Under the cover of darkness, Canadian surgeon John McCrae stood in a Belgian field presiding over the burial of his close friend Lt. Alexis Helmer. It was May 2, 1915.

Earlier that day, Helmer, a 22-year-old from Ottawa, had been killed by an eight-inch German shell launched from the other side of the Yser Canal. He was blown to bits, and what could be found of him was collected and placed in the shape of a body on an army blanket.

The burial had to wait until night to avoid giving the Germans a target. Remarkably, the last words entered into Helmer's diary had been: "It has quieted a little and I shall try to get a good sleep." From memory, McCrae recited some passages from the Order for Burial of the Dead. Helmer was buried and a wooden cross marked the spot in an area of Belgium known as Flanders.

Ten days before, the Germans had launched the first mass gas attack of the First World War, unleashing about 150 tonnes of chlorine gas, which resulted in a massive green-yellow cloud six kilometres long that swept through two French colonial divisions. As soldiers suffocated and fled, there emerged an opening on the front line that Canadian and British troops rushed to fill to prevent the Germans from advancing. Two days later, on April 24, the Germans carried out another gas attack, this time directly on Canadian troops.

McCrae, in a letter to his mother, described the days that followed. "The general impression in my mind is of a nightmare," he wrote. "We have been in the most bitter of fights. For seventeen days and seventeen nights none of us have had our clothes off, nor our boots even, except occasionally. In all that time while I was awake, gunfire and rifle fire never ceased for sixty seconds."

