April 4, 2018

It shook a community to its core.

Men disappeared from Toronto’s Gay Village. Many were last seen leaving the same gay bar.

They would be found dead — many killed in what appeared to be extreme violence.

People speculated a serial killer was at work, but police wouldn’t confirm their suspicions.

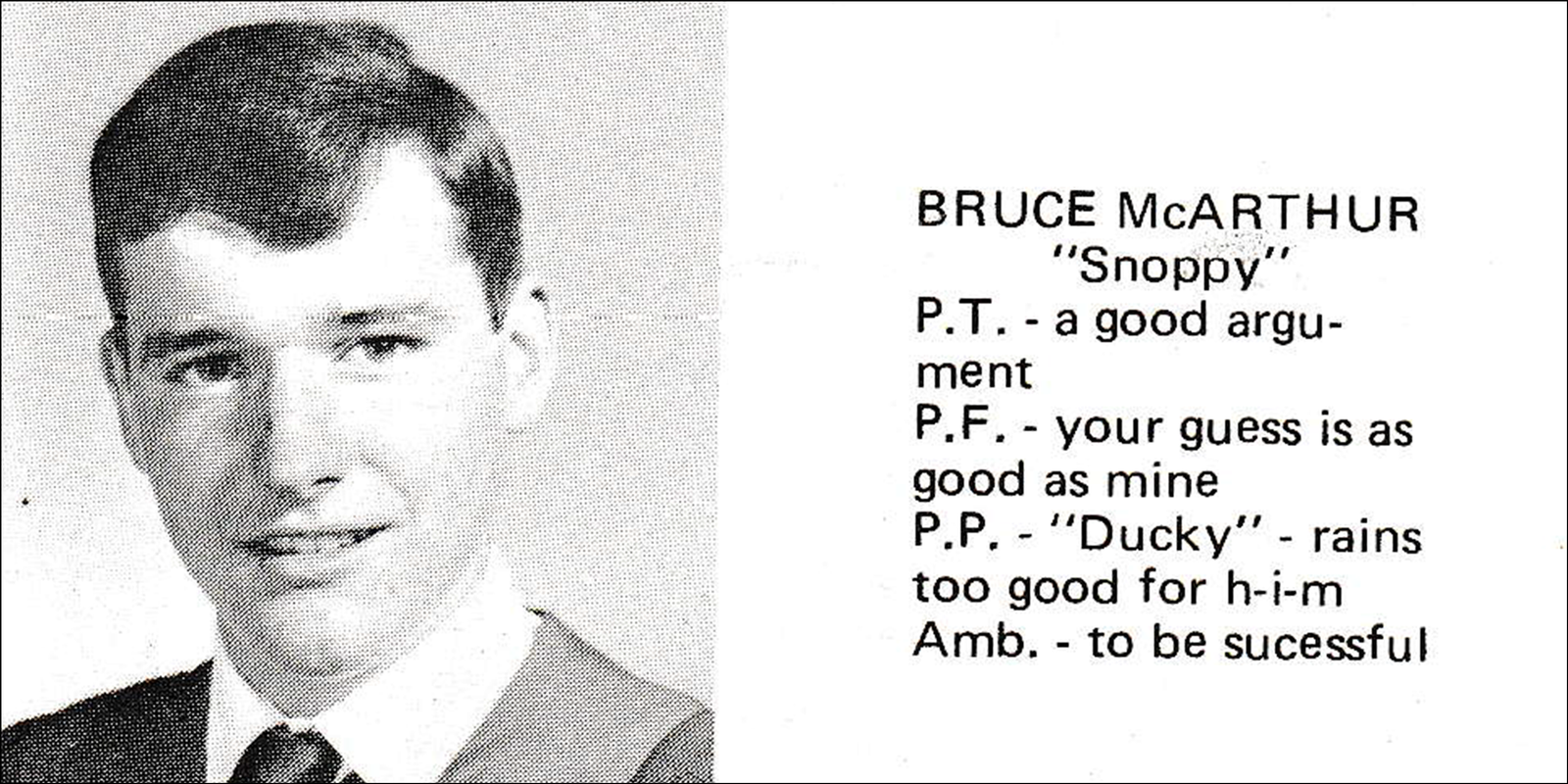

In January of this year, 66-year-old Bruce McArthur was arrested in Toronto. He’s been charged with six counts of first-degree murder — an alleged serial killer.

