March 29, 2018

In the 1770s, Moravian missionaries sailed into Inuit communities on the coast of Labrador with freshly written musical scores by Handel, Bach and other composers.

At the time, they couldn’t have known what an enduring role that music would play in the lives of generations of Inuit.

I learned a great deal making Thumbprints in Seal Oil, a radio documentary about a 250-year-old choral tradition — a traditon that started as a paternalistic relationship but was transformed into a tool for change by the Inuit.

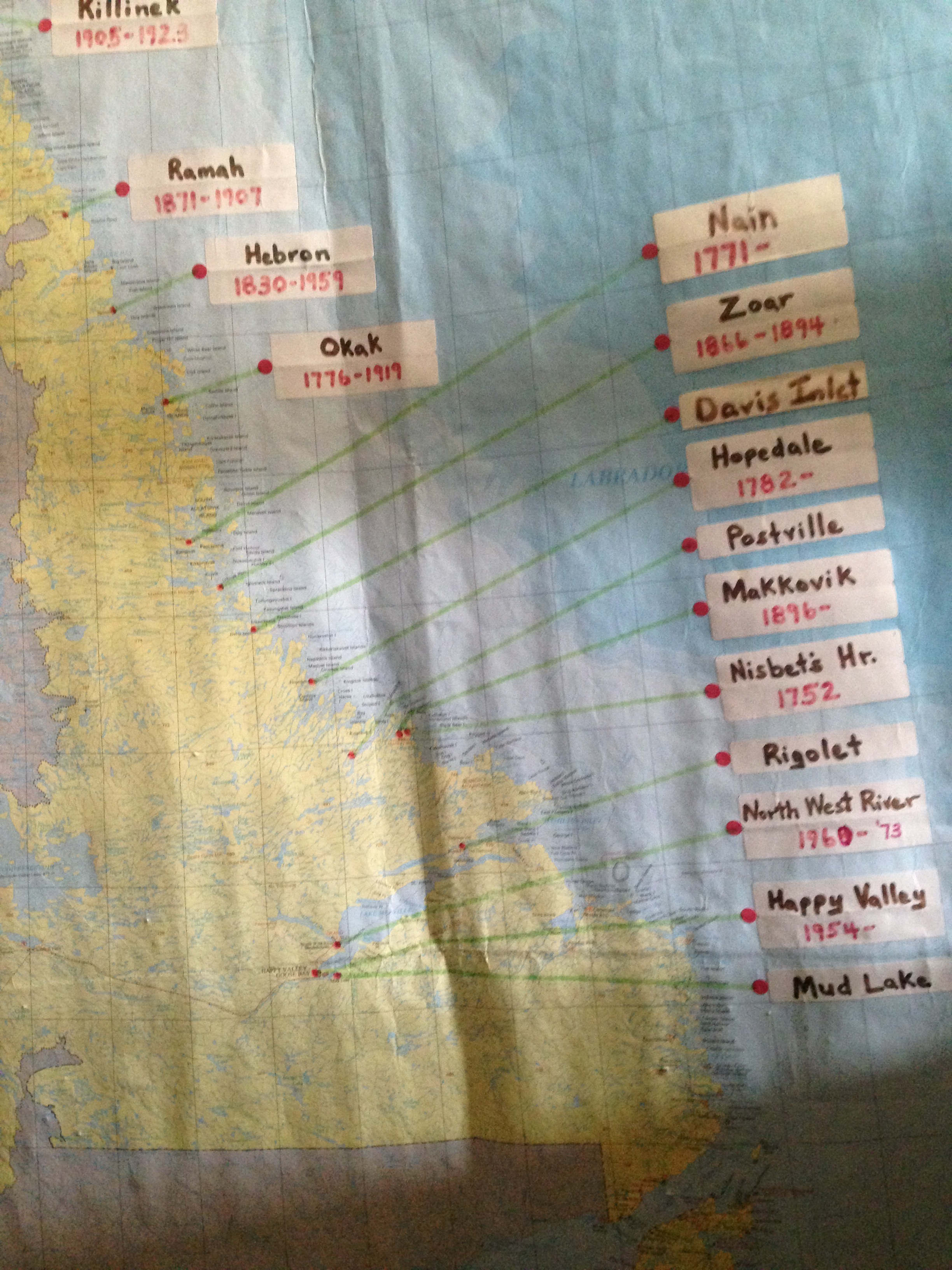

Musicologists now believe hymns by Handel, Bach and others made their North American debuts in the small wooden churches of Makkovik, Okak, Nain and Hopedale. As well, some hymns credited to Germans were in fact written by Inuit composers. In addition to those historic firsts, the music played a role in contemporary Inuit identity and self-government in Nunatsiavut.

