November 12, 2018

Dara Cowan hasn't been able to finish her renovations. She’s been on medical leave for a year with no disability payments. She’s also in the process of separating from her husband.

The unfinished stairwell to her basement is right next to the kitchen. There’s no rail, so she piled books, toys and boxes, creating a makeshift safety wall to keep her children from falling.

This haphazard approach, using whatever resources she can scrape together, is not unlike how she’s grasping for ways to shield herself from scorn in her small community of Gravelbourg, Sask.

Cowan said she was sexually harassed by Roland Levac, the former leader — the reeve — of the municipal council in the small, rural community. Levac ended up resigning and admits some wrongdoing on his part.

According to Cowan, members of the council bullied her for doing her job as an administrator after the reeve was gone. She said she was trying to get them to abide by provincial legislation that governs them.

The RM has denied any harassment ever took place.

Cowan said her experiences are part of a wider culture of bullying and harassment at rural municipalities. She said the system leaves workers vulnerable.

She has no income because of a technicality that made her ineligible for Workers’ Compensation payments and she is not receiving any short-term disability payments through her job.

“I know why people don't come forward,” she said.

“I know why people just live in silence. I understand that completely. But things need to change, whether it be legislation or procedures. It needs to be changed. They need to be accountable for their bad behaviour.”

Cowan’s experiences are not unique.

Workers in communities all over the province said they have been bullied and harassed on the job.

Some expressed concerns for their physical safety. Others are facing financial trouble after long periods on medical leave. Some left their jobs. Others left town.

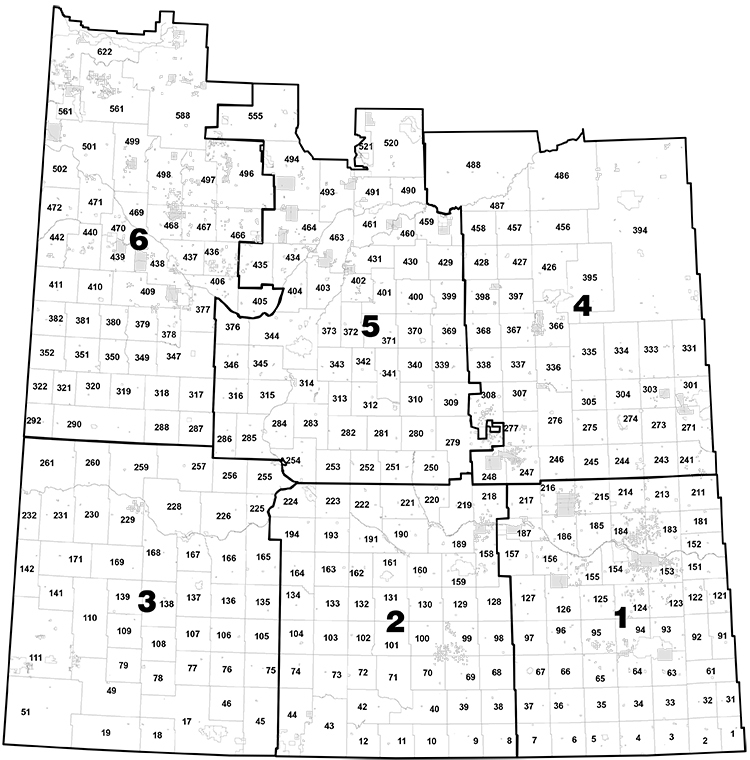

Saskatchewan has 296 rural municipalities (RMs). Some serve populations as small as 100 people. In many RMs most residents know each other. It’s easy to see how governance decisions can devolve into personal feuds.

RMs usually operate with very little oversight from other levels of government. Issues like bullying, harassment, conflict of interest and legal non-compliance can fly under the radar for years. When complaints are investigated, it’s often up to the RM what to do with the findings.

