July 21, 2019

When Sheree Fertuck's truck is found abandoned, suspicions grow around what happened to her. The Pit is a CBC investigative podcast series that uncovers the story of a woman's mysterious disappearance — and of the gravel pit that could still hold clues to finding her. Read what is known about suspected murder victim Sheree Fertuck, her detailed history with the man accused in her death — and why he is proclaiming his innocence from behind bars.

- Listen and subscribe to the podcast at cbc.ca/thepit

- Explore the gravel pit — the last known whereabouts of Sheree Fertuck — in a 360 video experience.

Dec. 7, 2015. In a Saskatchewan farmhouse behind a small cluster of trees, surrounded by fields of prairie farmland, Sheree Fertuck sat down for lunch with her mom, Juliann Sorotski.

Neither of them knew it would be the last time.

After the meal, Fertuck walked back to her semi-trailer parked outside and pulled herself up into the driver's seat. The truck was essentially her office, since she spent most of her days there.

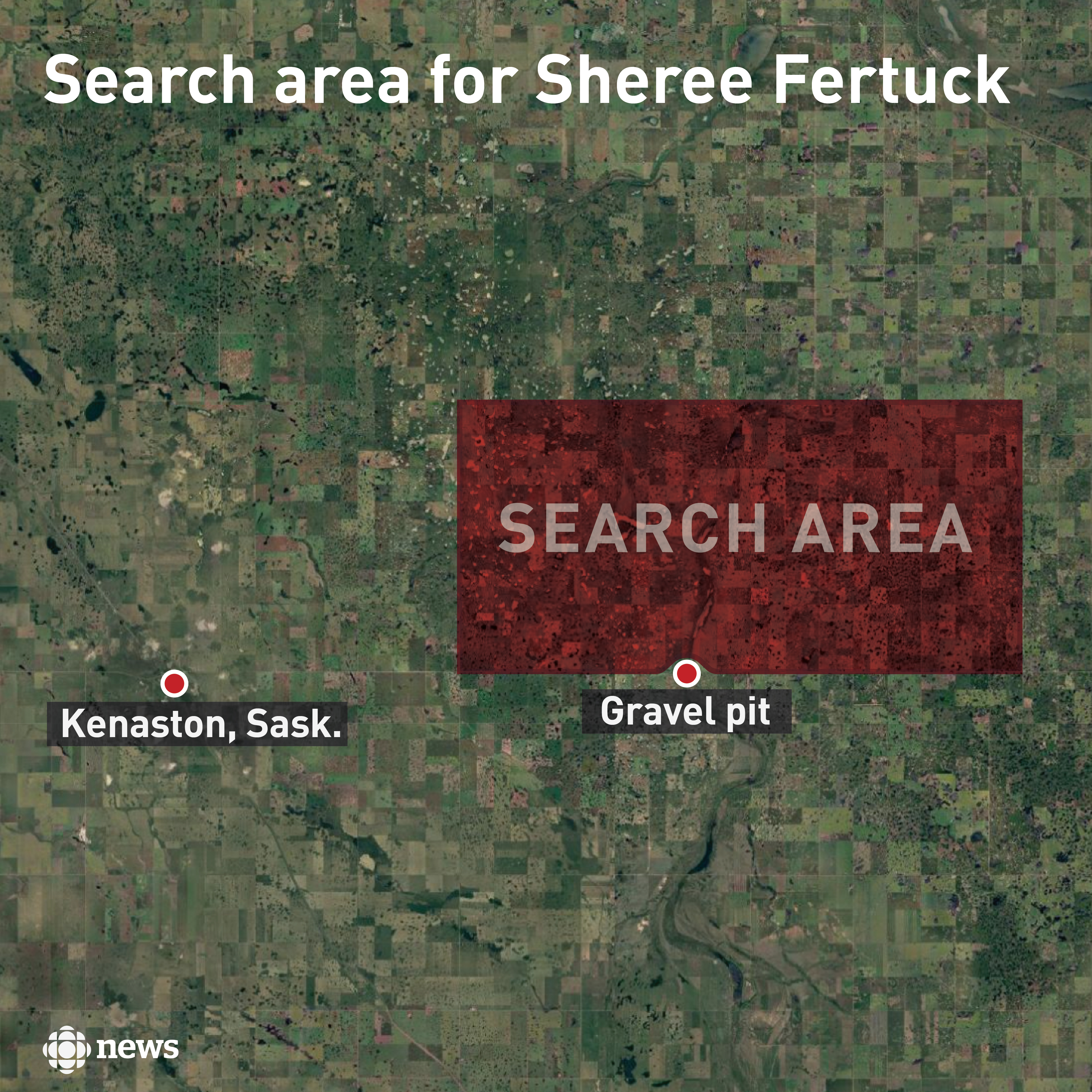

Fertuck, 51, was a gravel hauler. She loaded crushed earth into her semi, then moved it wherever it was needed to cover the rural roads near the small town of Kenaston. Fertuck lived in Saskatoon, but often stayed at her mother's house just outside of Kenaston when work was especially busy.

Fertuck guided the heavy vehicle away from the house and down the quiet highway, passing abandoned farmhouses and expansive fields on the way to the nearby gravel pit.

