March 6, 2020

This story is part of Stopping Domestic Violence, a CBC News series looking at the crisis of intimate partner violence in Canada and what can be done to end it.

Across Canada in 2018, more than 75 people lost a parent to intimate-partner violence.

While there were no intimate-partner homicides in Newfoundland and Labrador that year, there is a long list of people orphaned by violence against women in the province in the past.

The details of this story are disturbing and may not be suitable for everyone.

I. Daniel and Judy

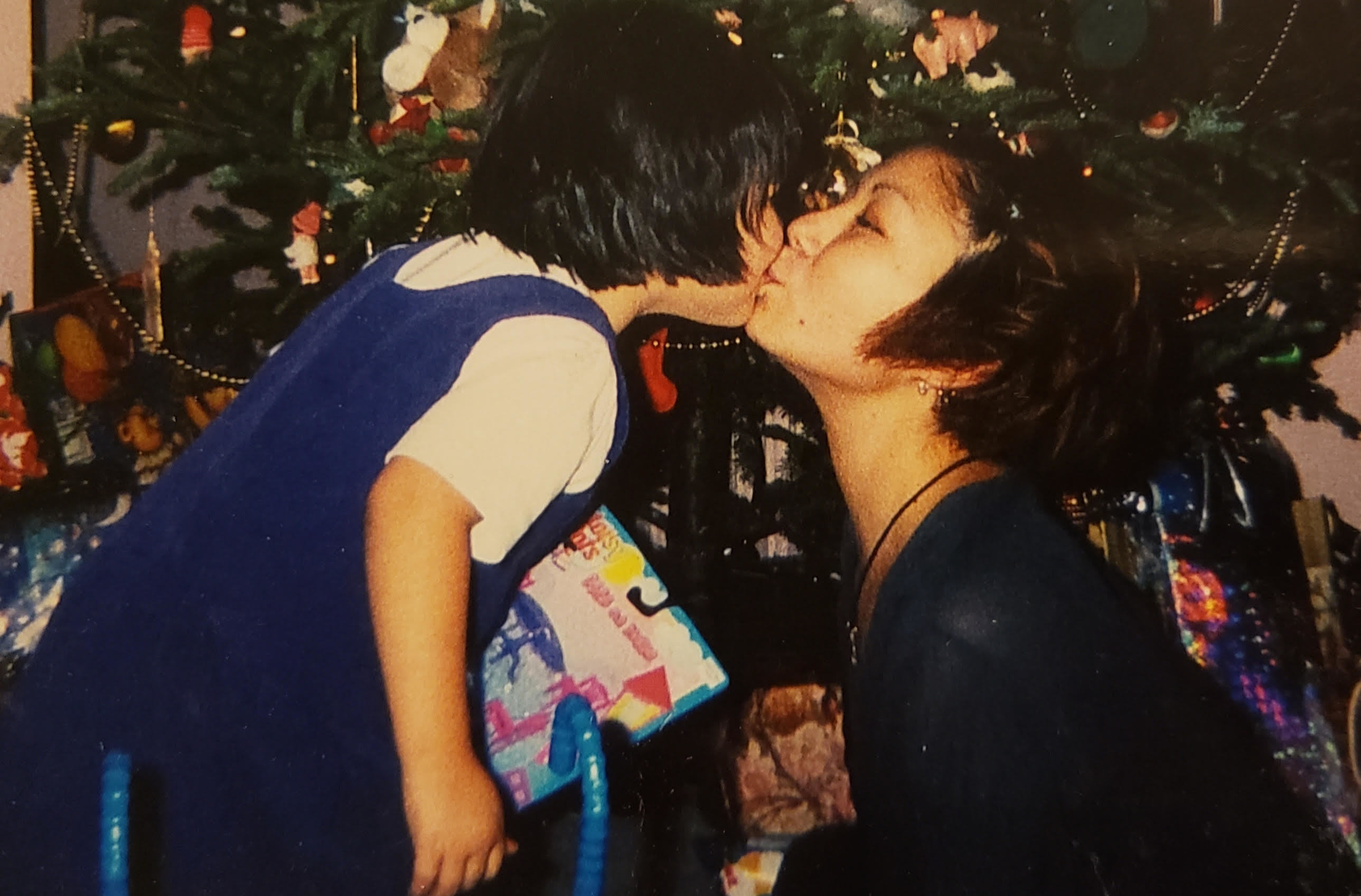

With a wide smile across her face, a doting mom cradles her firstborn baby on a carpeted floor.

It was 1994. Daniel Benoit hadn't yet reached his first birthday and his mother Judy Ogden was still alive.

"I was pretty chubby," Daniel laughs as he watches the grainy video from his home in Stephenville, N.L.

The video was recorded by the Pathfinder Learning Centre where Ogden was a student, upgrading her high school to better position herself and her children for a future cut short.

