The package arrives by mail, delivered by Canada Post. The small manila envelope looks the same as countless other parcels the postal service delivers each day. But its contents are criminal.

A pouch stuffed inside the cushioned envelope conceals 250 milligrams of methamphetamine.

A Calgary teenager ordered the stimulant from what he calls the Amazon of drugs, an online market accessible only in the deepest corridors of the internet known as the dark web. Heroin, carfentanil and LSD have also steadily arrived in his community mailbox for the past two years, sometimes at a rate of three parcels a week.

"There's no dealer in Calgary that can match the huge selection that's available on the dark net," says Liam, whose real name isn't being disclosed by CBC News because he fears potential criminal and other repercussions if he goes public.

Drug trade moves from street to web

There are many others like Liam.

They're shopping for drugs on the so-called dark net, accessible not through traditional search engines but by way of special browsers and software that conceal IP addresses and make users harder to trace.

These drug markets are clandestine dispensaries of illicit and dangerous substances that are sold in exchange for cryptocurrencies, such as bitcoin. For police, they pose a challenging front in the fight against the opioid crisis.

The Public Health Agency of Canada predicts the number of opioid-related overdose deaths for 2017 will surpass 4,000 once the figures are available from all provinces and territories. Fewer than 3,000 such deaths were reported a year earlier.

According to the RCMP's national headquarters and municipal police forces in cities such as Calgary, there are growing indications that the drug trade is increasingly moving to the dark web.

There are signs that Canada has played a role in this shift. The country was at one point home to among the highest number of dealers globally in one dark web market, called AlphaBay, which was ultimately shuttered by police.

But like a never-ending game of whack-a-mole, law enforcement agencies around the world employ new tactics to stamp out anonymous markets, only to see new ones pop up.

• Dark web's largest illegal marketplace, founded by Canadian, shut down by U.S.

• Police ran 2nd dark web marketplace as sting to spot drug deals

Beginning with Silk Road, the first large-scale dark web drug market, in 2011, traffickers and users have been flocking to these sites in part because they offer a degree of anonymity not available on the street. Specialized software, such as the commonly used Tor, routes user data through myriad servers and nodes around the world, disguising IP addresses — and by extension, identities — and making it difficult for law enforcement to track.

Communication between buyers and sellers is generally scrambled with the help of encryption tools. And cryptocurrencies add another layer of protection for those seeking to duck police suspicion.

In Calgary, police say it's difficult to pinpoint how many drug users are flocking to the dark net — and how much they're buying — because the markets change constantly.

'I'd probably rather overdose'

Liam knows what he's doing is dangerous, but he is addicted to drugs and hides his dependency from family and many of his friends. He's so worried that people will discover his double life that he risks overdosing alone.

• Calgary's fentanyl crisis: A close look at the numbers

• 'An absolute crisis': 42 recent overdose calls near Lethbridge linked to toxic batch of drugs

"I just don't want people to see how bad it is," he says. "If [there is a risk] my family finds out about my addiction, yeah, I'd probably rather overdose….

"It would be much, much smarter for me to have someone with me when I'm using, but it's just not something I can really do."

Liam gets his fix from a site called Dream Market, a one-stop shop for drugs.

With roughly 100,000 listings, Dream Market is believed to be the world's largest market on the dark web and the biggest dark net shopping centre for drugs. A little more than half of the listings are for substances that are illicit, unregulated or diverted from legitimate sources.

Dream boasts almost the same number of listings for other products, including items that purport to be designer clothes, counterfeit money and stolen online banking information.