Neighbours driving past on Highway 15 that day saw Fertuck's truck parked down in the pit. As it got dark, the semi was still there, its headlights shining into the cool winter night.

When Fertuck didn't return for supper, Sorotski started calling around.

"I didn't go out and look [for her] that night, because I don't like going out at night. And especially into a gravel pit where, you know, I didn't know what I was going to find," Sorotski said in an interview with CBC News in February 2018.

Sorotski said she went to the pit around 8 a.m. the next morning. She had Fertuck's dog with her and almost immediately the animal "started to whine and cry because he recognized her truck."

The semi was abandoned, with Fertuck's coat, keys and cellphone still inside.

Sorotski notified the RCMP, and around 11 p.m., the police issued a missing persons bulletin. Police searched the last two places where Fertuck was seen: the farmhouse and the pit.

They found nothing.

Overnight, the weather turned and a light layer of snow covered the semi and the surface of the gravel pit. Sorotski called her son Darren to help search the area. She also called the people who owned the land, the McJannet family.

At the time, John McJannet thought there must be a logical explanation for Fertuck's absence. She could have had a medical emergency, or maybe her truck stopped and she went to look for help. Maybe she fell and injured herself.

It didn't look like a crime scene.

"There was no place where you could see that somebody would have fought," said McJannet. "I mean, there was no paper on the ground, there [were] no articles of clothing. There was no blood or anything around."

Sorotski, who died of cancer in mid-2018, would never learn what happened to her daughter.

Three and a half years later, people in the community still didn't know what became of Sheree Fertuck.

But this past June, despite the absence of a body, the police finally put forth their theory.

Murder.

II.

For urban dwellers in Saskatchewan, Kenaston is just another grouping of houses off the main highway between the province's largest cities, Saskatoon and Regina.

Kenaston, with its population of just under 300 people, is the blizzard capital of Saskatchewan — at least according to a sign near a snowman statue at the end the town's Main Street.

For farmers in the area, it's a hub that helps them avoid trips to the city by providing the essentials: a post office, churches, a school and a gas station that doubles as a grocery store.

Grain elevators tower at the end of the main drag. There's a Chinese restaurant where, two times a day, retired men gather to catch up on the local gossip at a meeting they call "coffee row."

The gravel pit Fertuck worked at is located in the Arm River Valley, and sits off to the side of a skinny stream. During the day, the pit is briefly visible from the highway as the road winds down into the valley; it disappears out of view as drivers ascend the other side.

Eight-metre-high mounds of gravel surround the pit, and it's far enough away from the road that anyone driving by would really have to be looking to make out a person or a vehicle.

The nearest house is up in the distance, on a hill overlooking the pit, near the highway. Byrne Sagen lives there with his wife, but he said they weren't home on the day Fertuck disappeared.

Jeff Sagen, Byrne's cousin and another gravel hauler in the area, owns a pit just north of the one where Fertuck was last seen. Jeff's wife, Tara, noticed that as it was getting dark that day, Fertuck's semi was still down in the pit, with the headlights on. She didn't think much of it. Maybe Fertuck was still working at night. Sometimes Sheree's brother, Darren, did that when he was crushing gravel to get it ready for hauling.

When police came to ask Jeff Sagen if he'd seen anything, he told them he noticed something strange on the day Fertuck went missing: He and a worker heard loud "jaking" in the valley that day.

"You know, when you go to slow down with the semi, they jake — they make that loud noise … it's an engine brake, is what it is," Sagen said. "If somebody was going down into the valley too fast and wanted to slow up, they might hit their jake brakes."

Barkley Prpick, a longtime friend of Fertuck, said that in talking with people in the area, the idea came up that one of Sheree's competitors could have wanted to harm her. But the theory didn't make sense to him.

"Nobody's cranky. She didn't undercut anybody on the bid for the project," said Prpick.

There were other gravel companies operating in the area, and police said they were questioned. But at the time, the RCMP didn't publicly comment about where their investigation was leading.

Fertuck's brother, Darren Sorotski, was also questioned by police. But Juliann Sorotski said he was quickly ruled out as a suspect.

Darren Sorotski did not respond to CBC's requests for an interview.

III.

When Fertuck first disappeared, the RCMP thought she could've accidentally been buried by one of the pit's towering gravel mounds. They asked the local volunteer fire department to help search through the gravel.

"If she was in there, it would have been too late already to save her. But it was more of a recovery situation by then," said Denis Powder, one of the volunteers. "I was worried about if I accidentally dug her up and cut off her arm ... or her leg or something, you know?"

Once Fertuck's death was deemed suspicious, the case was transferred from the local RCMP detachment to the Mounties' Major Crimes Unit. That's when police realized digging through the pit could have destroyed potential evidence.

Const. Ron Degooijer, of Major Crimes, estimated the piles were probably "20 or 25 feet high" in some places.

Cpl. Pascale Lauriault, who became the unit's search co-ordinator after the digging occurred, said she didn't think the evidence that could have been destroyed would have been significant.

"Evidence doesn't show very easily on gravel, so I don't think that it would've made a huge difference had they not touched anything," said Lauriault. Besides, they would have had to dig eventually, she said, "to see if she was there."

