June 1, 2018

Filmgoers headed to Saskatoon’s newly-opened Brighton multiplex today have no idea how good they have it.

Every variety of Coca Cola on tap. A perfectly-focused digital picture. Leather reclining loveseats you can reserve weeks in advance on your smartphone. And staying power.

“We’re here for at least 20 or more years,” said Landmark Cinemas CEO Bill Walker inside the 35,000-square-foot seven-plex last week.

But when the city’s first cinema, the Kevin, opened more than a century ago in June 1907, patrons were lucky to have even a semi-permanent home for “motion pictures.”

Cinemas came and went quickly in those days.

“I don’t remember them, other than hearing of them,” says Magic Lantern Theatres president Tom Hutchinson of Saskatoon’s earliest movie houses.

Movies had emerged a decade before as an “itinerant entertainment” — a footnote to the main attraction of travelling live stage performers coming to towns along the CP rail line. Short films depicted prize fights, fire brigade runs and bathing scenes.

It wasn’t until 1907 that, across Canada, “independent entrepreneurial showmen converted long, narrow, commercial store spaces into small theatres,” according to early Saskatchewan cinema historian Paul S. Moore.

“Seats were ordinary kitchen chairs with a plank running underneath them to hold them together,” Dalton Fisher, Saskatchewan’s first provincial theatre inspector, once told the Regina Leader-Post.

The West Side Theatre was a typically short-lived movie house. It opened in 1912 at the northwest corner of 20th Street West and Avenue C South — currently home to a Scotiabank.

The theatre was gone within five years. (The Roxy, opened two lots over in 1930, closed for a time but still survives today.)

Down the street, just west of Idylwyld Drive (where Freedom Functional Fitness stands now), the King Edward featured vaudeville acts along with films, as with many theatres of the time. But it barely lasted a year, becoming the first Saskatoon theatre to be destroyed by fire.

Theatres that didn’t quickly close often changed names or locations (sometimes both), which makes it difficult to keep some of them straight.

The Kevin, for instance, was almost immediately rechristened the Bijou (a common name for theatres at the time) and was later rebuilt at either the same location (Second Avenue South and 19th Street East) or a different one. Records also point to a Bijou on 21st Street.

'The latest "Wow"'

The Victoria has had many lives.

The theatre opened in 1913 on Second Avenue South at a cost of about $500,000 (in 2018 dollars). It was known for showing silent cowboy films, according to Saskatoon moviegoer Robert H. Thompson.

In 1930 the Victoria, like so many other cinemas, was rebuilt with equipment to show talkies — films with a synchronized soundtrack. It was renamed the Tivoli.

“Landmark has their reclining seats,” says Hutchinson of the most recent movie theatre tuneup to hit Saskatoon. “Everybody who puts a new theatre builds the latest ‘Wow.’ ”

The Beatles film A Hard Day’s Night debuted at the Tivoli in August 1964, attracting a line of around 100 young fans that extended half a block to 21st Street East.

A year later, the theatre facade was modernized and the cinema was renamed the Odeon. Its name was changed again in 1992, becoming the Paradise.

Today, people know the building as O’Brians Event Centre.

Songs, illustrated

By the mid-1910s, Saskatoon counted 14 silent movie theatres. Theatres typically showed five or six short films — comedies, dramas and nature films —during a night’s program.

Some cinemas like the Kevin also threw in what were known as “illustrated songs” between films.

Black and white images printed on glass slides, later hand-coloured, showed either illustrations or images of performers acting out the songs.

In November 1907, for example, between short films as varied as Police Dogs and How to Cure A Cold, customers paying 15 cents ($3.31 in 2018 dollars) to get into the Kevin could also see vocalist Percy Annable sing the illustrated tune Dear Old Georgia.

A month before, the same Master Annable performed April Morn “in little girl costume,” according to an ad in the Saskatoon StarPhoenix.

“This was over a hundred years ago, so everybody in the theatre sang along,” says Ben Model, a silent film composer, accompanist and historian in New York City.

Another Saskatoon theatre, the Dreamland, disappointed customers after advertising it would show photos of the sinking of the Titanic.

The photos turned out to be artist’s conceptions.

Anything but silent

Even before talkies, silent movies were never truly silent.

In 1895, when France’s Lumière Brothers showed their infamous film of a train pulling into a station, “they hired a local pianist to play folk tunes and what have you to accompany their films,” says Model.

The template was thus set for all North American movie theatres until the arrival of the talkies in the 1920s.

This piano-based silent film music was created by Belwin, Inc. in 1925 and is provided by The Silent Film Sound & Music Archive.

It didn’t always go synchronously.

