December 2, 2019

This story is part of Vape Fail, a CBC News series examining some of the policy failures that led to the adoption of vaping as a smoking alternative and the resulting consequences.

Most Canadians don't smoke.

Yet Canada has chosen to implement a nationwide smoking-cessation strategy to make nicotine vaping devices as accessible as possible.

It was an unusual public health decision for regulators to deliberately craft a law to encourage the sale of an addictive product.

The federal government's goal was "to strike a balance between protecting youth from inducement to nicotine and tobacco use, while allowing adult smokers to legally access vaping products," Health Minister Jane Philpott told a Senate committee on April 12, 2017, as the legislation was being debated before final approval.

The resulting law, which came into effect in May 2018, means vaping devices have fewer restrictions than tobacco and cannabis under Canada's Tobacco and Vaping Products Act.

Unlike cannabis, vaping devices can be sold anywhere, and unlike tobacco, there are no warning labels required on packages, and the sale of fruit flavours is allowed.

Canada's vaping approach was based on a hypothesis — that the minority of Canadians who still smoked might switch to vaping.

Federal health officials knew when they drafted the law that they did not have definitive evidence that e-cigarettes were effective at helping people quit smoking.

And today it's becoming clear that the utopian post-tobacco vision is not materializing the way it was imagined.

"The majority of smokers do not switch," said Dr. Charlotta Pisinger, a leading researcher on tobacco prevention at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. "It was wishful thinking. The smokers didn't do as we wanted them to do."

Instead of abandoning cigarettes, many smokers have added vaping to their nicotine habits, becoming dual-users.

And even though the law tried to protect teens, through advertising and age restrictions, it hasn't worked. The latest statistics show that about a quarter of high school students across Canada are vaping.

Add to that a mysterious and deadly vaping illness, along with new research showing vaping poses unique risks for organ damage and chronic disease, and some of the same health advocates who promoted vaping are now calling for a course correction in Health Canada's policy.

"We opened it up too wide," said David Hammond, a professor of public health at the University of Waterloo who researches tobacco-control policies. "We still have very few regulations on e-cigarettes."

As they drafted the new vaping laws, health officials also appeared unconcerned about the looming spectre of Big Tobacco — with its devastating history of death and disease — moving prominently into the vaping sphere.

"It was kind of like the standard public health precautionary principles got thrown out the window," said Andrew Pipe, a heart specialist and smoking cessation physician in Ottawa.

"It's perplexing because otherwise sentient, thoughtful people allowed this to happen."

Everything is safer than a cigarette

The evolution of Canada's vaping policies was based on a theory of relativity.

The battery-operated heating devices were novel consumer products that deliver nicotine and other unknown compounds into the lungs.

But instead of being judged in isolation, e-cigarettes have always been measured in relative terms — how safe they are compared to combustible cigarettes.

And because almost every other consumer product is safer than a cigarette, vaping devices came on the market already bearing a healthy halo.

"It is the wrong way to look at it," said Pisinger, who realized early on the risks of comparing vaping to cigarette smoking.

"We have been so focused on smokers and how to make it easy for smokers to quit, or reduce their harm, that we have forgotten to take care of the rest of the population."

The emergence of e-cigarettes should not have caught tobacco-control experts by surprise. The tobacco industry has been working on a novel way to offer nicotine to their cigarette customers for decades.

Industry documents released through the courts show tobacco executives imagining an invention that would "act as an acceptable alternative to both cigarettes and quitting."

"Perhaps we could develop cigarettes that would not have to be lighted with a flame … that would burn without smoke … and that would not leave butts. Ridiculous? Perhaps," an industry executive wrote in 1976.

All of the early industry prototypes failed in the market. But by 2006, a new version of Chinese-made "nicotine inhalers" began to be imported and sold in the U.S. They simulated the look and feel of a cigarette, but used a battery to create a nicotine vapour.

