December 21, 2018

Alex Hall was sleeping in his tent when a rumble in the distance pulled him from his slumber.

It was 4 a.m., on July 21, 1978, and the midnight sun was already out.

The avid outdoorsman was camping in the middle of one of the most remote wilderness areas remaining in Canada — the Thelon Wildlife Sanctuary.

Crawling out of his tent, he could hear them before he saw them — the deafening drone of cries and thuds engulfed the air around him from miles away.

Then, the masses arrived.

Caribou cows and calves were packed shoulder to shoulder, protecting each other from ravenous insects.

“You could see tens of thousands of caribou at any given second," said Hall, who said herd after herd passed in a never-ending cycle for the next 27 hours.

“I could almost reach out and touch them.”

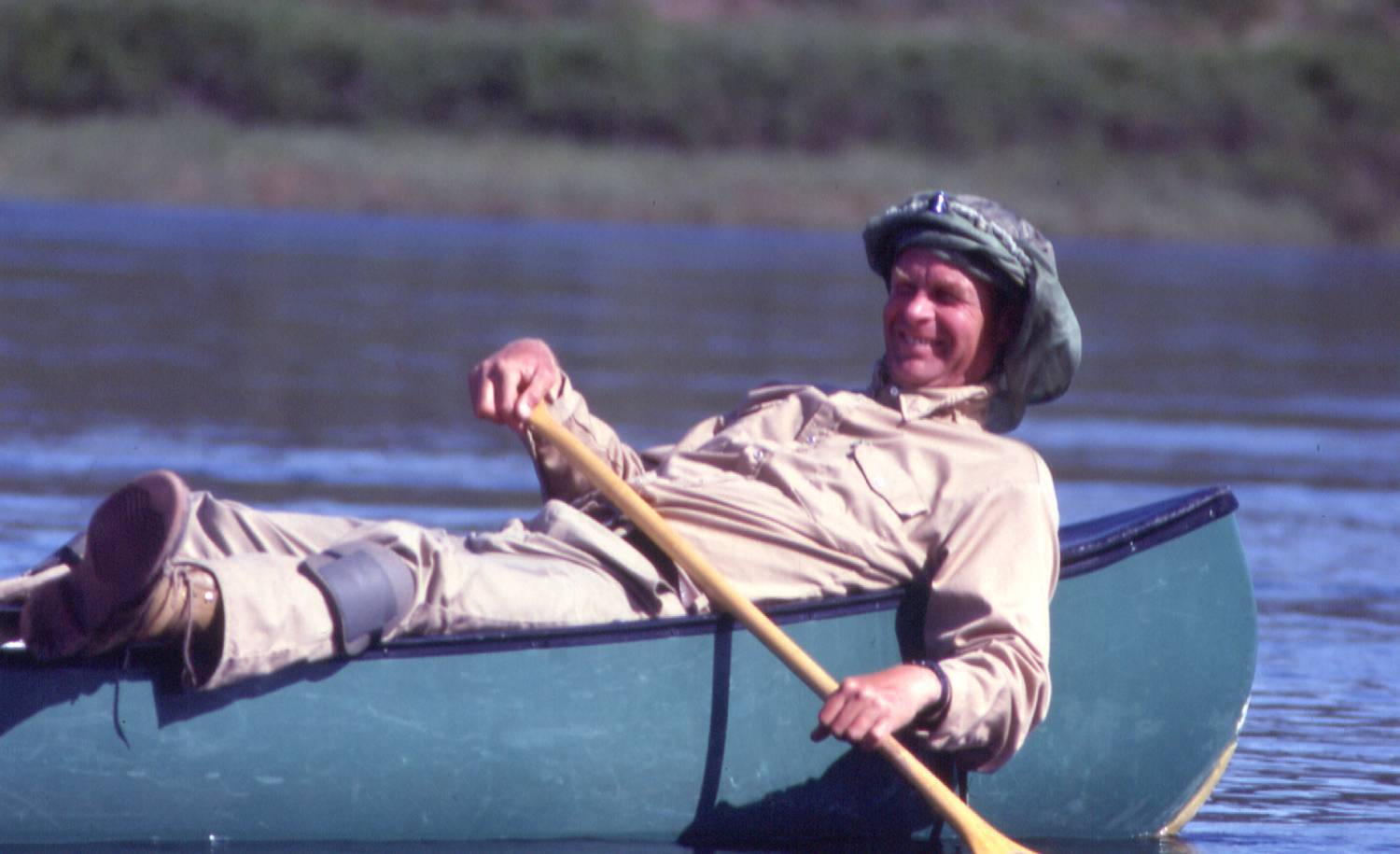

This is just one of many moments Hall holds dear from his 46 years paddling the Thelon River.

Since 1975, Hall was one of the only tour operators in the world to take people to this place he calls "paradise" — an oasis, tucked away in Canada’s North.

This year, the 76-year-old from Fort Smith, N.W.T., learned he may never return to the Thelon. Doctors found a tumour between his kidney and bladder, which had spread to his spine.

In April, they told him he had about a year to live.

Hall’s one-man business, Canoe Arctic Inc., which he ran for nearly half a century, was about to close up forever this spring. But in a “serendipitous” turn of events this year, Hall found a young man with just as much fervour for the waters as he has, who would take over his tours for one last season.

