March 11, 2019

First you hear the giggles. Then a pair of skinny legs appear, precariously balanced on a wooden patio railing.

The girl is wearing just a T-shirt and a hastily added tuque and pink wool scarf.

She hurls her body off the edge and into the deep snow. The eruption of laughter and powder is a quintessential Canadian childhood moment.

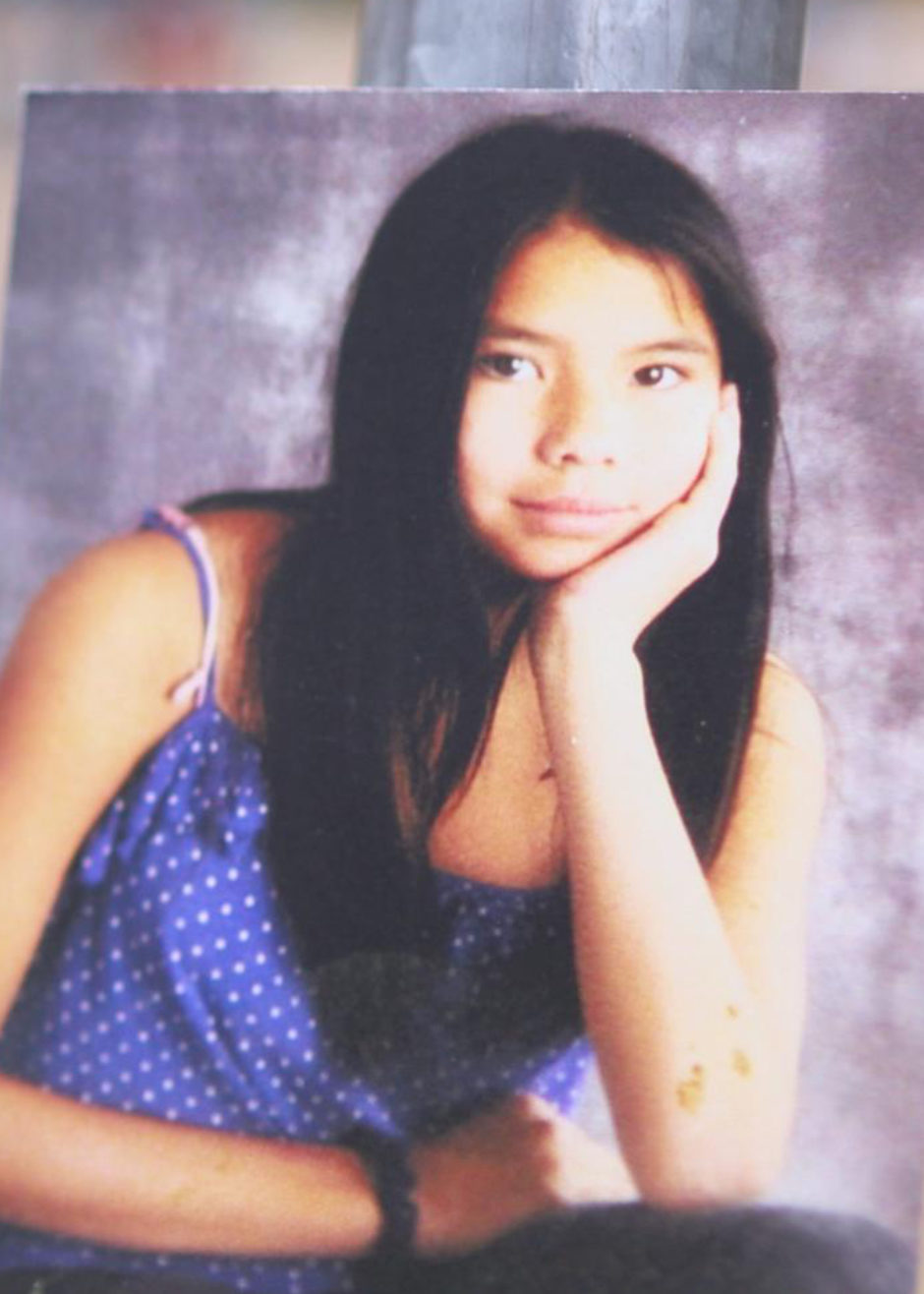

This is the Tina Fontaine her great-aunt Thelma Favel remembers.