Do you have a story to share of bullying or harassment, conflict of interest or lack of transparency at a small town government in Saskatchewan? Email Alicia.Bridges@cbc.ca

Inappropriate behaviour may 'lead to charges'

The high-profile case of Robert Duhaime, who took his own life after making accusations of bullying against his RM employer, brought the issue of bullying into the spotlight.

Now some RM administrators, councillors, reeves and employees are saying the province needs to step in to hold bullies accountable and force systemic change to eliminate dysfunction.

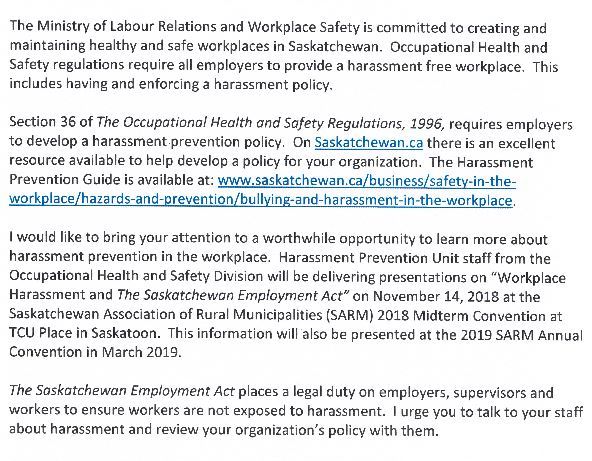

The provincial government recently acknowledged bullying and harassment at RMs as a problem for the first time, warning municipal leaders to bring themselves in line with the law.

Minister for Workplace Safety and Labour Relations Don Morgan said more “aggressive” measures would be considered if the problem persists.

“I have met with some of the councils and told them that what they are doing may well be inappropriate and may well lead to charges being laid against them,” said Morgan.

But victims like Cowan say they will still be left vulnerable unless there is systemic change, complete with new safeguards.

Much of Saskatchewan’s population of about 1.1 million is centred in its two biggest cities, Saskatoon and Regina, but most of the land in the province falls under the governance of rural municipalities.

The 296 RMs serve a total of about 176,500 people, according to the 2016 Census. That’s approximately one local government for every 500 people.

