October 14, 2019

An email appeared in Betty Bird's inbox one afternoon in April 2018 with answers to something she had been searching for for more than 30 years.

It contained a court document that described how Bird's closest childhood friend, Janelle Mercredi, was brutally killed 32 years earlier.

Bird, at her office and unsure how she would react, waited to read it. She wanted to be at home, free to sob or sit silently.

Bird didn't know it at the time, but that email was the beginning of a journey that would eventually take her to a graveyard in Edmonton to say goodbye to the friend she'd wondered about for decades.

An instant bond

Bird and Mercredi met as 15-year-olds in Fort Smith, a small town along the southeast edge of the Northwest Territories. Mercredi was the new kid in town and the two formed an instant friendship.

"She had attitude, and so did I, and so we kind of complemented each other," recalled Bird with a laugh.

"We got in a lot of trouble, because we were always talking, or skipping [school], or smoking in the girls' bathroom."

Bird describes Mercredi as a "girly-girl," who liked to do her makeup and hair, and dreamed of one day being a model. The Métis teen was even named queen at the town's winter carnival, Wood Buffalo Frolics.

Despite their close friendship, Bird says they never talked about their pasts. All Bird knew was that Mercredi was from Yellowknife, and was living at Trailcross, a facility in Fort Smith for youth who'd been in trouble with the law or were in government care.

Bird was silently struggling as a victim of sexual abuse, and drew strength from their friendship.

"I looked at myself as less than, and I think that Janelle felt the same way. And I think that's what brought us together as friends."

But only a year after they met, Mercredi left Fort Smith for good.

CBC's Rachel Zelniker tells Betty and Janelle's story in this documentary for The Doc Project.

Two years later, when Bird was 18, she learned Mercredi had moved to Edmonton to pursue a modelling career. But she was struggling and working as a prostitute.

Determined to reconnect, Bird travelled to Edmonton.

"When I found her, somebody had tried to strangle her, so she had a scar around her neck, and she had a glass eye," Bird said.

"She didn't want to talk to me and she didn't want me to talk to her. She kept saying over and over, 'The person that you knew, I'm not,' and we ended up parting ways."

Bird returned to Fort Smith and tried to leave their friendship behind.