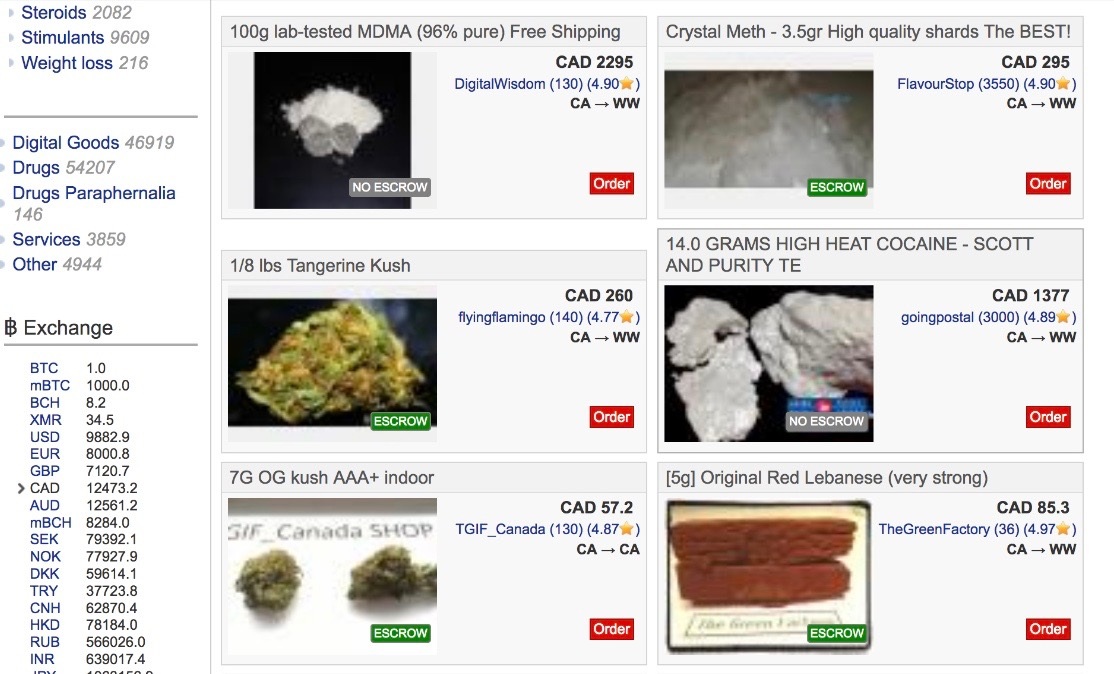

A screenshot of Dream Market, below, shows drugs on offer, including crystal meth, cocaine, hash and MDMA.

Liam buys only from Canadian drug vendors, fearing that importing heroin and meth across the border would put him at risk of investigation by the Canada Border Services Agency. The CBSA has the authority to open and inspect any package entering the country. For domestic mail, however, police must obtain a search warrant or have reasonable grounds to open packages.

In a recent scan of the site, Dream featured roughly 1,000 listings for drugs that ship within Canada, ranging from opium, morphine and fentanyl to ecstasy, ketamine and date-rape drugs.

'They don't need to go to a back alley'

Dream Market and other sites like it are likely helping fuel the deadly fentanyl crisis that has rippled across the country, says Sgt. Mike Lalande of the Calgary Police Service, who investigates cybercrime.

"[Given that] the dark web is anonymous, it allows for a very easy vehicle in order for people to buy drugs," Lalande says.

"They don't need to go to a back alley or a street corner and meet somebody they've never met before, which could potentially put them in harm's way. They can sit at their computer or their smartphone, and they can purchase the drug of their choice and have it delivered to their home….

"It opens [fentanyl] up to a market that probably wasn't there before."

The dark web isn't always used for nefarious purposes, however.

Whistleblowers in government or industry who don't want to be identified can use it to flag journalists to practices they see as immoral or illegal. People living in authoritarian regimes may use it to avoid detection while some access it to avoid having their internet use tracked.

But the dark web also offers drug traffickers cover from police surveillance.

Popularity is growing

Investigators in Calgary say police crackdowns haven't been enough to suppress the growing appeal of dark web markets.

Lalande says media attention that follows dark net busts appears to fuel public interest and likely drives up traffic on the remaining sites.

"The drug trade is moving to the digital space, online, because of its anonymity and its ease of use," Lalande says.

"There's a shift from the old way of the drug trade to more of a modern, technological and digital era of selling drugs."

• How hidden code helps cops identify drug dealers and child predators online

Cybercrime investigators in Calgary, who, Lalande says, are "always working dark web files," face many obstacles. The nature of the dark net forces even municipal police officers to work globally to trace shipments and financial transactions.

"We're targeting the vendor … who is selling uncontrolled and lethal substances to people on the dark web," Lalande says.

He says police are breaking new ground in the way they conduct investigations but would not provide details.

"The courts haven't seen much of it here in Canada. They're fairly new kinds of investigations that police are just sort of understanding," Lalande says.

‘Countless hours of covert surveillance’

Police regularly troll the dark web in pursuit of drug dealers.

Lalande says this work has led to arrests, such as that of a 39-year-old Calgary man who faces a dozen drug trafficking charges, among other offences. His trial is set to begin in November.