McArthur hasn’t entered a plea in the case.

But this isn’t the story of Bruce McArthur in 2018. It’s a story from the same gay community 40 years ago.

Between 1975 and 1978, 14 men from Toronto’s gay community would turn up dead. Half of those cases were solved and the others have gone cold. Many of the cases have striking similarities, leading people to believe the killings were connected.

During that time, McArthur was working in Toronto. He would have been in his 20s.

He hasn't been linked to any of those crimes, but Toronto Police Det.-Sgt. Hank Idsinga, the lead investigator in the current case, says police are looking into those mysterious disappearances four decades ago.

“We have pulled the cases from the 1970s that you’re talking about and we’re going through those with a fine-toothed comb to see if there are any links at all,” Idsinga told The Fifth Estate.

“Would it surprise me if Mr. McArthur was linked to some murders from his late 20s? It wouldn’t.”

It was the mid-1970s and John Foot remembers walking into the Eaton’s merchandise office on the 10th floor of a building on Downey’s Lane, a street that once existed under what is now the Eaton Centre in downtown Toronto.

On his first day there, he met a young McArthur.

“He was, like, a guy that was born with a smile on his face.”

Reports indicate McArthur started working at Eaton’s around 1973, when he was 22. Foot worked just a few cubicles from him.

“Everybody liked Bruce,” he says. “I can’t think of anybody who ever said anything against him.

“Bruce was always jolly and always fresh. Very jovial, very nice, very respectful, well-mannered.”

McArthur was a buyer's assistant for Eaton’s, a member of a department Foot describes as a pretty close working group. McArthur did mostly clerical work.

“He was a gentle, quiet, affable, good sense of humour kind of guy.… I would never, never ... have thought Bruce was capable of being a serial killer.”

Foot says McArthur never showed a single flash of anger — no temper, nothing of the sort.

McArthur and his then-wife, Janice, travelled to Europe in the late '70s. They stayed with Foot and his wife in London, England, for about two weeks on and off.

Not long after returning from their trip to Europe, McArthur was on to a new job.

He began working for Stanfield’s and McGregor hosiery, where he was again in a merchandising role — but this time he worked more autonomously and often travelled.

He would drive from town to town as a kind of sales rep — approaching department stores and getting them to stock his wares.

As the job expanded, McArthur needed help. He was getting so busy he needed “counters,” people who would stock and prepare the hosiery he was selling to stores.

The company wouldn’t confirm where McArthur’s route was, but reports indicate he worked around the Greater Toronto Area.

The "territory was probably from Durham right over through to Toronto,” says Pamela Bennett, whose mother was one of McArthur’s counters. “I remember going to Yorkdale [Mall] and to Sheridan Mall ... Cedarbrae, Scarborough Town Centre.”

“He was a really, really nice guy.”

Bennett’s mother and the other women who worked for McArthur often travelled to stores like Eaton’s and the Bay. She would often go along with her mother.

“We would go from store to store counting stock, bringing it out of the back room and then we’d fill up the racks. And then after that was done, we’d count everything, then we’d bring the counts back to Bruce and he would order stock according to our counts.”

She says McArthur was always friendly and thoughtful to the women who worked for him.

“They would meet and have, you know, dinner or something [in] downtown Toronto, and at Christmastime he would give gifts to them for their work.

“He was a really, really nice guy.”

Bennett remembers he bought her mother Dickens’ Village figurines — miniature porcelain houses that ranged from about $50 to $100 each.

They were collectors’ items that would make up a Christmas village. Eventually, Bennett says her mother had enough figurines from McArthur to create her own village.

