April 3, 2021

It was 1944, and 18-year-old Eileen Penney of Humbermouth — a tight-knit community near Corner Brook, in western Newfoundland — had been waiting for her boyfriend to return home from the Navy. She wanted an adventure, too.

“I think she was anxious to do something other than stay at home and help her mother,” said Penney’s daughter, Terry Gullage.

In Nicholsville, near Deer Lake, in 1947, teenager Daisy Nichols was itching to have her own space.

"She was the oldest of 12,” said her daughter, Gail Hammond. “I believe she just wanted an opportunity to find work, and maybe to get away from being the oldest, and looking after everyone else.”

Penney and Nichols were recruited by Dominion Woolens and Worsteds Ltd., a huge textile mill in the town of Hespeler, now the city of Cambridge, Ont.

The two were among hundreds of young women from western and central Newfoundland who travelled up to the mill in southwestern Ontario to work during the 1940s. However, their stories —about work, women and the vanguard of an industrial migration that would profoundly affect Newfoundland and Labrador — have largely been forgotten … until recently.

Writer, actor and playwright Bernadine Stapleton became interested in their story after hearing about them a few years back from Cambridge playwright Nicole Smith, at the Womens’ Work Festival in St. John’s.

“I couldn’t believe it,” said Stapleton. “I’ve done a lot of writing, a lot of research, a lot of reading. As a female writer performer, this never crossed my radar.”

“It was more than just a demographic shift. It was cultural, it was financial, it was feminist.”

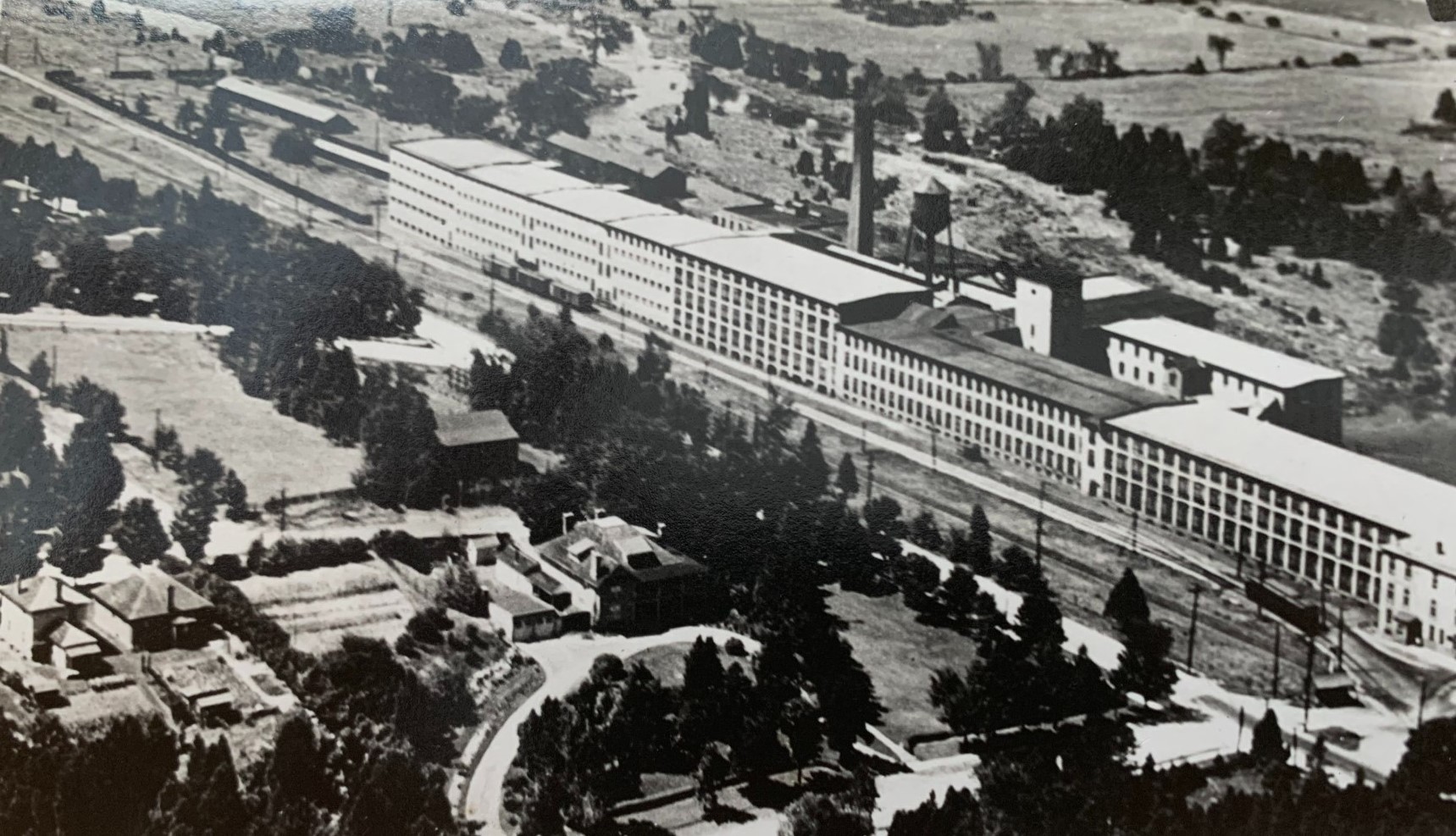

Largest textile mill in the Commonwealth

In 1940, Dominion Woolens and Worsteds of Hespeler, Ont., was the largest textile factory in the British Commonwealth. It was a huge complex of buildings, covering about six hectares, or 15 acres, of land.