As well as producing documentaries for CBC, I am a member of Lady Cove Choir. As we were preparing for a concert called Makkipok celebrating this unique tradition, I travelled to Hopedale.

I went there with choir director Kellie Walsh, who leads Shallaway and Lady Cove choirs, to find out more about the tradition and to meet the new generation of Labrador Inuit choristers.

But first, Kellie and I, along with six teenage singers from Shallaway Youth Choir, hop up the coast of Labrador in a twin prop from Goose Bay. It’s -24 C, but the sun is shining and the coast of Labrador is spectacular from the windows of our small plane.

As we descend into Hopedale, the Shallaway singers break into song.

Kellie Walsh and her six Shallaway choristers: Amanda Davis, Claire Osmond, Elizabeth Johnson, Sarah Dunphy, Claire Donnan and Alice MacGregor sing for the co-pilots.

Teachers and students of Hopedale’s Amos Comenius School were waiting with snowmobiles and komatiks to ferry us across the frozen bay into Hopedale, the capital of Nunatsiavut.

The six Shallaway singers will join choristers from all over the coast at a choir camp this week called the Pan Labrador Choir.

Kellie Walsh, who has been coming to Labrador for more than a decade to work with young singers, recently formed a choir of Inuit youth called Ullugiagatsuk.

“We talked to Kathleen Allen, the composer, and she wrote a piece, a very special piece for those kids to bring to Ottawa for the 150th anniversary,” she said. “I called up the organizer of this big choral project and said we’re going to be singing in English and French on this concert, we should be singing in Inuktitut as well. And Lydia Adams said yes, is it possible? And this choir formed and it was so incredible.”

There are singers here from the communities of Makkovik, Rigolet, Nain and Postville.

They’ve all come to this village of 600 to sing and share their Inuit culture.