McArthur, too, had a collection she says he displayed “proudly” year-round.

“It would probably take up a 10-foot by four-foot table at least.”

Much like Foot, Bennett says she was shocked when she heard about McArthur’s arrest. So shocked, in fact, that she, too, thought it was a mistake.

“At first, when the first two murders came out, we just said, ‘No, they’ve got the wrong person, it can’t possibly be Bruce.’ It just didn’t make any sense.

“We literally almost fell off the couch when we saw that news report that night,” her husband Bruce Bennett says.

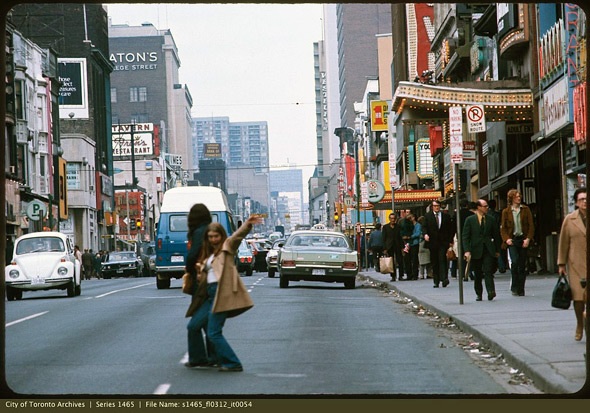

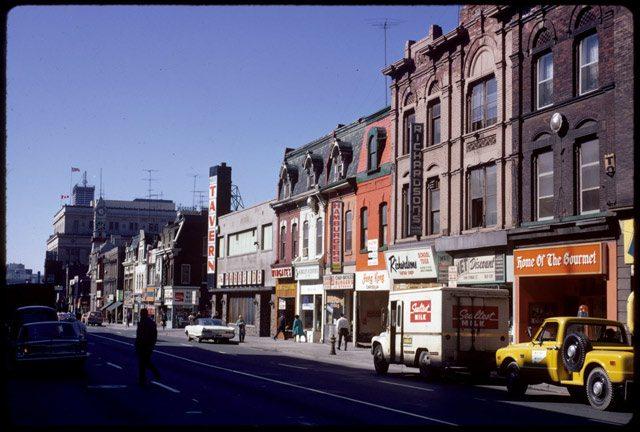

More than four decades ago, Toronto was a vibrant, thriving community and young people from all over the country were flocking to the big city.

A young Bruce McArthur was working at Eaton’s downtown.

Slowly over those years, a fear began to take hold in the gay community as men began vanishing.