At 26 years old, Daniel has already outlived his mom.

"She was good with the community. She was good with everybody that she worked with," Daniel said.

"Everybody knew her as a loving and caring mother."

Then there are the memories he would rather forget. The traumatizing images that may never leave him.

Even at a young age, Daniel feared his father Dale Ogden, a menacing figure who abused Judy Ogden and her two children, before she cut off the relationship for good.

The couple was heading for divorce in 1997, but he disregarded the court order telling him to stay away.

Ogden would drive up and down their street in Port au Port West at all hours of the day and night. Judy Ogden nailed the windows shut and stuck a knife in the door to impede anyone trying to get in.

She did everything she could to stay safe.

A warm July night in 1997, four-year-old Daniel was asleep in his bedroom when his father came in his house, then his bedroom.

"He came into my room and he woke me up ... He said there was a dog in the house that was trying to hurt mom. He said, 'You're going to hear some screams and some noises but I'm going to kill the dog,'" Daniel said.

"He basically took my hand and walked me into the hallway, where he proceeded into my mother's room. He basically just went at her with brute force."

Ogden used his fists to shatter the bones in 25-year-old Judy's face. He used the back of an axe on her body.

"I watched my mom literally take her last breath, so to say, in a way I never should have," Daniel recalled.

His father then went to the washroom to clean up, Daniel said, before grabbing Daniel's infant sister from her crib and taking the two children back to his home in nearby Kippens.

The next day, Ogden brought the kids back home, and played the part of worried husband — repeatedly calling the home phone looking for Judy.

Of course, no one would answer.

Daniel remembers his father borrowing a ladder from a neighbour and guiding his young son up to his mother's bedroom window.

"Not only did I have to relive it the night before, I had to look at it in broad daylight," Daniel said.

"The last image I have is my mother's body lying on the floor next to her bed. It's an image I may never shake from my head."

Daniel's father was arrested the same day, and the boy's own evidence would be a key piece to the RCMP's puzzle — a child's drawing of a man holding an axe and a woman lying on the floor.

Dale Ogden was sentenced in 2000 to life in prison for second-degree murder. The judge set his parole eligibility at 14 years.

"I think you have a different outcome in life when this happens to you. You experience so much at a young age that you gain knowledge that most people don't get throughout their lifetime," Daniel said.

It wasn't until Grade 10 that Daniel could look at a photo of his mom without throwing up.

Today, he wishes he could see more. Especially for his own son, Dominic, who is four.

"Everything that happened to her, the red flags that I've seen, I can educate my son at an early age how to treat women the right way."

Daniel plans to face his mother's killer at the next court or parole hearing.

Ogden was released from federal prison in 2016 and began meeting women using dating websites. His parole was revoked.

The Parole Board of Canada's written decision to revoke Ogden's parole shows that he dated several women and lied to his parole officer about it after he was released from prison in August 2016. He remains in federal prison.

Daniel's greatest fear is that Ogden will hurt — or kill — another woman.

He believes it's time to show Ogden that he's grown into a good person and father in spite of him.

"He got the better of her ... but he'll never get the better of me."

II. Lauralee and Brenda

On a normal day, Lauralee Gillingham turns her head away from her former family home when she drives down Torbay Road, a main thoroughfare in St. John's.

But today is different. She is revisiting the scene of her mother's murder.

"I don't come here. I try to avoid it at all costs coming here," Lauralee said.

The apartment building is the last place she shared happy memories with her mom, Brenda Gillingham, curling up on the couch and watching TV.

It's also where her mother's ex-boyfriend took Brenda Gillingham's life.

"I wrote a letter actually and put it on her bedroom door saying I don't want him staying here," Lauralee said of her mom's relationship with Cecil Pendergast.

"I met him a couple of times after that and I didn't like him."

For years, Lauralee watched as her mother chewed her nails down to the nub and stopped eating. Her mom was becoming a shell of the person she was.

Lauralee and her cousin sat Brenda Gillingham, 39, down weeks before she made the decision to leave Pendergast.

They wanted her to get out.

"We told her how beautiful she was, how smart she was. It's almost like she's never heard that before, it seemed," she said.

Lauralee stayed out the evening of her mom's murder. She wanted to wait until Pendergast came to collect his things and get out of their lives for good.

"[My mom] said, 'It'll all be over tonight' ... it'll all be over tonight," Lauralee said during an interview in St. John's.

Pendergast had control over the five-year relationship, according to Lauralee, and needed to know where Brenda Gillingham was at all times.

"He had her completely brainwashed. She wasn't allowed to see any of her family. She wasn't allowed to be attentive to me," she said.

Then Brenda Gillingham took control and ended the relationship.

Under the guise of getting his barbecue back, Pendergast entered through the emergency exit door of the apartment building on the evening of June 27, 2000. A child who recognized him as Brenda's boyfriend let him in.