It operated 24 hours a day, six days a week — rolling out fabric for clothing, household items and Canadian military uniforms.

Thousands of people from the surrounding area worked there. But the mill was facing a dramatic labour shortage, as more young Canadian men signed up for military service.

The Canadian government and mill bosses decided the solution was to recruit young, unmarried women, assuming they would not have family obligations to prevent them from working long hours.

Several recruiters went to Newfoundland, where they would go into small communities, rent a hall, and show a glamorous recruitment reel.

“Food played a lot into the recruitment at the time,” said Stapleton.

“And socializing was a really big deal as well. “We saw a lot of pictures that, like they're riding their bikes, looking very perky. They had a baseball team. They had a choir.”

Penney had to get a letter of referral from her Anglican minister to let her go. Nichols just forged her own paperwork.

Keeping the workers happy

After days, even weeks of train and ferry travel, the Newfoundland recruits arrived in Hespeler.

The work at the mill was physically demanding. The hours were long, and the factory floor was very hot, loud and dusty. Turnover among workers was high.

But Valerie Spring, a Cambridge historian, said that the company made a special effort to convince the Newfoundland girls from so far away to stay.

“The mill had a recreation co-ordinator, they had a well-known women’s softball team, there were dances organized, excursions organized,” Spring said.

“There was an orchestra, choir, sports teams, dances, picnics. The mill really tried to keep them entertained,” Spring said.

“It was a smart move economically because if you have happy workers, they will continue to work there.”

Eileen Penney and Daisy Nichols loved life in the mill girls’ residences.

“For mom it was something different than having to cook and clean at home,” said Penney’s daughter, Gullage.

“She made a lot of friends,” said Hammond. “[Mom] played hockey — she was on the Dominion Woolens baseball team.”

The young women from Newfoundland also revelled in their freedom. They were earning their own money, and had control over their free time.

But between the long, hard work hours, and the whirlwind social life of their spare time, most of the mill girls only lasted at Dominion Woolens and Worsteds for a year or two.

Where did they go?

After that, it’s unclear where most of the young Newfoundland women went. Some came home: Eileen Penney moved back to Newfoundland, and married her sweetheart, who had returned home from the Navy. Many of them, though, including Daisy Nichols, married men from the Hespeler area and built their lives in southwestern Ontario.

Hammond and Gullage said their mothers just got on with raising their families and didn’t talk much about their pasts.

Spring was one of the few researchers who actually asked some of the women about their work at Dominion Woolens and Worsteds.

LISTEN | Hear Heather Barrett's full CBC Radio documentary The Mill Girls:

Spring said when she was interviewing the former mill girls for her graduate history thesis in the 1980s, the women were so shy about talking about their younger lives that they made her promise that the tapes of their interviews would not be available to the public for 25 years.

“They were incredibly modest, like, ‘why would anyone be interested in what I did?’” said Stapleton.

“I think nobody ever sat them down as a group and said ‘Did you know what you did?’”

A telling detail is found in an undated photo from the 1940s. The group photo — which is displayed at the top of this feature — was taken on the factory floor, and shows 11 young female workers, smiling and arm in arm, with two of their male supervisors standing in the back. The only names documented with that photo were of the men.

An influence felt decades later

It was because of the mill girls, said Stapleton, that out-of-work miners from Bell Island in the 1960s heard about factory jobs in Cambridge. That started a massive wave of Newfoundland migration to the industrial belt of southwestern Ontario.

By the 1970s, one out of every four residents of Cambridge was from Newfoundland.

Eileen Penney Hiscock passed away in 1998, and Daisy Nichols Westwood, one of the few remaining Mill GIrls, is in her nineties.

There were hundreds of young women like them. Most of the accounts of these women who set out in the world in the 1940s have been lost to time.

As a historian, Spring said she is glad that there is renewed interest in the Mill Girls, but she is worried that womens’ work is still not taken seriously enough by society at large.

Smith and Stapleton are continuing to research, write and workshop their play, called Girls From Away, and they are committed to spreading the word about these women.

“We have this vision of opening our play at the Grand Falls-Windsor Gordon Pinsent Centre for the Arts and just having these huge pictures of these girls from away all over the lobby,” said Stapleton.

“And maybe their grandchildren coming in and saying ‘my god, that was my grandmother.

"'What a gal she was.'"