Tina Fontaine's giggles reveal the happy little girl Thelma Favel remembers.

"She was really outgoing, lovable — really, really big heart."

Favel says she doesn't recognize the girl in the photos from the last month and a half of Tina's life.

"The stories that I heard, that doesn't sound like Tina at all — that's not the Tina I knew."

Those photos were taken during a weeks-long descent into addiction and exploitation after a visit with Tina's biological mother went horribly wrong in the summer of 2014.

On Aug. 17, 2014, Tina's body, wrapped in a duvet and weighted down with rocks, was pulled from the Red River. No one has ever been convicted of a crime in connection with her disappearance and death.

But the discovery of her tiny body shattered a nation and catapulted her to the front pages as the poster child for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

In death, Tina ignited a fire in the wider community that burns today with determination not to let it happen again.

Change

Alexia Légère gently spoons pink chunks of ham onto slices of bread. She carefully wraps the sandwiches in cellophane, as though they are precious offerings.

To her, they are.

The 30-year-old mother of five hands them out during evening walks with the Mama Bear Clan through one of Winnipeg's poorest neighbourhoods.

These sandwiches aren't just about filling empty stomachs. They are about giving people at risk of being exploited the chance to say no — even if it's just for one night.

Légère knows first-hand how important that is. She's lived it.

"In my situation, there was a lot of older men that took advantage of me not having anything, because I didn't have food, I didn't have money. So they prey on girls, which is really horrible, and they prey on mostly Aboriginal girls," Légère says.

Légère was just 14 when she ran away. She says she was addicted to crack and "anything she could get her hands on."

"There's a lot of people that will single out young girls because they know that if they provide them with money or with different items that the girls will do things that they probably wouldn't do if they weren't on the street, if they weren't vulnerable.

"You pretty much do what you have to do to survive," Légère says.

"I was lucky. I got out, but a lot of people don't."

'It's triggering, but I need to help them'

Of all the unlucky souls on these streets, one in particular inspired her to take action: Tina Fontaine. Légère sees a lot of herself in the young girl and feels a deep loss when it comes to the future Tina never got.

"I just wish she could have lived the life that she should have. Like, she had dreams, she had goals, and everything was taken from her," Légère says.

"Just because she was out here," Légère nods her head to the street, "and she was in care, like, she still had a chance. She still could have made it…. I felt like she just got stripped of everything."

Walking with the Mama Bear Clan helps Légère come to terms not just with her grief over a teen she never knew, but with her own pain.

"We have women that are being abused on the street and they see us and they run to us. It's triggering, but I need to help them," she says, her voice quivering but still resonating with conviction. "That heals my soul from all the trauma that I've experienced."

15 candles

Thelma Favel has fostered 67 kids. They all smile down on her from the walls of her living room in Powerview, about 100 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg.

She doesn't remember just their names, but every single birthday as well.

Granted, Tina's birthday isn't all that hard to remember: she was a New Year's baby.

Every year on Jan. 1, Favel has a birthday cake for her.

There are always 15 candles on Tina's cake. The number of candles, like the portraits of her on the walls, are frozen in time.

'She wanted everybody to feel safe'

Tina was just four when she and her sister came to live with Thelma and her husband.

"When I first got those two little girls, they came with one bag and the clothes that they had on and one T-shirt between the two of them," Favel says.

Favel remembers Tina as a spirited and mostly happy kid.

"Oh, she'd get into her little mischief moods, but other than that, she was perfect. The way I see it, anyway."

Videos of Tina shared by her family with CBC News reveal a fun-loving girl, quick to laugh. In others she records sweet, thoughtful missives to friends.

Tina also took less popular and bullied kids under her wing, Favel says.

"Tina would bring them home and just hang out with them," listening to music or playing games, Favel says. "She had such a big heart. She wanted everybody to feel safe. She wanted everybody to feel loved and accepted."

Perhaps the thing Favel misses most is her niece's laughter.

"It was contagious. And it was like a little machine gun," Favel says.

Awakening the Bear Clan

An alert goes off on James Favel's phone. A girl has been reported missing by her family — not to police but to the Bear Clan Patrol.