The place where God began

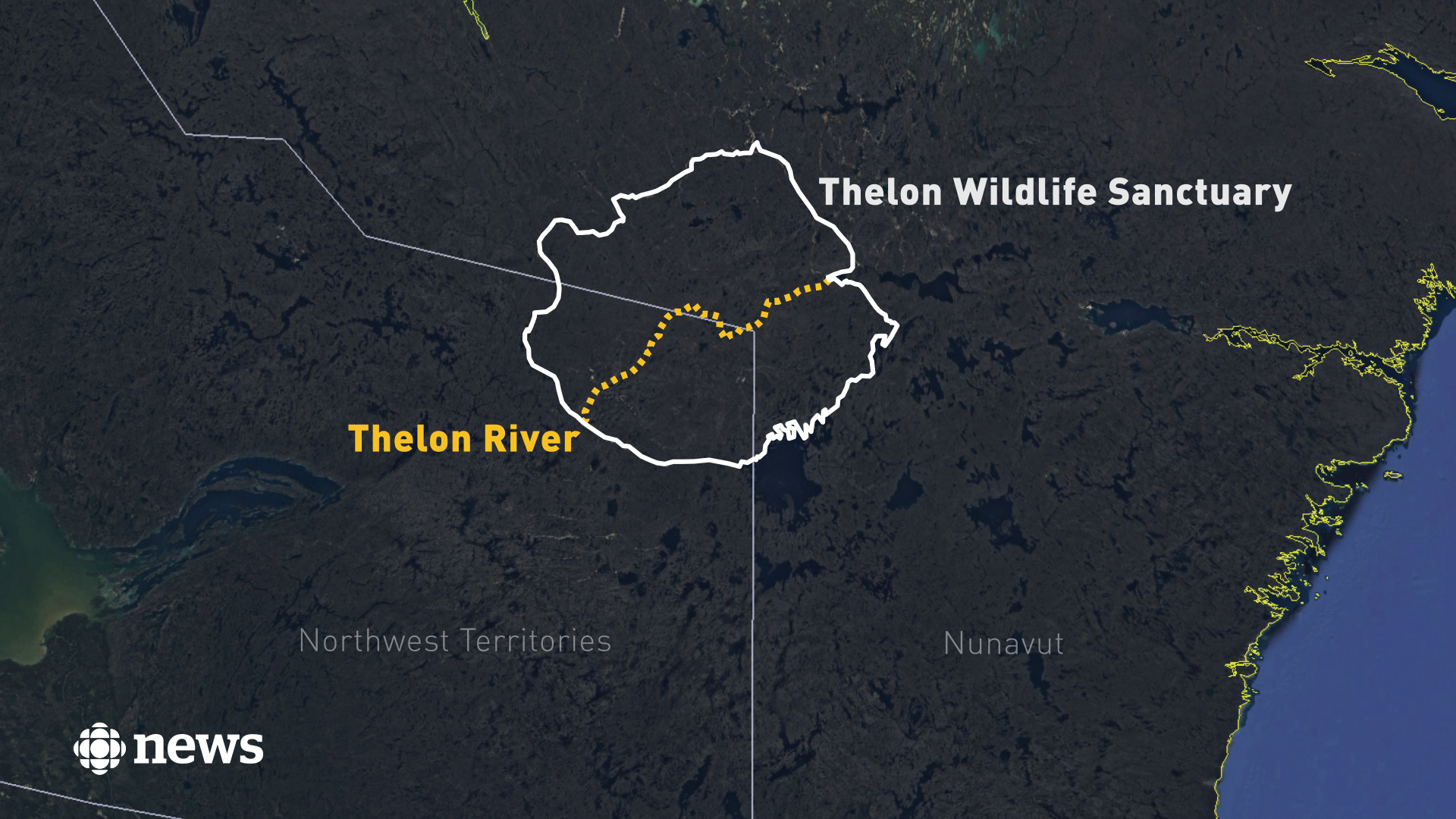

At more than 900 kilometres long, the Thelon River is the largest river in the Canadian tundra. One of its major sources is Whitefish Lake, east of Great Slave Lake in the N.W.T.

Hall said it's actually more than 1,200 kilometres long with all the headwater lakes.

"I've measured it," he said chuckling.

"It was Eden, you know."

Along the river is the Thelon Wildlife Sanctuary, established in 1927. It's the largest protected area in Canada. At about 52,000 square kilometres, the sanctuary sits at the border of the N.W.T. and Nunavut. The Barren Lands are considered one of the largest remote wilderness areas remaining in North America, and even the world, according to multiple government of Nunavut reports and an N.W.T. environmental review board report.

Indigenous groups in the territory describe the area as “the place where God began.”

It was the place Hall fell in love with, mainly for its unparalleled wildlife.

Large mammals such as grizzlies, wolves and muskox, and smaller animals like porcupines, otters and tundra birds once littered the place, he said.

Hall said there are hundreds of thousands of lakes, nearly all of which do not have names.

“You feel totally diminished. You’re just a tiny insignificant speck,” said Hall.

“It was Eden, you know.”

Tundra covered in caribou

Hall’s love for wildlife budded as a toddler in Brampton, Ont., where his father — an avid hunter and fisher — would take him out on the land.

It was through one of his dad’s wilderness magazines where Hall first learned about the Thelon.

