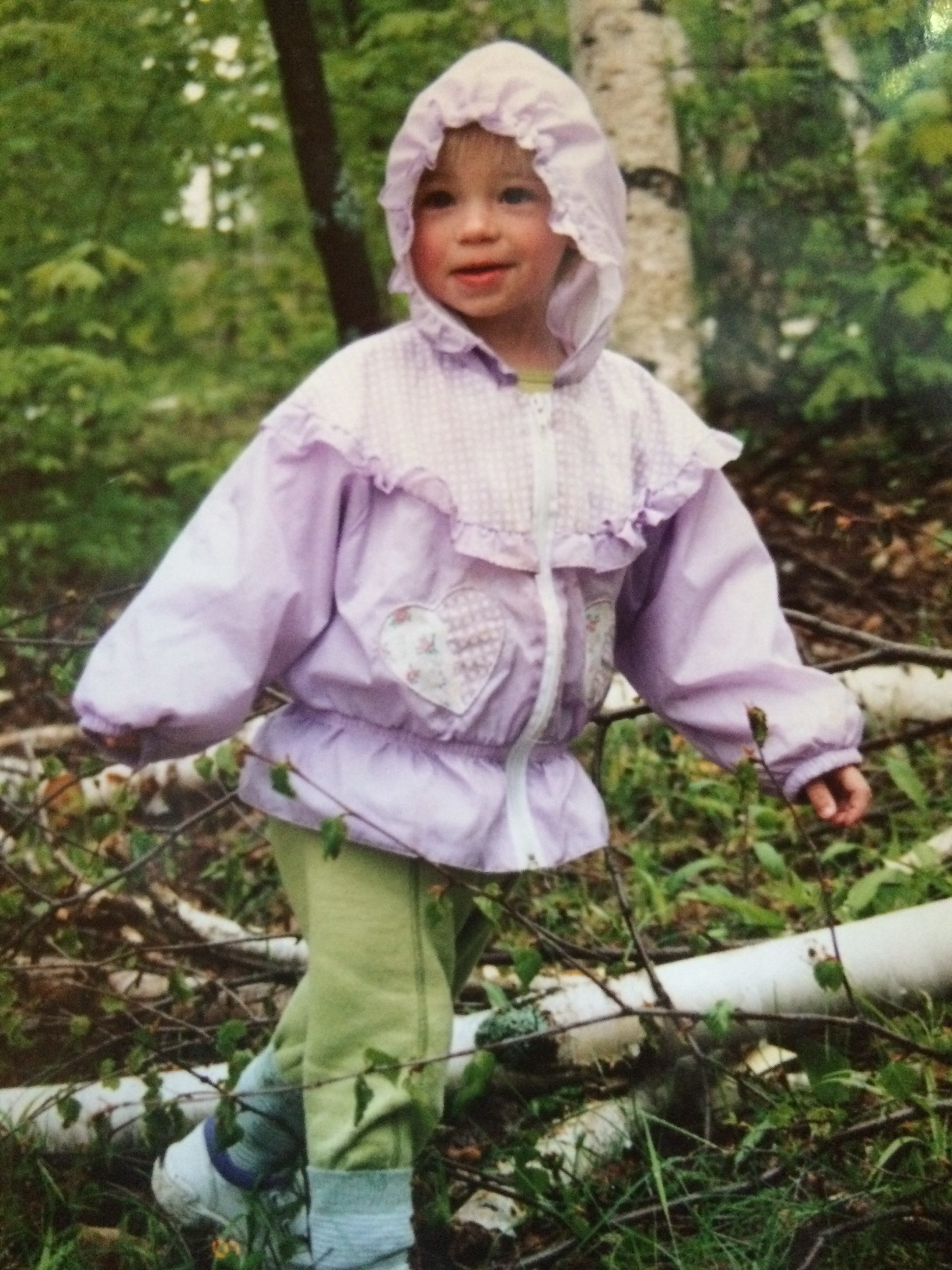

Kian was born Katlyn Anne Olsheski on May 24, 2001.

He grew up in Westmeath, a rural community in eastern Ontario that sits on the Ottawa River. Westmeath has a few dozen houses, a corner store, a school and an arena. And before Kian, it had never had an openly transgender teen.

Kian was a tomboy who hated wearing dresses and preferred hunting in the woods over shopping at the mall. Kian said he has known his whole life that he was in the wrong body.

"Ever since I was very little,” he said. “In my dreams and stuff, I'd be ... a guy.”

Kian may have been something of an anomaly in Westmeath, but across the country, kids like him are seeking help in increasing numbers. Children's clinics are seeing exponential growth in demand for treatment from teens who don't identify as the sex they were born with.