“There was live music but photographs of the time show the piano, an upright piano, against the side wall so that the pianist is playing but not really able to see the screen,” says Model.

Instead of a carefully-arranged musical score, “it was really up to the local pianist to create the scores and to work from whatever music they had. If you knew a few pieces, you played them fast for chase scenes and slow for the love scenes.”

Only later, in the mid-1910s, would companies provide cue sheets to help guide the musicians.

“Ok, switch to a polka for minute and a half while this happens and then when the father comes in with the pitchfork, switch to Suspicioso No. 4. or whatever,” Model explains.

Bigger theatres could afford organs. The booming sounds also had the effect of drowning out noisy audience members.

The Daylight, opened in 1912 on 22nd Street (between Second and Third Avenues) and later known as the Paramount, put its own spin on things.

“The manager [Frank] Mily, as an added pitch for business, had a canopy erected to the right of the stage where he placed an all-female orchestra to accompany the pictures,” according to The History of Theatre in Saskatoon housed at the Saskatoon Public Library.

The Daylight liked to innovate. At 980 seats, it was one of Saskatoon’s largest movie houses. In January 1914, the theatre showed the longest film program the city had seen to date.

A reel of film ran anywhere from 12 to 15 minutes. That month the Daylight’s program stretched to eight reels, including a one-reel film about a man-eating tiger.

The Empire strikes back

When it came time for Saskatoon to show the blockbuster film of the silent era, the Empire was the theatre of choice.

Completed in late 1910, the theatre stood beside the Empire Hotel at the corner of Second Avenue South and 20th Street East.

Today the corner is home to the Lighthouse Supported Living shelter.

Built as a legitimate theatre venue but doubling as a cinema, the Empire had a 24-foot-deep stage, two balconies, 10 dress boxes, supporting pillars upholstered and draped in gold plush and a large pit for an orchestra.

Behind the proscenium arch stood a 23-foot-by-30-foot asbestos curtain. The example below, photographed in 1916 at the Majestic Theatre in Biggar, Sask., gives an idea:

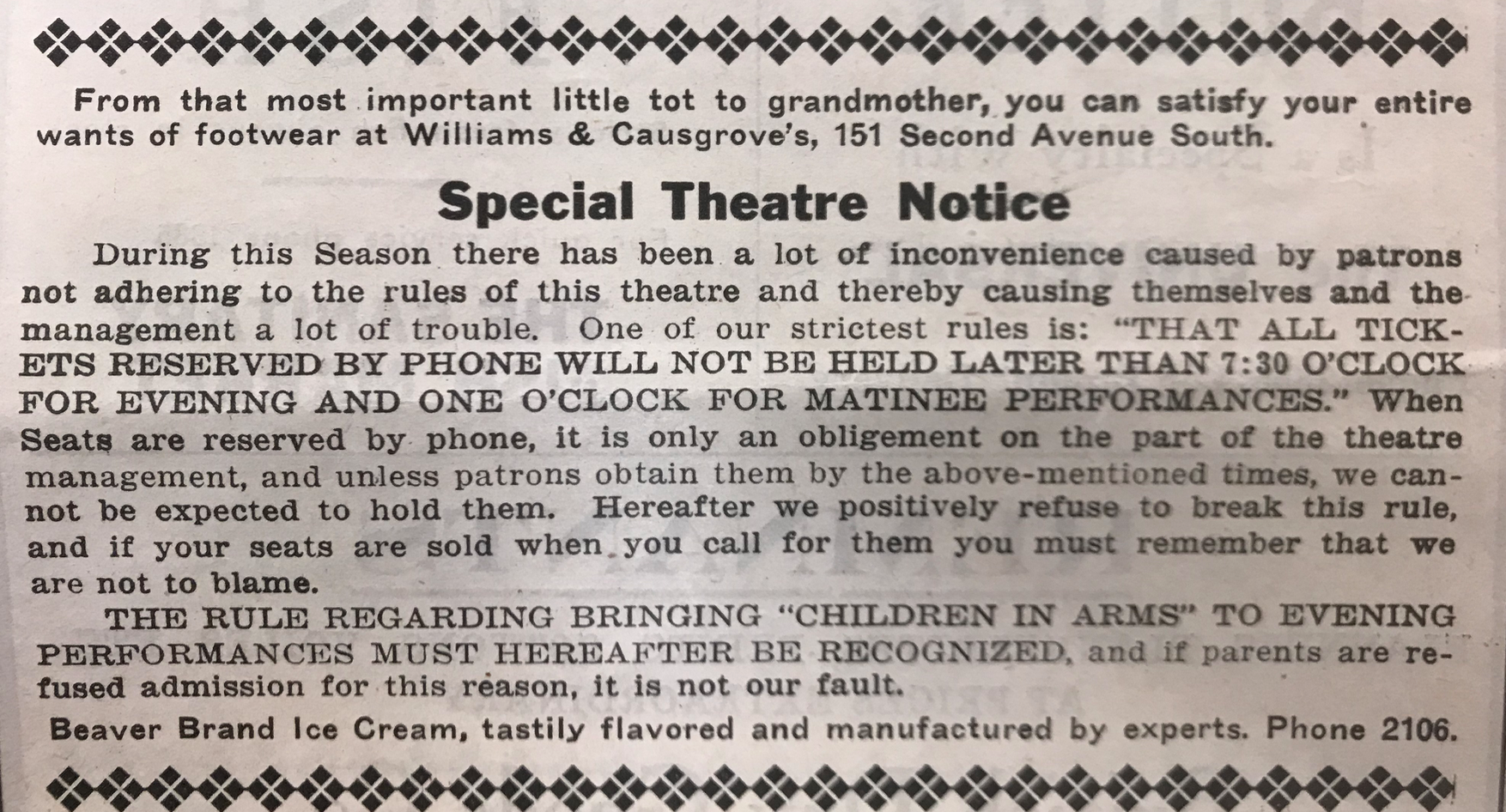

Strict house rules governed the Empire’s ornate setting. Saskatoon’s modern-day theatres may be competing for the moms and strollers crowd, but in the early 20th century a program for the Empire warned mothers against bringing their “children in arms.”

“If parents are refused admission for this reason, it is not our fault,” the program read.

Residents connected to Saskatoon’s automatic phone system could phone the theatre to reserve tickets, not unlike the online reserved seating systems plugged today.

Tardiness was punished. Tickets reserved for evening performances that went unclaimed by 7:30 p.m. were fair game for other customers.

The Empire hosted many touring shows, including the Dumbbells, a Toronto blackface troupe that sold out crowds.