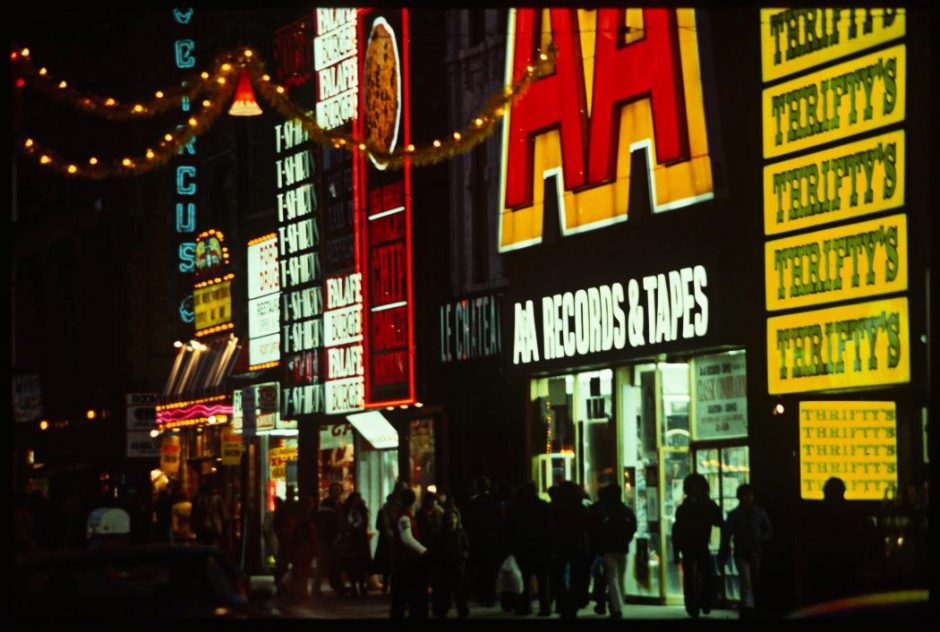

At that time, the Gay Village was a small stretch of Yonge Street between College and Wellesley streets, anchored on either end by two bars — the St. Charles Tavern at the south end and the Parkside Tavern at the north.

Rev. Brent Hawkes remembers the time well.

With few places for gay people to feel safe, the community would flock to bars, primarily in that area.

“They were usually dark and dirty and dingy places,” says Hawkes.

He moved to Toronto from his small town of Bath, N.B., to “find his people” — that is, to move to the big city where there was a larger gay community.

Hawkes became a member of the Metropolitan Community Church, which was a place for members of the gay community to come together and practise their faith.

“People need to remember in the mid-’70s this was only a few years after same sex adult sexual behaviour was decriminalized in Canada,” he says, noting that had happened in 1969.

TIMELINE |Same-sex rights in Canada

“Psychiatrists said we were sick,” Hawkes says.

“There were no human rights protections…. Lots of people [were] fired from their jobs simply because they were gay or rumoured to be gay.”

Gay people, Hawkes says, were regularly kicked out of their apartment buildings and were denied public services.

“People were really afraid of being open and talking about their private lives.”

Hawkes remembers telling people to leave the bars in groups because otherwise you’d risk having “gay bashers beat you up, and you don’t want to have the police beat you up.”

This led to increasing tensions between the gay community and police that would only worsen as men started to disappear from the community.

“People were talking and people were afraid,” Hawkes says. “Many people knew people that were murdered and [were] afraid and ... absolutely believing that there was a serial killer.”

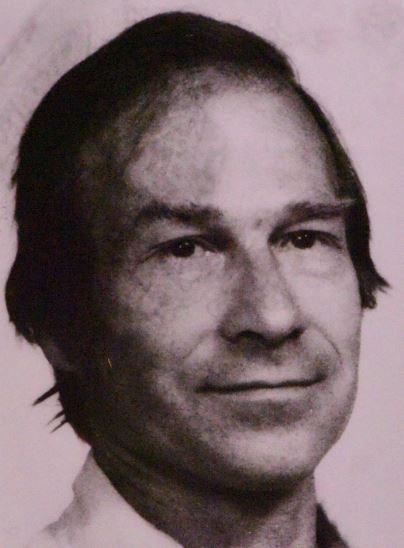

It was a balmy Friday in downtown Toronto in mid-January 1977 and Brian Latocki left work a little early.

The 25-year-old financial planner from Winnipeg told co-workers at the Toronto-Dominion Bank corporate headquarters that he felt ill.

He was last seen much later in the evening of Jan. 21 leaving the St. Charles Tavern, one of Toronto’s most popular gay bars and a location that would become a commonality in at least four of the 14 homicides of gay men in that decade.

When he didn’t show up to work the following Tuesday, Latocki’s boss called the superintendent of his apartment building on Erskine Avenue, near the Yonge and Eglinton neighbourhood in Toronto.

When police arrived that morning, they found Latocki tied to a bed. He had been tortured, strangled and stabbed to death.

There was blood splattered on the bedroom’s floors and walls. His head had been badly beaten.

Latocki’s apartment had also been looted.

The autopsy revealed that he had died three days before — sometime on the Saturday after he was last seen.

