It doesn't take long for residents of Ingersoll, Ont., to explain why they're against a plan to turn a limestone quarry just outside their town of 12,000 into Ontario's fifth largest landfill.

There's the odour.

The 150 daily visits by trash-hauling trucks.

And the principle of allowing 17 million tonnes of trash — most of it from outside their community, much of it from Toronto — to be dumped into a 30-metre hole not two kilometres from downtown.

But to Bryan Smith, who heads OPAL (Oxford People Against the Landfill), a citizens' coalition that boasts 400 members, it comes down to something else.

"It's all about the water," he said. "When you put trash into your water, you end up drinking it. And this is a community that drinks groundwater. We're very close to the banks of the Thames River. Any natural leakage would end up in the river. You don't live without water and that's why we’re committed to this."

Fierce opposition

Located in the heart of southwestern Ontario, Ingersoll is 150 kilometres down Highway 401 from Toronto.

Though the proposed landfill will take trash from across southern Ontario, most of the anti-landfill lawn signs in the area radiate their anger back up the highway, toward Ontario's largest city.

"OPAL says 'no' to Toronto Trash," reads one sign. "We are Not a Willing Host," another says.

Ingersoll Mayor Ted Comiskey puts it another way.

"We are not Toronto's kitty litter," he said.

The fight over the proposed landfill highlights a looming problem: As Ontario dumps fill up, smaller towns are pushing back at the idea of taking in trash from the larger cities. And while these pressures grow, the waste industry says dump approvals are a long, exhaustive process, with the province already taking up to 10 years to approve each new application.