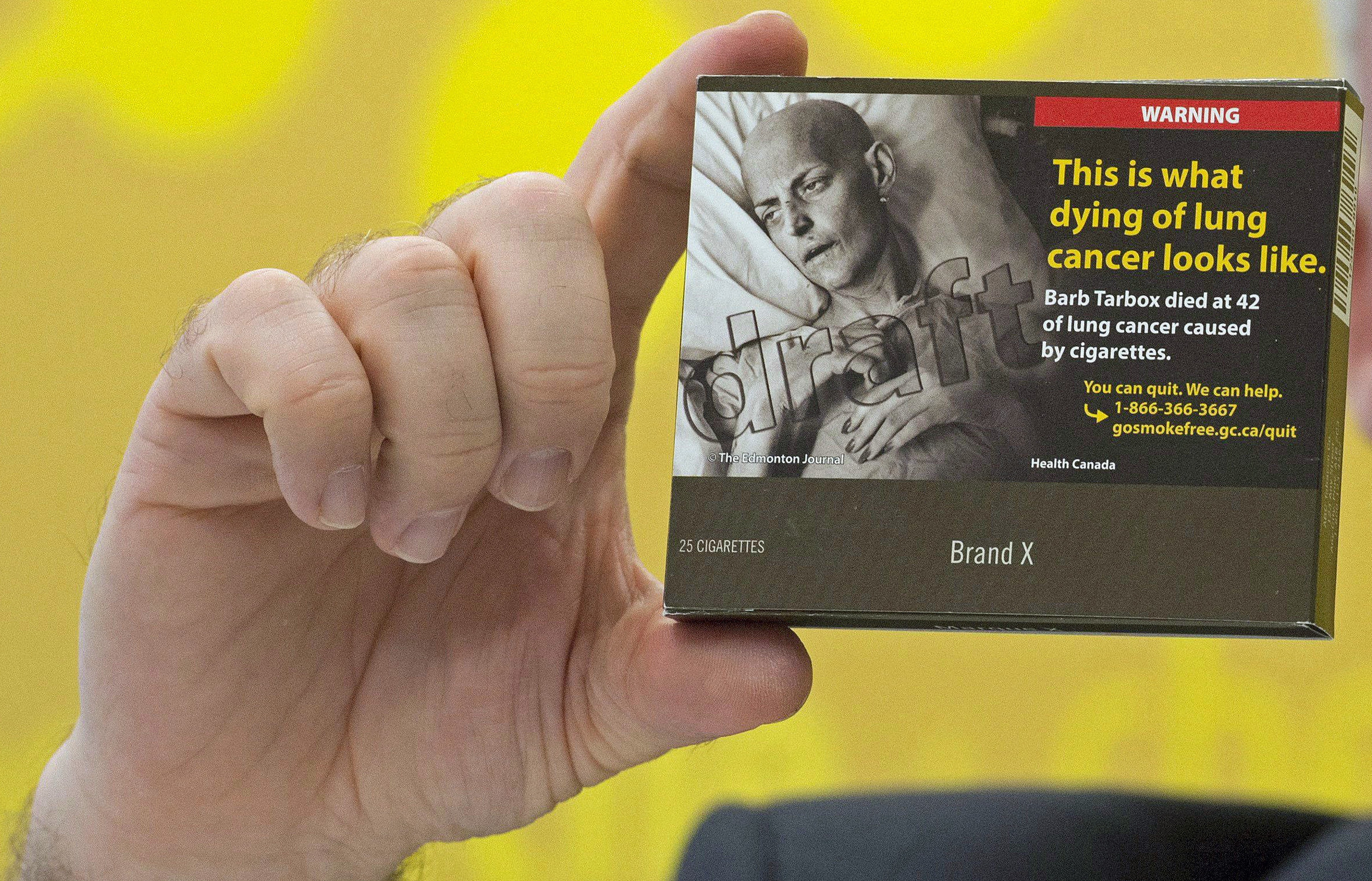

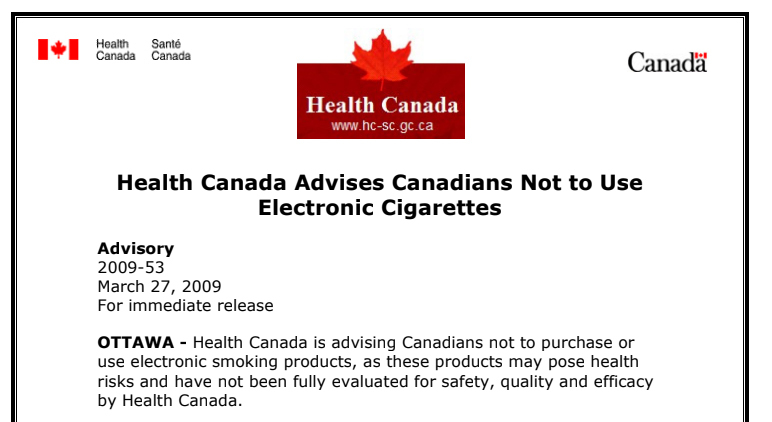

When those first e-cigarettes appeared in Canada in 2009, Health Canada's instinct was to slam the door shut.