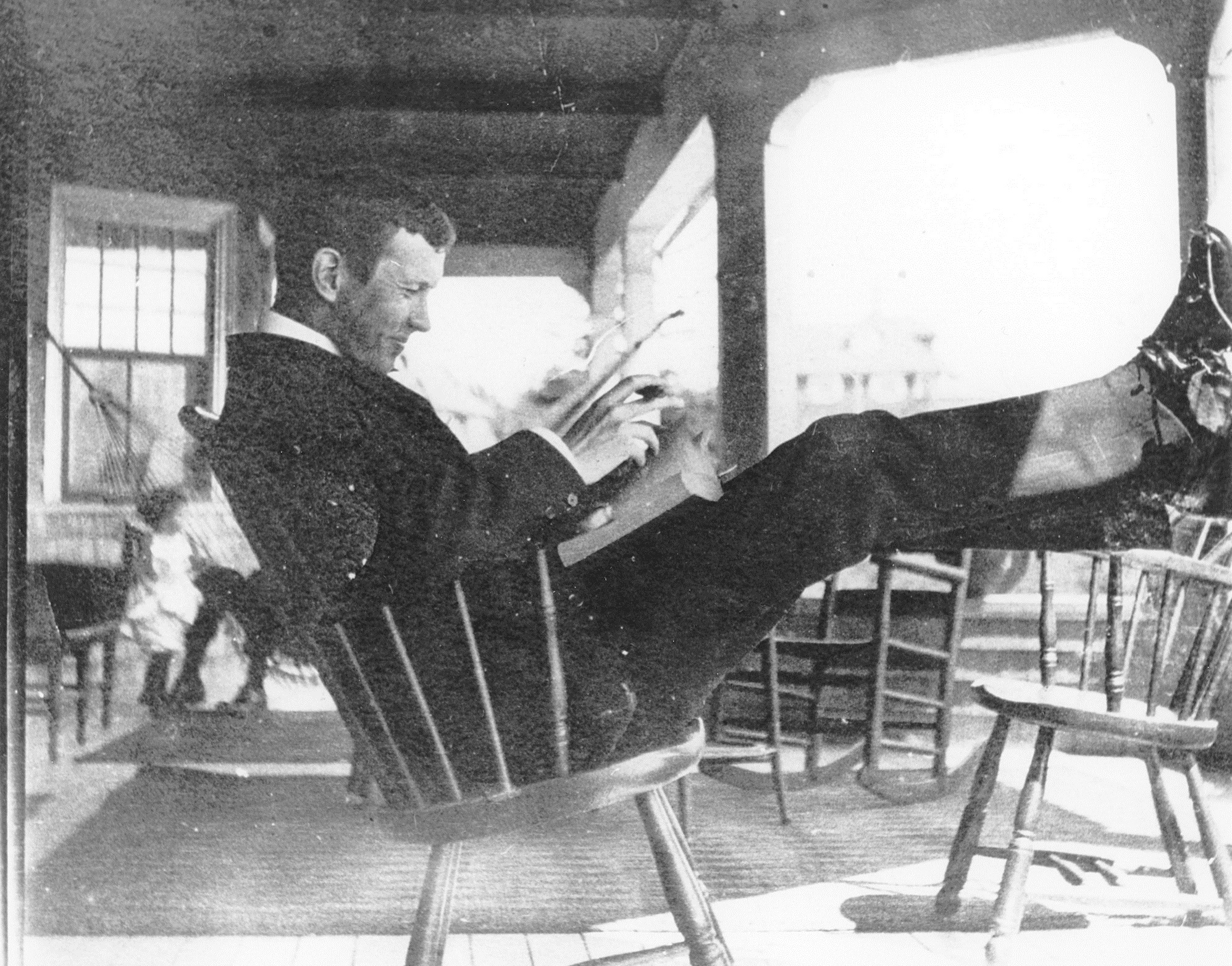

He treated injured soldiers inside dingy, tiny, poorly lit dressing stations, earthen bunkers dug into the side of a hill. Against this backdrop and out of grief over the death of his friend, McCrae, 42, wrote a poem in about 20 minutes as he took a break between surgeries. In one account, he was spotted sitting at the back of an ambulance as he sketched out the poem, looking toward Helmer's grave and the poppies that grew easily in the war-torn landscape.

The setting helped inspire the vivid imagery of In Flanders Fields.

"It was a very literal and emotional experience for him to write this poem," says Ken Irvine, a museum co-ordinator in Guelph, Ont., who has studied McCrae's life.

Within less than a year, In Flanders Fields would become internationally famous and was even used to sell $400 million of Canadian war bonds in 1917.

More than 103 years after its writing, the poem is an integral part of Remembrance Day ceremonies. Around 66,000 Canadians and Newfoundlanders were killed in the First World War, while more than 172,000 out of the 650,000 men and women who served were wounded, according to Veterans Affairs Canada.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved, and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

McCrae himself wouldn't live to see the end of the war. In the 100 years since his death, his legacy has often been boiled down to that of the Canadian First World War medic who wrote In Flanders Fields after the death of a friend.

"It's sort of unfortunate that people don't know more about the man," says Irvine. "They know the poem and they may have heard the name John McCrae attached to it, but they don't know anything about this incredible man and great Canadian who wrote this poem.

"He had such a remarkable life."

So, who was John McCrae?

McCrae was born in Guelph, Ont., in 1872. One of three children, he got from his mother his love of literature and strong Presbyterian faith — her father was a lay preacher. McCrae was bright and could recite part of the catechism at age three.

He loved adventure and grew up near a river in Guelph, where he would have swum and canoed, says Irvine. He was also part of a hiking club.

His interest in the military came through his father, who founded the local militia. McCrae joined the cadets and was once given a gold medal for being the best-trained cadet in Ontario. He also served in the militia, which was commanded by his father.

McCrae went to the University of Toronto and was the first student from his high school to get a full scholarship. While there, he played on the varsity rugby team, sang in the glee club and got his bachelor of arts degree in 1894. For the next four years, he studied medicine at the university, but also made time to write 16 poems and several short stories that were published in magazines, all while finishing at the top of his class.

After graduating, McCrae worked as the resident house officer at the Toronto General Hospital, and in 1899 he interned at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

The South African War — also known as the Boer War — broke out in October 1899. The war stemmed from a conflict between the British Army and Dutch settlers, known as Boers, the Dutch word for farmer. McCrae wanted to serve. "He was a man of duty and he felt it was his duty as a single, young man to help out Britain and the imperial army," says Irvine.

McCrae unsuccessfully tried to sign up with the first Canadian contingent that went overseas and was devastated by not being able to go, says Irvine. When a second contingent was sent, McCrae was thrilled to be a part of it and set sail for Africa in December 1899.

To do so, McCrae had to postpone a pathology fellowship he had accepted at McGill University in Montreal.

While serving in South Africa for a year, McCrae was involved in three major engagements and came close to death once, although not in battle. He was fording a stream swollen from recent downpours when his horse spooked, threw him off, fell on top of him and pinned him underwater. McCrae would have drowned, but the men of his artillery battery pulled the horse off and saved him.

When McCrae returned to Canada, he resumed his pathology fellowship and began his impressive career in medicine, which included working at hospitals in Montreal and lecturing at the University of Vermont Medical College in Burlington, Vt., and at McGill. McCrae also continued to publish poetry, write articles for medical journals and even co-authored a book on pathology.