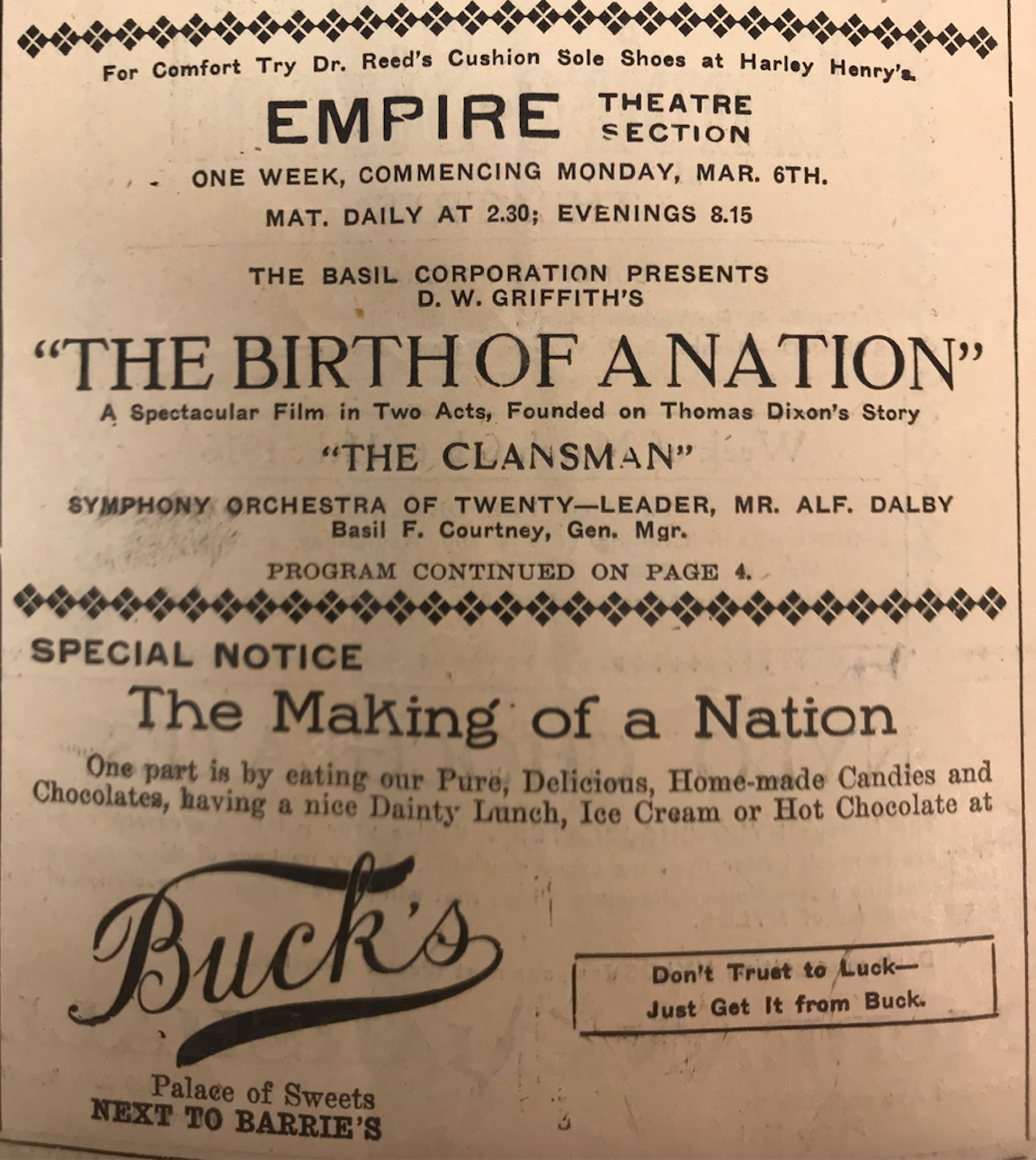

For one week in March 1917, the Empire screened director D.W. Griffith’s landmark, feature-length film about the Civil War and the American south, The Birth of a Nation.

Today, the three-hour film’s negative depiction of black people and its portrait of Ku Klux Klan members as valiant heroes make it a problematic historical document.

But at the time, “sad to say, believe it or not, it was a huge hit,” says Model.

The film’s epic battle scenes and tense cross-cutting between scenes marked important advances in filmmaking.

And Birth’s specially arranged film score — composed by Joseph Carl Breil and performed at The Empire by a 20-piece orchestra led by Alf Dalby — was a “big change” in film exhibition, says Model.

“It was one of the first films to have musical accompaniment by an orchestra,” and one where distinct themes were tied to certain characters, Model says.

“The sound of a full symphony orchestra had such a huge impact for the film. And the film was such a success that it legitimized going to the theatres for all people.”

In the Nickelodeon era, before feature-length films like The Birth of a Nation, movie theatres were places of escape for the working class, immigrants and factory workers.

“Certain people wouldn’t be caught dead in a movie picture house,” says Model. “But if the films were better and the proper music was there, that kinda classed up the whole thing.”

Live orchestral accompaniment became the norm for as many silent movie theatres as could afford it.

But silent film ultimately was an art form with a short shelf-life, all but obliterated by the talkies. By 1930 Saskatoon already featured five theatres, including the Roxy, capable of playing sound-synced films.

“Silent presentations of the silver screen are a thing of the past there, and there are very few cities which can make the same boast,” read an advertorial in the StarPhoenix.

The Empire lasted far longer than all the other early Saskatoon movie theatres.

It stuck around for 12 years as a talkie theatre renamed the Hub before eventually being torn down in 1958 to make room for more parking at the hotel.

‘A form of audience preservation’

Today, one group in Saskatoon is ensuring silent films are not completely forgotten.

Beginning in 2010 with Fritz Lang’s dystopian sci-fi fable Metropolis, the Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra has performed live scores twice a year alongside silent films.

Last month, the time-hopping screening was a triple bill: a Felix the Cat cartoon from 1927 followed by two Charlie Chaplin shorts from a decade before.

Music director Eric Paetkau led a group of around 15 musicians in a small space in front of the screen at the Roxy.

Silent film in action

“It’s a bit of an undertaking for us, especially me,” said Paetkau before the show. “I have to line up the exact tempo with what is supposed to be playing on the film.

“But if we’re a bit behind, I have my cues written in. ‘Oh, Charlie Chaplin takes his hat off here.’ Oh, we’re a bit behind? Gotta speed up slightly, then I gotta slow done a bit. It’s always this little juggling act that we do but it’s worth it for sure. People love it.”

Model, the silent film accompanist in New York, composed the music played by the SSO.

“I feel like, when the lights go out, I’m working for Chaplin or Keaton or Doug Fairbanks or whoever,” said Model.

Though the music is front and centre, “I think of what I do as a form of audience preservation,” Model added.

“There’s something about knowing, out of the corner of your mind, that there is a person at the front of the room creating the music you’re hearing.

“It makes your brain sit up in the seat a little bit more."

In his next feature about Saskatoon’s movie theatre past, Guy Quenneville will turn to the city’s most storied theatre from the sound era, the Capitol. Torn down in 1979 to make way for the downtown Scotia Centre mall, the Capitol lives on today in fragments scattered throughout the city. Do you remember the Capitol? Share your memories with Guy at guy.quenneville@cbc.ca