The agency issued a public warning to Canadians "not to purchase or use electronic smoking products, as these products may pose health risks and have not been fully evaluated for safety, quality and efficacy by Health Canada."

In the beginning, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also tried to crack down by blocking imports of e-cigarettes, calling them "unapproved drug/device combinations" that would need special health approval and licensing.

But when two U.S. companies sued the government, a district court in D.C. ruled the FDA did not have jurisdiction to regulate e-cigarettes because they were not being marketed as a treatment for nicotine addiction. Instead, the judge determined the marketing was aimed at "encouraging nicotine use."

The FDA decided not to appeal, and instead drafted legislation to regulate e-cigarettes as tobacco products that need FDA approval. That regulation process is still unfolding.

Although nicotine e-cigarettes remained technically illegal in Canada, small vape shops selling flavoured vaping juices began popping up across the country. Canadians were also able to buy e-cigarettes online.

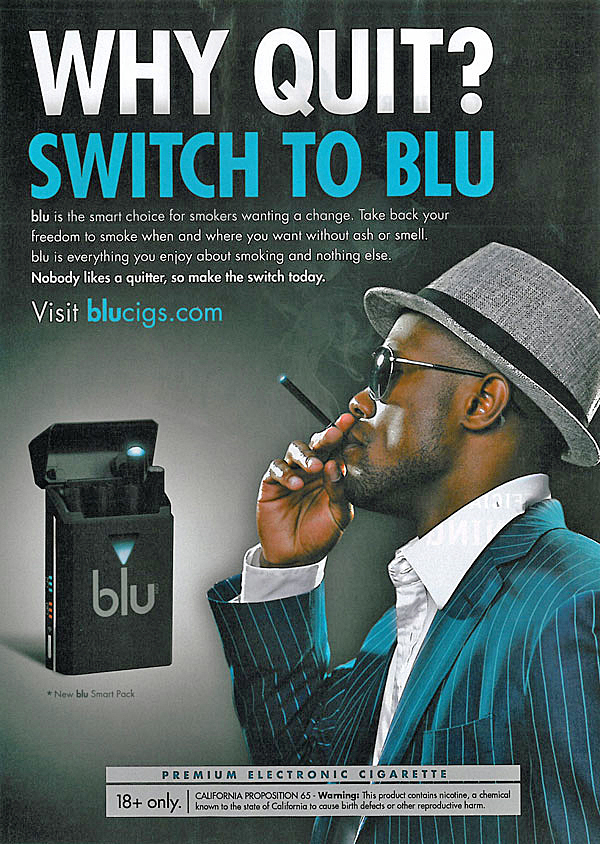

The first e-cigarettes were advertised in magazines and online as a way for smokers to keep smoking with greater freedom — on airplanes, in bars and other places where cigarettes were banned.

An e-cigarette advertisement published in 2011 asks, "Why Quit?" and urges smokers to use the e-cigarette to "take back your freedom to smoke when and where you want without ash or smell."

When tobacco prevention researcher Charlotta Pisinger saw that ad she had a flashback to the tobacco industry's campaign several decades earlier promoting the benefits of switching to "light" cigarettes.

"Suddenly I could see it in the historical perspective," the researcher said. "And we knew from light cigarettes that it was a public health disaster because they undermined smokers' wish to quit completely."

Andrew Pipe, the heart specialist in Ottawa, used the "Why quit?" ad in seminars at medical conferences five years ago to warn about the ways tobacco companies could use e-cigarettes to promote smoking.

He told his audiences it would be an opportunity for the tobacco industry to push back against the social forces that had made smoking increasingly unacceptable in public.

"There was a disinclination to thoughtfully regulate these products," he said.