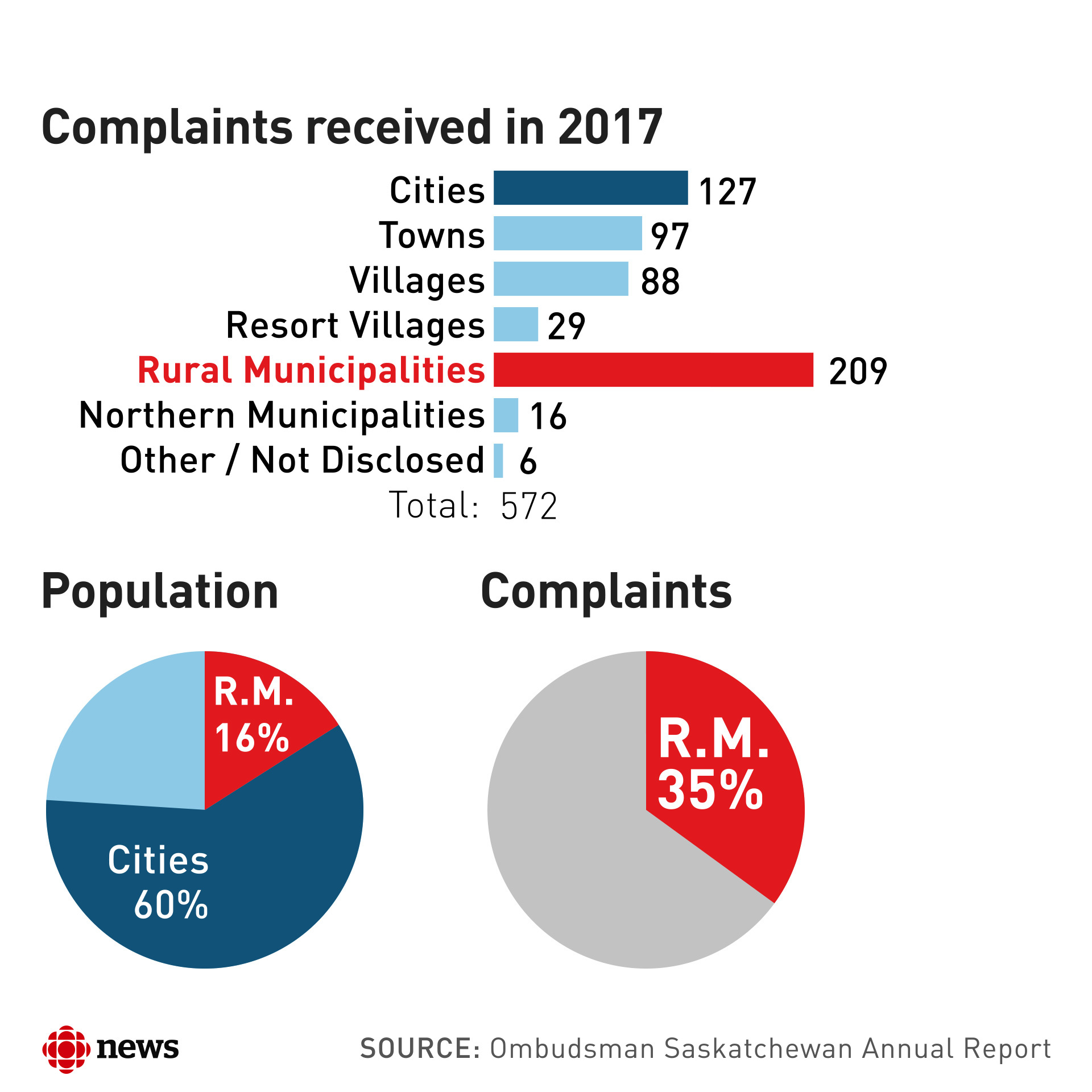

Although RMs make up about 16 per cent of the total provincial population, they were the subject of about 35 per cent of complaints to the provincial ombudsman about municipal governments last year.

The majority of complaints were made by an employee, a former employee or a council member. It’s not clear how many of those relate to interpersonal issues.

Marilyn MacKenzie, a Manitoba-based employment consultant who has dealt with harassment and bullying cases in Saskatchewan, said small-town dynamics combined with a lack of oversight allows personal grudges to get in the way of governance.

MacKenzie emphasized that many RMs do follow the rules, but said she has seen cases of favouritism by councillors to their friends, ignorance of the rules, slander, libel and nervous breakdowns.

She said she has seen victims of bullying suffer extreme stress, weight gain, weight loss, even heart attacks.

MacKenzie said people caught in a toxic environment can find themselves unable to speak up for fear of being targeted further or losing their jobs.

She once found that an interpersonal dispute within an RM was related to a breakup between the complainants’ respective children.

“It’s that kind of a petty, almost junior high kind of behaviour. And again I think it’s because the structure is such that they don’t really have to report to anybody officially,” MacKenzie said.

“It’s a small town and people get inside information on each other and biases are formed and alliances are formed.”

'I felt like I didn't have a choice'

Cowan attributes muscle-spasms, depression, anxiety and lack of sleep to what she experienced at the RM of Gravelbourg.

When she started getting extra attention from the former reeve Roland Levac — who was also her boss — she wondered if she was misreading the situation.