Favel flashes the screen of his phone.

"Missing girl," he says gruffly.

A former trucker and convicted felon, Favel (who is not related to Thelma Favel) leads the patrol through the streets with a confident swagger. The disparate group clad in bright yellow vests is in a garbage-strewn back lane, picking up dirty needles and putting them in sharps containers.

Favel's rough edges soften when he talks about the reason he's here almost every night.

"I started this because of what happened to Tina Fontaine. That was the switch that flipped, that was what snapped in my mind, myself, my family, my community. That's what Tina Fontaine did. That's what came from her suffering."

The Bear Clan was formed in 1992, but the group had been hibernating for years. Favel and others in the community say Fontaine's death "woke up" the Bear Clan.

Their current den is deep in the William Whyte neighbourhood, which is the city's poorest and most crime-plagued. It shares a meeting space with Ndinawe, an inner-city youth outreach shelter that briefly housed Tina near the end of her life. It recently renamed and dedicated its 24-hour drop-in centre to Tina.

From here they walk the streets, through back alleys and under bridges, handing out water, fruit and hope.

Favel knows they are making a difference.

In the very first year of the Bear Clan, he bumped into two women in their early 20s with a young girl in tow. Something wasn't right. As they walked away, Favel noticed another little girl off to the side, who had been with them.

She started crying.

"I was like, 'What's the matter?' And she said, ‘I don't want to go with them. They're going to do something bad. That girl is only 13.'"

He yelled out to the women to come back and had what he called "a bit of an altercation."

"It was the intention of the other older girl to take that 13-year-old child and sell her to a 23-year-old male friend of theirs, and that's where they were going at that time," Favel says.

"Because we were there and because we engage with people we come into contact with, and because we act, we stopped the exploitation of that minor child, and that's one of the things that galvanized it for me. We can have that kind of an impact just by being here, just by talking to people."

Mama Bears

Samantha Chief pulls the wisps of sweetgrass smoke toward her head, her heart and her feet. Every meeting of the Mama Bear Clan begins with this purifying smudge.

Run by mothers and grandmothers, the Mama Bear Clan offers a more nurturing alternative to the Bear Clan.

"I love it when I go out to do patrol because I can spread my love and joy and say, like, don't give up hope. You know, there's people out here that care still," Chief says.

Burly men walk alongside the women, who pull wagons full of first aid supplies, personal care and toiletry packages, sandwiches and water. They stop outside a hotel and bandage an older woman's arm, which is bleeding from a fall.

Chief is warm and open. She looks people who are used to being ignored in the eye. She hugs people most others would shun. And she does it because she, like Tina Fontaine, was here once.

"I don't even know if I was raped a few times, you know, but I woke up thinking something had happened to me, like, by the people who I thought were gonna protect me and keep me safe for the night to sleep," Chief says.

"It's scary out here on these streets…. I still cry about her and I think about her."

A few feet away, Alexia Légère hands out the last of her homemade sandwiches. She has harsh words for the authorities who were supposed to help Tina.

"They weren't out there looking how we look, like, when we have a missing person, we're on the street. We're looking in dumpsters, we're looking in back alleys, we're looking everywhere."

Légère's eyes flash in anger.

"The system just let her down in that aspect. There was no one there to protect her."

Now, on these nights when Bear Clans walk, there are people who have made it their purpose to protect those in need.

But Samantha Chief doesn't think that is Tina Fontaine's only legacy.

Samantha Chief walks with the Mama Bear Clan.

"She finally opened a lot of people's eyes, you know, to all the bad things that happen to us Aboriginal women," Chief says, her voice breaking.

"We're people too, you know. We're not just pieces of trash you can throw away. We have value to others. We're not — we're not who they portray us to be. We're not all street walkers, we're not trying to just do this because it's our choice, you know. We're people. We need to be honoured and loved just like regular people."

As the Mama Bear Clan returns to its home base, the grandmothers are outside in long green skirts, waiting for them. They begin drumming and singing in Ojibway. It's like a beacon.

People out for an evening walk, young families pushing strollers, kids who were playing and Mama Bear Clan members come together, feeling strength and unity in the drumbeats.