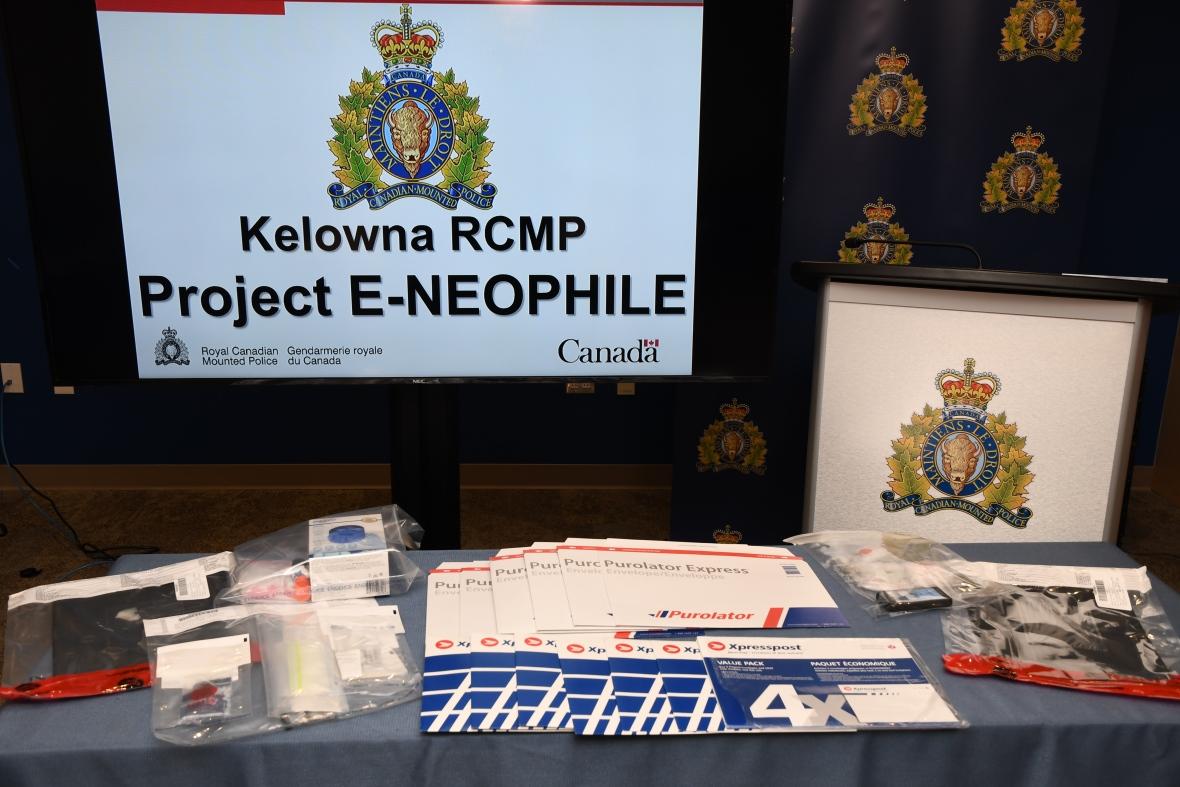

In another case, RCMP in British Columbia declared last fall they had disrupted what may be "one of the most sophisticated fentanyl/carfentanil trafficking and exportation enterprises" they had seen in Canada after arresting two people accused of selling drugs on the dark web.

Investigators posed as buyers and conducted "countless hours of covert surveillance." The probe led to the seizure of up to 25 packages suspected of containing fentanyl or carfentanil, destined for Canadian, American, European and Australian cities.

• Alleged B.C. trafficking ring used dark web to sell fentanyl globally

Working with American and Australian authorities, Canada Post, CBSA and Canadian municipal police forces, including Calgary officers, the RCMP obtained search warrants for a Kelowna, B.C., home and business, arresting two suspects.

Five months after announcing the bust, Mounties say they are continuing to investigate the alleged trafficking ring, though they haven't laid any charges.

The RCMP say they have a national investigative strategy to combat the mail order drug trade in partnership with Canada Post, Health Canada, CBSA and other law enforcement agencies. In a statement, the RCMP said it's attempting to "identify shipping and manufacturing trends, international exporters, domestic distributors, clandestine labs and criminal networks in order to understand the fentanyl situation."

Drugs arrive by mail, 'very discreetly'

Liam stumbled onto the dark net a couple of years ago when browsing the open web. There, he found step-by-step instructions on how to access the deepest recesses of the internet.

The teenager had been using research chemicals — substances that often mimic the effects of illicit drugs but are not federally controlled — but he was looking for a broader variety than what he was getting from vendors on the internet. He was also worried that he was taking chemicals that weren't well researched, with unknown side effects.

• 'Research chemicals' making their way into illicit drug markets, police say

Liam says he was drawn to the dark net in part because of the wide selection and the anonymity. "No one can see that I'm using drugs. It comes directly to me, very discreetly."