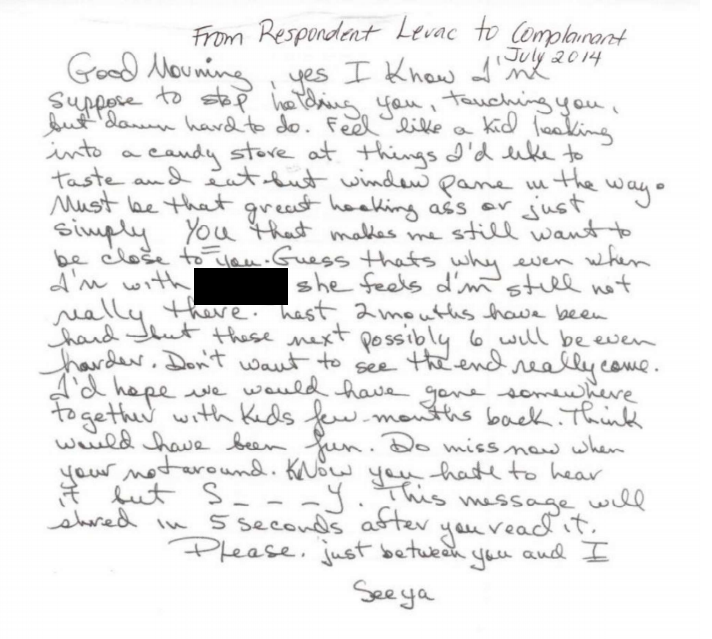

She had been working at the RM for about four years when she realized Levac wanted a relationship. In 2014, he started leaving her notes. One of the first wished her a “happy administrator’s day.” Soon the notes became more intimate.

“He used to tell me I was like looking into a candy store. Candy that you want but you can't eat and you can't have,” said Cowan.

“I suppose if you were welcoming that relationship that might be something nice. And I think in his brain he thought that was something nice and flattering. I just felt controlled. That I had no say in what was happening to me and it didn't matter how many times I said stop. It wasn't stopping.”

Cowan said she was already dealing with a separation from her husband at the time. She said Levac made advances under the guise of helping her transition out of the relationship.

She said they were friends initially. She allowed him to help her at home. Over time his visits became uninvited.

Cowan said people in the small community began to think she was sleeping with the former reeve, who was married. She started to notice people treating her differently.

She said Levac once put his hand on her leg in a vehicle in front of someone else. Cowan said she didn’t speak up because she was worried there would be repercussions.

“I felt like I would be let go for sure in one way or the other. I felt like I didn't have a choice,” said Cowan.

“I felt stuck and everything was happening so fast that I was having a hard time wrapping my brain around what I should do next.”

Levac doesn’t deny he wrote the notes or that he touched Cowan, but he said they were in a non-sexual relationship except for what he described as hugging and kissing.

“I don’t know, was I the one that totally did it all? The response was still there, so how do you pinpoint that. Like she still kissed me.”

He said Cowan never said anything to suggest his attention was unwanted until after what he describes as the end of their “relationship.” Cowan said she did not initially tell Levac to stop because she thought she would be fired. Levac denied his position of seniority over Cowan played a role in her decision not to speak up.

“You think that OK, because I'm the boss you're looking at the possibility ‘Well if you don't work with me then I'm going to get you fired.’ No, that was — as far as I'm concerned she knew exactly at that point that I had this relationship with her but it had nothing to do with her job whether or not she was still there or not,” said Levac.

“She wanted to leave and I said ‘No you're not.’ I simply told her that she deserved to have the job, [that] what I had done I guess was wrong at the time and that it was my position to leave not hers.”

Levac resigned in December 2014. Cowan said she hoped things would be better, but Levac would still visit the office. Cowan believes he was there to influence the decisions of council.

Cowan said some members of council became hostile towards her over the next three years, particularly when she raised concerns about possible conflicts of interest or breaches of The Municipal Act.

In one instance, she said a councillor raised his voice and yelled “that’s bullshit” when Cowan raised concerns about a potential conflict of interest. In a subsequent investigation into a string of allegations Cowan made against the RM, one witness supported the claim, and two others denied it.

The current reeve of the RM, Guy Lorrain, denies any harassment occurred.