A young waif of a girl in track pants and a cropped tank top lingers on the outer edges. Her exposed belly is concave. She is carrying a stuffed backpack. Her thin arms are covered in what look like bruises from fingers digging into her skin.

She draws closer and closer to the singing. A smile of recognition and belonging spreads across her face and she starts singing along and swaying her slight frame. The song ends and she walks up to one of the women of Mama Bear Clan, who hugs and holds her as they talk.

It's easy to wonder whether a moment like this might have spared Tina Fontaine from her fate.

Still waiting for Tina

At home in Powerview, Favel is sitting on the sofa where she spent many afternoons with Tina watching their favourite shows: Law & Order and Criminal Minds.

"It's heartbreaking. I still long to ... hear her calling for me. I can still hear her sometimes," she says.

"I'Il say, 'Just come sit beside Mama, babe,' because I know her spirit is still here. I don't want to have her feel left out, so I always, I still invite her to come and sit beside me because this is where she sat with me all the time."

The curtains are drawn. They have to be, Favel says.

"If they're open, I'm always looking down the road to see if she's coming home. I can't keep my curtains open because I'm still waiting for her."

Tina, of course, is never coming home. Her body is laid to rest several kilometers down the road, next to her father, who was beaten to death in 2011.

His death made Tina long for a deeper connection with her mother in Winnipeg. She made a deal with Favel. If she ended the year with a solid report card, she could go visit her mother in in the city for one week.

"She just aced everything: math, science. Everything she aced, so I had to hold my end of the bargain up," Favel says.

Tina's mother, Valentina Duck, had long struggled with substance abuse, but Favel learned she had recently won visitation rights to see some of her other children. It seemed like a good time to let the teen get to know her mother better.

"It was just supposed to be one week," Favel says.

The visit did not go as planned.

Valentina Duck was not in a good place when her daughter arrived in Winnipeg. Within days, Tina was on the streets in what would ultimately be a death spiral.

Tina's last weeks on this earth have been well-documented in the news and the courts. She was homeless, exploited, underweight, using drugs and constantly slipping out from under the guardrails of the systems that were supposed to protect vulnerable children like her.

Timeline: From Tina Fontaine's arrival in Winnipeg to Raymond Cormier's arrest

Most critically, on what may have been one of her last days, she came into contact with police, the medical system and the child welfare system all within a 24-hour period, and all three failed to throw her the lifeline she needed.

Fontaine's death has been characterized not just as a crime but as an abject failure of the child welfare system.

'Do better'