Once police were confident Fertuck wasn't accidentally buried beneath the gravel, they brought in cadaver dogs — animals trained to look for bodies — from Alberta to search the pit, as well as Juliann Sorotski's farm.

They used a handheld infrared device to search for a heat signature in the gravel pit. Eventually, an air search was conducted of the pit and the surrounding area. Police lamented the snow was potentially covering up evidence, making it harder to see a fresh grave from above.

In the days that followed, hundreds of people in the region, police and citizens alike, bundled up with toques and mitts to search the vast expanse of frozen fields for any sign of Sheree Fertuck. It was about 25 below as people trudged over the frozen stalks of harvested crops.

Local farmers were told to check their properties and look for footprints, search abandoned farmhouses and watch for tire tracks — anything out of the ordinary.

Searchers also looked for any sign of animals scavenging or birds circling over a single spot.

Winter in Saskatchewan is long. Temperatures start to dip below zero in November and once the deep freeze sets in, it's not likely to thaw until at least March or April.

After the initial search, there wasn't much the police or the community could do. The fields were icy, the lakes were frozen and it was too cold to stay outside for long.

IV.

For the community of Kenaston, Fertuck's absence was surreal, because everyone knew her.

She grew up Sheree Sorotski, an athletic teen and good student who sometimes locked horns with the high school principal, who acknowledged she was strong-willed, opinionated and smart. Sheree was the player you wanted on your basketball team, an intimidating opponent to anyone who faced her.

Barkley Prpick said Sheree sometimes babysat him and his siblings, and would bring Fleetwood Mac, Kiss and country records over to play. As a teenager, she was already running her dad's loader, hauling gravel; Prpick said she taught him how to drive it when he was 15.

Prpick worked for the Sorotskis' gravel-hauling company as a teen, and described Fertuck as a fair but tough businesswoman.

"She was dynamite. She was a really good person when it comes to working with her and being around her," said Prpick. "You just didn't want to cross her… If you happened to do something foolish — like, if you didn't show up to work in the morning — she'd give you shit, just like the old man."

Fertuck danced at cabarets, watched hockey and bid at local charity auctions. Even when she moved to Saskatoon, about a 40-minute drive away, she never really left the town, because she still worked in the area.

People described Fertuck as a strong, independent person — a "lady living in a man's world."

Not everyone was a fan. Some people disliked that Fertuck was sometimes brash, or that she swore like a trucker.

Friends remember her as having a soft heart behind a tough exterior. According to one friend, her favourite song was When Will I Be Loved by Linda Ronstadt.

"She loved karaoke and she loved to sing," said Cory Ouellette. "I asked her one night when we were out on the town … I said, 'You want to sing for our wedding?' And she said she'd love to. And she did a fabulous job, too."

* * *

During those early months of uncertainty and fear, Sorotski was in daily contact with Fertuck's children: Lucas, 22; Lauren, 19; and Lanna, 17.

The RCMP kept investigating over the winter, doing what they could while cold temperatures inhibited the search. On April 11, 2016, as the weather finally started to warm up, the RCMP made an announcement: Fertuck's death was being investigated as a homicide.

For anyone who knew Fertuck, it wasn't entirely surprising; friends and family never thought there was any other explanation for her disappearance. Those who knew Fertuck said she loved her kids too much to simply skip town.

Juliann Sorotski recalled how her daughter would sometimes make cryptic comments that suggested she feared for her own life.

"She told the kids, 'If anything happens to me, you look after my dog,' which they did," said Sorotski. "She would say, 'Mom, if anything happens to me, do this or do that.' She kind of always had it in the back of her mind that she was very uneasy."

People in the area have their theories about what happened: Some think the person who took her must have had a gun. Maybe they tricked her into getting in their vehicle. Maybe there were two people involved.

And they think the person must have known Sheree.

"She just wouldn't willingly go unless there was something massively wrong," said Ouellette. "You know, the fact that her cellphone and everything was just still there. How can that be?"

Police never said whether they had a suspect, or multiple suspects. But in May, 2016, a detail slipped out in a court file that nobody thought would become public.

In an application from the RCMP to access a family law file, Cpl. Jeremy Anderson wrote, "I have reasonable grounds to believe and do believe that: Greg Mitchell Fertuck, born September 25, 1953 at or near Kenaston, Saskatchewan did commit murder on the person of Sheree Fertuck."

Greg Fertuck was Sheree's estranged husband.

In the same court package, Sheree's son, Lucas, wrote in an affidavit that the RCMP suspected his father of killing his mother and he made mention of divorce.

Lucas was applying through court to be appointed as property guardian under The Missing Persons and Presumption of Death Act.

"The RCMP are currently investigating Gregory M. Fertuck, who is her spouse and against whom she has an outstanding divorce, child support and property application, for murdering her," he wrote.

In the affidavit, Lucas said Greg Fertuck had tried to cash in investments he held with Sheree, and that he didn't know how long police would be able to maintain an order that stopped Greg from doing that.

Greg Fertuck denies any involvement in Sheree's disappearance. The rest of the file is closed, so it doesn't reveal anything further about Greg or his relationship with Sheree.

V.

Greg Fertuck and Sheree Sorotski were married in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico in 1991. Her friends think it must have been a low-key affair — many of them weren't there. That didn't completely surprise Sheree's friends; it wasn't her style to have a fancy wedding with a big dress and a bouquet.