“What she calls harassment is just asking questions,” said Lorrain.

Report without fear

Cowan said she believes it is in the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities’ (SARM’s) best interest not to crack down on RMs because there is monetary gain to be had.

Each RM pays to be a member of the association. SARM can lobby the provincial government for tougher measures and push for a change of culture with initiatives such as training, but enforcement of the law lies with the province.

Wendy Gowda, president of the Rural Municipalities Administrators Association and a member of SARM’s board of directors, said she’s aware of administrators facing personal backlash for speaking up against a conflict of interest.

“It has to be OK, often in a conflict position … to report these things without fear of reprimand or fear of job loss, or anything like that. I think it can be very difficult in a small person office,” she said.

“Especially if there is conflict, the people that are your bosses they are the people that you deal with. So if there is some kind of controversy there it can be very difficult.”

Gowda said efforts are being made to improve conditions for rural employees and councillors, but that options for seeking help are limited.

With limited jobs in rural areas, some workers choose to leave town rather than risk further complications from making a complaint.

Cowan eventually took her situation to Occupational Health and Safety.

In March 2017 she filed a harassment complaint against the former reeve for sexual harassment and a personal harassment complaint against two members of council.

As per the requirements of OHS, the RM hired an independent investigator, Kn/a HR Consulting, which looked into both complaints.

The investigation concluded that in two of Cowan’s eight allegations, sexual harassment had occurred: the notes that Levac had left Cowan and inappropriate emails he sent her containing graphic material.

The HR firm concluded there was not enough evidence in the other instances to support her claims of harassment. In one example, Cowan said Levac “commented on the dress she was wearing and put his hand really low on her back.”

'They just seem to get away with it and they know it'

Kn/a deemed there was not enough evidence to support the claims of touching, and that “the complainant [Cowan] failed to make it clear to the respondent that his behaviour was not welcome. The complainant did not tell the respondent to stop the behaviour, nor did the complainant report the respondent’s behaviour to the employer.

Although the RM of Gravelbourg policy does not say to tell the harasser to stop, it is a reasonable expectation to tell a harasser to stop unless one feels threatened to do so. At no time did she say she felt threatened. Further to this, a reasonable person may not have known that the behaviour was unwelcome.”

The current reeve, Guy Lorrain, said the sexual harassment claim has “no jurisdiction pertaining to us” because it occurred before the current council was elected.

The investigation into the complaint against the other members of council concluded that no personal harassment had occurred.

Cowan remains on medical leave. She said does not feel comfortable returning to work.

The council did not make any changes after the findings that sexual harassment had occurred. Cowan said this shows councillors will not be held accountable. She said Levac is free to visit the office at any time.

“They just seem to get away with it and they know it. And at some point that becomes an arrogance. ‘We can do whatever we want,’ ” she said.

“There's a common thought, and it's been said many times in meetings and recorded meetings even, that The Municipalities Act is just a guide and it's not for us little RMs. It's for those big RMs.”

Systemic change

There are other stories of bullying, harassment and overall dysfunction all over Saskatchewan.

The impact of Robert Duhaime’s death was felt at RMs across the province. Duhaime was a grader operator at the RM of Parkdale. After he took his own life on Aug. 31, 2017, the Workers’ Compensation Board attributed his suicide death to his employment.

Some RMs that did not have anti-bullying policies have since started developing them.

The RM of Parkdale denied Duhaime was bullied at work and appealed the WCB decision. Reeve Daniel Hicks told CBC Radio at the time he did not know what bullying was until after the death.

“I’m an ordinary guy, I don’t even know what bullying is,” said Hicks.

Another grader operator in the province, who CBC has granted confidentiality to protect his employment, said that his job is affecting his mental health.

“I heard about panic attacks, I heard about anxiety, stuff like that, I never believed that,” he said.