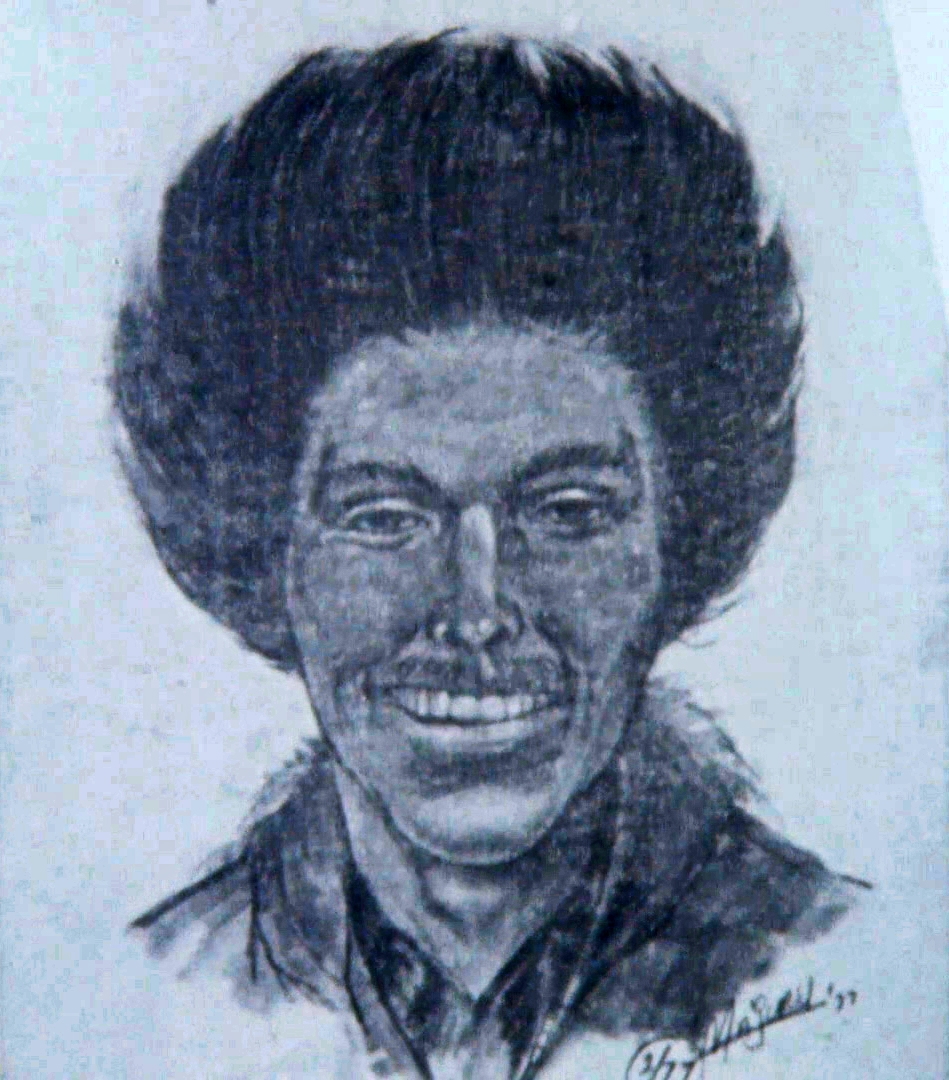

At the time, police said robbery was the motive. They released a composite drawing of an East or West Indian man, aged 25 to 27, with thin features and a medium brown complexion. He was spotted leaving the St. Charles Tavern with Latocki that Friday night and allegedly offered to drive him home.

Police posted a $10,000 reward for any leads.

A month earlier, Latocki had been enjoying Christmas Eve in Winnipeg with his family. They made the point to get together every Dec. 24 for Ukrainian food.

His cousin, Nancy Latocki, who was three years older, remembers teasing Brian at that get-together about his three-piece “banker” suit.

“His wardrobe certainly changed after he went to Toronto,” she says. “He looked much more professional.”

Nancy says Brian was more like a brother than a cousin.

His mother had died at an early age and they saw each other at least once a week when they were younger. They celebrated birthdays, took trips together to visit family in California and spent time during the summer swimming.

Nancy says as a young boy and as a teenager, Brian was engaging — someone you wanted to spend time with.