One friend, Joni Zdunich, believes Greg and Sheree first met at a wedding at the Manhattan Ballroom, a banquet hall near Saskatoon. Zdunich was there, and said she wasn't impressed with Greg.

"Man, was he ever a jerk. He was drunk and he was just kind of … miserable. Just loud-mouthed and ignorant."

But friends say Sheree seemed happy when she met Greg.

"I remember kind of seeing this overall joy in her," said Ouellette.

By that time, she was working in the family business. She had studied commerce at the University of Saskatchewan after high school, but the pull of her parents' farm was stronger, and she went back to hauling gravel. Greg, meanwhile, worked as a rail conductor.

In the early days, Greg and Sheree went on holidays together — mainly trips to Mexico to escape the Saskatchewan winter. They also went hunting and fishing on camping trips with friends. Greg loved hunting, and he liked guns.

In 1993, Sheree found out she was pregnant with their first child. Lucas Fertuck was born in December of that year. Three years later, in 1996, Lauren was born, followed by Lanna in 1998.

In 2001, the family found a split-level home on a quiet crescent in Saskatoon's west side, and bought the house under Greg's name.

Sheree's mom said there were times when her daughter confided to her that she and Greg were arguing.

"Sheree was a big girl, she could fend for herself. But, you know, there were different instances where she ran out of the house because he was either abusive with her, verbally and/or physically," her mother said.

Sorotski said she once confronted Greg about it, and he denied it. "[He said] 'I wouldn't do that to her, I loved her,'" Sorotski said.

When Sorotski sat down with CBC News prior to her death, she was concerned about speaking on the record about Greg.

"I don't even know if I should have this recorded … I'm kind of careful about what I say," she admitted in the 2018 interview. "Because, I don't know, he could come out here some day and kick the door in, because he does not like me ... I don't like to say too much against him, just for that reason."

* * *

Indeed, there was trouble between the Fertucks.

On Nov. 30, 2010, Greg pleaded guilty to uttering a death threat against Sheree, as well as to possessing a prohibited weapon.

According to the agreed statement of facts, it started with an argument earlier that month, on Nov. 9. Sheree went to the police station in Saskatoon, saying Greg had threatened to kill her.

Earlier that day, she also took his handgun, along with two loaded magazines kept unsecured behind a closet door in the family home. The court record doesn't say why she took the weapons, only that Greg was intoxicated at the time.

He wanted the gun back. When Sheree refused, he told her, "There's another gun, I'm going to get it and put a bullet between your eyes."

When police arrived at the home that day, they found several firearms and ammunition, including 15-round magazines for a 9-mm handgun.

After he was charged, Greg was ordered to have no contact with Sheree or their three children. He was also prohibited from visiting the family home.

On Nov. 23, 2010, the court order was amended to allow Greg to have contact with his children, but he still wasn't allowed to contact Sheree, except by phone or mail "to provide financial support or to discuss finances."

Greg went to counselling as part of a Saskatchewan program called the Domestic Violence Treatment Option. It's a therapeutic program designed to help offenders rehabilitate and reduce the chances of another violent incident.

People who plead guilty and go through the approximately 50-hour counselling program receive a reduced sentence.

After finishing the program, Greg was sentenced on April 12, 2011.

His lawyer, Morris Bodnar, told the judge alcohol was a problem for Fertuck, and that he had started going to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. Bodnar also said Fertuck wanted to get back together with his wife and maintain the family unit.

Fertuck told the judge he was sorry, that he had quit alcohol and joined the family church, and had a letter saying so.

Crown prosecutor Matthew Miazga suggested the court put a five-year ban on Fertuck owning firearms, but the judge dismissed the suggestion. Taking into account Fertuck's participation in the counselling program, the court gave him an absolute discharge.

That meant that although Fertuck pleaded guilty, no conviction was registered and he was not required to abide by any conditions after he was sentenced. "You have been a successful person in the community for quite a long time," the judge said, citing his "35-year career" with Canadian National Railway in "a responsible position."

Fertuck left court with an order to pay a $50 surcharge. The weapons seized by police were not returned to him.

* * *

Some of Sheree's friends said they knew the couple's marriage had problems, but she wasn't one to talk a lot about her private life — until July 2012.

That's when the problems inside the family home became public for the first time, after the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix newspaper published a story about another domestic incident for which Greg was sentenced.

According to the court record, Greg grabbed Sheree by the head and neck and dragged her out of a room during an argument.

Lucas Fertuck, 18 at the time, intervened. When police arrived, Lucas led them to more guns, saying his dad told him the last time the police came, they hadn't gotten them all.

Greg's cousin, Sandra Twardy, said Sheree opened up to her about the fight.

"Sheree never gossiped about him, not really," said Twardy. "When she told me that, I did believe her. And then it was in the paper."

Twardy said Sheree "was worried about the kids and she said, '[Greg] just can't live here, he just can't stay here.'"

In a black canvas bag, police found an Uzi mini-carbine and a pouch containing four high-capacity 25-round Uzi magazines.

There was also a .303 calibre rifle, with no locking device, found leaning against a wall in the garage. And they found a Winchester 22 pump-action rifle.