“And then all of a sudden I come here and within six, seven, eight months I’m already ready to go into the loony bin. It’s stressful to go to work because everything you did was wrong.”

In 2012, an independent review of the RM of Corman Park recommended that officials receive professional counseling on how to behave and act like a representative body.

It described council members behaving like bullies and dictators. Problems including lawsuits alleging harassment, unjust dismissals and conflicts of interest.

Judy Harwood, who was elected the new reeve of the RM in the year the report was released, said she ran for the position to try to clean up the problems.

She said administrators have to be strong to push council to do things they don’t want to do.

“I would say 85 per cent of the administrators in our province are women and probably 85 per cent of the councillors are men so you do the math and figure it out,” she said.

Another administrator, who CBC also granted confidentiality for fear of losing her job, said she was targeted for refusing to commit fraud and had to turn to police when she began to fear for her personal safety.

“I was stalked, my car was keyed, they’d come in and they’d record conversations and then threaten me,” she said.

She said systemic change within RMs would need to come from the province because it’s unlikely to come from within.

“They’re uneducated farmers for the most part on these councils,” she said.

“I don’t think they understand their responsibility as elected officials and as ultimately, employers.”

University of Saskatchewan political scientist Joseph Garcea said RMs could be at a turning point that could lead to change.

“There may be a new generation that is being trained in terms of more education and also has more organizational experience, service experience, that perhaps the previous generations who are still serving may not have,” he said.

In the meantime, problems persist.

In one instance, an interpersonal issue that started on council spiralled into violence outside the RM office.

A former councillor at the RM of Emerald was convicted in 2018 of assault causing bodily harm for punching the reeve, years after tensions between the two started while they were on council together.

Another case that made it court in 2018 stems from the RM of Blaine Lake.

Bertha Buhler was an administrator there until 2017. In her resignation letter she wrote that, “the continual barrage of verbal assaults, harassment, and pressure against the CAO to execute the duties of the CAO in a manner that is unbecoming, morally unethical and without motion of council is unacceptable. This continuing action has led to a highly toxic work environment that jeopardized the health, safety and personal well-being of myself in such a manner that I find there is no other recourse to protect myself but to resign as CAO.”

Court documents show that Buhler’s complaint was about the reeve, William Chalmers. Councillors passed a bylaw to remove the reeve from municipal duties and responsibilities, prohibiting him from representing the RM to external bodies or individuals.

The motion passed 5-2, including the reeve’s own vote against the motion.

Chalmers did not respond to requests for comment. Court documents show he denied the allegations against him, adding that he had never been provided with any details of a single circumstance of harassment. He took the RM to court, saying it breached its own harassment policy by revealing his identity and failing to do its own investigation of the complaint, and that the RM did not have the authority to remove him.

A Court of Queen’s Bench Judge in Saskatoon agreed with the RM that it had the authority to remove him, but an appeals court recently reversed the decision.

The appeals court judge reasoned that council did not have the legal authority to effectively remove the reeve from his position by resolution, adding that only the Lieutenant Governor in Council can do so. Having already ruled in favour of Chalmers, the court did not address his claims of unfair treatment.

The RM’s argument that it was not removing the reeve, simply preventing him from chairing meetings, was not accepted by the judge.

Some RMs have never introduced bullying policies

Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) encourages people being bullied or harassed to make a complaint. Inspections and audits are unlikely to happen otherwise.

The administrator who said she was asked to commit fraud said that if she contacted OHS she would have been identified.

“I was living in the community, the members of council were very prestigious members of the community,” she said.

“So if I would have said anything about that, I would have been blacklisted, I probably would have been run out of town.”

She said many people who experience bullying likely do not report it for the same reason.

OHS does not track stress leaves but said it has received 85 complaints about harassment and bullying at RMs since 2014. Of those, 35 were deemed to meet the requirements for a follow-up.

The administrator added that the province had not implemented whistleblower protections at the time.

