February 25, 2021

Nearly every day of the pandemic, Brad Bridgen has been dodging hugs and explaining why fans aren't allowed at hockey games.

In his line of work, these small tasks have come to define his days.

Bridgen is a direct support worker for Community Living Windsor. He supports and cares for four men who are between the ages of 50 and 70 years old and have a range of physical and mental disabilities.

As an essential worker helping an at-risk group, Bridgen is one of thousands in Windsor-Essex who can't work from home.

When crises happen, emergency service personnel and health-care workers are typically the ones who carrying the burden. But the pandemic has redefined the frontline worker so that it now includes those who stock grocery shelves or teach kids.

As of December 2020, roughly 103,600 people across Windsor-Essex were employed in sectors that would require them to physically go in to work, according to Statistics Canada data.

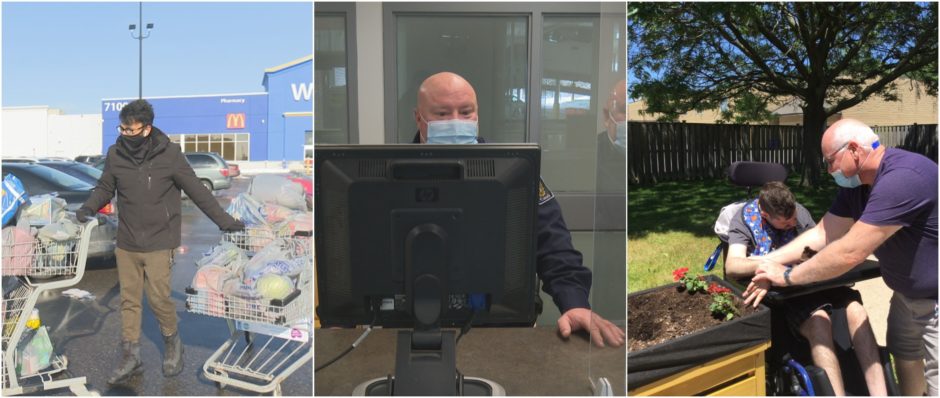

CBC News spoke with three of these people, including Bridgen, about their day-to-day work in the middle of a strict lockdown order. From an Ambassador Bridge border officer to an Insta-cart shopper, these are the people who continue to keep the region going despite all the ways it's had to stop.

Though their jobs are very different, each of them were grateful that their work allowed them to get out of the house and be helpful to others.

Living the pandemic twice

From Sunday to Thursday, Bridgen arrives at his workplace in south Windsor at 7 a.m.

Bridgen is not only leaving his home, he's entering someone else's — something many haven't done since March of last year.

Before entering the home, he washes and puts on gloves, a mask and a face shield.

Every morning for the past 15 years, Bridgen says he's greeted at the door with a hug from one of the residents. But for the last 11 months, he's had to keep his distance.

"He wants to come over and try to get a hug and we have to say 'no, no, no,'" Bridgen said.

"That's very, very difficult and you can see when someone you've known all these years is hurting and you want to comfort them whatever way you can, but you can't. Sometimes words just don't cut it."

Like everyone else, the men in the home have had to adjust to a different routine. This means that long drives, outings to hockey games, grocery shopping and family visits have all had to stop, Bridgen said.

"Things that they used to like to do they no longer can do, and then it's trying to answer the questions," he said. One of the men, who used to enjoy going to watch hockey games, asks why he no longer can.

After nearly a year of giving the same response, Bridgen says he can tell his answers are "wearing thin."

"Sometimes words just don't cut it."

- Brad Bridgen

"I think that's the biggest challenge: knowing someone really desires to do something and we're not able to facilitate it," he said, adding that he knows it's to keep them safe.

Despite how cautious he's being, at the back of his mind lingers the fear that he'll bring COVID-19 into the home.

To protect the residents and keep peace of mind, Bridgen says he's severely restricted his own way of living.

Though necessary, he said it's taxing on his mental health as he's recently become a widow.

"It's difficult to come home at the end of the day and be by myself after having been with people and to not have someone that I can download to," he said.

And it also means his life has become pretty routine.

"The days have become so much the same, maybe that's what sticks out the most, everything's the same. It's like groundhog day all over," he said.

And while every day may feel like a carbon copy of the one before for most people these days, for Bridgen it's because he's essentially living the pandemic twice.

Nearly everything he does for himself, he repeats for the four men he supports — from ordering and sanitizing groceries to important bank visits.

"It's got to be done so you do it, " he said.

Essential deliveries

And while Bridgen's work forces him to limit the places he goes to, Insta-cart shopper Syed Zubair is going out more than ever before.

When Zubair first started buying groceries for people at the start of 2020, it was a way to pass the time and pay off his University of Windsor master's tuition.

But in just a few months he went from Insta-cart shopper to essential worker. Each week, he said he shops and delivers items to about 250 to 400 people.

"It feels good," he said. "I get immense joy when I'm helping some people, especially when they are happy and grateful I'm providing the service for them."

Typically his day starts around 6:50 a.m. as that's when the first batch of orders come in for Walmart. By 9 a.m. he's also received orders for the Canadian Superstore, Zehrs and Costco. Then it's time to shop and deliver.

On any given day, Zubair is walking 11 to 12 kilometres worth of grocery store aisles.

"I know each and every store in my head now, I know all the particular items by heart. And trust me I didn't know there are so many particular names for the produce," he said.

But he isn't only picking up groceries.

"I have shopped each and everything in a particular store, from picking up blankets to pillows, being a Santa for the kids, picking up toys, you name it," he said. One order he had asked for four iPads, two iPhones and three MacBook Airs.

While the shopping can be fun, the best part of the job is the drop-off — when he sees how grateful people are, many of whom leave him handwritten notes and large tips.

"When I delivered these items, there were certain people who were almost in tears," he said. "I love the senior citizens ... I'm a person who loves to speak to them and spend time."

"It takes care of my health as well as it takes care of my finances and it keeps my emotions in check as well because helping others can actually make you feel happier."

Guarding a busy border city

For the majority of John McDonald's 20-year career as a border services officer, he's welcomed travellers into Canada at the Ambassador Bridge.

But this is the first time where he's seen so few people cross for months on end.

Through lockdowns and stay-at-home orders, McDonald has continued to commute from his home in Belle River to the Windsor-Detroit border.

As someone who manages the movement of people between two neighbouring countries, McDonald says what's stood out to him during the time of COVID-19 is the distance that now lies between them — from the plexiglass, mask and shields that separate him from travellers to the geographical distance that is keeping people apart.

"You can see now that it's not so easy to cross the border to see family and ... that's a heartache for sure."

- John McDonald

"I have relatives who live in Michigan and I haven't seen them for close to a year now ... and the travellers that attempt to come through you can see now that it's not so easy to cross the border to see family and ... that's a heartache for sure," he said.

Another part of the job that's different is the series of questions officers are asking travellers, with quarantine plans and health symptoms the latest additions.

Often the most difficult part about this is hearing the other person through all the layers of protection, McDonald said.

"You have to speak up a lot ... and it's a common tendency instantly for a traveller to pull their mask down to talk to you so a lot of time it's 'oh no keep your mask on, just speak up for me please," he said.

Despite the challenges and risks that COVID-19 has brought to the job, Bridgen says he's glad to have a reason to get out.

"As time's gone on I'm thankful that I get to go to work," he said. "It's good to get out of the house."