Greg pleaded guilty to assault against Sheree, possession of a prohibited firearm (the Uzi), unregistered possession of the rifles and magazines, and unsafe storage of the rifles.

During sentencing for the 2011 assault and weapons charges, the Crown argued Greg should spend a year behind bars and get a lifetime ban on owning weapons.

Morris Bodnar, still Greg's lawyer, said the Crown's submission had gone "completely overboard," citing that Fertuck "received a discharge before, went through programming that was required [and] he has no convictions."

Bodnar told the court it was Sheree, not Greg, who brought the Uzi into the house, and defended his client by highlighting some of his challenges.

"In my mind, as well as the probation officer's mind, Mr. Fertuck has an alcohol problem," said Bodnar. The lawyer also emphasized that Fertuck grew up in an "environment" that "could be described as one of an abusive situation. In his childhood, his father, he says he may have been an alcoholic."

In her sentencing decision, Judge Sheila Whelan said that compared to the kinds of assaults she routinely heard about in court, what Fertuck had done was at the "low end." But she noted that Canadian Parliament regarded domestic violence as a very serious matter, and that it was an aggravating factor in this case.

On July 31, 2012, Fertuck received a six-month conditional sentence, meaning he was allowed to serve it in the community, provided he abided by court-ordered conditions.

By this time Greg had started dating a woman named Doris Larocque. They were living together.

Fertuck's probation order prohibited him from drinking alcohol or visiting bars for one year. For the same period of time, he was not allowed to have any contact with Sheree, "directly or indirectly ... except by phone if you have not consumed alcohol or through a member of the Law Society of Saskatchewan."

The Crown did not address where the Uzi came from. Members of Greg's family later backed the explanation that Sheree bought the gun for Greg, and that they used to shoot it together at the gravel pit.

At the sentencing, Greg was banned from owning weapons for 10 years. Again, he left court with a $50 surcharge.

By Jan. 13, 2013, Greg had breached those conditions. According to a Saskatoon Police document, a taxi driver brought him to the police station for being too intoxicated to pay his fare. Greg spent 16 days behind bars, which the court deemed to be enough not to warrant further action.

His conditional sentence was over at the end of January anyway.

VI.

Saskatchewan has the highest rate of police-reported interpersonal and domestic violence of any province. Between 2005 and 2014, there were 48 domestic homicides in the province.

Domestic Violence Courts, which offer therapeutic sentences for those who take responsibility for their actions or plead guilty, operate in Regina, Saskatoon and the Battlefords. A 2011 study focused solely on domestic violence in Saskatoon found that the number of people who ended up back in court was lower if they went through the therapy program.

Even so, 20 per cent of people who completed the program went on to reoffend.

Crystal Giesbrecht, a domestic violence counsellor who interviewed men who had been violent with their partners for her master's thesis in social work at the University of Regina, believes offering treatment as part of the justice system is "crucial" to reducing the rate of reoffending.

However, she wants more education for people working with domestic violence in the justice system.

"One thing that I personally would like to see is more consistency to ensure that when threats have been uttered against that victim ... that is taken seriously," said Giesbrecht, who is director of research and communications at the Provincial Association of Transition Houses Of Saskatchewan. "I know sometimes it is and sometimes it isn't."

One way to improve that response, she said, is "more education on intimate-partner violence and specifically intimate-partner violence risk assessment, so that the professionals have a clear understanding of some of these risk factors. And not only that they are predictive of risk, but then what do you do in terms of management."

In Saskatchewan, two standardized forms are used to assess a person's risk of reoffending: The Saskatchewan Primary Risk Assessment and Ontario Domestic Abuse Risk Assessment. After the death threat in 2010, Domestic Violence Court workers concluded Greg Fertuck was a low risk to reoffend.

Giesbrecht said the justice system should be looking at domestic violence cases as a whole. She said it is "absolutely necessary" that past history with domestic violence be taken into consideration during sentencing, and to inform risk management and treatment plans.

Although the absolute discharge left Greg with a clean criminal record, it did not wipe his conviction from the court record. It's not clear how the death threat conviction factored into the judge's decision on how to sentence Greg for the 2011 assault. Former judge Sheila Whelan, who presided over the case, declined to be interviewed by CBC News.

VII.

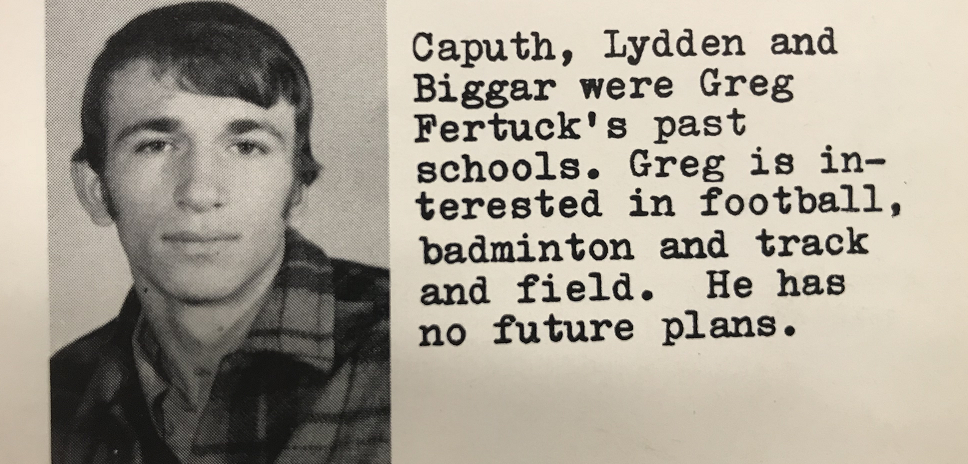

Greg Fertuck grew up on a farm near Biggar, a small town about an hour's drive west of Saskatoon. Its slogan: "New York is Big, but this is Biggar."