“Everybody liked him,” she says. “He was funny. He was interested in everything.”

The cousins grew up in the era of the British Invasion, and Nancy recalls being a Beatle-crazy teenager. At the age of 14, she and her twin sister were at home recovering from spinal surgeries when an excited Brian called.

“He found out that the Beatles’ airplane was going to be landing in Winnipeg — for some reason, it got diverted — and we were such Beatle fans.

“He just got so excited he said, ‘Can you phone for an ambulance? I’m sure that you could come out to the airport and they’d let the ambulance come out on the tarmac so that you could meet the Beatles,’” she says.

“That’s the funniest recollection that I have.”

Nancy says Brian was inquisitive and intelligent. He attended the University of Manitoba's faculty of commerce in the early '70s.

Brian graduated in 1974 and got a job in Winnipeg with the Toronto-Dominion Bank before landing a position in Toronto.

“He really liked his job,” Nancy says. “He liked … the climate of Toronto.”

Looking back at family photos of Brian brings back the painful reminder that her cousin is gone.

“You look at him and he’s in his prime, he’s just getting ready to go out into the workforce and … start a career, and he was excited to do that.”

Nancy says she won’t soon forget just how quickly his life — and her life with him — was swept away.

“That was totally traumatic.”

She was arriving home from work when her mother, who was in the kitchen making supper, said she had bad news about Brian.

“It was just too hard to even grasp…. And we didn’t really have very many details,” Nancy says, noting they learned a lot through newspaper clippings sent by a relative in Toronto.

“The fact that he had been strangled and stabbed, it was just incomprehensible. And it was … just very, very hard to believe that that had happened to him, and why someone would do that to him,” she says.

“You read about it, you see it in movies, but never in your life would you ever think that something like that would happen to someone that you love.… And he was loved.”

Reports at the time described Latocki as shy and new on the gay scene in Toronto.

Nancy says the family didn’t know Brian was gay until they read about it in the newspaper clippings.

“Back in the '70s, people didn’t really talk about it…. It carried a stigma at that time,” she says.

“That would not be something that you would feel that you could come out and say that that was your inclination. Not at all.”

Nancy says things changed after Brian was killed. The family “never really talked about it much after,” she says. “I think it tore them apart.”

Forty years later, she still tears up while thinking about Brian.

Over time, she has learned to cope with the loss, but she’s still left to wonder what happened to him on that January night.

“For me, well, you always hope that you would find out, because it was such a big question mark — how this even happened and why. And why someone would want to kill him,” she says.

“I don’t think we’re ever going to know.”

Latocki’s death wasn’t the only brutal killing of a gay man in the '70s that would leave unanswered questions.

Two years before Latocki’s death, on Feb. 18, 1975, 52-year-old Arthur Harold Walkley was stabbed in a house on Borden Street, about two kilometres from the Gay Village, where he was last seen.

It would be the beginning of a series of 14 homicides of gay men over the next four years.

In the early morning hours that Tuesday, Walkley’s roommate found him covered in blood, naked and stabbed in the back and chest.

Police arrived around 4 a.m. Walkley died shortly after arriving at hospital. His apartment was ransacked and credit cards were stolen. No knife was found.

A month later, police posted a $2,000 reward for any information.

News reports say Walkley was last seen leaving a tavern on that stretch of Yonge Street with an unidentified man around 2 a.m., and that police were looking for the cab driver who may have driven him home.

Police turned up no suspects in the case.

Walkley, a University of Toronto lecturer and community activist, was known to friends and students as Hal. In his earlier years, he taught history at a high school in Etobicoke, west of Toronto.

One of Walkley’s students from Vincent Massey Collegiate Institute (VMCI) has only the fondest memories of his teacher.

“I was heartbroken [when I heard],” former student and retired Toronto police officer Lou Hagerman says. "I'm dyslexic and struggled with school. If Mr. Walkey hadn't talked me out of dropping out, I wouldn't have had the honour and privilege of being a Toronto police officer for 35 years. I owe a lot to him."