It was at McGill that McCrae likely first crossed paths with Alexis Helmer, a student at the university whose later death on the battlefield inspired In Flanders Fields.

When Great Britain declared war on Germany on Aug. 4, 1914, McCrae was nearing 42 and just happened to be on his way to England for a holiday. Given his age, it would have been perfectly acceptable for McCrae not to enlist, but he didn't see it that way. "It is a terrible state of affairs, and I am going because I think every bachelor, especially if he has experience of war, ought to go," he wrote in a letter to a friend. "I am really rather afraid, but more afraid to stay at home with my conscience."

Since there was a greater need for medical personnel than soldiers, and his artillery experience was out of date, McCrae served as a doctor. It's not what he wanted. He wrote to his mother that it was fighting men that were needed, as medical personnel weren't going to win the war.

McCrae was given the title of brigade-surgeon and had the rank of major. He was second-in-command of the 1st Canadian Field Artillery Brigade, the same unit Helmer served in.

Born in 1892 in Ottawa, Helmer grew up in Hull, Que., where he was a quiet, athletic and good student. He enlisted in 1914 and was popular with his fellow troops, who called him Prince.

Sandra Campbell, a semi-retired literature professor from Carleton University who has researched Helmer's life, suspects he got the nickname because during the First World War, the Czar of Russia's son — Alexei Nikolaevich — received a lot of press and the two had a similar first name.

"He was a very good soldier with a messy kit, and before he got to the Second Battle of Ypres, which is where he died at the Yser Canal, he also had some experience with poison gas because he was the forward observation officer one night when gas was used," says Campbell. "In fact, the gas did affect him to some degree, but it didn't kill him."

After the Second Battle of Ypres, McCrae was worn down and exhausted. He was pulled from the artillery brigade and posted in June to the Number 3 Canadian General Hospital in Dannes-Camiers, on the coast in northern France. McCrae was in charge of medicine at the tent hospital, which placed him well back from the front lines.

McCrae first tried to have In Flanders Fields published in a publication called The Spectator, but it was rejected. On Dec. 8, 1915, In Flanders Fields was published in Punch, an English satirical magazine, where it appeared without a byline.

"It was just tiny little filler at the bottom of a page of Punch and it just exploded, you know, it just became wildly popular and it was printed everywhere," says John Prescott, the author of In Flanders Fields: The Story of John McCrae. "Eventually, he had his name attached to it somehow. His name was usually misspelled, nobody quite knew how to spell McCrae."

The poem resonated with the public and soldiers, who were known to recite it in the trenches. It was the second-last poem McCrae ever wrote.

As a tent hospital, the Number 3 Canadian General Hospital was subject to the elements. In October, "severe storms led to flooding of the wards, tearing of the canvas, and pulling up of the tents," says Prescott's book. In November, colder weather — frost, rain and icy winds — led to the shutdown of the hospital. A search began for a new hospital location and an old Jesuit college in Boulogne, about 25 kilometres north of Dannes-Camiers, was selected.