The Blu brand, featured in the ad, is now owned by Imperial Brands, which acquired it in 2014, as part of a merger. A spokesperson for Fontem Ventures, a subsidiary of Imperial, said the company can't speak to the motivations of ads created before the acquisition.

"In regards to this specific advertisement and messaging, this is not the type of language that we would use."

No proof, but plenty of faith

From the start, vaping companies were given a free pass on the health effects of their products. The industry was never pressured to prove that e-cigarettes were anything more than recreational devices. And, in an odd reversal of marketing roles, public health officials began promoting the health benefits of vaping.

In 2015, Public Health England famously announced that e-cigarettes were "95 per cent safer than cigarettes" based on a review of the evidence. That endorsement was reported in headlines around the world.

But the "95 per cent safer" claim was immediately criticized in an editorial in The Lancet as having an "extraordinarily flimsy foundation," which was largely based on "the opinions of a small group of individuals with no prespecified expertise in tobacco control."

The editorial also points out that some authors had potential conflicts of interest with the e-cigarette industry.

"It's as if this was scientifically established. It's not," said Richard Stanwick, the chief medical health officer for Island Health in Victoria. "It's just opinion."

Still, the U.K. pronouncement became one of the main pieces of evidence cited by public health officials to support a pro-vaping stance.

"It went all over the world, and it confused many public health people," said Pisinger, who was doing her own research on the health effects of vaping.

A year earlier, Pisinger published the first systematic review of the studies into the health effects of e-cigarettes and concluded the evidence was so weak and marred by severe conflicts of interest that no firm conclusions could be made about safety.

She updated that review for the World Health Organization in 2015, stepping up the warning by concluding: "Even though no firm conclusions can be drawn on the safety of e-cigarettes, there is an increasing body of evidence indicating harm."

"I felt a great responsibility on drawing these conclusions," she said. "But I felt I had to focus on the public health and not only on smokers."

But she was a lonely voice amid the rising chorus of experts trumpeting the end of cigarette smoking through e-cigarettes.

"I felt very much isolated."

Early signs of youth vaping

As the pro-vaping forces gathered steam, there was evidence from all over the world that young people were experimenting with e-cigarettes.

In 2013, the CDC reported "e-cigarette experimentation and recent use doubled" among middle and high school students during 2011-2012.

Two years later, the CDC reported a 900 per cent increase in teen e-cigarette use, prompting the U.S. surgeon general to announce that it had become "a major public health concern."

The same pattern was emerging in France, Poland and Canada, where a 2014 survey showed 16 per cent of young people reported trying e-cigarettes. And the majority of them were "never smokers."

By 2015, Dr. Richard Stanwick in Victoria was so concerned about youth vaping that he wrote an urgent position paper for the Canadian Paediatric Society urging Ottawa and the provinces to create regulations that would restrict the sale and marketing of e-cigarettes.

He said he felt dismissed as a "nervous Nellie."

At the time, e-cigarettes with nicotine were still illegal in Canada. But enforcement was weak.

"We know that youth are using these products," Hillary Geller, an assistant deputy minister at Health Canada, told the Commons health committee in October 2014.

"In some cases, marketing appears to be targeted at youth and young adults through the use of flavours and certain promotional techniques that glamorize their use."

Students in a Grade 9 health class at Richview Collegiate in Toronto talk about the marketing and consequences of vaping.

Health Canada's Dr. John Patrick Stewart testified that the addictive potential of e-cigarettes was unknown, and that they "may be as addictive as, if not more addictive than cigarettes."

Another Health Canada official, Suzy McDonald, told the committee: "The bottom line is that we do not have the evidence yet to demonstrate that these products definitively help folks quit smoking."

Despite that uncertainty, Health Canada did not require the vaping industry to provide any evidence e-cigarettes are safe and effective at helping smokers quit.

As a heart specialist who works with patients on smoking cessation, Pipe was growing increasingly concerned about the lack of evidence supporting e-cigarettes.

"The degree to which people became enthralled with the harm-reduction approach, I think, led to a suspension of critical thinking."

Big Tobacco is also Big Vape

As they designed a policy to bring electronic cigarettes into the marketplace, the policy-makers ignored the signs that Big Tobacco had become Big Vape.