Hagerman was working when Walkley was killed and says he made “all sorts of inquiries” into the death of his teacher.

Now, in light of McArthur's arrest, Walkley’s death has new meaning for the former police officer.

“Since this all happened with the Gay Village thing, I’ve thought about Hal Walkley a lot."

That community was about to be shaken only 10 months after Walkley’s death when another man was found brutally killed.

On a mid-December evening in 1975, Fred Fontaine was found after a vicious assault in the washroom of the St. Charles Tavern.

Officers found the 32-year-old CBC technician suffering from blunt force trauma. He was taken to hospital and was in a coma until his death seven months later.

Nearly a year after Fontaine's assault, in the fall of 1976, James Kennedy was found dead inside his Jarvis Street apartment, just blocks from the neighbouring gay hangouts.

The 59-year-old worked in the Department of National Revenue on Adelaide Street in downtown Toronto.

He, like at least four of the others, was last seen leaving the St. Charles Tavern on Yonge Street not long before his death.

He was found dead on Sept. 20, naked and with his face badly beaten. He had been strangled with a towel.

Two years later to the day — Sept. 20, 1978 — police were called to yet another grisly scene: the killing of Alexander (Sandy) LeBlanc, the manager of the Studio II discotheque at Church and Carlton streets and a well-known member of Toronto’s gay community.

David Penny, a former constable with Toronto Police's 52 Division, was one of the first officers to arrive. It was his first homicide case.

"I can picture the scene right now," says Penny. "That one was particularly brutal."

LeBlanc, 29, was stabbed more than 100 times from head to foot.

Alexander (Sandy) LeBlanc was found dead in his St. Joseph Street apartment in September 1978, in a spate of killings of gay men in the '70s in Toronto.

LeBlanc’s friends hadn’t heard from him. Worried for his safety, they kicked in the door at his St. Joseph Street apartment. They found LeBlanc’s blood-spattered body on the floor.

“As police walked around the body, the carpet squished from the sound of absorbed blood and bloody footprints led to an open window,” journalist Robin Hardy wrote in the Body Politic in 1979.

It’s a scene Penny will never forget. "There was a heck of a lot of blood,” he says. “He must have fought for his life."

Despite all the evidence — semen on the bed and blood everywhere, as Penny recalls — there were limitations to what the police could investigate.

"We had limited suspects without DNA," says Penny. "Whoever did it, it was really, really violent."

In late November 1978, Duncan Robinson was found dead in his bedroom on Vaughan Road near Bathurst Street and St. Clair Avenue.

His sister made the call to police after Robinson didn’t show up to his work for two days.

Robinson had multiple stab wounds to his chest and his body had been badly mutilated.

At the time, police said they believed the 25-year-old left the St. Charles Tavern with another man around 2 a.m. the night before. They believed that man to be the killer.

The man was described as between 27 and 30 years old, six feet five inches to six feet seven inches tall, with a lanky build, greasy brown hair, a scruffy goatee, sloping shoulders and dirty hands.

A neighbour reported hearing a “peculiar loud hollow noise” coming from Robinson’s apartment that night around 9 p.m. Another neighbour reported loud music coming from his apartment a few hours later.

In late November 1978, Duncan Robinson was found dead in his bedroom on Vaughan Road near Bathurst Street and St. Clair Avenue.

Police also found blood samples at the time that indicated the killer had been injured.