The past four years have been a long and difficult journey for Kian — his teen years have been filled with appointments, hormone treatments and surgeries. But Kian wouldn't have it any other way, because the process saved his life.

"I'd say my whole life now is way better," said Kian. "I enjoy my life and I think that none of it would have happened if I didn't decide to come out."

The first time Kian heard the term transgender, he was nine years old. His fraternal twin sister, Kirstyn, told him about a news report on a girl who transitioned to being a boy. Kian immediately wondered if he could do that, and began scouring the internet for anything to explain what he was feeling.

“There wasn't a day I didn't think about it, and I couldn't stop thinking about it. And that's kind of how I knew that that's who I am.”

But transitioning in a rural community seemed like an impossible dream for Kian.

“Around where I live, you don't really see that happen … It wasn't really in the media that much, either. So it was basically like, OK, I have these feelings, but there's no way I'll ever get a chance to actually live my life like this.”

Kian kept his feelings bottled up inside until he was 13. But pretending to be a girl was driving him insane.

"I just kind of started hurting myself and having thoughts, like, I don't want to go on like this."

Kian was cutting and burning himself.

"I didn't want to live as Katlyn anymore, because it wasn't who I was," said Kian. "I didn't want to keep living as somebody else."

All of that changed when his classmates noticed the marks on his body. That’s when his teacher called his parents, Kent and Lee-Ann Olsheski.

At that point, Kian figured he had nothing to lose. It was time to come out.

"I had been in this kind of dark place for a while and it was always like, it's either going to end here or I'm going to tell people who I am. And I kind of just figured like if, worst-case scenario, I'm ending things, I might as well tell people who I am first and see how it plays out."

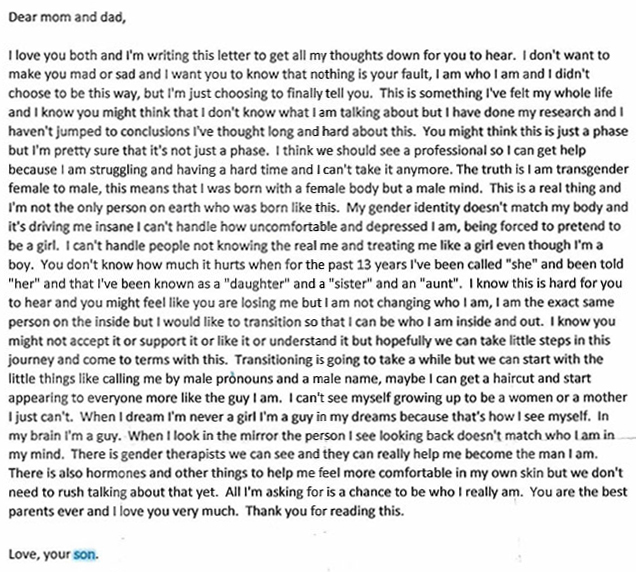

Unbeknownst to Kian's parents, the teen had been spending a lot of time trying to figure out how to come out. He'd been struggling for a year, writing and rewriting a letter to them.

Even though his parents were open-minded and progressive, he was petrified to give it to them.

“I was just prepared to have bags packed and leave if I had to,” said Kian.

The letter told his parents what was going on in his mind.

"The truth is I am transgender female to male, this means that I was born with a female body but a male mind," he wrote.

"My gender identity doesn’t match my body and it’s driving me insane I can’t handle how uncomfortable and depressed I am, being forced to pretend to be a girl." He signed it, "Love, your son."

His parents had no clue. Despite the shock, they immediately told Kian they loved him and that they would support him.

Even so, they were worried.

"The first thing I said is, 'Boy oh boy, he's going to have a rough life,'" said Kent Olsheski.

"And how do you explain this to family first ... and then friends?" said Lee-Ann Olsheski.

"I just was worried about how he was going to be treated in the community and in school," said Kent. "Pretty tough thing to go through in this community."

Kent and Lee-Ann started using the male pronoun for Kian right away, and overall just decided to follow his lead.

"You love your children and you want to do anything you can for your children," said Kent. "I've heard horror stories ... where parents almost disowned their child because they came out and said that. You absolutely can't do that."

“They basically just said, ‘We'll listen to you, and you can tell us what you need to be happy.’ So that was the best-case scenario,” said Kian.

Within a few days, Kian cut off his long blond hair and started the process of changing his name and gender on all his identification. His parents set up an appointment with his family doctor and Kian was referred to the gender diversity clinic at CHEO, a pediatric health and research centre in Ottawa.

A team of doctors at CHEO assessed Kian. They concluded his gender dysphoria was so intense that he needed to be treated as soon as possible. Within a few months, Kian was on hormone blockers to prevent him from going further into puberty. His periods ended and his breasts stopped growing. He soon started taking testosterone to develop masculine characteristics.