The proposal

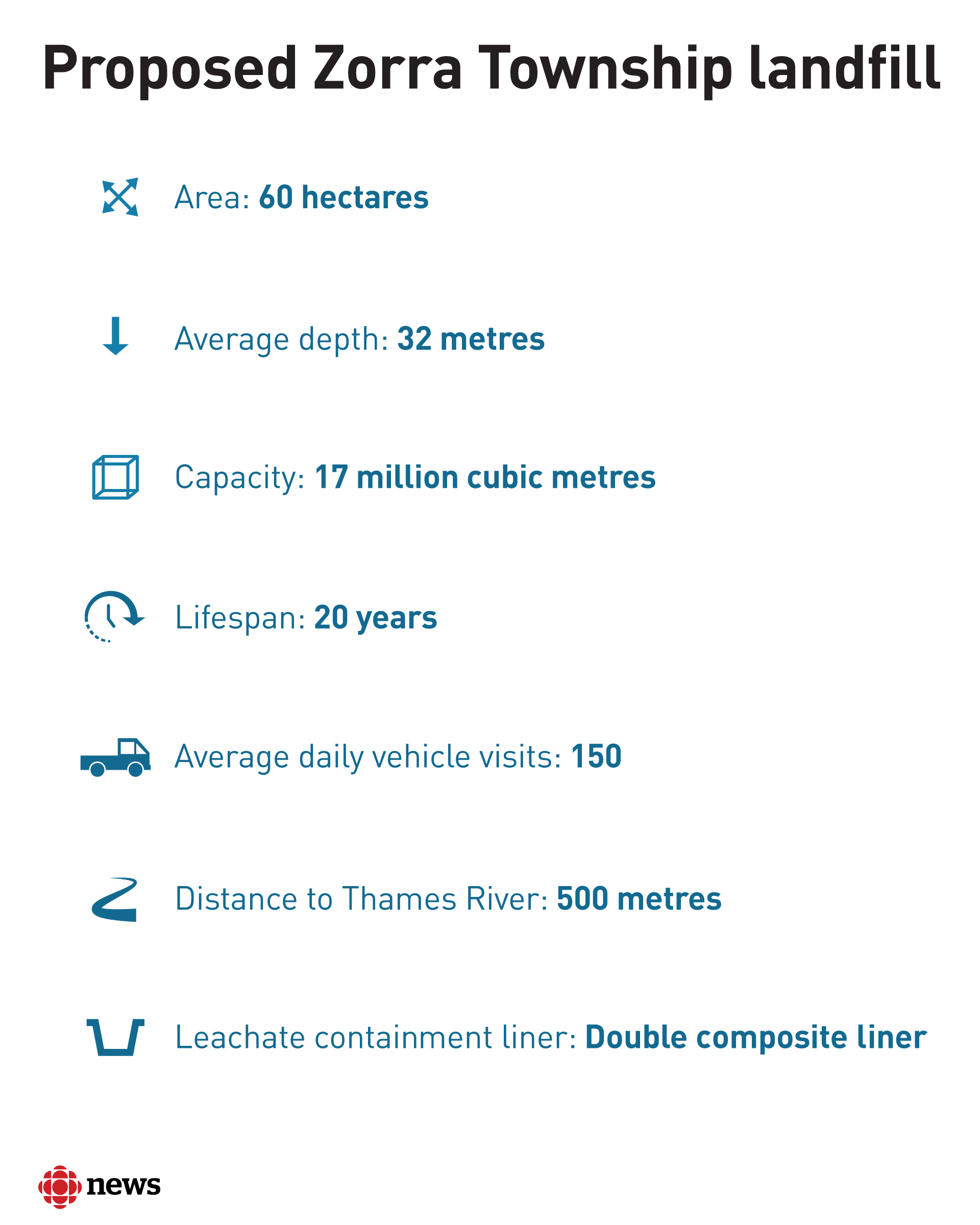

Though the opposition is centred in Ingersoll, the proposed landfill lies in the adjacent municipality of Zorra Township. The site is an operating limestone quarry owned by Carmeuse, an international lime conglomerate based in Belgium. Walker Environmental is proposing that the site be turned into a landfill that will take 17 million tonnes of non-hazardous household waste over a 20-year period.

Walker doesn't own the land, but the company plans to buy the site from Carmeuse if the dump gets green-lighted by the province.

In response to questions about groundwater, Walker points to the company's South Landfill, located in Niagara Falls, Ont. Opened in 2009, that dump has a 25-year life cycle while taking the same amount of trash annually as what's proposed for Zorra (850,000 tonnes).

Walker officials say the South Landfill site hasn't created a groundwater problem. But dump opponents say that's because the groundwater near the South Landfill isn't drinkable anyway.

The proposed landfill in Zorra occupies a 60-hectare footprint with an average depth below grade of 32 meters. It's less than two kilometres from downtown Ingersoll and close to the shores of the Thames River, which opponents argue makes the site a risky choice.

Their main fear is that leachate, the chemical stew of potentially toxic liquid formed when waste breaks down, will seep into their groundwater. Unlike nearby London, Ont., which draws its drinking water from two Great Lakes, the area relies on groundwater for drinking and irrigation.

The last line of defence

A landfill's containment liner is its main line of defence when it comes to keeping leachate out of the groundwater. Such liners are often described as working like a bathtub, with sides and a bottom both impermeable to liquid.

Darren Fry, a project director with Walker who's managing the landfill proposal, says the company plans to use the same heavy plastic containment liner as one that has been in use at South Landfill for years without incident.

The liner is part of a larger leachate containment system: a five-metre-thick series of barriers that include two plastic liners and pipes that can pump leachate to the surface, where it will be monitored and treated at an on-site wastewater facility.

But dump opponents remain concerned, saying it's likely the liner will break down and fail. They worry this failure could happen years after the dump is full and the containment liner is buried beneath tonnes of waste.

"We know that the liner is a sheet of plastic, and plastics break down when you put things through them," said Smith.

Fry, however, points to the double layer of leachate liners, combined with a monitoring system and series of drains that he says can be cleared, even after the dump has stopped taking new trash.