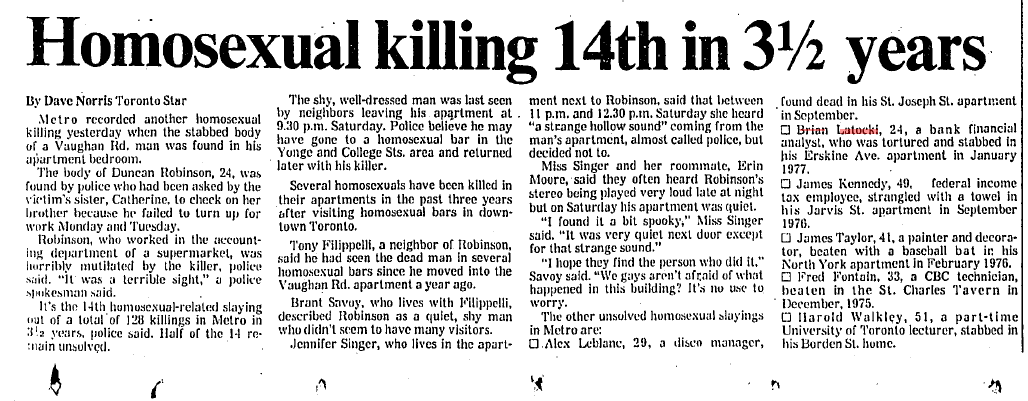

News reports in 1978 noted 14 of what were called “homosexual” killings in 3 1/2 years, including cases of men who were left naked, tied to beds, stabbed or beaten to death and with their apartments ransacked.

The cases presented some similarities: many of the men were last seen leaving the St. Charles Tavern, most were found in their homes, stabbed or killed by blunt force trauma in a manner police call “overkill,” and they were all members of the gay community.

Despite the seeming connections, Penny doesn't know why the brutal and violent deaths weren't considered serial killings.

"That's a good question because there were a lot of murders in the homosexual community," he says.

"We investigated Sandy's murder as vehemently as we would have anybody's. There was no prejudice that way. You wanted to get the bad guy."

Penny says a lot of uniformed officers at that time “wouldn’t have anything to do with that community and vice versa.”

"It wasn't adversarial, but it was the '70s," he says. "I'm sure there was some sort of prejudice, if you want to use that word, but that's just the way it was."

Hawkes says there was a sense of helplessness in the gay community at the time.

“I think it was a more paralyzing fear than today’s motivating anger,” he says.

“Back then, there may have been people who might have had a sense of what was going on but who didn’t go to the police, and didn’t report it.”

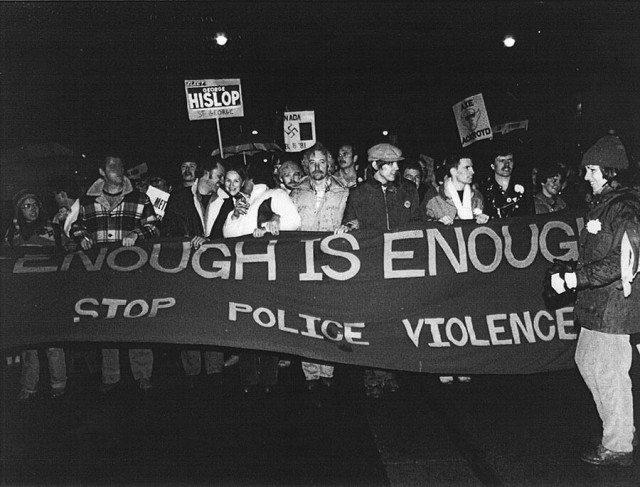

Tensions between police and the gay community in Toronto escalated, coming to a head during the bathhouse raids in 1981, when more than 250 gay men were arrested in four bathhouses in one night.

“[Police] tore them apart, tore doors down, tore lockers apart,” Hawkes says.

He says the relationship between police and the gay community is improving, but not for everyone.

“We’ve made huge progress, substantial progress with the police, but predominantly with the white gay community. There’s still a lot of work with marginalized racialized groups. We’re not there.”

Hawkes doesn’t look at the present situation with despair, but instead thinks about how things can change moving forward.

As people in the community reflect on the horrors of today, they can’t help but think back to the last time this same fear stalked the gay community.

“We need to say, ‘What can we learn from this? How can be we be better in this?’ And insist on that,” Hawkes says. “Then maybe people won’t have died in vain.”

Watch The Fifth Estate's Murder in the Village: Bruce McArthur and the Mysterious Deaths in the 1970s, Friday at 9 p.m.