Beginning in 2010, the major international tobacco companies entered the e-cigarette industry by acquiring smaller companies and developing their own devices.

It's almost evangelical in this movement that the vape industry is the one that's going to solve the cigarette problem.

By 2018, they dominated the market, a development tracked by Annalise Mathers at the University of Toronto.

"I think they were just kind of lying in wait in terms of when to start to acquire these products, kind of slowly and silently," she said.

"The TTCs [transnational tobacco companies] really wanted another opportunity to establish their legitimacy, to establish their place at the table in terms of policy and regulation moving forward. So I think this has to be viewed in terms of a very long-term business strategy."

- The hope of vaping as a safer alternative to smoking is fading. We explore why

- The science behind why vaping is becoming so popular in Canada

The World Health Organization warned countries that the increasing involvement of the global tobacco giants in the marketing of e-cigarettes "is a major threat to tobacco control."

In Victoria, Richard Stanwick watched the involvement of Big Tobacco with growing concern, even though other smoking-cessation experts still believed that vaping could end tobacco smoking.

"It's almost evangelical in this movement that the vape industry is the one that's going to solve the cigarette problem," Stanwick said. "The rest of us really see the big engagement of Big Tobacco."

Canada's Tobacco and Vaping Products Act came into effect in May 2018, just three months before the arrival of JUUL, a radical innovation in e-cigarettes.

Representatives from the vaping giant made a courtesy call to Health Canada in August to introduce the new devices the company was about to launch in Canada.

The sleek JUUL device could be easily hidden from parents and teachers. And the tiny cartridge filled with flavoured nicotine salts gave users a hit of nicotine that rivalled a traditional cigarette.

In September 2018, the JUUL juggernaut landed with force.

Teenage vaping surged to the point where some schools took the doors off bathrooms, and teachers were seizing devices from students.

"I think this is what is most frustrating," said Stanwick. "We had a chance to get ahead of this product."

Health Canada helps market e-cigarettes

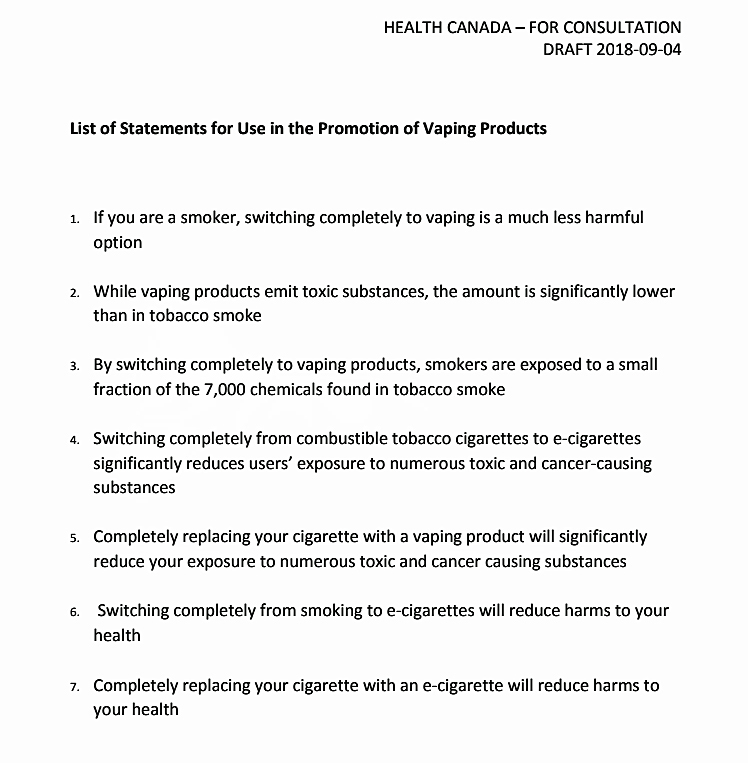

Meanwhile, Health Canada officials were working on ways to promote vaping to smokers by developing a series of health claims the industry could use to market the products.

In early September 2018, Health Canada sent a letter inviting industry officials and tobacco-control advocates to comment on seven statements, all variations on the claim that vaping is safer than smoking.

The consultations were not made public. But the federal government did make an announcement at a World Trade Organization committee meeting last year that it is developing regulations "to allow for certain statements to be used in the promotion of vaping products that compare the health effects of vaping to smoking."