Diminishing dump space

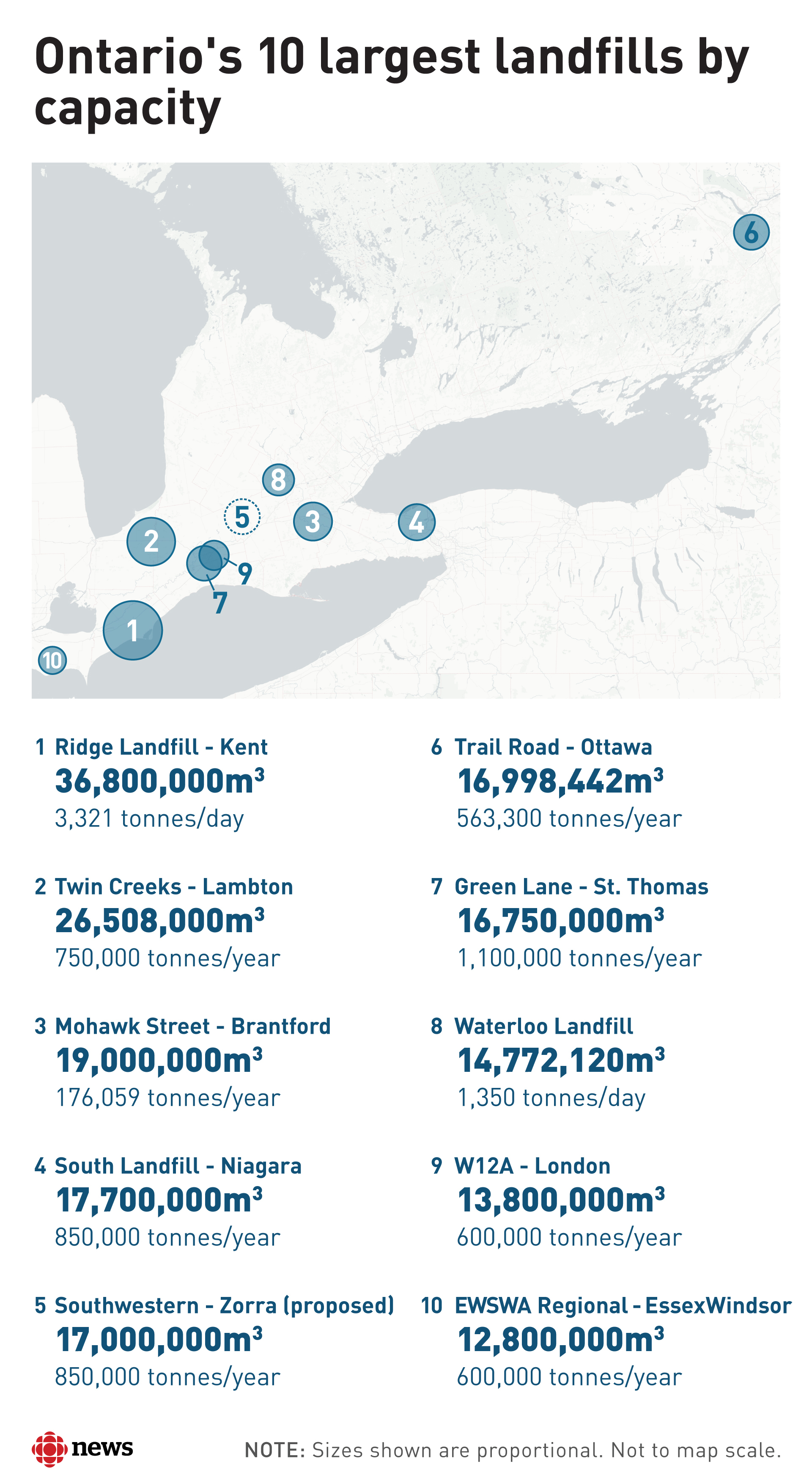

If approved, the landfill in Zorra township will be Ontario's fifth largest, based on capacity. But as large as it is, Fry points to industry research that suggests Ontario is running out of places to put its trash.

According to the Ontario Waste Management Association (OWMA), Ontario's available landfill capacity is expected to be exhausted in 10 to 14 years. Of the 8.1 million tonnes of waste the province landfilled in 2017, about 3.5 million tonnes was exported to the United States, mostly to Michigan.

"Ontario needs approximately 10 new large landfills in the next 10 years," said Fry. "Approvals take approximately 10 years to conduct. Ontario needs to expand existing sites and build new landfill sites."

It's easy to dismiss these as numbers produced by an industry that benefits by building more landfills, but the province is also sounding the alarm about landfill capacity in its environmental plan.

"Without reducing the amount of waste generated, it is forecasted that Ontario will need to site 16 new or expanded landfills by 2050," reads a line from the Ford government's environmental plan.