Over the next three years, Kian underwent two surgeries at CHEO — one to remove his breasts and one to remove his uterus.

“I can, you know, take my shirt off in the summer at the skate park. I can do what I want, and with the [hysterectomy], it was life-changing," he said.

When he turns 18, he can get reconstructive surgery to fully transition.

Despite all the major surgery, Kian hasn't had a moment’s doubt.

“I've been a guy my whole life. It's just making the outside match what's inside.”

One of the first people Kian came out to was his close friend Morgan Campbell, who wasn't surprised.

"If you knew him before, you could tell he was masculine," said Morgan.

What was somewhat unexpected was that before too long, these two good friends became a couple.

"I was just ready to ... support him, and I didn't know that I was going to fall in love with him," said Morgan.

Kian came out in May, went on his first date with Morgan in June, and by November, they were officially together. They have been inseparable ever since. Kian said he couldn't have transitioned without Morgan by his side.

"She's my girlfriend, but she's also my best friend, so I've always had her by my side. So even if nobody else wanted to hang out with me or talk to me, I always had her," said Kian.

Morgan knew that dating Kian was going to complicate her teenage years, but she said they had a connection.

Surviving years of bullying together "really just made us both stronger," said Morgan.

Kian was physically leaving Katlyn behind, but in a rural community, it’s hard to hide who you used to be.

“The word was spreading about me and then everybody else had their own thoughts about me before they even met me. So I think that made things hard at the start,” he said.

“I don’t think people were comfortable with what I was doing, so they took it out on me.”

He said one of the refrains that was going around was that "me and Morgan were lesbians.” Kian said he never held a grudge against these nameless accusers, but what hurt the most was that people were saying it behind his back.

“If you're going to say something about me, come say it to me, we'll talk about it."

Kian said the worst part of the process was that he couldn’t escape his identity as “the trans kid.”

“That's probably been the hardest part for me, because ... that makes it hard for me to live my life normally.”

It was difficult for Kent and Lee-Ann, as it would be for any parent, to watch their child endure all this bullying. Kian never wanted to make a scene, and refused to let his parents speak up when people still referred to him as a girl.

"The hardest part for me was, he wouldn't let me say anything," said Kent. "Lots of things happened with hockey, lots of things happened in the school."

Lee-Ann said her mama-bear instinct would kick in, and she would have to speak up.

"Some of [the people], you stop and explain it to them, but they still don't understand," said Lee-Ann. "They'll say, 'I thought ... you have two daughters,' and I say, 'No, I have a son and a daughter.'"

The bullying didn’t stay in the high school hallways. It spread to the hockey rink.

Throughout his childhood, Kian and his twin sister played hockey on girls’ recreational and competitive teams. When Kian started transitioning, he didn’t want to play with the girls anymore, so he went to play with the boys on a house league team.

Kian said he was treated poorly by his teammates and coaches. Even other parents started talking about him behind his back.

“They basically didn't really know what to do with me … They had meetings about me to kind of tell parents and teammates how to treat me.”

Kian was allowed to go into the boys' changeroom with his teammates, but he still felt out of place.

“I would never get changed in the room. I would go into the bathroom, put my Under Armour [clothing] on, come back out, then put the rest of my equipment on with everyone."

The last straw came when his teammates locked him in the bathroom at an away game.

“They were saying, ‘Oh yeah, it was an accident,' or 'It was just a joke, like, he knew.’ And the coach was like, ‘It wasn't a joke.’ He knew that they had locked me in there. And I went out, played that game, came back in, changed and that was the last game I ever played," Kian said. "I just kind of said ... ‘Goodbye, I don't need this.’”

That’s when Kian quit the game he loved.

Kent and Lee-Ann had at one point talked about moving out of Westmeath to a bigger city. But in hindsight, they're glad they didn't. They can see now how attitudes have changed in their community, and how people can become more open and understanding.

Kent said there is much more awareness in Westmeath about trans issues "than there was a few years ago, and that's because of Kian."

It took years, but people are finally starting to accept him for who he really is. People who used to bully him are texting him to say sorry. Attitudes are “completely changing now. Like a 180 type of thing," said Kian. "I'm who I am now and I'm happy, but now everybody else is kind of able to see that, too.”

After the turmoil of the last few years, Kian is now looking forward to his future. He’ll be graduating from high school in a few months, and he's heading to university in the fall.

He’s already looking for an apartment with Morgan and is looking forward to leaving Westmeath — and Katlyn — behind.

“It's just going be nice. I can walk into a room and everyone in it just judges me for me … instead of what they heard about me. Or what they knew about my past."

Jen Beard is CBC Ottawa's digital producer. You can reach her by email jennifer.beard@cbc.ca.