(Health Canada told CBC News in an email this week that the proposal for comparative health statements is still under consideration.)

"It floored me, and got me busy writing comments," Neil Collishaw, research director with Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada, said of his reaction to learning about the consultations.

He wrote a detailed response to Health Canada, concluding: "Rather than seeking to create a series of ill-advised comparative risk statements, Health Canada is encouraged to take effective action to mitigate serious public health problems associated with e-cigarette use."

Tobacco-control advocate Stanton Glantz, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, warned Health Canada that the proposed health claims "could be misread by consumers and potential consumers as indicating that e-cigarettes are safe."

Fontem Ventures, which markets the Blu vaping device, said in a submission that it "applauds" Health Canada for the initiative.

The company suggested several revisions and also advised Health Canada to replace the term "e-cigarette" with "vaping products."

"Although we suggested minor revisions to the wording of these statements, we strongly support the concept of public authorities making scientifically substantiated statements that allow adult smokers to make an informed choice about how they consume nicotine," Fontem Ventures spokesperson Ross Parker told CBC News in an email.

Big Tobacco at the policy table

So, in a stunning resurrection from the ashes of a public health disaster, Big Tobacco is back at the health policy table.

After decades of fierce legal and legislative battles, the tobacco industry and health policy-makers are now on the same side, promoting a nicotine product aimed at harm reduction.

Timothy Dewhirst, a marketing professor at the University of Guelph, said it's not harm reduction if vaping ends up drawing in new users to nicotine or if smokers add vaping to their cigarette habit and ultimately fail to quit.

"I think there's overall a net harm," he said, pointing out that the goal of complete smoking cessation is not a good business strategy for the tobacco industry.

"Their objectives are different than the public health community's objectives," he said. "It's not in their interest to have people successfully quit altogether."

'Bad news on all fronts'

At this point, tobacco industry projections still emphasize traditional cigarette sales as the core of their business.

"Cigarette sales around the world have been quite stable and I don't think that those will be going down anytime soon," said Annalise Mathers, of the Ontario Tobacco Research Unit at the University of Toronto.

