When people used to ask Josée where she was from, she didn’t really know what to say.

Though she identifies as Algonquin, she didn’t grow up on a First Nation.

But through movement, she says she’s found an answer to that question, in more ways than one.

“I made that decision to start dancing because I wanted to have some substance behind being able to say, yeah, I'm First Nations.”

Now, the 36-year-old describes dance as the basis of her entire life, a tool to reclaim space on her ancestral Algonquin territory.

“Without dance I would [not be] my true self,” said Josée from the backyard of her home in the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation, which sits on the shores of Golden Lake and the Bonnechere River in Renfrew County, west of Ottawa.

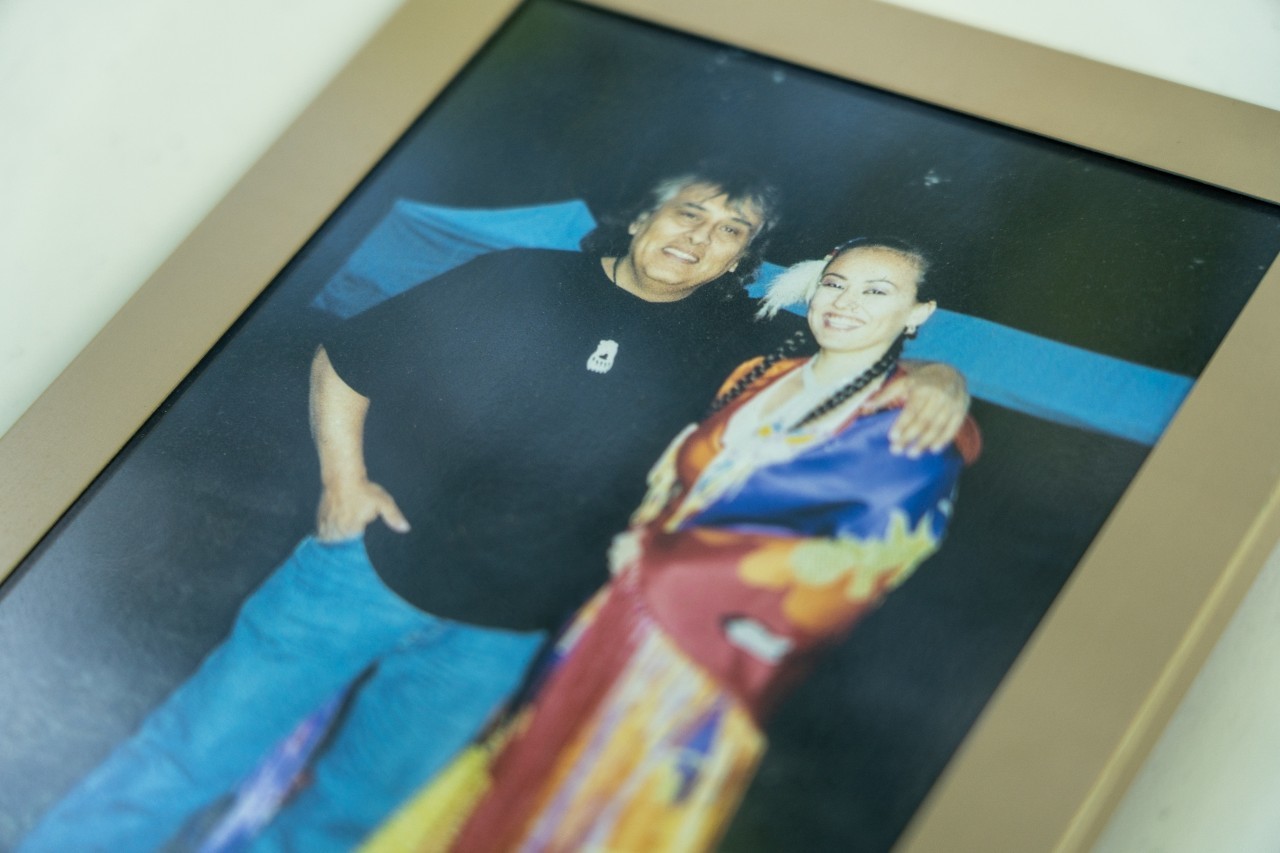

Josée doesn’t like to use her last name because to her it represents colonization. Her father is a Sixties Scoop survivor who was taken off the reserve and raised by an Irish family in Arnprior, Ont.

Group petitions PM for national apology to 60s Scoop survivors

Sixties Scoop class action settlement to move forward after delays

He later reconnected with his brothers and sisters but missed meeting his biological mother by one year before she died.

Josée says though she grew up mostly in the city, through movement she's found her way back to her First Nation

Josée says the severed family tree and intergenerational trauma left her mostly on her own to discover her Indigenous roots.

That journey followed a winding and intricate path but ultimately led her to an opportunity that she describes as an “artist’s dream.”