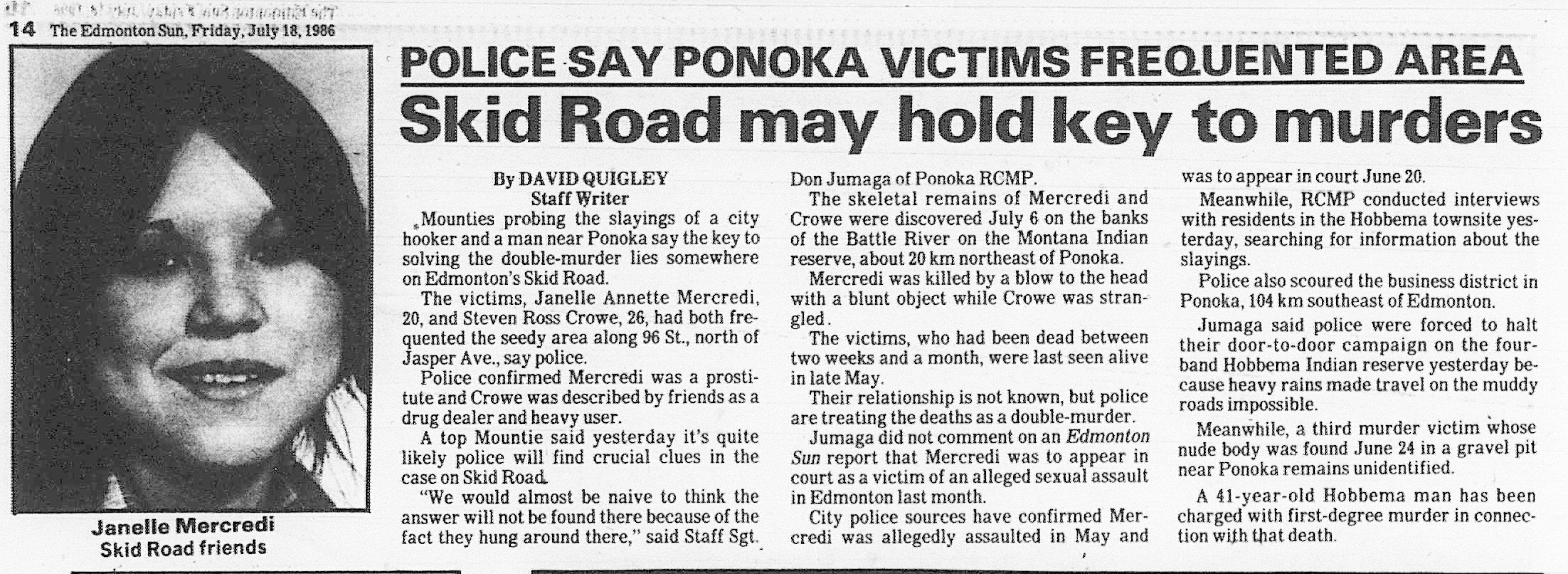

Just two years later, she received some sombre news: Mercredi had been killed at age 20.

Devastated and angry, Bird vowed to make a change in her life and honour her friend going forward.

"After she died, I decided to go back to school, because I wanted to stop what happened to Janelle from happening to somebody else."

A turning point

Bird enrolled in social work at Aurora College, and now, at 53, has been working in victim services for the past 27 years.

As the years went by, she continued to think about Mercredi. Now living in Fort Simpson, every so often, a case or victim she worked with would bring back an old memory.

Bird desperately wanted to learn more about what happened to her friend, but wasn't sure where to start.