In 1970, the young Hall was finishing up his thesis when his professor asked a group of students to Nunavut’s Barren Lands for a wolf and caribou study.

It was this trip that fostered his love affair with the North.

As the small Cessna-180 broke through the clouds, Hall saw the lush green tundra covered in white-coated caribou and snow geese.

The memory still draws tears from his eyes.

“I was hooked for the rest of my life."

Hall became a desk-job biologist in Ottawa, but he couldn't stop dreaming of the North.

It took about a year for him to return, this time on a 37-day canoe trip on the Thelon River.

In 1975, Hall took his first client to the Thelon. The next year, he took one more. His full-time business really took off in 1977, eventually garnering clients from around the world.

“This guy is just this walking encyclopedia,” said Josh Tordiff, a family friend.

What Hall doesn’t keep in his head, he documents and stewards throughout his home: 41 pages of topographical maps stored in a basement cupboard; 46 summers’ worth of diaries, with tips on how to “relieve oneself in the woods” and “why one shouldn’t touch wolf excrement”; meticulous notes on archaeological sites and ancient arrowheads; dozens of framed photographs of wildlife in stacked, stuffed boxes; and weathered animal remains scatter his home and garage.

“He’s the most interesting man in the world, but it’s like a secret,” said Tordiff.

“He knows the history of the area better than anyone alive,” said Kevin Antoniak, Hall’s best friend.

Hall gets lost in buildings, but he’s a human GPS in the wild, his loved ones say.

Geneviève Côté, who’s known Hall for 12 years, remembers him as being father-like on the trips.