Not a ‘conventional life’

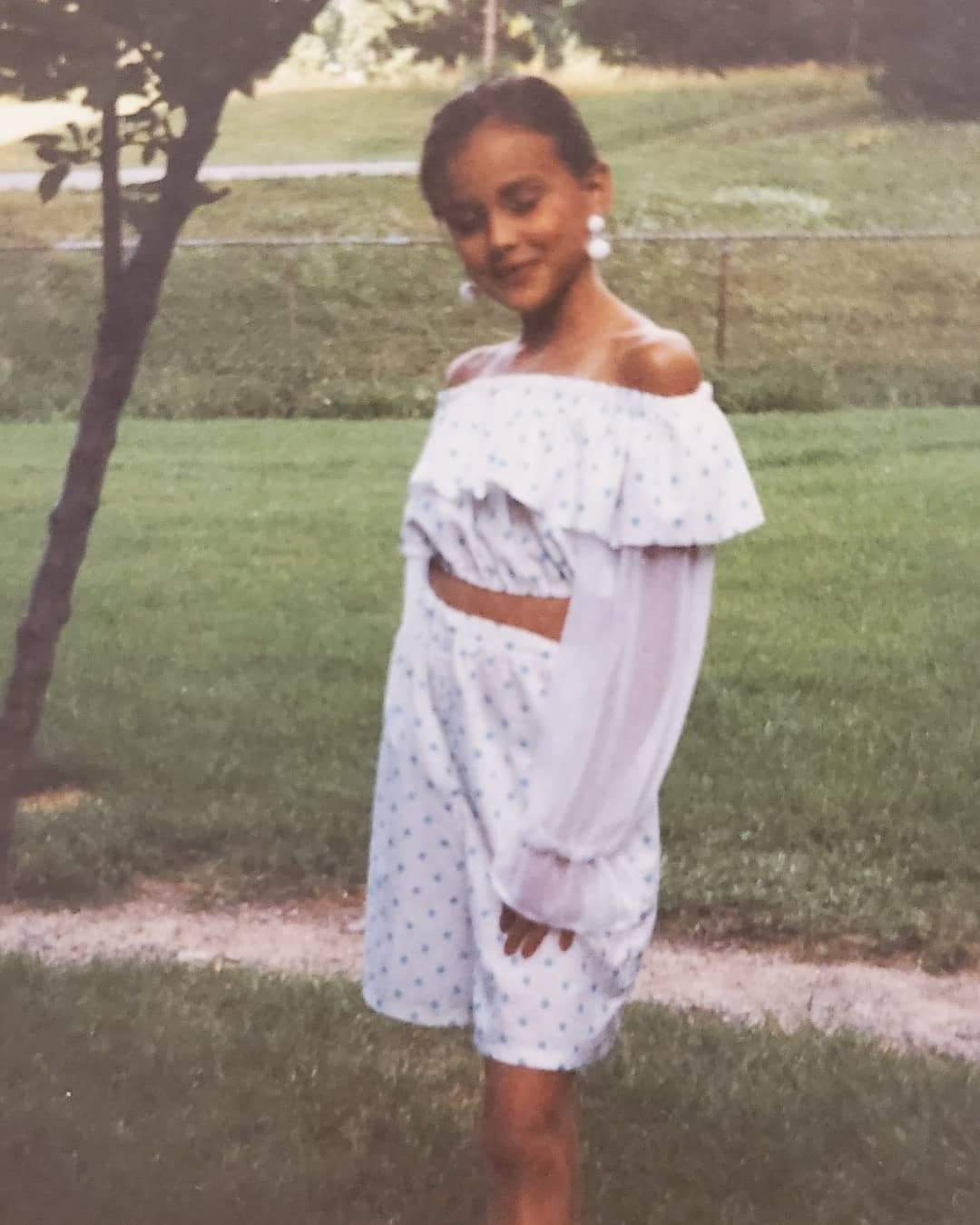

Growing up in Toronto with her mother, who is a Jehovah’s Witness, Josée said her love for dance began with gymnastics. She spent her adolescent years modelling and even attended flying trapeze camps at a circus school in the city.

“I did not have a conventional life at all,” she said.

She spent part of her summers with her father in Pikwàkanagàn and still remembers the first time she experienced a powwow.

“I saw healthy, happy, resilient, strong, beautiful Native people of all different Nations who spoke their language, who knew what families claimed them, who knew what communities claimed them.”

“And then I started to realize that, like through my father's heritage, this was the community that I was connected to. And that was very life-changing for me,” she said.

In her 20s, Josée decided to travel the powwow trail, dancing at events across the continent during the summer months. She began as a fancy shawl dancer, which she describes as “a very spastic style of dance,” that’s fast-paced with lots of kicks and spins, later learning jingle dress dancing, and along the way learning how to make her own regalia.

With those two styles and other forms of dance she’s picked up over the years Josée started offering powwow workout classes, which she calls "pow wow step groove" — something that has continued virtually throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Using dance to express emotions

At 23, Josée went to the Odawa powwow, dancing for the first time. It was there that she met her son’s father.

Now, Little Thunder is 11 years old and said he too uses dance to express his emotions.

“So whenever I dance, I always have this feeling of joy doing it. It's one of my favourite things to do in the summer before Covid,” Little Thunder said, disappointed by the cancellation of these events.

Josée first introduced Little Thunder to powwow dancing when he was three years old but said the main goal has always been to teach him the truth about their history.

A platform to be heard

That dark past is one that Josée will also be sharing with a film project at the National Arts Centre (NAC), where she recently began a residency as a visiting dance artist. Her goal is to explore Indigenous women’s sexuality through dance, looking at the impact of colonialism and misogyny, on her own terms.

“As an Indigenous woman, I have to think three, four times walking on the road. We do have a target on our back. It's not a secret anymore,” she said.

The project is still in the early stages, but Josée plans to highlight the acknowledged genocide of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada and explore truths that she says people are uncomfortable accepting.

“Conversations aren’t working. The research and the reports, they seem to be at a stall,” she said, adding that she’s grateful the NAC has given her a platform to be heard.

“That's reparations. That’s reconciliation.”