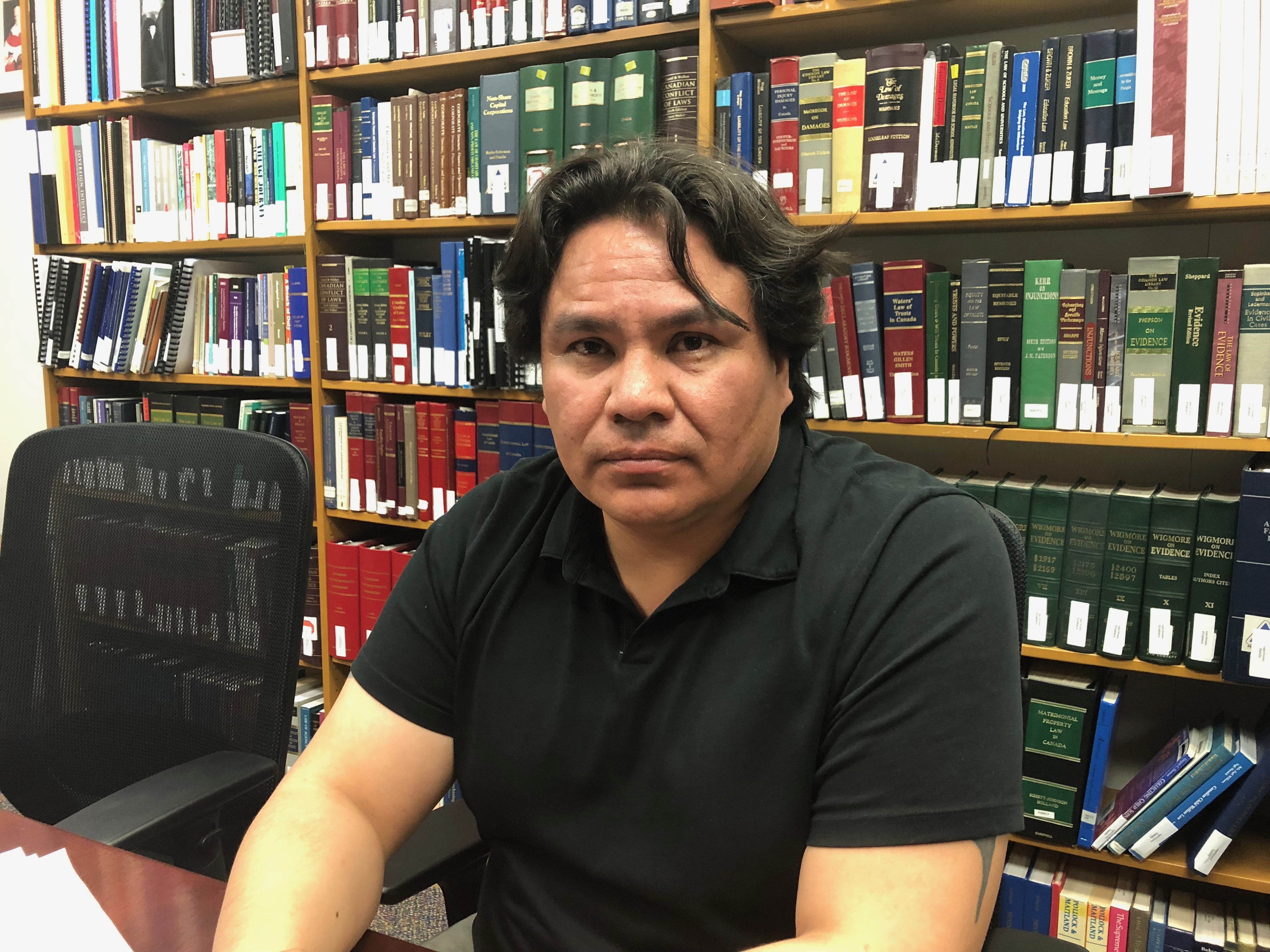

Then, in 2018, she met Curtis Mandeville, a family information liaison co-ordinator with the N.W.T. Department of Justice.

He was visiting Fort Simpson to educate community members about his role as a conduit for the families of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls looking for information, and was sympathetic to her cause.

"Betty relayed a story to me about her friend going back to the 1980s," recalled Mandeville.

"I am from the North, and I know that with a lot of people dealing with missing or murdered loved ones, it's extremely tough. And many of them — if not all — have questions, and it's really hard to find those answers on your own."

Mercredi is one of hundreds of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada. According to Statistics Canada, Indigenous women are three times more likely to be victims of violence than non-Indigenous women.

Her family testified before the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls last year in Yellowknife.

Mandeville offered to help Bird, and spent the next few months trying to dig up public information.

That April, he came across a court document — the one that landed in Bird's inbox. He told her to prepare for something "pretty brutal."

According to an Alberta court document, on the night of June 4, 1986, Mercredi was at a house party in Edmonton where considerable drinking and a number of assaults took place.

Mercredi was brutally beaten by several people.

Her body was wrapped in a carpet and dumped in a gravel pit about 60 kilometres south of Edmonton. At least one person was convicted of second-degree murder in her killing.

"My friend died a pretty hard death," said Bird, choking back tears.

Mandeville promised Bird he would keep working to find Mercredi's grave. This past June, he confirmed that Mercredi was buried at Edmonton's Holy Cross Cemetery.

"I kind of felt chills … It was finally a sense of relief," said Mandeville.

He immediately called Bird to tell her the news.

"I was very, very grateful," said Bird. "He had no idea the gift he had given me."

More than a number

Mercredi's aunt, Ruth, describes her niece's murder as a "tragedy" that rocked the family. She paints a picture of a young woman who was "very loving," but faced a number of challenges in her short life.

She said her niece struggled with the law and an unstable home life, partly stemming from the effects of intergenerational trauma and Canada's colonial legacy.

Ruth Mercredi said the family is incredibly grateful to Bird, who they've never met, and that she's touched by Bird's continued connection to Janelle.

She said she feels honoured her niece influenced someone's life in such a significant way, and that her legacy lives on through Bird's work and memories.

Thirty-five years after Bird made that initial trip to Edmonton to look for her friend, she travelled back to the city this summer — this time to say a final goodbye.

Carrying a dozen roses dyed blue and black, Mercredi's favourite colours, she walked through the rows of graves.

When she reached Mercredi's plot, Bird wasn't prepared for what she found: a patch of grass with no headstone or plaque to mark it.

Tearfully, Bird laid down her flowers, lamenting how her friend's life had ended.

"I know they have her name in the office, but for all intents and purposes, she’s just a number right now."

Sitting in the graveyard, Bird also wished her friend could have received the help she needed, when she needed it.

"I was sitting here, telling her she made me a better person," she said. "I work with people who have experienced a tremendous amount of tragedy, and I wish I could have been that person for her back then."

Bird's journey to honour her friend isn't over. She plans to come back to Edmonton once more to place a headstone on Mercredi's grave.

"She's not going to be a number anymore."