He'd cook every meal for his clients with his arms covered in layers of black flies and even fought away black bears under the midnight sun, with only his underwear on. (He has scars to prove it.)

“Every summer, all summer long, he’s been sharing [the Barren Lands] with people,” said Côté.

“I think it’s his greatest legacy.”

Antoniak said Hall became an outfitter not for the money, but so that he could be in the Barren Lands every summer.

“He’s probably more worried about not paddling the Thelon than dying."

A relationship blooms

Hall describes his cancer diagnosis as the "end of life as I knew it."

By July, Hall had severe vertigo, extreme fatigue and his sight started wavering. His taste buds also took a hit thanks to chemotherapy.

“Life’s pretty crummy,” said Hall, chuckling.

Hall was active enough to do solo paddling trips to the Barren Lands up until a year ago. Now, he hates walking down the street. People think he’s drunk because he wobbles so much, he said.

Immediately after the news of his cancer, Hall prepared to fold up his business. No one he knew could take over what he’s built over nearly half a century.

He began calling clients for his already fully booked 2018 and 2019 tours. It was a big financial hit to refund those tours, he said.

Then one day, Hall said he heard a radio story on CBC about a young paddler struggling to start his paddling business in the Nahanni River.

Hall said Dan Wong’s fervour for paddling and determination for starting his business reminded him of himself; he too, was in his 30s, when he struggled to start his business.

Wong, operator of Jack Pine Paddle, grew up in Yellowknife and has guided extensively on rivers in the Mackenzie Mountains and the East Arm of Great Slave Lake. He’s an advanced instructor from Paddle Canada, a national paddling certification body.

Hall got in touch with Wong and said the two “hit it off.”

They still meet whenever Hall is in Yellowknife for chemotherapy. Now they call each other mentor and mentee.

"The man is a legend,” said Wong, who’s been learning as much as he can about the Thelon from Hall.

“I’ve spent about a decade just paddling on my own,” said Wong, enthusiastic about another similarity between him and his mentor.

“Alex did the same thing. He spent a few summers just exploring.”

Hall's tour operator's licence for the Thelon sanctuary has been transferred to Wong. Now, Wong's preparing to take 39 of Hall's 2019 clients there next summer.

The two will share the profit made from that tour.

“It’s a love story.”

This summer, Hall sold some of his canoes to his mentee. Wong visited Hall again, during Thanksgiving, and transcribed each of Hall’s maps before they eventually go off to Yellowknife's Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre for archiving.

“He knows every nuance, every artifact, all the best campsites, the best fishing spots, he has the rapids memorized. The wealth of his knowledge is great. He stands alone,” said Wong.

“It’s a love story.”

A disease to cry for

Hall never once gets emotional talking about the most devastating news of his life — the cancer that snatched him away from his beloved Thelon.

Instead, he chokes up about the disease in the Barren Lands.

“The caribou are gone. The wolves are gone with them,” he said.

The last caribou herd he saw was in 2003. He said he hasn’t seen a single caribou in the past three years.

In 1992, he counted about 464 muskox in a five-week period. “Today, you’d be lucky to see any,” he said. “Nothing. It’s an empty land.”

Hall said it may be because of development, mining, and roads.

“That’s what’s going to kill it all in the end,” he sighed.

Hall said he saw the best of it. The next thing he said was barely a whisper.

“When we had the big populations of caribou, wolves ... I don’t know if they’ll ever come back or not.”

After a long pause, Hall said he longs for one thing.

He said he’s optimistic.

“I hope the animals return.”

Hall's loved ones organized a short trip in September to take Hall to see his most favourite place in the world, one last time.

In November, Hall said in an email his cancer stopped growing in his spine, and the tumour between his kidney and bladder seemed to have disappeared after 18 weeks of chemotherapy.

Mid-December, Hall emailed CBC and said his cancer was in remission.

Update: Alex Hall died on March 2, 2019, in Fort Smith.

This story is a part of a CBC series called Tour Territory. Do you have a tourism related story in the N.W.T.? Contact priscilla.hwang@cbc.ca