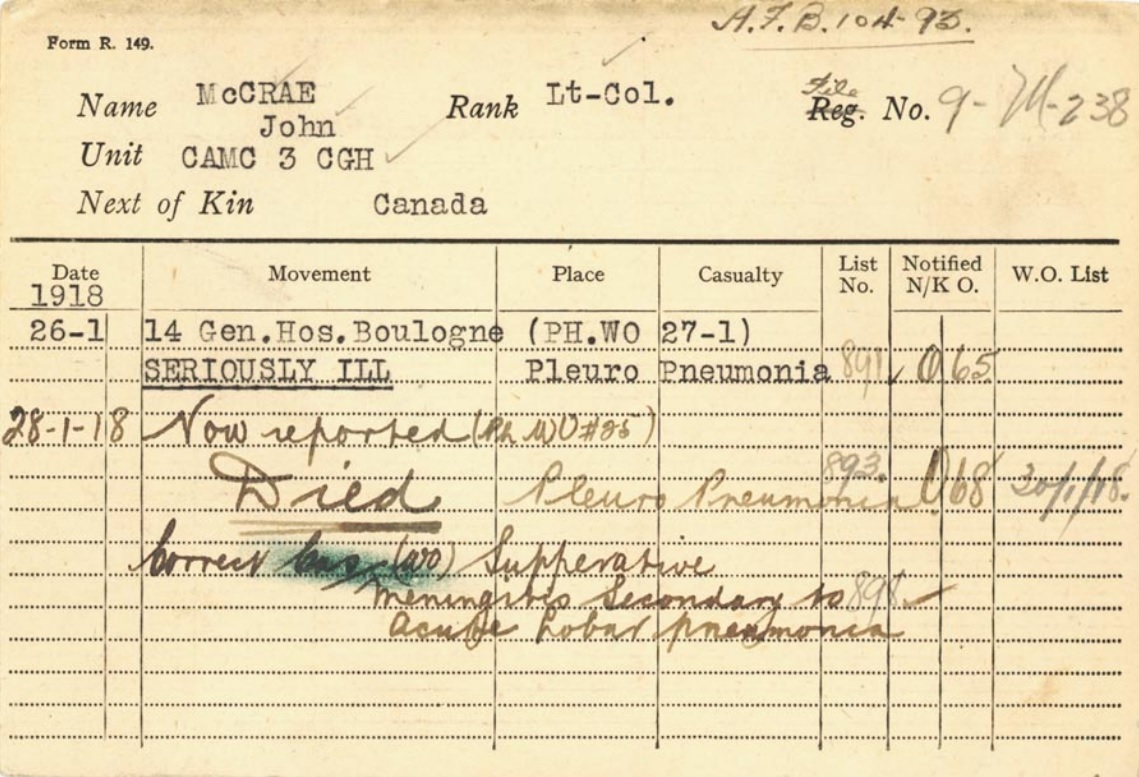

By early 1918, a friend described McCrae as "silent, asthmatic, moody," according to Prescott's book. On Jan. 24, he was appointed consulting physician to the First British Army, making him the first Canadian to receive that distinction. McCrae learned of the honour while ill in bed with pneumonia. His health worsened and he slipped into a coma. On Jan. 28, the 45-year-old died of pneumonia and meningitis.

In an obituary published in the British Medical Journal, a friend wrote that McCrae "felt the war intensely, and it had changed him. Loyal and straightforward as ever, he was no longer the cheery, light-hearted companion full of good sayings ... Now, the war was with him night and day." This was a far cry from the McCrae who was considered the life of any party and always had an entertaining story to tell.

It was likely that McCrae was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Campbell says one of his ways to keep the pain at bay was to go on long rides on his horse, Bonfire. McCrae's dog, Bonneau, also accompanied the pair on these treks.

While McCrae should probably have been sent back to Canada to heal, he would never have allowed that. "He would have to be ordered by somebody very senior to go back and he would have fought it tooth and nail because he was a fighter," says Prescott.