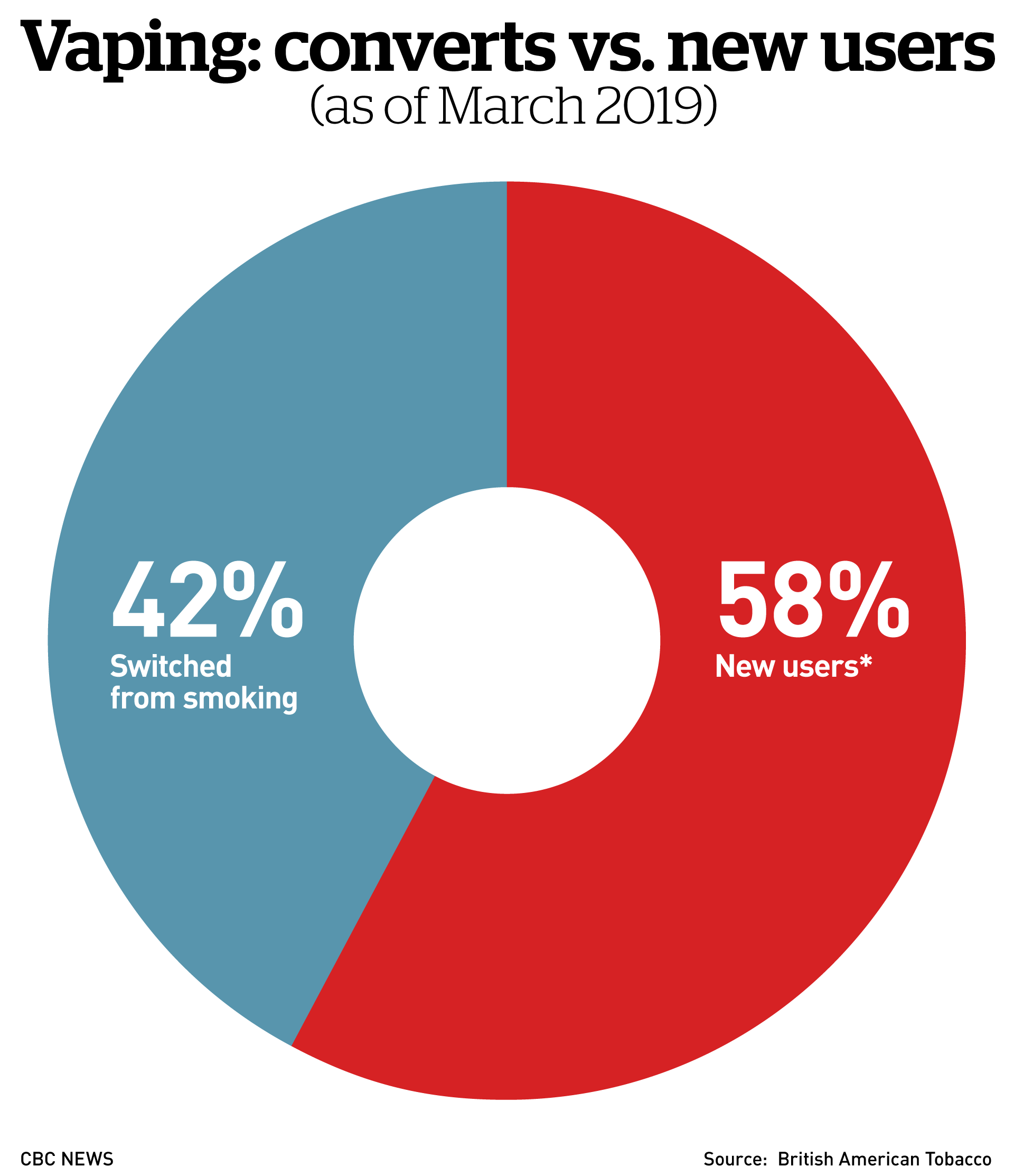

Industry documents reveal that rather than switching completely to vaping, many smokers are using both e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes.

It's also becoming clear that many vapers are new to the nicotine habit.

"E-cigarettes and reduced-risk products are kind of seen as a nice complement to maintain that core business, which is nicotine," Mathers said. "Keeping people addicted to nicotine."

At the same time, an entirely new generation of teenage nicotine addiction is taking hold.

University of Waterloo professor David Hammond tracks youth vaping trends through a survey of thousands of teenagers in Canada, the U.S. and U.K.

Last year, his research picked up the first signs of a vaping surge in Canada following JUUL's arrival. This year, the numbers have gone up again.

"Vaping has almost doubled again among youth," he said. "What we're seeing is more frequent vaping. We're seeing more and more ... that they feel they're addicted to vaping.

"So, essentially, it's bad news on all fronts in terms of youth."

Add to that the continued lack of evidence that vaping helps smokers quit.

"There are three or four good review studies that show that these things are 85 to 95 per cent ineffective," said Andrew Pipe, the heart specialist in Ottawa. "And that's generally not appreciated."

CBC News asked Health Canada for a chance to interview the minister or a department official about the agency's vaping policy, but no interview was granted.

On Nov. 21, shortly after she was sworn in as Canada's new health minister, Patty Hajdu was asked by reporters what she planned to do about youth vaping.

"I will say, as the mother of two now grown boys, I can imagine the stress this is giving to parents all across Canada," she said.

"So, we have to do more. I'll be speaking with stakeholders. I'll be speaking with my colleagues about what stronger actions we can take to protect young people from the effects of vaping but also the effects of advertising that tries to convince them that this is a healthier choice."

For Charlotta Pisinger, the Danish researcher, all of the commotion about vaping has obscured the fact that smokers already had the tools to help shed their nicotine dependency. Smoking rates have fallen dramatically over the past several decades.

In 1965, about half of the population smoked. Fifty years later, the smoking rate in Canada was down to about 15 per cent.

She is concerned that encouraging smokers to vape assumes that they can never be fully free of nicotine.

"Is risk reduction the aim? Isn't our aim to get smokers to breathe clean air?"

Pipe has some even darker fears.

"My biggest fear is that we are going to go back to a time where we see a significant, if not a majority of the population dependent on nicotine as was the case with cigarettes in the '50s and '60s," he said.

"Are we going to see history repeat itself?"