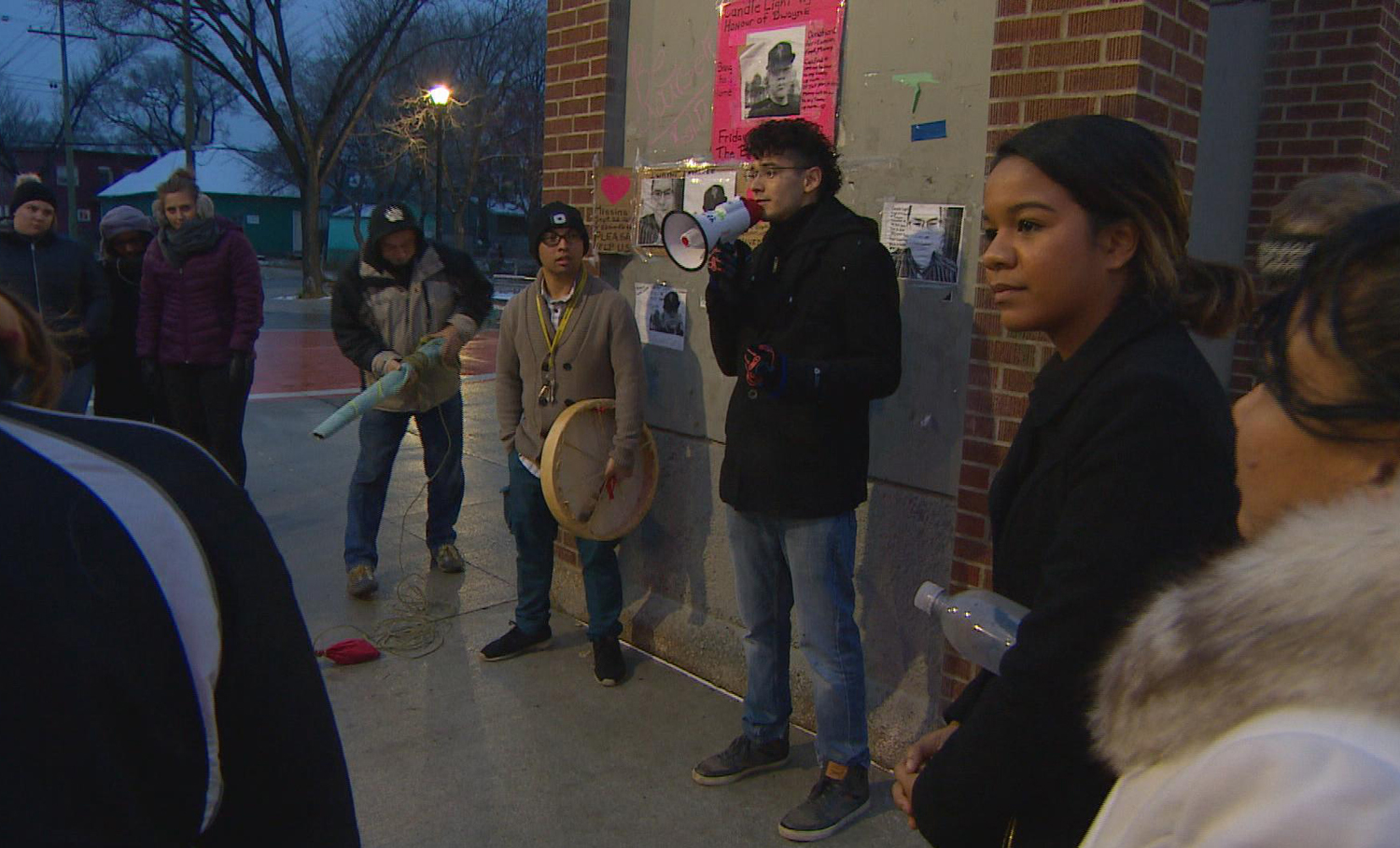

On the kind of cold Winnipeg night when most people want to stay indoors with a hot mug of something, some two dozen people are standing around a bell tower in the middle of the city's poorest neighbourhood.

They're listening to a thin, bespectacled young man with a curly mohawk and a megaphone. He urges them to think about what parts of the system aren't working and what they can do to fix it.

Michael Champagne can be found leading the discussion here every week since he started Meet Me at the Bell Tower eight years ago.

The topic of Tina Fontaine has come up more than once over the years.

"We all failed Tina Fontaine, myself included," Champagne says. "We all failed Tina Fontaine by allowing our systems to operate in the way that they have for so many years, unchecked. This is a failure of society."

Champagne and others from the community form Fearless R2W, a riff on the postal code of one of the more troubled neighbourhoods where they meet. The group's aim is to broker changes to the child welfare system and prevent tragic outcomes.

A brainstorming session on improving communication between front-line workers and families leaves very little white space on the whiteboard in their meeting space. While the positivity of some of the ideas is punctuated with happy faces, there is no escaping the grim realities that pushed this group into existence.

"The way that Tina was failed is the way that many kids in Manitoba are being failed right now by the child welfare system, by the police force, by our medical system. And I think that the way that any system is able to continue in this way is when those that are in positions to help look in the other direction and they say, 'Not my problem.' "

Champagne leans in a little, fire in his eyes.

"There is no such thing as other people's children. Those are your kids. Those are my kids and we have to do better by them."

Pride and anger

Many miles away, in a Powerview living room with the curtains drawn, Thelma Favel is proud.

"Tina's legacy to me is, like, to save other children from her fate, and I think she's doing that ever since this thing happened."

While there is pride, there is also anger.

"I don't know why it had to take this case. Why [it] had to take Tina to make everything go. Why? Why?" Favel asks. "When there was so many. Other women are still missing."

She pauses.

"She was a tiny little girl but she started a big movement," Favel says. "And that makes me proud.

"I still want her home, though. I am proud for what she's doing, but I would trade all that just to have her home."