“So as an administrator, where do you go? You have no place to go, these are the people who have hired you, these are the people who work for you, and these are the people who will fire you. So you have nowhere to go. And so ultimately as an administrator, you leave, because you don’t have an alternative.”

Although she said some RMs and councillors treat their employees — and each other — very well, a lack of protection means the workplace environment is a matter of luck.

OHS executive director Ray Anthony acknowledged that while the law that requires bullying policies was introduced more than 10 years ago, some RMs have never introduced them.

“We can’t enforce what we don’t know. If someone doesn’t phone in and say I’ve been robbed, you can hardly blame the police for not acting on it,” Anthony said.

He said it is the responsibility of the employer to know the laws that apply to their workplace and comply with them.

OHS has 63 staff to do field inspections of employers around the province. It has received around 1,800 complaints about employers in the past two years, with 90 per cent relating to psychological health and safety.

Anthony said callers can request confidentiality when they contact OHS. He said he would not consider the number of calls from RMs to be high.

Administrators and other workers who have experienced bullying or harassment, or seen it occur, seem to agree that mandatory training for new councillors could help.

The provincial government is implementing similar training for MLAs, who already receive one-on-one conflict-of-interest training when they are elected.

Wade Sira, Reeve of the RM of Rosedale, said he got exasperated by the behaviour he has seen on council and tried to garner support for a proposal that all new councillors must undergo “dos and don’ts” training.

“There is no consequences for when council does go beyond what they’re supposed be doing,” said Sira.

“There is no one to enforce it; council is accountable to themselves.”

He put forward a resolution at his division meeting of the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities June.

He proposed that councillors be required to undergo training within three months of being elected or lose their seat. Those already on council would have six months to complete training, or relinquish their seats.

Sira’s proposal didn’t pass. Even if it had, it would still have needed to be approved by SARM delegates in other divisions across the province before the association would endorse it.

“It’s a small room. I could hear people saying ‘it’s a good idea but it’s never going to work,’ ” said Sira.

“Who really wants to hear what they have been doing is wrong, or what they shouldn’t be doing? A lot of people don’t want to hear that.”

Wendy Gowda, from the Rural Municipalities Administrators Association, said she was involved with previous efforts to promote education about bullying and harassment in the workplace. She is skeptical that such a move would ever get enough support to be voted in.

Gowda added that elected officials sometimes run for council because they want input on a specific issue. They may not want to approve a change that would increase oversight over their conduct.

“How we can emphasize more about the need to be cognizant of harassment? I’m sorry, we really try hard,” she said.

Gowda said she too has experienced bullying in her role as an administrator.

She said that in a former role she was brought in annually to negotiate her own salary without any hope of having influence on the outcome, a process she believes was carried out as a form of humiliation.

Gowda said she was also directed to do additional work that did not seem to have any value to members of council.

“Even if I felt I had support amongst the majority of the council, when there is a bully at the table sometimes it’s difficult for anybody to step up,” she said.

“Most individuals that are interested in becoming an elected official really are passionate and care about their municipality and they don’t come on board to dispute and argue and fight.”

Gowda said RMAA has worked with the Ministry of Government Relations to create a peer support network for administrators.

The program is a pilot based on something similar in Alberta. It’s meant to provide support and advice in situations where there is nobody local to turn to.

“Especially in remote areas where they don’t have anybody to talk to or maybe they don’t want to be talking to their council,” said Gowda.

“Just to have some more support and maybe lend an ear to listening and have some suggestions for how to get through some of these moments before they escalate.”

Mandatory training unlikely

SARM president Ray Orb said the association will not push the province to make training mandatory.

“Unfortunately if we push too hard to force our officials to take the training there may be people that decide not to run for council,” said Orb.

“That would depend on what’s being asked. Something that’s quite straightforward I think our officials would be willing to take that sort of thing but I think if it’s too onerous … it may actually deter some people and we certainly want to encourage people to get involved with rural councils.”