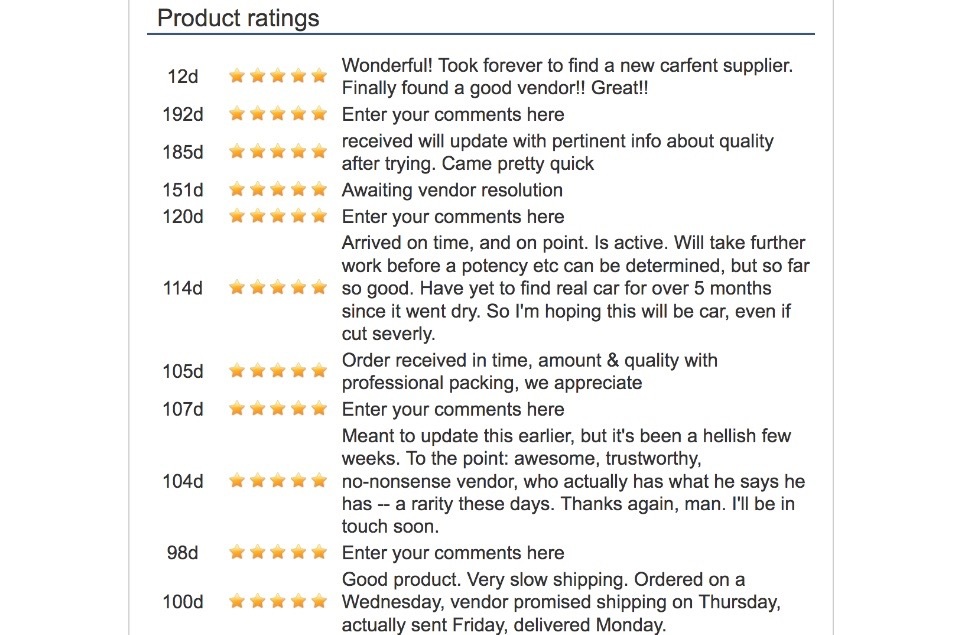

He was equally compelled by the system of vendor and product reviews. Similar to legal online retailers, dark net drug listings feature dozens of reviews, assessing the products for quality, purity and shipping times. Vendors are also critiqued, and many of them have myriad reviews.

A screenshot from Dream Market, below, shows product reviews for 100 mg of carfentanil.

"Wonderful!" raves a five-star review on Dream Market of 100 milligrams of carfentanil available in Canada. "Took forever to find a new carfent supplier. Finally found a good vendor!! Great!!!"

Other reviews referencing the same listing aren't as favourable: "Vendor is never honest about when he will or has shipped out order — very annoying," reads a four-star review. "This last order he gave extra product with the expectation I would just ignore that nothing was shipped when promised or in a timely fashion. Product (G2 carfent) is good quality."

One hundred milligrams of carfentanil, a synthetic opioid more potent than fentanyl used to sedate large animals, could be enough to kill dozens of people, according to Dr. David Juurlink, a medical toxicologist at the Ontario Poison Centre.

Almost 160 Albertans died from carfentanil overdoses last year — half of them in the Calgary area — up from 30 the year before, and the death toll continues to rise.

Dark net purchases a 'calculated risk,' teen says

Liam says he takes a "calculated risk" when he buys drugs on the dark web.

As a "fairly regular customer," he knows the track record of certain vendors.

When a new seller comes along, he'll look at reviews online, both on the dark and open web.

"If you're buying a TV or you're buying a video game … you can check reviews for that item," he says. "You can go through the vendor's page and check all of his or her reviews as well….

"There is certainly a risk to it, at the end of the day. It's just a risk that I've decided to take."

Some researchers who study the dark web have found the quality of drugs available on these hidden websites is superior to that of drugs sold on the street. One theory of why that might be is that the online review system holds dealers accountable, says Rasmus Munksgaard, a Montreal researcher.

One study, published by the International Journal of Drug Policy, scrutinized lab results of more than 200 samples of drugs that were purchased on so-called cryptomarkets and collected by a Spanish NGO from 2014 to 2015. The study found more than 90 per cent of the samples contained the drugs they were sold as, and that most samples were of high purity.

Still, the study's authors cautioned they could not confirm whether their results would closely mirror what users would typically find on dark web markets.

"In any illicit markets, you're going to have some quality uncertainty and uncertainty about what it is you're consuming," says Munksgaard, who wasn't involved with the drug-testing study.

"But we do have a growing body of literature which suggests that people who use cryptomarkets generally consume substances that are of better quality, and they're subject to less drug market violence," says Munksgaard, who is studying trust among vendors and buyers on the dark web for his PhD at the University of Montreal.

'This product could potentially kill you'

Police don't buy the idea that drugs are safer online.