Sandra Twardy used to visit the Fertucks at their farm, and said it was always a great time, full of "teasing and laughing." But she also said that Greg "had it rough" growing up.

He graduated from Biggar Composite high school in 1971; the blurb next to his yearbook photo says 'he has no future plans." He soon started working at Canadian National Railway.

In 1974, he married Sandra Lee Link, and around this time, they had a child, Michael. Greg and Sandra were divorced within five years.

Both Sandra and Michael declined to be interviewed.

It's not clear if there was a woman in Greg's life between his divorce from Sandra and meeting Sheree.

Twardy said she wasn't in regular contact with Greg until after Sheree's disappearance. But she remembered their first conversation after Sheree went missing.

"He went on a rampage about [Sheree], saying names or whatever. I don't want to repeat that. But then I said to him, 'Greg, there was good times,' and he was quiet, and then he said, 'Yes, there was.'

"After that, when I spoke to Greg [and] Sheree's name came up, he'd always be on the negative. And I'd say, 'I don't want to talk about it, Greg, I don't want to hear that.'"

Twardy said she never saw a violent side to her cousin. She said he looked after the children when they were younger and Sheree was working, and he did some of the household chores, like gardening and laundry.

After Sheree disappeared, Twardy said Greg started calling her for long chats; she thinks most of the time, he had been drinking. He rambled, she said, jumping from talking about his childhood to the present moment — back and forth. In some of those calls, Twardy said he spoke of "getting rid of people."

"In a drunken stupor, he would say that would be easy to do or something," she said. "His thoughts were so irrational, out there — one minute, the farm, one minute, the work. It was off in all directions. I'd get off the phone sometimes and I didn't know what he was saying."

Twardy said she started avoiding his calls, and hasn't been in contact with Greg since spring of 2018.

Twardy claims she's now fearful of Greg — a feeling she thinks has grown out of both the news reporting about him and the anger he displayed in those phone calls.

"There's two different Gregs. You could have a conversation with Greg when he wasn't drinking," she said. "[But] when he drank, you couldn't have a conversation with Greg."

Twardy is among a number of people who spoke to CBC about Greg's drinking.

Barkley Prpick remembers him drinking at his bar in Bladworth, a 15-minute drive southeast of Kenaston. More than once, Prpick said he had to cut Greg off and ask him to leave because he was "scaring the customers."

"When he wasn't drinking, he was pretty nice, quiet. But when he was drinking, he could be a little sketchy, I'll call it," Prpick said. "He had no problem calling the waitress a bitch because she didn't bring him another drink."

Prpick said that money always seemed to be a problem in the Fertuck household.

He said he never heard him say anything that suggested he might want to harm her.

VIII.

On June 25, 2019, three and half years after Sheree went missing, the RCMP announced Greg Fertuck had been charged with first-degree murder and causing indignity to human remains.

It was a surprising move, given that Sheree's body still hasn't been found.

"Although it's unusual, there have been successful prosecutions before without a body being found," said Supt. Derek Williams, adding that the search for Sheree's remains continues.

Police said they arrested Greg on the outskirts of Saskatoon at about 6:30 p.m. that night. At the same time, police searched a rural area near the gravel pit. Carloads of officers dispersed across the rolling green farmland.

They wrapped up the search after four days, without any sign of Sheree.

Back in Saskatoon, Greg Fertuck appeared in court wearing a khaki shirt, his hands folded in front of him. The judge set a date for his next court appearance.

On hand for that first court appearance were Fertuck's mother, Elma, and brother, Reg. They told CBC News afterward that Greg is innocent, and claimed that the RCMP used undercover police in the investigation that led to his arrest.

"They were at his place yet in the fall. They'd come over, but he didn't know they were undercover cops. They'd come and drink, have coffee, drink, lunch at his house. This kept going on for … a long time," said Elma Fertuck, her voice shaking.

Reg Fertuck said he didn't believe any police evidence would prove his brother was responsible for Sheree's death. "We come from a family that talks foolish, and you know what guys are like when they're drinking in the bar: 'Oh, I'll kill you,' or say this or that. You know, guys talk stupid and silly. Half my friends talk like that."

He added: "Whatever they heard on tape or whatever they got on tape ... it's all bogus."

Elma and Reg Fertuck both said Greg is not a violent person, and that they didn't know anything about Fertuck's prior convictions, including the assault.

But they did bring up the Uzi.

"He wouldn't tell the police that she bought him the machine gun or what guy she bought it from," said Reg. "He didn't want to squeal on her because that was his wife and he loved her and he didn't want her to go to jail."