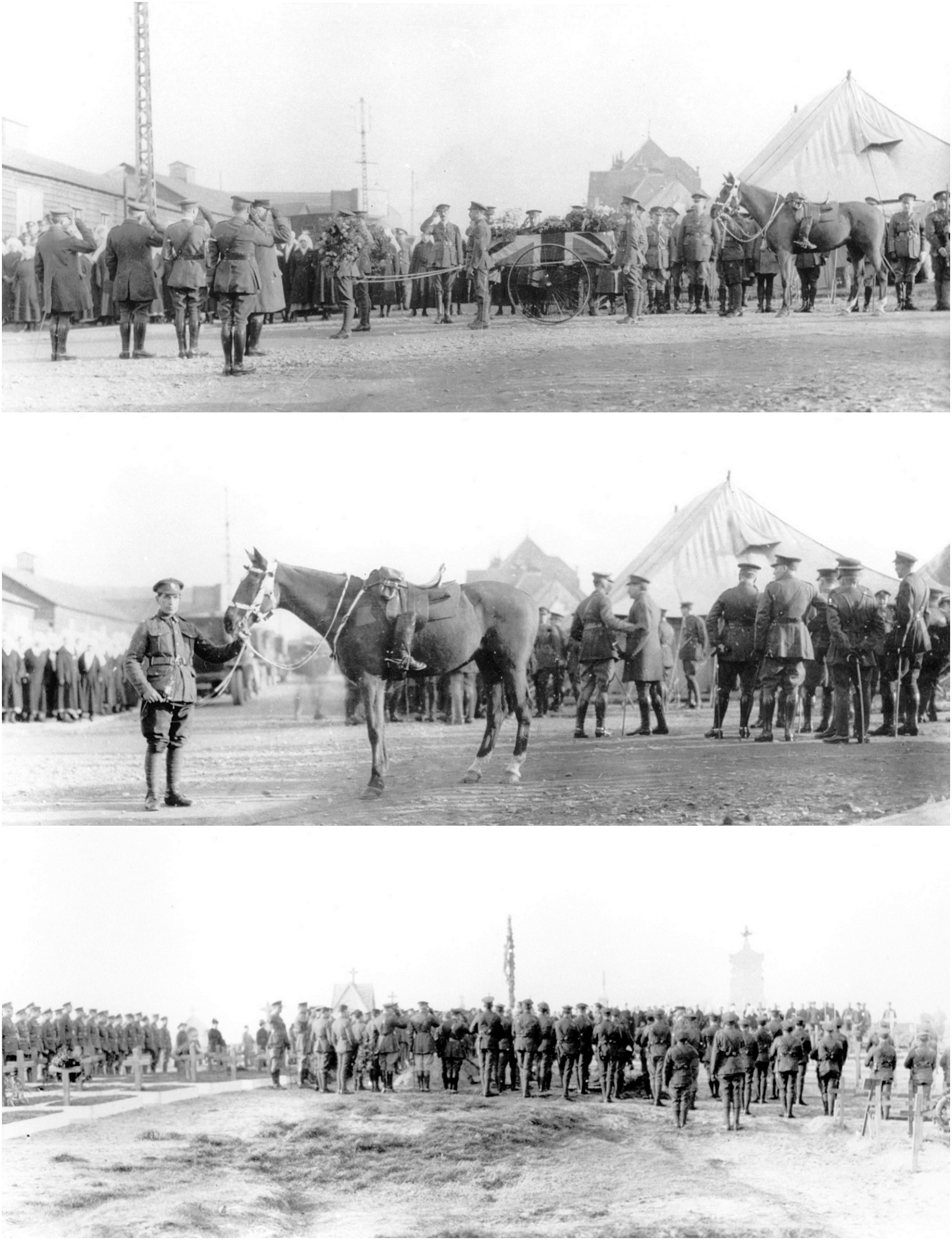

McCrae was buried with full military honours in Wimereux, France, just north of Boulogne, on a spring-like day on Jan. 30. The service was well-attended by soldiers and nurses, and included dignitaries such as Gen. Arthur Currie, the commander of the Canadian Corps. "The funeral … was by far the largest and most impressive I have seen here; indeed it was the most impressive military funeral I have seen anywhere," wrote Col. J.M. Elder.

In Flanders Fields wasn't intended as a poem of remembrance, according to Tim Cook, the First World War historian at the Canadian War Museum. "It is a poem to keep fighting and that I think is often lost on people."

The poem is a voice from the grave — "We are the dead" — calling for the Allies to continue fighting — "Take up our quarrel with the foe." If the fight isn't carried on, the fallen soldiers won't sleep, yet the poppies will continue to grow in Flanders Fields.

"It was created on the battlefield," says Cook. McCrae "wrote it while suffering from lethal, chlorine gas poisoning. He watched his friends and comrades being torn apart in battle. He wrote about the battle of Second Ypres of being two weeks of hell and he really thought he was going to be killed there, and so that's the context of the poem — the dead soldiers, his comrades, telling others to keep up the fight."

In Wimereux today, not even a few hundred metres from where McCrae is buried, a street is named after him, even if the spelling is incorrect — Rue Mac Crae.

The dressing stations where he worked near the front were fortified with concrete after the war to ensure their survival. The site is now home to the present-day Essex Farm Cemetery, and more than 1,000 serviceman from the First World War are now buried or commemorated there.

Where Helmer was buried is unknown, as another 3½ years of war continued to destroy the Belgian landscape where he was entombed.