Lalande says while a string of negative reviews may "weed out one bad vendor, another will take its place."

Acting Staff Sgt. Jeremy Wittman, who leads the Calgary Police Service's cyber-forensic unit, says drugs for sale on the dark web are potentially lethal.

"To me, that's very different than buying books or other things from people on a used market, where the risk is you don't get that product, versus this product could potentially kill you."

Dark net markets have proliferated since Silk Road

The first major anonymous online market, Silk Road, emerged seven years ago and quickly gained the attention of media, government authorities and law enforcement, according to a research paper published last month by the International Journal of Drug Policy.

Silk Road offered drugs, porn and fake IDs and driver's licenses for sale. It was shut down by the FBI in 2013, but the concept had already caught on.

Many more sites took its place.

As of last fall, there were nearly two dozen dark net drug markets of various sizes, according to a research paper by Meropi Tzanetakis of the University of Oslo and the University of Vienna.

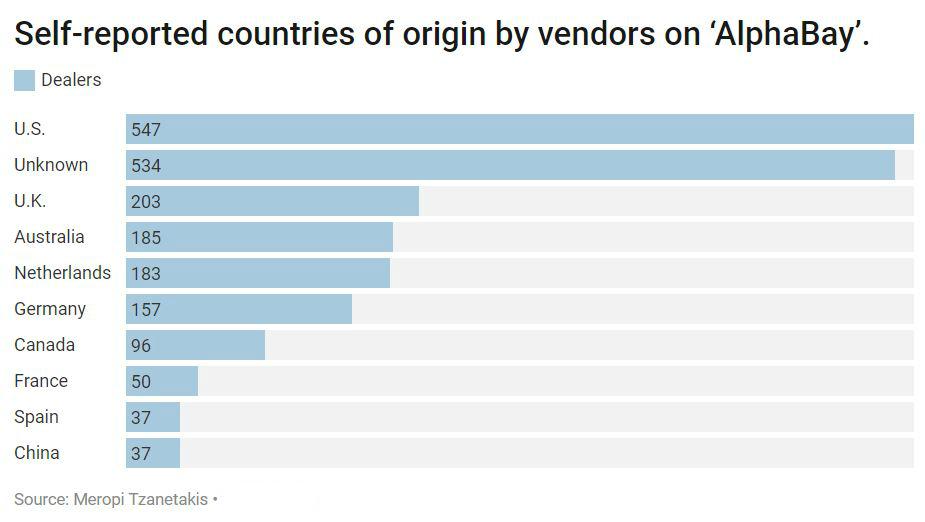

AlphaBay, which was the largest dark net market before it was shut down by law enforcement agencies around the world last year, accounted for $94 million US in drug sales from September 2015 to August 2016, Tzanetakis's paper says.

Canada was 6th largest source of dealers on AlphaBay

AlphaBay, which police allege was founded by a Canadian, was home to nearly 2,200 vendors with about 12,000 drug listings, according to Tzanetakis, who used a web-scraping tool to extract data from the site.

The researcher found about 95 sellers, or four per cent, indicated they shipped from Canada during the 12-month period. Canada had the sixth-highest proportion of dealers on the site (among those who specified a location), outpacing France, Spain and China.

The United States topped the list, with a quarter of vendors shipping from south of the border, followed by the United Kingdom, at nine per cent.

Another 24 per cent of sellers didn't indicate the country they were shipping from.

The most popular products for sale were stimulants, such as cocaine and crystal meth, which accounted for 20 per cent of sales.

Cannabis was second, with 18 per cent of the market, followed by opioids, including fentanyl, heroin and oxycodone, which together accounted for nearly 13 per cent of sales.

Users are largely younger men

In her paper, Tzanetakis said that other studies have suggested that most users of dark net markets are men in their early to mid-20s who either work or are studying at the post-secondary level. They're largely occasional or recreational drug users, though some have potentially problematic addictions, she wrote.

Liam says he takes drugs to medicate the effects of childhood trauma (he was beaten by one of his parents, he says) but that he's seeking help. He recently started meeting with addictions specialists. He says he's motivated to stop using drugs because he's enrolled in university this fall and doesn't want drugs to get in the way of his career ambitions.

"Addiction is certainly something that really does make you a shell of your former self. It's not something that you can just fix overnight or even fix in a week or a month," he says. "Every day that you delay getting treatment or getting better, you are just postponing that.

"But at the end of the day, there's really two options — either I get better or I die from drug use."

Reid Southwick is a reporter with CBC Calgary. If you have a good story idea or tip, you can reach him by email at reid.southwick@cbc.ca or on Twitter @ReidSouthwick.