As the anti-dump signs indicate, landfill opponents are particularly irate at the idea of having big-city trash buried in their backyard. They see it as an unsettling trend: Big cities, unable or unwilling to deal with their own garbage, looking down Highway 401 for a convenient place to stash it.

In 2007, the City of Toronto bought the Green Lane Landfill, located a 30-minute drive south of London, near Highway 401. That landfill currently accepts about 500,000 tonnes of Toronto trash each year and is estimated to have capacity for another 20 years.

Walker says the proposed landfill in Zorra Township would accept non-hazardous household waste from across southern Ontario, including from areas in Oxford County, the regional municipality that includes Ingersoll and Zorra Township.

Fry pointed to a report that suggests even waste generated in Oxford County is being hauled away.

"The proposed landfill in Zorra would offer a local solution," he said in an email to CBC News.

Queen's Park response

The landfill proposal has created a challenge for the Ford government.

Ontario landfill applications undergo an exhaustive environmental assessment (EA) process with the environment minister eventually having the final say.

Fry said Walker is in the "final stages" of an EA process that started back in 2012. The company is expected to release a draft report before the fall that will include results from 12 different government-mandated studies about the project, looking at everything from traffic to water quality. A consultation period will follow, before a final EA is submitted to the minister, who can accept, refuse, or refer the application to a mediator or a tribunal.

But for Mayor Comiskey, the EA process has a glaring shortfall: It leaves municipalities with no say in the final decision.

Comiskey has led a push to give municipalities the right to approve or turn down any landfill application in their jurisdiction. So far, more than 100 Ontario municipalities have pledged support, with the complete list found on the Demand The Right website.

"It's common sense to say that if you have a municipality that is producing a phenomenal amount of garbage, they shouldn't be able to walk into another municipality and say, 'This is where we're going to bury it,'" said Comiskey. "They have to be responsible for what they produce and what they make. So we demand the right to say yes or no."

Comiskey, who describes himself as a small-c conservative, was encouraged by comments made by Premier Doug Ford during a visit to Oxford Country last March.

Ford was quoted on Heart FM's website as saying: "Who are a bunch of politicians in Queen's Park to tell municipalities how to run their municipality? It is up to them, they have an option, to opt in or opt out. That is up to them, it is not necessarily up to us to overrule a municipality. That is the last thing I would want to do. I don't care if someone says they have 300 or 400 jobs, we are not going to stick something in an area that people don't want."

While in Opposition, Progressive Conservative MPP for Oxford Ernie Hardeman twice launched a private member's bill that would give municipalities the right to turn down a landfill application within their borders.

"Municipalities have a right to decide where the Tim Hortons is built in their community; surely they should have the right to have a say in where a landfill would go,” he said in an interview with CBC News this week.

But during that interview, Hardeman fell short of backing an outright veto for municipalities over landfill applications.

Communities could voice their opposition as part of the tribunal process if an EA reached that stage, he said, and any legislative changes that go further than that are up to the environment minister.

In November, the Ford government released its Made-In-Ontario Environment Plan. On page 44, it promises to give municipalities "a say in landfill citing approvals" and to "enhance municipal say" in the process.

Comiskey says this isn't enough.

“We need the ability to say yes or no. Period," he said.

According to a statement from the office of newly appointed Environment Minister Jeff Yurek, the Ontario government plans to develop a proposal "to give municipalities more say" but it also doesn't mention a full veto.

"The proposal will balance the desire to give the people of Ontario a greater voice in the siting of landfills, while ensuring Ontario has sufficient landfill capacity for the management of our waste," the statement says.

As for Walker's Fry, he says granting municipalities a full veto could pose a problem amid diminishing dump capacities, as the EA process already takes up to 10 years.

Town braces for the decision

Back in Ingersoll, Donna Sexmith, a 70-year resident of the town, says she hopes the province dumps the entire proposal.

"There's gotta be better places to put it than the quarry," she said. "There's nobody that would want that dump here."

Bryan Smith says OPAL will continue to organize weekly flag-waving protests at various intersections throughout the area.

"We want a full-out rejection by the province on this dump," he said. "And then we want them to rethink what they're doing with waste all across the province."