Orb said SARM will continue to offer training and it is considering incentives to encourage councillors to take part.

He acknowledged that the shortage of administrators in RMs could contribute to bullying and harassment.

It appears any change would need to come from the provincial government.

Orb said SARM would welcome a provincial review of RMs depending on who co-ordinated it. He said RMs should also have a chance to contribute.

“We offer training to everyone and if some people don’t take it we’re a bit concerned about that, we’re trying to actually figure that out, to be able to cope with that problem, to be able to attract people to be able to take courses.”

Manitoba has publicly acknowledged the trend of bullying and harassment on RM councils in that province.

Manitoba began holding consultations in April to hear from victims and municipal politicians.

Advocates in that province have suggested mandatory videotaping of meetings and appointing an “integrity commissioner.”

Province to send letters to RMs outlining expectations

In Saskatchewan, Minister Don Morgan said he is aware of bullying and harassment incidents that are “extremely concerning.”

“People get elected as councillors, we expect as citizens that we should get leadership from them and appropriate conduct not just in how they treat their employees but in all aspects of how they conduct themselves.”

Morgan said the province will be sending letters to rural municipalities outlining the expectations and responsibilities of being an elected official. CBC was told the letter was being finalized and will likely be sent out mid-November.

“What I would say again to the workers, if they are in a situation where they're not getting an adequate response from the ministry, come back and see us again and we may well lay a charge against the municipality or take further steps.”

He said mandatory training for councillors could be one of those steps.

Asked if the province would consider holding a review and consultations similar to those in Manitoba, he said his ministry has not ruled anything out.

The provincial government is also reviewing The Municipalities Act as part of a routine review of legislation but said it is too early in the process to determine what amendments, if any, will be made.

Amalgamation

Victims and advocates have also raised amalgamation as one way to improve the efficiency and oversight of rural municipalities.

In 2000, Joseph Garcea, the U of S political scientist, authored a report on municipal reform that recommended creating 125 municipal districts. The document was commissioned by the then-NDP government.

“Smaller local governments tend to be — their virtue is also their problem. They’re very close to the people and the employees and the councillors know each other and work together very intimately,” Garcea said.

“That’s on the positive side but on the problematic side sometimes they don’t abide by existing policies, norms, in terms of dealing with employees.”

He said the report identified “a whole series” of problems related to the interactions between councillors, administrators and employees.

“We also heard that many administrators were frankly concerned about potential dismissal if they didn’t do things according to the way council wanted them done,” Garcea said.

The report was met with staunch opposition from members of the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities — which continues to resist amalgamation — and the recommendations were never acted upon.

The Saskatchewan Party government confirmed it “has not and will not” consider amalgamation.

“The government is focused on regional cooperation as opposed to forcing boundary changes,” said government relations Minister Warren Kaeding in an emailed statement.

“There are many opportunities for municipalities to work together or restructure voluntarily, if local ratepayers choose to move in that direction.”

Kaeding said the province will help support municipalities that want to restructure.

Dara Cowan doesn’t know if any changes made now would help her, but she hopes they could help other workers in the future.

Right now she remains in limbo. Unable to return to work, she has been gardening and tending bee hives to pass the time.

She worries that the coming winter, with months of being confined to her home, will make things worse.

She loves her home, sitting as it does behind a low stand of evergreens on a rural Saskatchewan road. With no income coming in, she worries she may have to leave.

Every trip to Gravelbourg — taking her kids to school, attending medical appointments — takes her past the homes of some of the people she said harassed her.

She said she’s not sure she could take another job in municipal government.

“I don't know if I would want to do it again, and it's a job I loved, and I was really good at it,” said Cowan.

“I just don't think I ever want to be put in that position again. I don't ever want to give someone that much control again over my well-being.”

Anyone experiencing harassment at work is asked to contact Occupational Health and Safety at 1-800-567-SAFE (7233).