"He went down the hall to the second apartment and drove himself in the door, taking off our welcome sign as he did," Lauralee said, "screaming: 'I'm going to

f--king kill you.'"

Pendergast had drank more than two dozen beer, and brought a 12-gauge shotgun.

Lauralee's 14-year-old brother was home at the time.

"He heard a bang. He said, 'That's just the barbecue.' He heard another bang. 'OK, that's just the barbecue.' Then he said he heard a big bang and he said, 'That's not the barbecue,'" Lauralee recalled.

"He ran up over the stairs and the first thing he saw was he thought mom played a joke and threw spaghetti on the wall. It wasn't. It was her face, it was her head. It was her brain."

Lauralee said she believes sharing the gruesome details of what happened to her mother is necessary to illustrate the seriousness of domestic violence.

Pendergast was originally charged with first-degree murder, but later pleaded guilty to second-degree murder. His parole eligibility was set at 15 years.

"I hope he rots because he deserves it. He's a bastard and finally we can rest. We're going straight to the graveyard and telling mom it's all over," 19-year-old Lauralee told reporters on the steps of Supreme Court in 2002. She stood strong, clutching her own child.

But it wasn't over for her the way she had hoped.

"That's not what happened at all. There were constant appeals. There were court dates," Lauralee said.

She attended parole hearings and got updates when Pendergast was given escorted temporary absences, then day parole, then statutory release.

"Cecil Pendergast is out now. He's happy. He has a girlfriend. He has a new life."

The Parole Board of Canada has imposed a special condition, which would require Pendergast to report any new romantic relationships to his parole officer.

Lauralee wants stricter sentences to deter others from committing the same crimes.

"Every unjust sentence bullies the victim. They don't think about us. My mom doesn't get to be escorted around. She doesn't get to go on day parole. She doesn't get to come back after 15 years ... but he does."

What happened to Lauralee changed her as a person and coloured the way she raised her own child, a son.

"He filled my heart, the hole in my heart. It's still there, but having him was the best thing that ever happened to me. It saved my life," she said.

Lauralee taught her son how to treat women. She never believed she, too, would be mistreated.

"I really thought I would know ... I ended up in a relationship a few years ago actually that I was being abused verbally."

Unlike her mom, Lauralee made a plan, got an apartment and an emergency protection order, and made a clean break.

Today, she's an advocate.

"Domestic violence relationships can and will end in homicide. That's the ultimate ending. The ultimate control. If I can't have her, nobody can. The detail needs to come out. Murder is not pretty."

III. Amena and Mary

It’s easy to do a double take when you see Amena Evans Harlick.

Her eyes and smile mirror that of her late mother Mary Evans Harlick, who was murdered when Amena was just six years old.

The comparison is the greatest compliment the now 23-year-old woman can get.

“It’s like the best thing to look like my mom because I think she’s the most beautiful woman in the entire planet,” she said.

“To look like her is a blessing.”

Mary Evans Harlick, an Inuk from North West River, Labrador, was adopted by a family in St. John's when she was an infant.

Amena's memories of her mother are innocent and childlike — nothing like the harsh truth of how Mary's life ended.

She remembers walking downtown with her mom, a talented Indigenous artist, and buying caramel squares at the corner store.

Amena remembers making paper airplanes and jumping on her bed. She remembers making Rice Krispie squares.

“She was the best mom she could be. She was a young mom and that can be difficult for anyone, but she made the best of it, and she made sure that the time she had with myself and my brother was incredible and memorable," Amena said.

After a day of drinking, Scott Gauthier — a man close to Mary Evans Harlick — strangled her using her own rawhide necklace, in his apartment in St. John's.

Amena's father shielded her and her younger brother from the evening news when gruesome details came to light each day of the trial.

Gauthier was convicted of second-degree murder in July 2006, and was sentenced to life in prison without chance of parole for 17 years. He remains in federal prison today.

“She was the most carefree person that anyone could have ever known. She knew how to bring a smile to anyone’s face and she loved everyone and her family so much. She was the best artist I could ever think of," Amena said.

Amena took a big step to keep her mother's memory alive when she testified at the National Inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls in March 2018.

"If you don't talk about these things, nothing will ever happen. Nothing will ever be solved," she said.

"We’re losing so many women and mothers and daughters, and people in general. Something needs to be done. If no one stands up for them, who is?”

Losing her mother to violence has shaken her level of trust and puts her mind at unease in day-to-day situations.

“I constantly think: I’m going to be another statistic. And I don’t want that to happen. It’s scary."

She feels pangs of jealousy as she sees girls and their mothers — a stinging reminder of what she has lost.

Amena wants to organize an event in the coming years to educate the public on violence against women, especially involving Indigenous women and girls.

She vows to keep talking.

And for people to never forget the name Mary Evans Harlick.

If you need help and are in immediate danger, call 911. To find assistance in your area click here.