The basement door to Milla Pub is shut tight, with a dowling nailed beneath the handle should the locked deadbolt look too inviting.

Closed now for several years, the pub on 101st Street near 106th Avenue was notorious, the epicentre of one of the city’s most troubled neighbourhoods.

But the basement of the Milla Pub building has a special place in local history. It was once Club 70, Edmonton’s first official gay bar.

The look of the building contradicts the common understanding of what gay bars look like today: colourful places in vibrant areas.

But that’s a recent phenomenon, said playwright and theatre performer Darrin Hagen, who calls himself Edmonton’s unofficial gay historian. Before society’s acceptance of the gay experience, LGBTQ people and their spaces were relegated to cities’ dead zones, Hagen said.

“That’s where the queers move in, because nobody else wants the space,” he said.

Gay bars flourished in Edmonton in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s. But as society’s acceptance of gender and sexual minorities has grown, the need for gay bars has lessened.

There are certainly fewer clubs today, but they still play an important role, said Rob Browatzke, owner of Evolution Wonderlounge, currently the only official gay bar in the city.

“As a person involved in organized queer life, thinking about a time when society would be completely accepting and affirming of everybody, I don't think we realized then that part of that might be the loss of those queer spaces,” Browatzke said in an interview.

Flash back to 1969

It has now been more than 50 years since Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal government decriminalized homosexuality. In Edmonton, the landmark legislation brought to the surface what was already going on underground.

“A bunch of enterprising queers in Edmonton decided since it’s no longer illegal, we should create a space where we can gather,” Hagen said.

That fall, Club 70 was born in the basement of what was then a Greek restaurant. It was meant to be named after the year the legislation passed, or at least, the approximate date.

“Even though it was 1969 they thought calling it Club 69 was a little cheeky,” Hagen said. “Plus, they were forward-thinking.”

The location didn’t last. The club was forced out after only a few weekends. “The landlord of the building found out what was in his basement and shut it down,” Hagen said. The owner locked the doors; Club 70 owners had to sue to get their sound system back.

They eventually settled into a building on 106th Street that would house LGBTQ spaces for the next 40 years — including the Cha Cha Palace, Boots and Saddles, and later Junction, a lesbian-run bar.

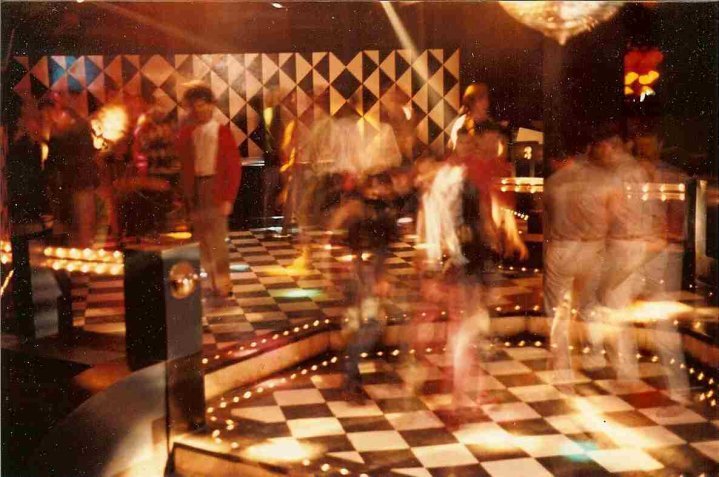

The now-burgeoning 104th Street used to be one of the city’s dead zones. It boasted two of the city’s most popular bars: Flashback, a Studio 54-style nightclub, and the Roost.

Gathering places

Gay bars are often loud and flashy, packed with people. As a founding member of the Guys in Disguise drag group, Hagen has spent years headlining stages in bars with exactly that vibe.

“The man that I am now is because of the woman I dressed as in the '80s,” he said.

But glitz and glamour aren’t the only attractions at gay bars. Until only recently, they were the only public places LGBTQ people could feel like themselves.

“The bars were sort of the town halls, the town squares, for all of us to meet,” Hagen said.

They provided safe spaces for their patrons. “Back then, being a drag queen was something that was kind of scary,” he said. “And you didn’t do it in public unless you were kind of brave.”

Bars insulated patrons from threats and violence they might face in other places or on the street.

But members of the community also had reason to be afraid of the police, and the fear reached inside the bars and clubs.