Greg started taking antidepressants after Sheree went missing, said Reg Fertuck, and that he "almost lost it" because his wife was gone.

* * *

A former friend and colleague offers a different perspective.

Ron Stachowich worked with Greg at CN. In earlier days, the two went hunting and fishing together with their wives, but the outings dwindled over time because Ron's wife, Janis, didn't like Sheree.

Greg moved in with Stachowich at the end of 2011 — around the time of the assault. It was a short stay.

Police interviewed Stachowich not long after Sheree's disappearance. When CBC contacted him, he said there was information about Greg that he did not share with police. He said he was nervous and didn't know how much he should say.

"I wanted to give the police a chance to possibly find a body and find out for sure what's actually going on," said Stachowich.

Greg was drinking heavily at the time they were living together, he said, which was part of the reason Stachowich kicked him out within four months.

Stachowich said that Fertuck "cursed [Sheree] every day," and there was something in particular that Fertuck confided to him in a "drunken scenario."

"Situations where he sat on the couch here, and told me ... 'I'm going to get rid of her and bury her in the north 40' — wherever that might be, I don't know. And the mother-in-law was going to go there with her," Stachowich recalled.

Asked what he thought about Greg's comments, Stachowich replied, "I don't know if anything would surprise me that Greg really does. I don't believe a lot of the stuff that he even told me."

Stachowich said he believes Greg was responsible for Sheree's disappearance. Although he shared this information with CBC in November 2018, he initially refused to allow it to be reported.

At the time, he said he felt that if the comments got out, "I don't think I'd value my life too much. Because if he did do it, the second one ain't going to hurt him at all."

After Fertuck was arrested, Stachowich granted CBC permission to use the interview.

Stachowich admitted he wasn't a "fan" of Sheree. He remembers her being a mean person, refusing to share a fridge while camping and telling Greg he could not use their vehicles for hunting.

His impression was that Greg and Sheree did not get along well. He remembered Greg complaining about Sheree withholding money that he felt was rightfully his, calling her a "fucking bitch."

But Stachowich said he never saw any signs of violence between the two.

After Sheree disappeared, the family's gravel crushing and hauling business started to wind down. In 2019, the Sorotski farm was listed for sale.

Missing persons posters still hang around the town of Kenaston.

"I think, as a community, we are still looking for answers," Dee Guy, a close friend of Juliann Sorotski, said in November 2018. "Sometimes it takes a long time, in this world, to find out what really are the answers. And we may never know."

Greg is scheduled to next appear in court on July 22. At the time of this story, he had not entered a plea.

IX.

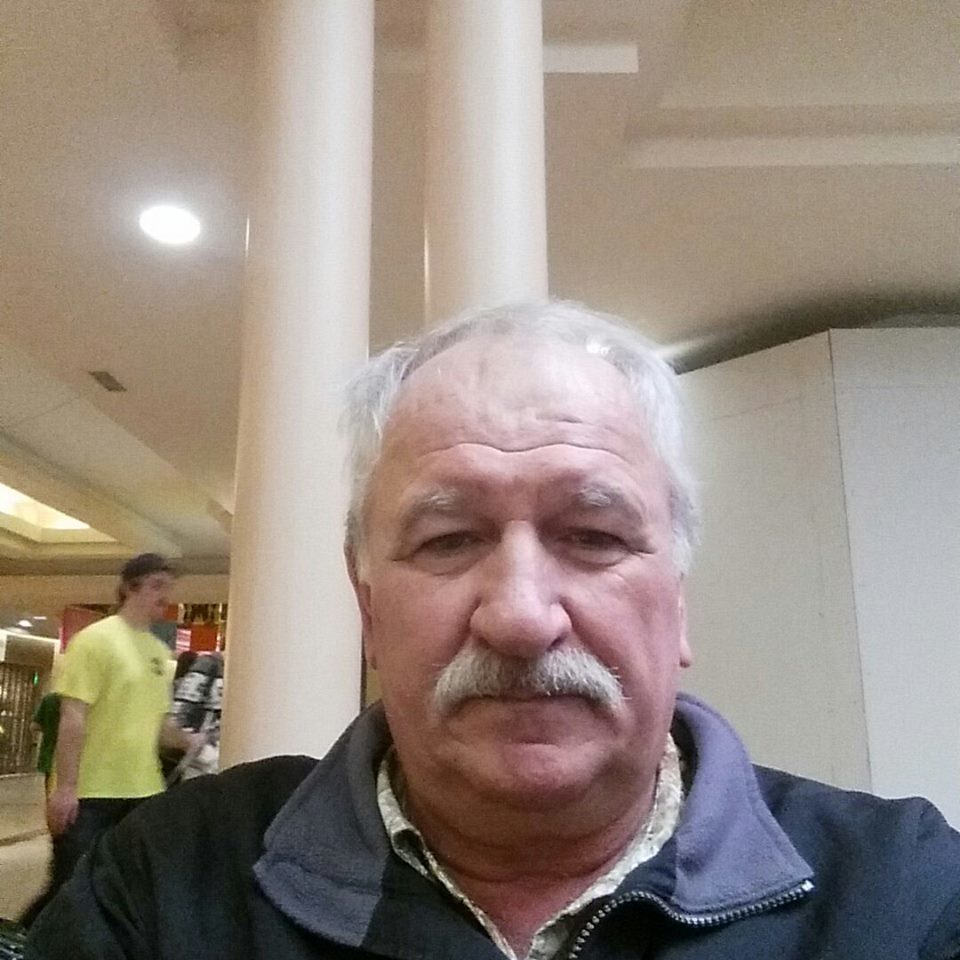

With that appearance just days away, Greg Fertuck agreed to an interview with CBC at the Saskatoon Correctional Centre.