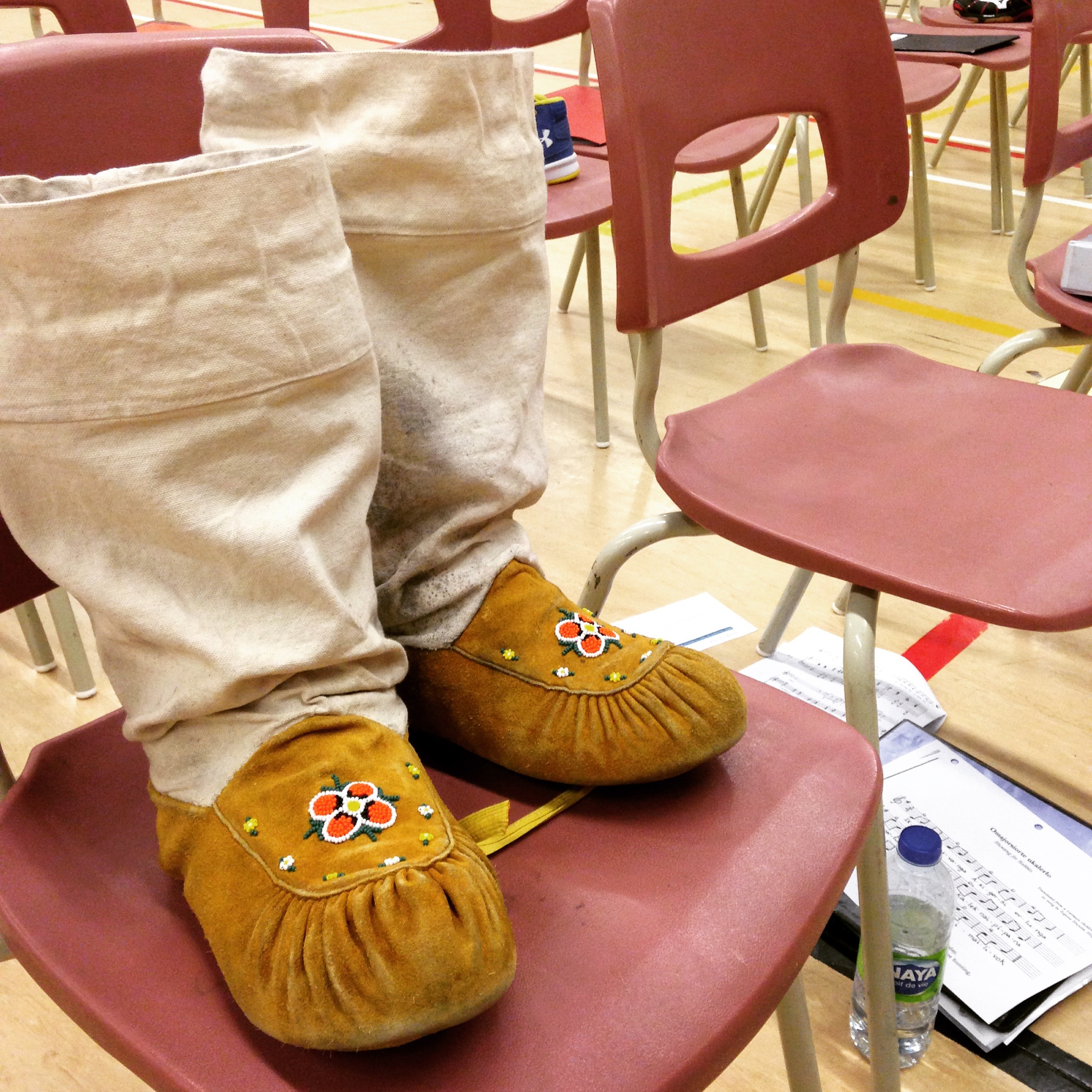

During the week, there are day-long rehearsals punctuated with community sealskin crafts,

snowmobile tours to see the successful result of a polar bear hunt, lunches of arctic char and fired bread “panitsiak” and an evening of Inuit games.

Listen to Angela Antle's two-part documentary on this story, produced for CBC Radio's Atlantic Voice:

Two hundred and fifty years ago, when German Moravian missionaries arrived on the coast, they built churches, schools and trading posts. The Moravian mission buildings have stood in Hopedale since the 1780s.

David Igloliorte is an archivist at this national historic site. I asked him how the Moravians from Germany were accepted by the Inuit.

“Before coming to Labrador, the missionaries were in Greenland and the Greenland Inuit told the missionaries that they had brothers and sisters living across the water, referring to Labrador. And when they came, they knew how to speak Inuktitut and dressed up like the Inuit. That was in the 1770s.”

The Moravian museum is filled with all kinds of items from candy tins to a sealskin kayak and a giant blacksmith’s bellow. David Igloliorte stops in from of a display of battered brass instruments.

“Here next to the piano and on top of that is a horn, there is a date on it. It’s a 1750s horn,” he said. “This one was made in Europe, we see horns and tubas , the European instruments they have their keys on a horizontal level, but the North American keys are little pumps.”

“My father, he played in the church choir. He would come home with his musical instruments he had three of four of them at home actually, a trumpet, violin or fiddle and a little organ and he would be practising church music and what’s interesting and from what I’ve read and what I am transcribing and even some of the local people would come up with their own musical tunes for the church.”

Musicologist Dr. Tom Gordon has been researching and digitizing the Moravian scores in Labrador for more than a decade. He confirms that some of the music attributed to German musicians was actually composed by Inuit.

“Ernik Erligidlarpagit is in very simple four-part style and I’m 99 per cent sure it was written by an Inuk composer — an organist. It’s incredibly beloved by the people of the coast,” Gordon said.

“People talk about getting ready to sing it.They look forward to this as they do the Hosiana. In its 11 verses, it tells the story of Passion Week, day by day, and it does so in a dialogue between Mary who asks her son, why are you putting yourself through this? He responds in each verse and assures her he knows what she is doing and this is for the good of all mankind.

“It’s striking for a lot of reasons.The story is so non-hierarchical church language. It’s told as if it were a story instead of dogma.”

Hopedale choir director and organist Nicole Shuglo is keeping the tradition alive by teaching the Moravian hymns to a small choir of young singers.