Murray Billett, a former member of the Edmonton Police Commission, came to Edmonton in the early 1990s and quickly realized there was a problem. “There was no real relationship of an official nature between the Edmonton Police Service and our fabulous community,” Billett said.

In 1981, nearly a decade before Billett came to Edmonton, the EPS had arrested about 60 people in a now-infamous raid on the Pisces Health Spa, a bathhouse frequented by gay men.

“It’s hard to explain to straight people how violated the queer community is when the bathhouse is raided, or when one of our bars is shut down,” Hagen said. “Because most straight people will never actually have to come up against that kind of fear.”

Billett has a unique perspective. As a gay man, he helped found a liaison committee to create an official relationship between the LGBTQ community and the police.

The first thing on the list was getting the police to stop criminalizing a lifestyle that was legalized a decade earlier. “We called the cops out, said, ‘What are you doing? This is absolutely unacceptable.’”

‘The city wasn’t safe for us’

Earlier this year, acting on an issue that had been years in discussion, Edmonton police Chief Dale McFee delivered a formal apology to the LGBTQ2+S community. The chief publicly acknowledged that Edmonton police had failed in their duty to protect a vulnerable population.

"Many people in this room will immediately recall the raids, the mistreatment during arrests and even public shamings,” McFee said. “These are just a few known and visceral examples.

"We know there is much more in the history of our service that is unheard, unseen and underground."

Watch the apology:

The apology from McFee was a triumph for many people who had been fighting for recognition from the police of their wrongdoing.

“Here we are, all these years later, with the most sensible, powerful, and compelling apology that I’ve seen come out of anyone, anywhere, ever,” Billett said.

Hagen was among those invited to attend the apology. For him, it was more than just an acknowledgment of past misdeeds by the police. It stood in for society as a whole.

“To hear an actual apology meant to me that finally a bit of the message had gotten through — that in fact, the only reason we need these places is because the city wasn’t safe for us.”

‘There will always be a need for spaces like this’

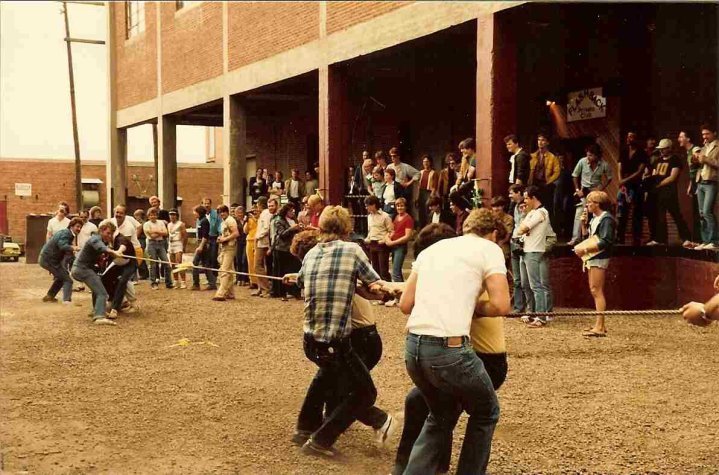

In April, The Edmonton Pride Festival Society announced it was cancelling the Pride festival. The festival and parade had been cornerstones of Pride month, a celebration of LGBTQ life that started as a protest for equal rights.

The cancellation came after the parade was halted by protesters demanding a more inclusive Pride experience for people of colour, including banning a police presence at the parade.

For Browatzke, owner of Evolution Wonderlounge in the Boardwalk building on 103rd Street, losing the Pride festival only highlighted the continuing need for gay bars.

“I think there will always be need for spaces like this,” he said.

“Nothing can compare to the first experience of a kid that’s just coming out that’s just 18, that’s always been a part of a minority that’s coming down and all of a sudden they’re like, ‘Wow, these are my people.’”

On the day that had been scheduled for the parade, Evolution hosted its own street party. For part of it, the bar suspended its liquor licence to accommodate a family-friendly drag show.

And while a bar that usually doesn’t allow minors is limited in its ability to be inclusive, it showed what more it could be.

“It's a family centre, it's a community centre,” said Browatzke, who has worked in gay bars for the past 20 years. “It's a dance club, it's an entertainment lounge. It's a little bit of everything.

“And certainly now that we are the only space like this in the city around, we need to be. And that can be super challenging, to try to be that one thing for everybody. But we do the best we can.”