The interview took place in a boardroom with motivational posters on the wall. Outside, inmates in orange jumpsuits are being ordered around by guards. Heavy metal doors separate the cool corridors.

Greg Fertuck is wearing handcuffs and an orange T-shirt; he has scruffy grey hair on his head and face.

Right away, he says he is innocent.

Fertuck is polite, but gruff, and uses his words sparingly during the 40-minute interview.

But within the first minute, he explains he has a memory issue because of a head injury from a fall in December 2018. He slipped and hit his head on his way to a restaurant, he said.

"When I fell, I guess I had a ruptured blood vessel in my brain. It started bleeding and that's partially the cause of my amnesia or whatever you want to call it," said Fertuck. "I was in the hospital for over two months so I lost a bit of my memory."

Fertuck said he thinks he was at home in Saskatoon on Dec. 7, 2015, the day Sheree disappeared, but later said he does not remember if he was in the area of the gravel pit at the time.

He also said he doesn't remember meeting his wife that day.

Greg denies killing Sheree. He said RCMP used a "Mr. Big" operation in the investigation that led to his arrest. Mr. Big sting operations involve police posing as criminals in an attempt to obtain a confession from a suspect.

Mr. Big stings are controversial in Canada and have been criticized for inducing false confessions.

Greg said he doesn't remember meeting the two undercover officers because they befriended him before his accident.

They came to visit him in the hospital, he said, showing him photos of them all together to prove they were friends and that they had been working together.

After seeing the photos, Greg said he took their word for it.

The men worked together picking up cars in Hague, Sask., driving them back to a lot in Saskatoon. They would get dinner at restaurants like The Keg and Manos after work, and Greg said they were "sort of friends."

Greg said he told the undercover officers he "got rid of" Sheree, and that he "threw her in the bush." But he said he fabricated the story because he was afraid the men, who he thought were mobsters, were going to kill him.

"I kind of thought they were criminals, because this one guy [said he] killed his girlfriend, and I know he had blood all over him, scratches on his face," said Greg. "And this guy from Vancouver … come in and got rid of everything, sort of the cleanup guy."

He eventually met the top dog, who Greg described as looking like a crime boss in the movies.

Greg said he told them he killed Sheree when he found himself in a situation with "the cleanup guy" and the crime boss.

"When I called into the hotel room [in Saskatoon], he said I cost him a bunch of money because some cops were looking into me. I didn't know what he was talking about..." he said.

"And then I saw ... the cleanup guy, so that's when ... I got worried for my safety. I was being intimidated anyway."

Greg said they got in a car and went to find Sheree's body. "We drove around a country road, went through some bushes, that's about it," he said.

Again, he reiterated his story about killing Sheree was made up.

Greg said he was "shocked" when police arrested him.

CBC asked Greg about the 2010 death threat and the 2011 assault against Sheree, and he said that although he didn't remember much, he knew he never assaulted Sheree.

Greg said he does not remember going to court, or who his lawyer was at the time, because of the head injury. Morris Bodnar is still representing him at the time of this story.

But Greg said he remembered his role in one of the two incidents.

"I remember one time she come at me and I just pushed her back. She was going to punch me with her fists," he said.

"I never threatened her. I did push her back. I thought it was just self-defence but I don't know. She was very, I don't know, out to get me, I guess."

Greg said he did not remember having many arguments with Sheree, or any disagreement over money.

He laughed when CBC asked about Stachowich's claim that Greg told him he was going to get rid of Sheree and her mom by burying them in the "north 40."

"Well, I don't remember saying something that stupid. I can't say I would say something, because that's really far out. But they said I was drinking. I don't know what I was like when I was drinking," said Greg. "After I got out of hospital, I quit drinking."

CBC also asked Greg to address Twardy's claim he talked about getting rid of people and said "it would be easy to do."

"I've never gotten rid of anybody and I don't think I would talk like that either," he replied.

Greg said he does not remember why the divorce was filed, or whether he was angry at Sheree about the house or financial disputes, again, because of the head injury.

CBC put it to Greg that people may not believe he has memory loss, as it could be considered convenient in the circumstances.

He said he doesn't care if people believe him.

Throughout the interview, he repeated that he loved Sheree and would never hurt her.

Greg also told CBC he plans to plead not guilty at his next court appearance.

In the past year that CBC has spent researching and interviewing for this story, Sheree's siblings and children either declined to comment or did not return calls.

On July 3, after Greg was charged, Sheree's sister, Corelie, who goes by Teaka, sent a brief statement in a text message.

"All that I wish to say is that our family is happy/pleased that an arrest has been made and that charges have been laid," she said.

"I do not wish to comment on Greg or anything else about Sheree's case at this time."