“So often we talk about the past and lament that things are changing. And it’s so encouraging to hear these beautiful young singers and not just thinking this is what it was, but celebrating what it is today and moving it on to the next generation.”

When I get back to the school, Kellie Walsh is working with a group of Inuit drummers for the concert’s finale.They will drum along with the choir singing Oscar Peterson’s Hymn to Freedom.

Although the Moravians were generous with their own music, they banned traditional Inuit drumming.

Teacher Natalie Jacque leads a group of young Inuit women who drum with Ullugiagatsuk.

“It was traditionally the men who were the drummers long ago and it was banned around the time of the Moravians and the language was lost and the culture,” she said.

“Ten to 15 years ago, it was incorporated back and the language is really making a come back and same with throat singing. I didn’t understand why it was banned, as a child, but you didn’t really want to feel different than anyone else. Now you feel that you’re part of something when you drum or throat sing or when you’re speaking your language.”

Kellie Walsh says it’s important to bring young people from Shallaway choir to Labrador to be exposed to Inuit culture because kids who sing together understand each other. She chose Hymn to Freedom as the finale at the Hopedale community concert because it represents those ideals.

“It’s really incredible as a choral conductor to be able to take a piece of music and be able to talk to young people about you know there is a possibility for us to come together and be respectful and live in a peaceful world in a way that emulates the lyrics of this song. Hymn to Freedom can be powerful to a ninety year old and a five year old. When every heart joins every heart when every hand joins every hand for me it really speaks to what choral music is.”

A week later, we’re back in St. John’s. Kellie Walsh is leading a 90 voice choir made up of members of Lady Cove and Newman Sound. We’re rehearsing a full programme of Moravian hymns in Inuktitut for the Makkipok concert.

Since joining Lady Cove Choir, I’ve learned and performed music in Latin, Finnish, Xhosa and Bulgarian, to name a few languages. But many of us are finding the Inuktitut text difficult. One detail Dr. Tom Gordon told me about the scores has kept me grounded.

“These sheets are sort of museum worthy now but they were used every week by people for whom the rest of their week was very rough,” he said.

“So in the corner of the sheets you see the stains of seal oil that was embedded in the fingers of the singers. The music showed very much their use.”

Those thumbprints are such a strong symbol of the indelible impression the Inuit have had on this German music.

But as well as having difficulty with text, I shared with Kellie Walsh that I was feeling conflicted about celebrating music that was a tool of colonization. She admitted to feeling unease until she performed the music on the coast.

“I can only speak from my own perspective and I understand what you mean,” she said, describing her first visit to Nain, and singing in Nain’s church.

“Having an elder come to me and saying I feel like our ancestors are here tonight. That washed away every bit of worry of questioning and only filled me with this is so special and I am so lucky to be doing this and to be sharing this with people.”

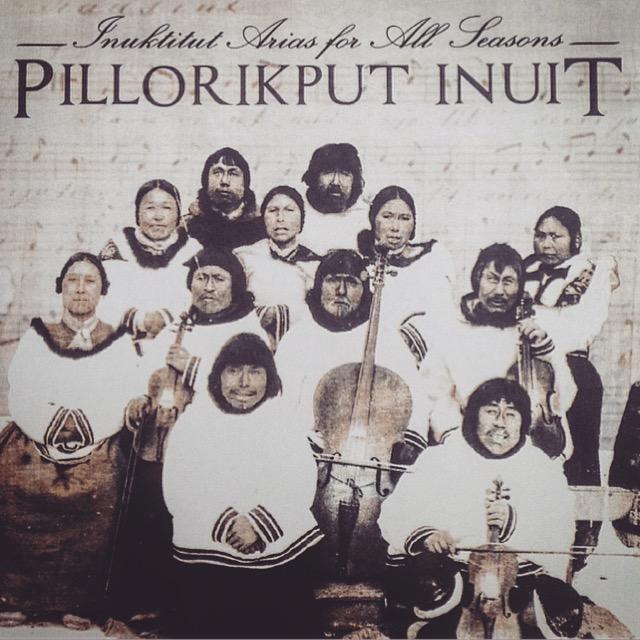

Soprano Deantha Edmunds is performing with us. She has sung many of these songs before on a CD called Inuit Arias for All Seasons: Pillorikput Inuit. Deantha’s father grew up in Hopedale and would’ve heard these songs in the same church where Deantha sang at the CD launch.