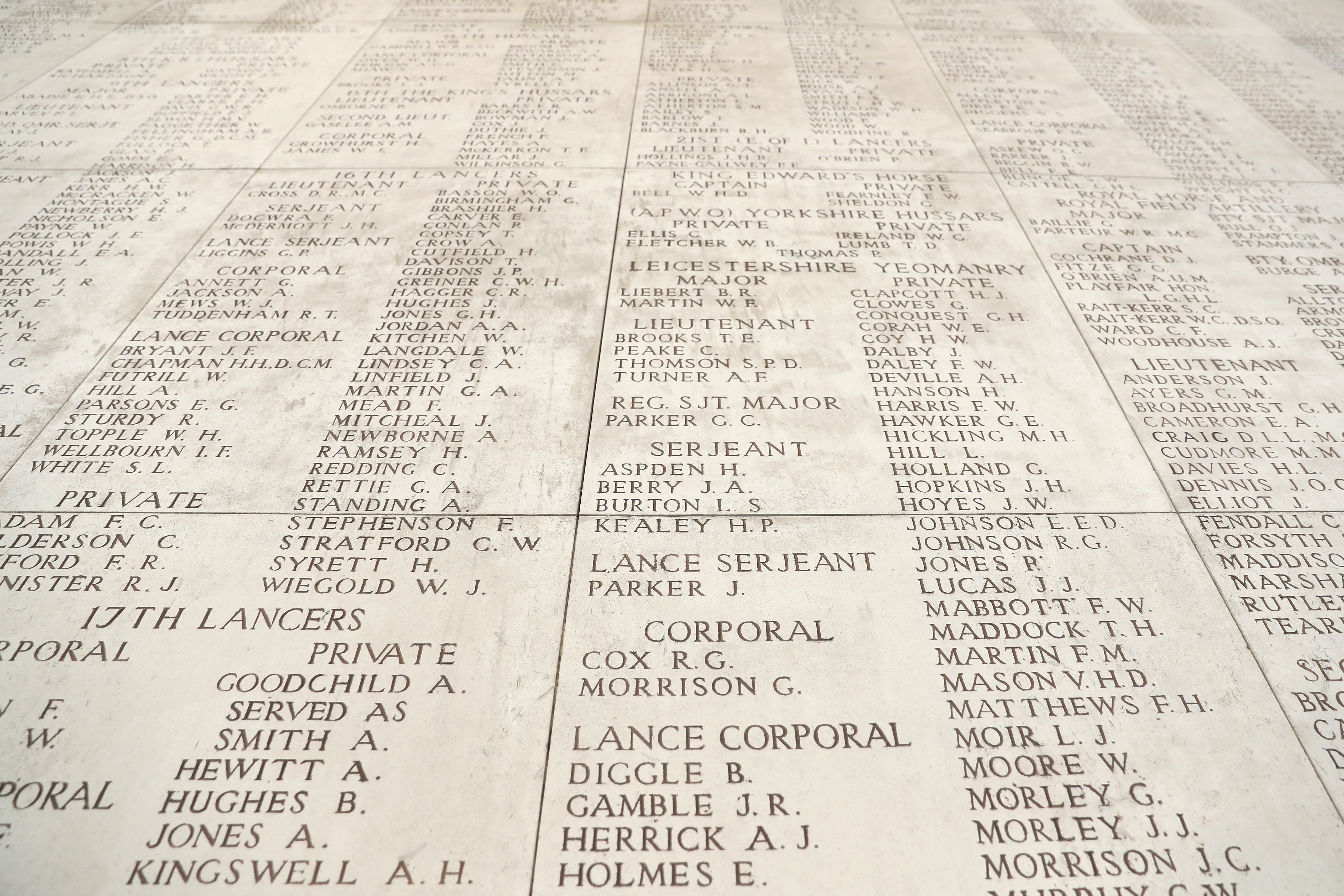

His name is today listed at Menin Gate in Ypres, a memorial bearing the names of the more than 54,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers killed in the First World War who have no known grave. A ceremony has been held there nightly since 1928 to honour the dead soldiers, except when the Nazis occupied the country during the Second World War.

With McCrae's death, Canada lost a renaissance man — an author, pathologist, poet, soldier, storyteller and surgeon.

Even if he had survived the war, the McCrae that would have returned to Canada wouldn't have been the one that left the country four years prior, says Linda Granfield, the author of In Flanders Fields: The Story of the Poem by John McCrae. "People sometimes like to think, 'Oh, imagine, he would have written more poetry when he came back and he would have been a doctor, he would have been back teaching at McGill.' But he would have been too changed … dealing with that amount of death and dying. I don't see how he could have remained unchanged," she says.

The First World War left behind a trail of destruction such as the world had never seen. Thirty countries took part and at least 10 million men were killed out of the 65 million who fought in it, while 29 million were wounded, captured or went missing, according to Veterans Affairs Canada.

The war ended when an armistice was reached on Nov. 11, 1918.

In the 103 years since In Flanders Fields has been published, the words haven't changed, but its meaning has. "I think that's the power of the poem," says Cook. "The torch is no longer being passed to keep up the fight. It is now a torch of remembrance. It is the dead who now command the living in the post-war years that they must remember the fallen. And I think that's interesting that the words don't change, the poem remains the same, but its meaning has changed and it continues to reverberate."