“To stand in that beautiful Moravian church in Hopedale singing the classical music that I had sung all my life in Inuktitut and to stand in the church where my father was raised it was indescribable,” she said. “I felt like I was coming home.”

She said her father could pick up any instrument and play it. “He had a beautiful singing voice, could play guitar, he was in a rock band in university and was a wonderful music lover and appreciator of all kinds of music,” she said, adding that her father at Christmas would sing O Christmas Tree in German, Inuktitut and English.

“He would tell my siblings and I about the beautiful choir music and the brass bands and to know that the Moravian missionaries and the Labrador Inuit were making music using brass, strings and four part choral scores before most of Canada, before there were orchestras in most of Canada.”

Musicologists like Tom Gordon believe there were pieces by Handel, Bach and others that made their North American debuts in the small wooden churches of Makkovik, Nain and Hopedale. But more than those historic firsts, Kellie Walsh recognizes this music as nothing short of transformative.

“I have felt so lucky to have had the opportunity to learn this music, to be in Labrador to sing this music with the people of Labrador, to learn Inuktitut from Karrie Obed, to conduct people singing this music, to actually be in Hopedale on Easter Sunday and sing in that church,” she said.

“[This] has been one of the most special things I have done as a musician as a human being, those relationships, those experiences.”

Mary Sillett, the clerk and registrar for the Nunatsiavut government, is a former mayor and former head of several national Inuit organizations. She is also a member of the Moravian Church. Her pride in the music is tempered by a recognition of the missionaries’ negative impact on every aspect of Inuit life.

“I remember reading some of the diaries of the missionaries and they wanted the Inuit to come and work for them from nine to five. And they had such difficulty with that. But, as Inuit, we’d have to hunt fish and trap and those were priorities,” she said.

“The other thing that I read about, in traditional Inuit society, the Inuit men had many wives and the Moravians didn’t like that. They were scandalized by that — they wanted monogamy. That was one of the most difficult things for them to change, to change how people used to live. And I know many cases, even my own family, my grandfather had two wives. And some of the people had accepted the Moravian way of thinking and there was conflict.”

Mary Sillett does attribute her early educational opportunities to the Moravian church.

“All of the opportunities I had [were] because of the Moravian church.They took a special interest in people who achieved academic excellence and they were incredible record-keepers. They ran the schools and were responsible for the preservation of Inuktitut in many ways.”

On the night of the Makkipok concert, the Basilica of St. John the Baptist — a magnificent Roman Catholic church in St. John’s — is filling up with people. The altar is lit in the green and blue of the Labrador flag and many people in the audience are wearing Labrador parkas called sillipaks. The audience is welcomed by the president of Nunatsiavut, Johannes Lampe.

“Long before there was a Canada and long before there was a Newfoundland, Inuit with the help of Moravian missionaries adopted a culture,” he said.

“Inuit have values which are really positive where sharing is the most important value that Labrador Inuit have and we use it for other things too. Either by singing and by sharing food and most certainly and building a relationship as families and communities you know, no matter who it is. It is quite valuable to be an Inuk and I believe that Inuit have always done things in good ways. Deantha Edmunds is a role model and I hope young Inuit will pick up on this and be inspired to do what Deantha, Tom Gordon and Kellie Walsh are doing.

[You can watch the whole concert here. Scroll to the 30:53 mark.]

Deantha Edmunds says the fact that this music has thrived is an example of the resilience of the Inuit of Labrador. Resilience and celebration and pride in our own.

“When I sing it sometimes I wonder about the singers themselves, who sang this? Whose solo was this in the church? What instruments did they have? How did they make it their own? What was the one of voice? Was it a child? An elder?” Edmunds said.

“Then to feel my feet on the ground and breathe deep and feel myself — it’s part of the story of the Labrador Inuit from hundreds of years ago. People say oh my goodness you’re Inuit and you’re from Newfoundland and you sing classical music? Some people think that that’s odd. I don’t. I think it makes absolutely perfect sense that I am a classical singer because I am Inuk, because I have roots in Labrador. Because of that music history. The gift of the music that the Moravians brought to Labrador and the Inuit made their own.”